Manchuria

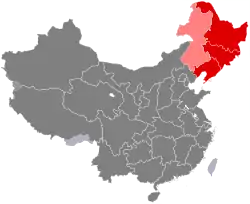

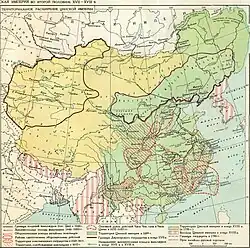

Manchuria refers to a region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China or, historically, those areas combined with parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manchuria). Its definition may refer to varying geographical extents as following: the Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning but broadly also including the eastern Inner Mongolian prefectures of Hulunbuir, Hinggan, Tongliao, and Chifeng, collectively known as Northeast China. Historically included homeland of the Jurchens and later their descendants Manchus, which was controlled in whole by Qing China prior to the Amur Annexation in 1858–1860, when parts of the historical region were ceded to the Russian Empire. The two areas involved are Priamurye between the Amur River and the Stanovoy Range to the north, and Primorskaya which runs down the Pacific coast from the Amur mouth to the Korean border, sometimes including the island of Sakhalin- collectively known as Outer Manchuria or Russian Manchuria.

| Manchuria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

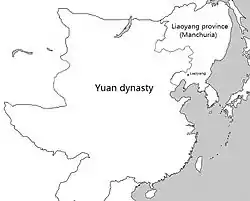

The modern sense of Manchuria refers to the red and pink area (Northeast China and eastern Inner Mongolia) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

A broader definition. Manchuria lies in Northeast China, coloured in red; eastern Inner Mongolia to the west, in slightly lighter red; and Outer Manchuria to the north-east, in pink. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 满洲 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 滿洲 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 만주 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 滿洲 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 満州 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | まんしゅう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡩᡝᡵᡤᡳ ᡳᠯᠠᠨ ᡤᠣᠯᠣ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Dergi Ilan Golo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Russian | Маньчжурия | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Man'chzhuriya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

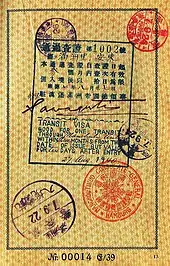

The name Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endonym "Manchu") of Japanese origin. The history of "Manchuria" (Manzhou) as a toponym in China is disputed with some scholars believing it was never used while others believe it was by the late 19th century. The area was historically referred to by various names in the Qing dynasty such as Guandong (East of the Pass) or the Three Provinces referring to Fengtian, Heilongjiang, and Jilin. Manchuria as a geographical term was first used in the 18th or 19th centuries by the Japanese before spreading to Europe. The term was promoted by the Japanese Empire in support for the existence of its puppet state, Manchukuo. Although the toponym is still used, some scholars treat the term with caution or avoid it altogether due to its association with Japanese colonialism. The term is deprecated in China due to its association with Japanese imperialism and ethnic connotations. As a result, areas once considered part of Manchuria are simply referred to as the Northeast.[1] The Three Provinces and the Northeast were also in concurrent use among the Japanese along with Manchuria until the Mukden Incident of 1931.[2]

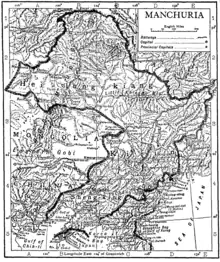

Boundaries

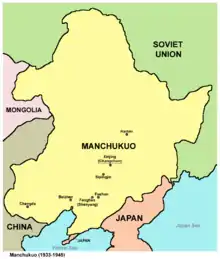

Manchuria is now most often associated with the three Chinese provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning.[3]: 3 [5] The former Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo further included the prefectures of Chengde (now in Hebei), and Hulunbuir, Hinggan, Tongliao, and Chifeng (now in Inner Mongolia). The region of the Qing dynasty referenced as Manchuria originally further included Primorskiy Kray, the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, the southern parts of Amur Oblast and Khabarovskiy Kray, and a corner of Zabaykalʼskiy Kray. These districts were acknowledged as Qing territory by the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk but ceded to the Russian Empire due to the Amur Annexation in the unequal 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Convention of Beijing (the People's Republic of China indirectly questioned the legitimacy of these treaties in the 1960s, but has more recently signed agreements such as the 2001 Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship, which affirm the current status quo;[6] a minor exchange nonetheless occurred in 2004 at the confluence of the Amur and Ussuri rivers).[7] Various senses of Greater Manchuria sometimes further include Sakhalin Island, which despite its lack of mention in treaties was shown as Qing territory on period Chinese, Japanese, Russian, and French maps of the area.

