Eunicidae

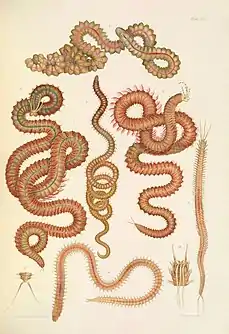

Eunicidae is a family of marine polychaetes (bristle worms). The family comprises marine annelids distributed in diverse benthic habitats across Oceania, Europe, South America, North America, Asia and Africa.[1] The Eunicid anatomy typically consists of a pair of appendages near the mouth (mandibles) and complex sets of muscular structures on the head (maxillae) in an eversible pharynx.[2] One of the most conspicuous of the eunicids is the giant, dark-purple, iridescent "Bobbit worm" (Eunice aphroditois), a bristle worm found at low tide under boulders on southern Australian shores. Its robust, muscular body can be as long as 2 m.[3] Eunicidae jaws are known from as far back as Ordovician sediments.[4][5] Cultural tradition surrounds Palola worm (Palola viridis) reproductive cycles in the South Pacific Islands.[6] Eunicidae are economically valuable as bait in both recreational and commercial fishing.[7][8] Commercial bait-farming of Eunicidae can have adverse ecological impacts.[9] Bait-farming can deplete worm and associated fauna population numbers,[10] damage local intertidal environments [11] and introduce alien species to local aquatic ecosystems.[12]

| Eunicidae Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eunice aphroditois | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Annelida |

| Class: | Polychaeta |

| Order: | Eunicida |

| Family: | Eunicidae Berthold, 1827 |

| Genera | |

In 2020, Zanol et al. stated, "Species traditionally considered to belong to Eunice are now, also, distributed in two other genera Leodice and Nicidion recently resurrected to reconcile Eunicidae taxonomy with its phylogenetic hypothesis."[13]

History of knowledge

In 1992, Kristian Fauchald detailed a conclusive history of research and classification of the Eunicidae family.[4] Primary studies undertaken in 1767 on coral reefs in Norway, initially classified Eunicid species under the Nereis family.[4] In 1817, Georges Cuvier created a new genus, Eunice, to classify these and other original taxa.[4] Throughout the 1800s (1832-1878) worm species were added to this genera by Jean Victor Audouin and Henri Milne-Edwards, Kinberg, Edwardsia de Quatrefages, Malmgren, Ehlers and Grube.[4] Following the Challenger and Albatross expeditions, research was expanded by McIntosh and Chamberlain.[4] In 1921 and 1922, Treadwell added new species from coral reefs in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean.[4] Species were reviewed and their classifications were refined by Fauvel, Augener and Hartman throughout the early 1900s.[4] In 1944, Hartman codified a system of separate classification for the family, informally grouping North American species using the original suggestions of Ehlers.[4] Hartman's system was expanded and specified by Fauchald in 1970 and later again by Miura in 1986.[4]

Taxonomy

Thirty-three genera have been described in the Eunicidae family.[14] Only eight are currently considered valid:[15]

- Aciculomarphysa (Hartmann-Schroeder, 1998 in Hartmann-Schroder & Zibrowius 1998)

- Eunice (Cuvier, 1817)

- Euniphysa (Wesenberg-Lund, 1949)

- Fauchaldius (Carrera-Parra & Salazar-Vallejo, 1998)

- Lysidice (Lamarck, 1818)

- Marphysa (Quatrefages, 1866)

- Nematonereis (Schmarda, 1861)

- Palola (Gray in Stair, 1847)

Anatomy

Segmented body

Members of the Eunicidae family are distinguished from other families in Eunicida by having a rear segment with 1-3 antennae and no ringed bases on their antennae.[16] The first body segment of Eunicidae is either whole or consists of two lobes.[16] The gills of live specimens are typically identifiable by their bright red colour.[17]

Head and jaws

A pair of slender and cylindrical sensory appendages are typically situated near the head of Eunicidae.[16] The lips of Eunicidae can be either reduced or well-developed.[16] In the Eunice species, worms have five appendages on two elongated segmented appendages and three antennae near their heads.[16] This feature is not part of the anatomy of all genera in the Eunicidae family. Eunicidae jaws are typically well developed and partly visible on the underside of the worm or on its surface at the front of the mouth in a complex structure.[16][17]