Map of the three provinces of Northeast China (1911)[8]

Map of the three provinces of Northeast China (1911)[8] Map of Manchukuo and its rail network, c. 1945

Map of Manchukuo and its rail network, c. 1945 Drainage basin of the Amur River, also showing the island of Sakhalin in the east

Drainage basin of the Amur River, also showing the island of Sakhalin in the east

Names

Origins

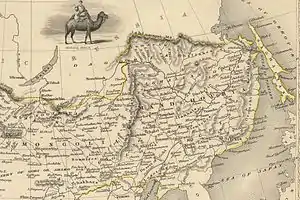

The geographical term "Manchuria" was first used in the 18th or 19th century by the Japanese. "Manchuria" – variations of which arrived in European languages through Dutch – is a calque of Latin of the Japanese placename Manshū (満州, "Region of the Manchus"), which dates from the 18th century.[10]

According to the American researcher Mark C. Elliott, the term Manshū first appeared as a placename in Katsuragawa Hoshū's 1794 work Hokusa Bunryaku in two maps, "Ashia zenzu" and "Chikyū hankyū sōzu", which were also created by Katsuragawa.[11] According to Junko Miyawaki-Okada, Japanese geographer Takahashi Kageyasu was the first to use the term Manshū as a toponym in 1809 in the Nippon Henkai Ryakuzu, and it was from that work that Westerners adopted the name.[12][13] By the 1830s, various Indo-European forms of Manshū could be found.[1] However according to Li Narangoa, the term was introduced to Japan in the 18th century through European maps following Jesuit conventions.[2]

Manshū then increasingly appeared on maps by Japanese cartographers such as Kondi Jūzō, Takahashi Kageyasu, Baba Sadayoshi, and Yamada Ren. Their maps were brought to Europe by Philipp Franz von Siebold.[1] According to Japanese scholar Nakami Tatsuo, Siebold was the one who brought the usage of the term Manchuria to Europeans after borrowing it from the Japanese, who were the first to use it in a geographic manner in the 18th century.[10]

China

The history of the use of "Manchuria" as a toponym in China is uncertain. According to one stream of thought, it was not used by the Manchus or the Chinese.[10][14] The name Manchu was given to the Jurchen people by Hong Taiji in 1635 as a new name for their ethnic group. However neither the name Manchu or the Chinese rendering of Manshū as Manzhou ever acquired geographical connotations, while in Japanese, both Manchuria and Manchu are rendered as Manshū. According to Nakami Tatsuo, Manzhou was used to refer to Manchu people or one of their states rather than a region: "Originally, Manzhou was the name of the Manchu people or of their state; it was not the name of a region. In fact, neither Manchus nor Han Chinese have ever called China's Northeast 'Manzhou'."[2][1] Even advocates of an independent Manchuria such as Inaba Iwakichi acknowledged this.[1][14] In 1912, British diplomat and sinologist Herbert Giles stated in China and the Manchus that "'Manchuria' is unknown to the Chinese or to the Manchus themselves as a geographical expression".[10] According to Owen Latimore, during his travels in China during the late 1920s, he found "no single Chinese name for Manchuria as a unit".[15][16] Historical geographer Philippe Forêt concurred, noting that there is no word for Manchuria in either Chinese or Manchu languages.[17]

Another perspective delineated by scholars such as Mark C. Elliott and Li Narangoa argues that Manchu consciousness of their homeland as a unique place contributed to the creation of Manchuria as a distinct geographical entity, and that "Manchuria" (Manzhou) was used as a toponym by the Chinese. According to Elliott, the Manchu imperial lineage believed that their original homeland was the Changbai Mountains. The Qing court endeavored to create a regional identity focused on the Changbai Mountains, which gradually became a symbol of Manchu identity. However it is uncertain whether that notion was shared among ordinary Manchus, and there is evidence that part of that effort was to combat widespread acculturation among Manchus, resulting in the loss of their language. As part of this effort, Jesuits were commissioned to create maps that enhanced Manchu conceptualization of their homeland, which Elliot believes to have been the original impetus to label the region as Manchuria in European and Japanese maps. In 1877, Manzhou was used as a toponym in an essay by Gong Chai, a scholar from Ningbo. The description of Manzhou located it to the northeast of Beijing and identified it as the birthplace of the dynasty. Manzhou was used as a place name again 20 years later by Qing officials. Manzhou began to appear on Chinese maps in the first decade of the 1900s. Maps that used Manzhou were in the minority during the early Republican period but the name remained in common use among the Chinese Communist Party into the 1930s. Names for the region were relatively fluid before the Mukden Incident of 1931, after which alternative names in Japanese were discarded for Manshū, and Dongbei (Northeast) and Dongsansheng (Three Eastern Provinces) became the orthodox names for the Chinese. By the 1950s, Manzhou had virtually disappeared as a toponym although some still used it out of habit.[1][2]

Japan

The term Manchuria has been described as "controversial" or "troublesome" by several scholars including Mark C. Elliott, Norman Smith, and Mariko Asano Tamanoi. The historian Norman Smith wrote that "The term 'Manchuria' is controversial" based on reasons outlined by Mariko Asano Tamanoi in the "Introduction" of Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire (2005).[18] According to Tamanoi, "'Manchuria' is a product of Japanese imperialism, and to call the area Manzhou is to accept uncritically a Japanese colonial legacy." Japan used the name "Manchuria" to convey the idea of a contested region distinct from China while China insisted on its ownership of the region by rejecting the name "Manchuria". Japanese colonists who returned to Japan from Manchukuo in the post-war period used terms such as Manshu (Manchuria), Man-mō (Manchuria-Mongolia), and Mō-man (Mongolia-Manchuria) almost interchangeably.[16][2] Hyphenated terms such as Man-sēn (Manchuria and Korea) and Man-mō (Manchuria-Mongolia) emerged in Japanese media and traveler writings during the first three decades of the 20th century, implying that these regions were extensions of each other.[19] Tamanoi notes that the name "Manchuria" cannot be found on Chinese maps and acknowledged that she "should use the term in quotation marks" even though she did not.[15]