Ecology

Distribution and habitat

Eunicidae are distributed in diverse benthic habitats across Oceania, Europe, South America, North America, Asia and Africa. Eunicids play an ecological role in benthic communities, exhibiting a preference for subtidal hard substrates in shallow temperate waters, tropical waters and mangrove swamps.[1][4] Most species of Eunicidae inhabit cracks and crevices in assorted rubble, rock, and sand environments.[4] In limestone or coral reefs, Eunicids burrow into hard parchment-like tube corals or remain in crevices of calcareous algae.[18]

Diet

Eunicid diets vary across genera. For example, the Eunice aphroditois crawl on the seafloor where they scavenge in a carnivorous feeding pattern on marine worms, small crustaceans, molluscs, algae and detritus.[2][14][19][20][21] Other species, for example Euniphysa tubifex and large Eunice, hunt the surrounds of their coral habitats and feed on the decaying flesh of dead sea-life.[2][22] Burrowing species of Eunicidae (Lysidice and Palola) are primarily herbivores. These species feed on matured corals and contained organisms or on types of algae.[23] The diet of Marphysa species of Eunicidae is variable, some worms are herbivores,[21] some are carnivores [24] and others omnivores.[2][22]

Threats

The practice of harvesting polychaetes (including species in the Eunicidae family) as bait may have negative ecological impacts on intertidal habitats and on worm population numbers.[9][11] In 2019, Cabral et al. found that Marphysa sanguinea are placed at risk by overfishing and unlicensed harvesting in Portugal.[9] The ecological impacts of bait harvesting activity can also affect associated fauna populations [10] as well as sediment quality [25] and bioavailability of heavy metals.[26][9] Research indicates that mudworm survival and growth may also be affected by changes in salinity rates.[27]

Ecological impact

Importing Eunicidae species is an established alternative to exploiting local populations for bait.[12] This process may lead to accidental species introductions or invasions.[28][29] Alien species can threaten the foundation of local ecosystems by altering food webs, habitat structures and gene pools.[28] Alien species can also introduce diseases and parasites.[29][30] Six species of Eunice, one species of Euniphysa, three species of Lysidice and one species of Marphysa sp. were identified as alien in local aquatic ecosystems across the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the USA Pacific and the North Sea.[28] Live bait worms are often emptied into the water body by anglers at the end of a fishing session, this is another practice that can introduce alien species to aquatic ecosystems.[12][28][29]

Life cycle

Sexual reproduction

Most of the class Polychaeta are benthic sexual reproductive animals and lack external reproductive organs.[31] When mating, female polychaetes produce a pheromone that induces a mutual release of male sperm and female eggs. This process of synchronous reproduction in the form of a swarm is known as epitoky. During this process, there is no actual male to female contact. The reproductive swarm is ejected into open water. Cells that fuse during fertilisation (gametes) are spawned through an excretory gland (metanephridia) or by the main worm body-wall rupturing.[32] Post-fertilisation, most eggs become planktonic; although some remain inside the worm tubes or burrow in external jelly masses attached to the tubes.[32] Epitokes can draw an increased number of pelagic predators.[6] In the Florida Keys for example, the swarming of Eunice fucata is a highly publicised in local fishing communities, attracting a large gathering of tarpon.[6] These mass swarming events, or ‘risings’, are a spectacle that is the foundation of local tradition in Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Kiribati and Indonesia.[1]