Historian Bill Sewell denies that Manchuria is "a genuine geographic term", claiming the Japanese never viewed Manchuria as a discrete entity and it was Europeans who first started using the name Manchuria to refer to the location.[20] Others such as Forêt described Manchuria as a solely geographical term without indicating a political connection and used it in that capacity despite acknowledging its imperialistic overtones.[17] The historian Gavan McCormack agreed with Robert H. G. Lee's statement that "The term Manchuria or Man-chou is a modern creation used mainly by westerners and Japanese", with McCormack writing that the term Manchuria is imperialistic in nature and has no "precise meaning" since the Japanese deliberately promoted the use of "Manchuria" as a geographic name to promote its separation from China at the time they were setting up their puppet state of Manchukuo.[21] In the 1920s, Japanese media still presented Manchuria as part of China, albeit as a distinct region, and sometimes called it the "Garden of China". However in 1932, the puppet state of Manchukuo was founded covering not only the northeastern three provinces but also parts of eastern Inner Mongolia.[19] In 1933, the Bureau of Information and the Publicity Department of Foreign Affairs of the Manchukuo Government published a Handbook of Information of Manchukuo stating that Manchuria did not belong to China, had its own history and traditions, and was the home of the Manchus and Mongols.[22] Elliot notes that one scholar considered the use of "Manchuria" as not only inaccurate but giving approval to Japanese colonialism.[1]

Three Provinces

During the Qing dynasty, the region was known as the "three eastern provinces" (東三省; 东三省; Dōngsānshěng; Manchu ᡩᡝᡵᡤᡳ

ᡳᠯᠠᠨ

ᡤᠣᠯᠣ, Dergi Ilan Golo), which referred to Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Fengtian since 1683 when Jilin and Heilongjiang were separated.[24] However Jilin and Heilongjiang did not receive the full function of provinces until 1907.[24][25] The Japanese also used the name "Three Eastern Provinces" (Tōsanshō) during the 1920s and 1930s along with Manshū. However after the Manchurian Incident of 1931, Tōsanshō was completely replaced by Manshū in Japanese usage while the Three Provinces and Northeast became the orthodox name for the same region in Chinese usage.[2]

Guandong

Manchuria has been referred to as Guandong (關東; 关东; Guāndōng), which literally means "east of the pass", and similarly Guanwai (關外; 关外; Guānwài; 'outside the pass'), a reference to Shanhai Pass in Qinhuangdao in today's Hebei, at the eastern end of the Great Wall of China. This usage is seen in the expression Chuǎng Guāndōng (literally "Rushing into Guandong") referring to the mass migration of Han Chinese to Manchuria in the 19th and 20th centuries. The name Guandong later came to be used more narrowly for the area of the Kwantung Leased Territory on the Liaodong Peninsula. It is not to be confused with the southern province of Guangdong.[26]

Northeast Region

_(14763639145).jpg.webp)

The term "Manchuria" is deprecated among people of the People's Republic of China (PRC) due to its association with Japanese imperialism, the puppet state of Manchukuo of the Empire of Japan, and Manchurian nationalism. Official state documents use the term Northeast Region (东北; Dōngběi) to describe the region. Northeast China is predominantly occupied by Han Chinese due to internal Chinese migrations[27] and Sinicization of the Manchus, especially during the Qing dynasty. It is considered the original homeland of several historical groups besides the Manchus, including the Yemaek[28][29][30] the Xianbei,[31] the Shiwei, and the Khitans. The area is also home to many Mongols and Hui.[32][27]

In present-day Chinese, an inhabitant of the Northeast is a "Northeasterner" (东北人; Dōngběirén). "The Northeast" is a term that expresses the entire region, encompassing its history and various cultures. It is usually restricted to the "Three East Provinces" or "Three Northeast Provinces", excluding northeastern Inner Mongolia. In China, the term Manchuria (traditional Chinese: 滿洲; simplified Chinese: 满洲; pinyin: Mǎnzhōu) is rarely used today, and the term is often negatively associated with the Japanese imperial legacy and the puppet state of Manchukuo.[33][17] The Northeast (Tōhoku) was also used as a name for Manchuria by the Japanese during the 1920s and 1930s.[2]

Geography and climate

Manchuria consists mainly of the northern side of the funnel-shaped North China Craton, a large area of tilled and overlaid Precambrian rocks spanning 100 million hectares (250 million acres). The North China Craton was an independent continent before the Triassic period and is known to have been the northernmost piece of land in the world during the Carboniferous. The Khingan Mountains in the west are a Jurassic[34] mountain range formed by the collision of the North China Craton with the Siberian Craton, which marked the final stage of the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea.

No part of Manchuria was glaciated during the Quaternary, but the surface geology of most of the lower-lying and more fertile parts of Manchuria consists of very deep layers of loess, which have been formed by the wind-borne movement of dust and till particles formed in glaciated parts of the Himalayas, Kunlun Shan and Tien Shan, as well as the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts.[35] Soils are mostly fertile mollisols and fluvents except in the more mountainous parts where they have poorly developed orthents, as well as in the extreme north where permafrost occurs and orthels dominate.[36]

The climate of Manchuria has extreme seasonal contrasts, ranging from humid, almost tropical heat in summer to windy, dry, Arctic cold in winter. This pattern occurs because the position of Manchuria on the boundary between the great Eurasian continental landmass and the huge Pacific Ocean causes complete monsoonal wind reversal.