Human relations

As bait in commercial and recreational fishing

Marphysa sanguinea, or known locally in Italy as “Murrido”, “Murone”, “Bacone” and “Verme sanguigno” is the most valuable bait of all Polychaete species collected in Italy.[7] This species is also cultivated in USA and South Korea and is typically commercially harvested once at its optimal length of 20–30 cm.[7] Marphysa sanguinea can reach up to 50 cm long and is collected by excavating in deep sediment.[8] For example, in the Venice lagoon, fisherman dig below the sediment layers colonised by the nereidids and sieve organic material through coarse screens.[33] This process is also common in Italian coastal areas with intertidal and shallow littoral muddy bottoms.[7] Eunice aphroditois, another sizeable (up to 1 metre in length) species of Eunicidae, is harvested by scuba divers along the Italian Apulia coasts.[7] This species is collected at soft bottom ocean floors at a depth of 10 metres using specialised harvesting instruments that fit into U-shaped parchment tubes where the worm lives.[8] This species of Eunicidae is suitable bait for fish of the Sparidae family and is used in commercial hook and line practice.[7] Species within the Eunicidae family are also caught by recreational and commercial fisherman in estuaries along the West coast of Portugal and in Arcahon Bay in France.[7][34] Marphysa are propagated and harvested in Australian estuary communities located along the coast of New South Wales and Queensland.[34] Collecting of Marphysa moribidii as bait occurs along the West coast of Peninsular Malaysia, Marphysa elityeni are caught in subsistence fisheries in Africa and Eunice sebastiani have been reported as being harvested for bait in Brazil.[34] Eunicids are also used as supplementary feed for aquaculture.[8][35][36][37] For example, mudworms are a part of the black tiger prawn diet in some Thailand hatcheries.[35][38]

In legend and culture

In the Indo-Pacific, during 1-2 nights each year, the epitokes of the Palola viridis species are automatised.[1][6] The sizeable epitokes (up to 30 cm in length) swim autonomously upwards and rupture, releasing gametes across the surface of the ocean.[1] The epitokes are composed of hundreds of segments, with females emerald in colour and males transitioning from orange to brown during maturation.[6] On ‘rising’ night it is tradition for some local communities to attract epitokes with artificial light sources or using other traditional methods.[34] In Samoa for example, locals wear necklaces made of mosoʻoi flowers and use the fragrant floral scent to attract Palola worms.[34] The epitokes are scooped from the shallows into nets and containers to be consumed raw, or cooked, baked, dried or frozen for later consumption.[34]

See also

References

- Rouse, G. W; Pleijel, F. (2001). "ROUSE, G. W. & PLEIJEL, F. 2001. Polychaetes. Xiii + 354 pp. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Price £109.50. ISBN 0 19 850608 2". Geological Magazine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 140 (5): 617–618. doi:10.1017/S0016756803278341. S2CID 86760716.

- Fauchald, K; Jumars, P. A. (1979). "The Diet of Worms: A Study of Polychaete Feeding Guilds". Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review. Aberdeen University Press. 17: 193–284.

- Keith Davey (2000). "Eunice aphroditois". Life on Australian Seashores. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- Fauchald, K. (1992). "A review of the genus Eunice (Polychaeta: Eunicidae) based upon type material" (PDF). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology. 523 (523): 1–422. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.523.

- Parry, Luke; Tanner, Alastair; Vinther, Jakob (2015). "The Origin of Annelids". Palaeontology. The Palaeontological Association. 57 (6): 1091–1103. doi:10.1111/pala.12129.

- Schulze, Anja; Timm, Laura E. (2011). "Palolo and un: distinct clades in the genus Palola (Eunicidae, Polychaeta)". Marine Biodiversity. 42 (2): 161–171. doi:10.1007/s12526-011-0100-5. ISSN 1867-1616. S2CID 12617958.

- Gambi, M. C.; Castelli, A.; Giangrande, A.; Lanera, P.; Prevedelli, D.; Zunarelli Vandini, R. (1994). "Polychaetes of Commercial and Applied Interest in Italy: An Overview". Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. 162: 593–603.

- Olive, P. J. W. (1994). "Polychaeta as a World Resource: A Review of Patterns of Exploitation as Sea Angling Baits, and Potential for Aquaculture Based Production". Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. 162: 603–610.

- Cabral, Sara; Alves, Ana Sofia; Castro, Nuno; Chainho, Paula; Sá, Erica; Cancela da Fonseca, Luís; Fidalgo e Costa, Pedro; Castro, João; Canning-Clode, João; Pombo, Ana; Costa, José Lino (2019-11-01). "Polychaete annelids as live bait in Portugal: Harvesting activity in brackish water systems". Ocean & Coastal Management. 181: 104890. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104890. ISSN 0964-5691. S2CID 200044214.