In summer, when the land heats faster than the ocean, low-pressure forms over Asia and warm, moist south to southeasterly winds bring heavy, thundery rain, yielding annual rainfall ranging from 400 mm (16 in), or less in the west, to over 1,150 mm (45 in) in the Changbai Mountains.[37] Temperatures in summer are very warm to hot, with July average maxima ranging from 31 °C (88 °F) in the south to 24 °C (75 °F) in the extreme north.[38]

In winter, however, the vast Siberian High causes very cold, north-to-northwesterly winds that bring temperatures as low as −5 °C (23 °F) in the extreme south and −30 °C (−22 °F) in the north[39] where the zone of discontinuous permafrost reaches northern Heilongjiang. However, because the winds from Siberia are exceedingly dry, snow falls only on a few days every winter, and it is never heavy. This explains why corresponding latitudes of North America were fully glaciated during glacial periods of the Quaternary while Manchuria, though even colder, always remained too dry to form glaciers[40] – a state of affairs enhanced by stronger westerly winds from the surface of the ice sheet in Europe.

History

| History of Manchuria |

|---|

|

Early history

Manchuria was the homeland of several ethnic groups, including Manchu, Mongols, Koreans, Nanai, Nivkhs, Ulchs, Hui and possibly Turkic peoples and ethnic Han Chinese in southern Manchuria. Various ethnic groups and their respective kingdoms, including the Sushen, Donghu, Xianbei, Wuhuan, Mohe, Khitan and Jurchens, have risen to power in Manchuria. Various Koreanic kingdoms such as Gojoseon (before 108 BCE), Buyeo (2nd century BCE to 494 CE) and Goguryeo (37 BCE to 688 CE) also became established in large parts of this area. The Han dynasty (202 BCE to 9 CE and 25 to 220 CE), the Cao Wei dynasty (220–266), the Western Jin dynasty (266–316), the Tang dynasty (618–690 and 705–907) and some other minor kingdoms of China established control in parts of Manchuria and in some cases tributary relations with peoples in the area.[41] Parts of northwestern Manchuria came under the control of the First Turkic Khaganate of 552–603 and of the Eastern Turkic Khaganate of 581–630. Early Manchuria had a mixed economy of hunting, fishing, livestock, and agriculture.

With the Song dynasty (960-1269) to the south, the Khitan people of Inner Mongolia created the Liao dynasty (916-1125) and conquered Outer Mongolia and Manchuria, going on to control the adjacent part of the Sixteen Prefectures in Northern China as well. The Liao dynasty became the first state to control all of Manchuria.[42]

In the early 12th century the Tungusic Jurchen people, who were Liao's tributaries, overthrew the Liao and formed the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), which went on to control parts of Northern China and Mongolia after a series of successful military campaigns. During the Mongol Yuan dynasty rule of China (1271–1368),[43] Manchuria was administered as Liaoyang province. In 1375 Naghachu, a Mongol official of the Mongolia-based Northern Yuan dynasty of 1368–1635 in Liaoyang province invaded Liaodong, but later surrendered to the Ming dynasty in 1387. In order to protect the northern border areas, the Ming dynasty decided to "pacify" the Jurchens in order to deal with its problems with Yuan remnants along its northern border. The Ming solidified control over Manchuria under the Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424), establishing the Nurgan Regional Military Commission of 1409–1435. Starting in the 1580s, a Jianzhou Jurchen chieftain, Nurhaci (1558–1626), started to unify Jurchen tribes of the region. Over the next several decades, the Jurchen took control of most of Manchuria. In 1616 Nurhaci founded the Later Jin dynasty, which later became known as the Qing dynasty. The Qing defeated the Evenk-Daur federation led by the Evenki chief Bombogor and beheaded Bombogor in 1640, with Qing armies massacring and deporting Evenkis and absorbing the survivors into the Banners.[44]

Chinese cultural and religious influence such as Chinese New Year, the "Chinese god", motifs such as the dragon, spirals, and scrolls, agriculture, husbandry, methods of heating, and material goods such as iron cooking-pots, silk, and cotton spread among the Amur natives including the Udeghes, Ulchis, and Nanais.[45]

In 1644, after peasant rebels sacked the Ming dynasty's capital of Beijing, the Jurchens (now called Manchus) allied with Ming general Wu Sangui and seized control of Beijing, overthrowing the short-lived Shun dynasty (1644–1649) and establishing Qing-dynasty rule (1644–1912) over all of China. The Manchu conquest of China involved the deaths of over 25 million people.[46] The Qing dynasty built the Willow Palisade – a system of ditches and embankments – during the later 17th century to restrict the movement of Han civilians into Jilin and Heilongjiang.[47] Only bannermen, including Chinese bannermen, were allowed to settle in Jilin and Heilongjiang.

After conquering the Ming, the Qing often identified their state as "China" (中國, Zhongguo; "Middle Kingdom"), and referred to it as Dulimbai Gurun ("Middle Kingdom") in Manchu.[48] In the Qing shilu the lands of the Qing state (including Manchuria and present-day Xinjiang, Mongolia, and Tibet) are thus identified as "the Middle Kingdom" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages in roughly two-thirds of the cases, while the term refers to the traditional Chinese provinces populated by the Han in roughly one third of the cases. It was also common to use "China" (Zhongguo, Dulimbai gurun) to refer to the Qing in official documents, international treaties, and foreign affairs. In diplomatic documents, the term "Chinese language" (Dulimbai gurun i bithe) referred to the Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol languages, and the term "Chinese people" (中國人 Zhongguo ren; Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) referred to all Han, Manchus, and Mongol subjects of the Qing. The Qing explicitly stated that the lands in Manchuria belonged to "China" (Zhongguo, Dulimbai gurun) in Qing edicts and in the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk.[49]

Population change

Despite migration restrictions, Qing rule saw massively increasing numbers of Han Chinese both illegally and legally streaming into Manchuria and settling down to cultivate land – Manchu landlords desired Han Chinese peasants to rent their land and to grow grain; most Han Chinese migrants were not evicted as they crossed the Great Wall and Willow Palisade. During the eighteenth century Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares of privately owned land in Manchuria and 203,583 hectares of lands which were part of courier stations, noble estates, and Banner lands; in garrisons and towns in Manchuria Han Chinese made up 80% of the population.[50]

The Qing resettled Han Chinese farmers from north China to the area along the Liao River in order to restore the land to cultivation.[51] Han Chinese squatters reclaimed wasteland, and other Han rented land from Manchu landlords.[52]

By the 18th century, despite officially prohibiting Han Chinese settlement on Manchu and Mongol lands, the Qing decided to settle Han refugees from northern China – who were suffering from famine, floods, and drought – into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, so that Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares in Manchuria and tens of thousands of hectares in Inner Mongolia by the 1780s.[53] The Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796) allowed Han Chinese peasants suffering from drought to move into Manchuria despite his having issued edicts in favor of banning them from 1740 to 1776.[54] Han Chinese then streamed into Manchuria, both illegally and legally, over the Great Wall of China and the Willow Palisade.[55] Chinese tenant farmers rented or even claimed title to land from the "imperial estates" and Manchu Bannerlands in the area.[56] Besides moving into the Liao area in southern Manchuria, Han Chinese settled the path linking Jinzhou, Fengtian, Tieling, Changchun, Hulun, and Ningguta during the Qianlong Emperor's reign, and Han Chinese had become the majority in urban areas of Manchuria by 1800.[57] To increase the Imperial Treasury's revenue, the Qing sold formerly Manchu-only lands along the Sungari to Han Chinese at the beginning of the Daoguang Emperor's 1820–1850 reign, and Han Chinese filled up most of Manchuria's towns by the 1840s, according to Abbé Huc.[58]

The demographic change was not caused solely by Han migration. Manchus also refused to stay in Manchuria. In the late 18th century, Manchus in Beijing were sent to Manchuria as part of a plan to reduce the burden on the court, but they tried to return by every means possible. With the exception of 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers and their families and a military colony established in the 1850s, Manchuria was devoid of Manchus. By 1900, almost 90 percent of Manchuria's 170 million inhabitants were Han Chinese.[1]

Russian invasions

The Russian conquest of Siberia was met with indigenous resistance to colonization, but Russian Cossacks crushed the natives. The conquest of Siberia and Manchuria also resulted in the spread of infectious diseases. Historian John F. Richards wrote: "... New diseases weakened and demoralized the indigenous peoples of Siberia. The worst of these was smallpox "because of its swift spread, the high death rates, and the permanent disfigurement of survivors." ... In the 1690s, smallpox epidemics reduced Yukagir numbers by an estimated 44 percent."[59] At the behest of people like Vasilii Poyarkov in 1645 and Yerofei Khabarov in 1650, Russian Cossacks killed some peoples like the Daur people of Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang to the extent that some authors speak of genocide.[60] The Daurs initially deserted their villages since they had heard about the cruelty of the Russians the first time Khabarov came.[61] The second time he came, the Daurs decided to do battle against the Russians instead, but were slaughtered by Russian guns.[62] The Russians came to be known as "red-beards".[63] The Amur natives called Russian Cossacks luocha (羅剎), after demons in Buddhist mythology, because of their cruelty towards the Amur tribespeople, who were subjects of the Qing.[64] The Qing viewed Russian proselytization of Eastern Orthodox Christianity to the indigenous peoples along the Amur River as a threat.[65]

In 1858 Russian diplomacy forced a weakening Qing dynasty to cede Manchuria north of the Amur to Russia under the Treaty of Aigun. In 1860, with the Treaty of Peking, the Russians managed to obtain a further large slice of Manchuria, east of the Ussuri River. As a result, Manchuria became divided into a Russian half (known as Outer Manchuria or Russian Manchuria, and a remaining Chinese region (known as Manchuria). In modern literature, "Manchuria" usually refers to Manchuria in China.[66] As a result of the Treaties of Aigun and Peking, Qing China lost access to the Sea of Japan.