- Birchenough, S. (2013). "Impact of Bait Collecting in Poole Harbour and Other Estuaries within the Southern IFCA District". South. Inshore Fish Conserv. Auth.: 117.

- Carvalho, André Neves de; Vaz, Ana Sofia Lino; Sérgio, Tânia Isabel Boto; Santos, Paulo José Talhadas dos (2013). "Sustainability of bait fishing harvesting in estuarine ecosystems – Case study in the Local Natural Reserve of Douro Estuary, Portugal". Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada. 13 (2): 157–168. doi:10.5894/rgci393. ISSN 1646-8872.

- Martin, Daniel; Gil, João; Zanol, Joana; Meca, Miguel A.; Portela, Rocío Pérez (2020-05-21). "Correction: Digging the diversity of Iberian bait worms Marphysa (Annelida, Eunicidae)". PLOS ONE. 15 (5): e0233825. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1533825M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233825. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 7241716. PMID 32437422.

- Zanol, Joana; Hutchings, Pat A.; Fauchald, Kristian (5 March 2020). "Eunice sensu lato (Annelida: Eunicidae) from Australia: description of seven new species and comments on previously reported species of the genera Eunice , Leodice and Nicidion". Zootaxa. 4748 (1): zootaxa.4748.1.1. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4748.1.1. PMID 32230084. S2CID 214751173.

- Zanol, J.; Halanych, M.; Fauchald, K. (2013). "Reconciling Taxonomy and Phylogeny in the Bristleworm Family Eunicidae (Polychaete, Annelida)". Zoologica Scripta. 43 (1): 79–100. doi:10.1111/zsc.12034. S2CID 86823981.

- "World Polychaeta Database". www.marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

- Paxton, Hannelore (2000). Polychaetes & Allies: The Southern Synthesis. Vol. 4A. Commonwealth of Australia. pp. 127–130.

- Wilson, RS; Hutchings, PA; Glasby, CJ. "Polychaetes: An Interactive Identification Guide". researchdata.museum.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-11-19.

- Hutchings, P. A. (1986). "Biological Destruction of Coral Reefs: A Review". Coral Reefs. 4 (4): 239–252. Bibcode:1986CorRe...4..239H. doi:10.1007/BF00298083. ISSN 0722-4028. S2CID 34046524.

- Hempelmann, F. (1931). Kükenthal, W.; Krumbach, T. (eds.). "Handbuch der Zoologie". Lief. 2: 12–13 – via De Gruyter & Co.

- Evans, S. M. (1971). "Behavior in Polychaetes". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 46 (4): 379–405. doi:10.1086/407004. ISSN 0033-5770. S2CID 85113678.

- Yonge, C.M (1954). "Tabulæ Biologicæ Periodicæ". Nature. 21(3) (3272): 25–45. doi:10.1038/130078c0. S2CID 45909112.

- Day, J.H. (1967). "A Monograph on the Polychaeta of Southern Africa Part 1, Errantia: Part 2, Sedentaria". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Trustees of the British Muséum (Natural History). 656: 878 – via CambridgCore.

- Fauchald, Kristian (1992). "A Review of the Genus Eunice (Polychaeta: Eunicidae) Based upon Type Material". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology (523): 1–422. doi:10.5479/si.00810282.523. hdl:10088/6302.

- Desiere, M. (1967). "Annales de la Société Royale Zoologique de Belgique". Société Royale Zoologique de Belgique. 97: 65–90.

- Anderson, Franz E.; Meyer, Lawrence M. (1986). "The interaction of tidal currents on a disturbed intertidal bottom with a resulting change in particulate matter quantity, texture and food quality". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 22 (1): 19–29. Bibcode:1986ECSS...22...19A. doi:10.1016/0272-7714(86)90021-1. ISSN 0272-7714.

- Falcão, M.; Caetano, M.; Serpa, D.; Gaspar, M.; Vale, C. (2006). "Effects of infauna harvesting on tidal flats of a coastal lagoon (Ria Formosa, Portugal): Implications on phosphorus dynamics". Marine Environmental Research. 61 (2): 136–148. doi:10.1016/j.marenvres.2005.08.002. ISSN 0141-1136. PMID 16242182.

- Garcês, J. P.; Pereira, J. (2010-09-03). "Effect of salinity on survival and growth of Marphysa sanguinea Montagu (1813) juveniles". Aquaculture International. 19 (3): 523–530. doi:10.1007/s10499-010-9368-x. ISSN 0967-6120. S2CID 42717696.

- Çinar, Melih Ertan (2012). "Alien Polychaete Species Worldwide: Current Status and their Impacts". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Cambridge University Press. 93 (5): 1257–1278. doi:10.1017/S0025315412001646. ISSN 0025-3154. S2CID 201191494 – via CambridgeCore.

- Font, Toni; Gil, João; Lloret, Josep (2017). "The Commercialisation and use of Exotic Baits in Recreational Fisheries in the North-Western Mediterranean: Environmental and Management Implications". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 28 (3): 651–661. doi:10.1002/aqc.2873. hdl:10261/160084.

- Occhipinti Ambrogi, A. (2001). "Transfer of Marine Organisms: A Challenge to the Conservation of Coastal Biocoenoses". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 11 (4): 243–251. doi:10.1002/aqc.450.

- Mastrototaro, F.; Giove, A.; D'Onghia, G.; Tursi, A.; Matarrese, A.; Gadaleta, M.V. (2008). "Benthic diversity of the soft bottoms in a semi-enclosed basin of the Mediterranean Sea". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 88 (2): 247–252. doi:10.1017/S0025315408000726. ISSN 0025-3154. S2CID 85774255.

- Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S.; Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology. A functional evolutionary approach (7th ed.). Thomson Learning: Brooks/Cole. p. 990.

- Hutchings, P. A. (1986). "Biological destruction of coral reefs: A review". Coral Reefs. 4 (4): 239–252. Bibcode:1986CorRe...4..239H. doi:10.1007/BF00298083. ISSN 0722-4028. S2CID 34046524.

- Cole, Victoria J.; Chick, Rowan C.; Hutchings, Patricia A. (2018). "A review of global fisheries for polychaete worms as a resource for recreational fishers: diversity, sustainability and research needs". Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. 28 (3): 543–565. doi:10.1007/s11160-018-9523-4. ISSN 0960-3166. S2CID 49354510.

- Mandario, Mary Anne E. (2020). "Survival, growth and biomass of mud polychaete Marphysa iloiloensis (Annelida: Eunicidae) under different culture techniques". Aquaculture Research. 51 (7): 3037–3049. doi:10.1111/are.14649. ISSN 1355-557X. S2CID 219091475.

- Alava, V. R., Biñas, J. B., & Mandario, M. A. E. (2017). Breeding and culture of the polychaete, Marphysa mossambica, as feed for the mud crab. In E. T. Quinitio, F. D. Parado-Estepa, & R. M. Coloso (Eds.), Philippines : In the forefront of the mud crab industry development : proceedings of the 1st National Mud Crab Congress, 16–18 November 2015, Iloilo City, Philippines (pp. 39–45). Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines: Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. https://repository.seafdec.org.ph/handle/10862/3197

- Naessens, E.; Lavens, P.; Gomez, L.; Browdy, C.L.; McGovern-Hopkins, K.; Spencer, A.W.; Kawahigashi, D.; Sorgeloos, P. (1997). "Maturation performance of Penaeus vannamei co-fed Artemia biomass preparations". Aquaculture. 155 (1–4): 87–101. doi:10.1016/S0044-8486(97)00111-7.

- Meunpol, Oraporn; Meejing, Panadda; Piyatiratitivorakul, Somkiat (2005). "Maturation diet based on fatty acid content for male Penaeus monodon (Fabricius) broodstock". Aquaculture Research. 36 (12): 1216–1225. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01342.x. ISSN 1355-557X.