History after 1860

Manchuria in China also came under strong Russian influence with the building of the Chinese Eastern Railway through Harbin to Vladivostok. In the Chuang Guandong movement, many Han farmers, mostly from the Shandong peninsula moved there. By 1921, Harbin, northern Manchuria's largest city, had a population of 300,000, including 100,000 Russians.[67] Japan replaced Russian influence in the southern half of Manchuria as a result of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904–1905. Most of the southern branch of the Chinese Eastern Railway was transferred from Russia to Japan, and became the South Manchurian Railway. Japanese influence extended into Outer Manchuria in the wake of the Russian Revolution of 1917, but Outer Manchuria had reverted to Soviet control by 1925. Manchuria was an important region due to its rich natural resources including coal, fertile soil, and various minerals. For pre–World War II Japan, Manchuria was an essential source of raw materials. Without occupying Manchuria, the Japanese probably could not have carried out their plan for conquest over Southeast Asia or taken the risk of attacking the United States and the British Empire in 1941.[68]

There was a major epidemic known as the Manchurian plague in 1910–1911, likely caused by the inexperienced hunting of marmots, many of whom are diseased. The cheap railway transport and the harsh winters, where the hunters sheltered in close confinement, helped to propagate the disease.[69] The response required close coordination between the Chinese, Russian and Japanese authorities and international disease experts held an 'International Plague Conference' in the northern city of Shenyang after the disease was under control to learn the lessons.[70]

It was reported that among Banner people, both Manchu and Chinese (Hanjun) in Aihun, Heilongjiang in the 1920s, would seldom marry with Han civilians, but they (Manchu and Chinese Bannermen) would mostly intermarry with each other.[71] Owen Lattimore reported that during his January 1930 visit to Manchuria, he studied a community in Jilin (Kirin), where both Manchu and Chinese Bannermen were settled at a town called Wulakai, and eventually the Chinese Bannermen there could not be differentiated from Manchus since they were effectively Manchufied (assimilated). The Han civilian population was in the process of absorbing and mixing with them when Lattimore wrote his article.[72]

Around the time of World War I, Zhang Zuolin established himself as a powerful warlord with influence over most of Manchuria. During his rule, the Manchurian economy grew tremendously, backed by the immigration of Chinese from other parts of China. The Japanese assassinated him on 2 June 1928, in what is known as the Huanggutun Incident.[73] Following the Mukden Incident in 1931 and the subsequent Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the Japanese declared Manchuria an "independent state", and appointed the deposed Qing emperor Puyi as puppet emperor of Manchukuo. Under Japanese control, Manchuria was brutally run, with a systematic campaign of terror and intimidation against the local populations including arrests, organised riots and other forms of subjugation.[74] Manchukuo was used by Japan as a base to invade the rest of China. At that time, hundreds of thousands of Japanese settlers arrived in Manchuria.

After the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan in 1945, the Soviet Union invaded from Outer Manchuria as part of its declaration of war against Japan. Soon afterwards, the Chinese Communist Party and Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) started fighting for control over Manchuria. The communists won in the Liaoshen Campaign and took complete control over Manchuria. With the encouragement of the Soviet Union, Manchuria was then used as a staging ground during the Chinese Civil War for the Chinese Communist Party, which emerged victorious in 1949. Ambiguities in the treaties that ceded Outer Manchuria to Russia led to disputes over the political status of several islands. The Kuomintang government in Taiwan (Formosa) complained to the United Nations, which passed resolution 505 on February 1, 1952, denouncing Soviet actions over the violations of the 1945 Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance.

As part of the Sino-Soviet split, this ambiguity led to armed conflict in 1969, called the Sino-Soviet border conflict, resulting in an agreement. In 2004, Russia agreed to transfer Yinlong Island and one half of Heixiazi Island to China, ending an enduring border dispute.

References

Citations

- Elliot 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 628.

- Narangoa 2002, p. 5.

- Li Narangoa (2002). "The Power of Imagination: Whose Northeast and Whose Manchuria?". Inner Asia. Brill. 4 (1): 3–25. JSTOR 23615422.

- Brummitt, R.K. (2001). World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions: Edition 2 (PDF). International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases For Plant Sciences (TDWG). p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- This is the sense used, e.g., in the World Geographical Scheme for Recording Plant Distributions.[4]

- Sino-Russian Treaty of Friendship (2001), Article 6.

- Complementary Agreement between the People's Republic of China and the Russian Federation on the Eastern Section of the China-Russia Boundary (2004).

- EB (1911).

- E.g. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society, Volumes 11–12 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, 1867, p. 162

- Nakami Tatsuo. "Qing China's Northeast Crescent: The Great Game." The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, Volume 2. David Wolff et al., eds. Brill, 2005. p. 514. Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 9789004154162"The use of the term 'Manchuria' as a place-name had begun with the Japanese in the eighteenth century, and it was later introduced to Europe by Philipp Franz von Siebold" [1796–1866].Giles 1912, p. 8 "It may be noted here that 'Manchuria' is unknown to the Chinese or to the Manchus themselves as a geographical expression. The present [1912] extensive home of the Manchus is usually spoken of as the Three Eastern Provinces,..."

- Elliot 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 626.

- Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback MachinePozzi 2006, p. 159.

- Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback MachinePozzi 2006, p. 167.

- Mark C. Elliott. The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press, 2001. p. 63. ISBN 9780804746847 "...the name 'Manchu' was officially adopted in 1635 as the name for all Jurchen people."

- Tamanoi 2000 Archived 2 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine, p. 249.

- Tamanoi 2005, p. 2-3.

- Philippe Forêt (January 2000). Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2293-4.

- Smith 2012 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 219.

- Narangoa 2002, p. 12.

- ed. Edgington 2003 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 114.

- McCormack 1977, p. 4 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Narangoa 2002, p. 18-19.

- Crossley 1999 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 55.

- Søren Clausen and Stig Thøgersen. The Making of a Chinese City: History and Historiography in Harbin. M. E. Sharpe, 1995. p. 7. Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 9781563244766 "In 1653 Jilin became an independent administrative unit, and in 1683 Heilongjiang was separated from Jilin. From then on, the three districts of Fengtian (roughly equivalent to present-day Liaoning), Jilin, and Heilongjiang became known as the "Three Eastern Provinces" (San dong sheng) although Jilin and Heilongjiang had not functioned as provinces in the full snese of the word until 1907–08."

- Oriental Affairs: A Monthly Review. 1935. p. 189.

- "The Controversial Manchuria". ThoughtCo.

- Hosie, Alexander (1910). Manchuria; its people, resources and recent history. Boston: J. B. Millet.

-

- Byington, Mark E. (2016). The Ancient State of Puyŏ in Northeast Asia: Archaeology and Historical Memory. Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London: Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 11, 13. ISBN 978-0-674-73719-8.

- Tamang, Jyoti Prakash (5 August 2016). Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of Asia. Springer. ISBN 9788132228004.

- Son, Chang-Hee (2000). Haan (han, Han) of Minjung Theology and Han (han, Han) of Han Philosophy: In the Paradigm of Process Philosophy and Metaphysics of Relatedness. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-1860-1.

- Xu, Stella (12 May 2016). Reconstructing Ancient Korean History: The Formation of Korean-ness in the Shadow of History. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-2145-1.

- Kallie, Szczepanski. "A Brief History of Manchuria". ThoughtCo.

- Lattimore, Owen (1934). "The Mongols of Manchuria". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. George Allen and Unwin, Ltd. 68 (4): 714–715. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00085245.

-

- Tamanoi, Mariko (2009). Memory Maps: The State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 10.

- Nishimura, Hirokazu; Kuroda, Susumu (2009). A Lost Mathematician, Takeo Nakasawa: The Forgotten Father of Matroid Theory. Springer. p. 15.

- Bogatikov, Oleg Alekseevich (2000); Magmatism and Geodynamics: Terrestrial Magmatism throughout the Earth's History; pp. 150–151; ISBN 90-5699-168-X

- Kropotkin, Prince P.; "Geology and Geo-Botany of Asia"; in Popular Science, May 1904; pp. 68–69

- Juo, A. S. R. and Franzlübbers, Kathrin Tropical Soils: Properties and Management for Sustainable Agriculture; pp. 118–119; ISBN 0-19-511598-8

- "Average Annual Precipitation in China". Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- Kaisha, Tesudo Kabushiki and Manshi, Minami; Manchuria: Land of Opportunities; pp. 1–2; ISBN 1-110-97760-3

- Kaisha and Manshi; Manchuria; pp. 1–2

- Earth History 2001 (page 15)

- The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 03: "Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1," at 32, 33.

-

- Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands By Mark Hudson Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Ledyard, 1983, 323

- Berger, Patricia A. Empire of emptiness: Buddhist art and political authority in Qing China. p.25.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2002). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-520-23424-6.

- Forsyth 1994 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 214.

- "5 Of The 10 Deadliest Wars Began In China". Business Insider. 6 October 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603–46. doi:10.2307/2658945

-

- Hauer 2007 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 117.

- Dvořák 1895 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 80.

- Wu 1995 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 102.

- Zhao 2006, pp. 4, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14.

- Richards 2003 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 141.

- Reardon-Anderson 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 504.

- Reardon-Anderson 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 505.

- Reardon-Anderson, James (2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia During the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. 5 (4): 503–509. doi:10.2307/3985584. JSTOR 3985584.

- Scharping 1998 Archived 6 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, p. 18.

- Richards, John F. (2003), The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World, University of California Press, p. 141, ISBN 978-0-520-23075-0

- Reardon-Anderson 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 507.

- Reardon-Anderson 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 508.

- Reardon-Anderson 2000 Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, p. 509.

- Richards, John F. (2003). The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. University of California Press. p. 538. ISBN 0-520-93935-2.

- For example:

Bisher, Jamie (2006) [2005]. White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. London: Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-135-76595-8. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

Armed resistance against the Russian conquest begat slaughters by both invaders and the original inhabitants, but the worst cases led to genocide of indigenous groups such as the Dauri people on the Amur River, who were hunted down and butchered during campaigns by Vasilii Poyarkov about 1645 and Yerofei Khabarov in 1650.

- "The Amur's siren song". The Economist (From the print edition: Christmas Specials ed.). 17 December 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Forsyth 1994 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 104.

- Stephan 1996 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 64.

- Kang 2013 Archived 23 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, p. 1.

- Kim 2012/2013 Archived 12 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, p. 169.

- "Manchuria | historical region, China | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- Memories of Dr. Wu Lien-teh, plague fighter Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Yu-lin Wu (1995). World Scientific. p.68. ISBN 981-02-2287-4

- Edward Behr, The Last Emperor, 1987, p. 202

- "Manchurian plague, 1910–11" Archived 8 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, disasterhistory.org, Iain Meiklejohn.

- In 1911, another epidemic swept through China. That time, the world came together. Archived 19 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine CNN, April 19, 2020

- Rhoads 2011 Archived 16 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine, p. 263.

- Lattimore 1933 Archived 12 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, p. 272.

- Edward Behr, ibid, p. 168

- Edward Behr, ibid, p. 202

Bibliography

- Bisher, Jamie (2006). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. ISBN 1-135-76596-0. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Clausen, Søren (1995). The Making of a Chinese City: History and Historiography in Harbin. Contributor: Stig Thøgersen (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1-56324-476-4. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (1999). A Translucent Mirror: History and Identity in Qing Imperial Ideology. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-92884-9. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Douglas, Robert Kennaway (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 552–554.

- Dvořák, Rudolf (1895). Chinas religionen ... Vol. 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Aschendorff (Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung). ISBN 0-19-979205-4. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (August 2000). "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies" (PDF). The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 59 (3): 603–646. doi:10.2307/2658945. JSTOR 2658945. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Elliott, Mark C. "The Limits of Tartary: Manchuria in Imperial and National Geographies." Journal of Asian Studies 59, no. 3 (2000): 603–46.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581–1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47771-9. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Gamsa, Mark, "Manchuria: A Concise History", Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

- Garcia, Chad D. (2012). Horsemen from the Edge of Empire: The Rise of the Jurchen Coalition (PDF) (A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy). University of Washington. pp. 1–315. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Giles, Herbert A. (1912). China and the Manchus. (Cambridge: at the University Press) (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons). Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- Hata, Ikuhiro. "Continental Expansion: 1905–1941". In The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press. 1988.

- Hauer, Erich (2007). Corff, Oliver (ed.). Handwörterbuch der Mandschusprache. Vol. 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05528-4. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Jones, Francis Clifford, Manchuria Since 1931, London, Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1949

- KANG, Hyeokhweon. Shiau, Jeffrey (ed.). "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons:The Korean Military Revolution and Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658" (PDF). Emory Endeavors in World History (2013 ed.). 4: Transnational Encounters in Asia: 1–22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Kim 金, Loretta E. 由美 (2012–2013). "Saints for Shamans? Culture, Religion and Borderland Politics in Amuria from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries". Central Asiatic Journal. Harrassowitz Verlag. 56: 169–202. JSTOR 10.13173/centasiaj.56.2013.0169.

- Kwong, Chi Man. War and Geopolitics in Interwar Manchuria (2017).

- Lattimore, Owen (July–September 1933). "Wulakai Tales from Manchuria". The Journal of American Folklore. American Folklore Society. 46 (181): 272–286. doi:10.2307/535718. JSTOR 535718.

- McCormack, Gavan (1977). Chang Tso-lin in Northeast China, 1911–1928: China, Japan, and the Manchurian Idea (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0945-9. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Narangoa, Li (2002), "The Power of Imagination: Whose Northeast and Whose Manchuria?", Inner Asia

- Masafumi, Asada. "The China-Russia-Japan Military Balance in Manchuria, 1906–1918." Modern Asian Studies 44.6 (2010): 1283–1311.

- Nish, Ian. The History of Manchuria, 1840–1948: A Sino-Russo-Japanese Triangle (2016)

- Pʻan, Chao-ying (1938). American Diplomacy Concerning Manchuria. The Catholic University of America. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Pozzi, Alessandra; Janhunen, Juha Antero; Weiers, Michael, eds. (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Akū Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Vol. 20 of Tunguso Sibirica. Contributor: Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-05378-X. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Reardon-Anderson, James (October 2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia during the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History. 5 (4): 503–530. doi:10.2307/3985584. JSTOR 3985584.

- Rhoads, Edward J. M. (2011). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-80412-5. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Scharping, Thomas (1998). "Minorities, Majorities and National Expansion: The History and Politics of Population Development in Manchuria 1610–1993" (PDF). Cologne China Studies Online – Working Papers on Chinese Politics, Economy and Society (Kölner China-Studien Online – Arbeitspapiere zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas). Modern China Studies, Chair for Politics, Economy and Society of Modern China, at the University of Cologne (1). Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Tamanoi, Mariko Asano (2005), Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire

- Sewell, Bill (2003). Edgington, David W. (ed.). Japan at the Millennium: Joining Past and Future (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0899-3. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Smith, Norman (2012). Intoxicating Manchuria: Alcohol, Opium, and Culture in China's Northeast. Contemporary Chinese Studies Series (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2431-6. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Stephan, John J. (1996). The Russian Far East: A History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2701-5. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Tamanoi, Mariko Asano (May 2000). "Knowledge, Power, and Racial Classification: The "Japanese" in "Manchuria"". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 59 (2): 248–276. doi:10.2307/2658656. JSTOR 2658656.

- Tao, Jing-shen, The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China. University of Washington Press, 1976, ISBN 0-295-95514-7.

- KISHI Toshihiko, MATSUSHIGE Mitsuhiro and MATSUMURA Fuminori eds, 20 Seiki Manshu Rekishi Jiten [Encyclopedia of 20th Century Manchuria History], Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2012, ISBN 978-4642014694

- Wu, Shuhui (1995). Die Eroberung von Qinghai unter Berücksichtigung von Tibet und Khams 1717–1727: anhand der Throneingaben des Grossfeldherrn Nian Gengyao. Vol. 2 of Tunguso Sibirica (reprint ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3-447-03756-3. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wolff, David; Steinberg, John W., eds. (2007). The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective: World War Zero, Volume 2. Vol. 2 of The Russo-Japanese War in Global Perspective (illustrated ed.). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004154162. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century" (PDF). Modern China. Sage Publications. 32 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014.