Eurasia Tunnel

The Eurasia Tunnel (Turkish: Avrasya Tüneli) is a road tunnel in Istanbul, Turkey, crossing underneath the Bosphorus strait. The tunnel was officially opened on 20 December 2016[4][5][6] and opened to traffic on 22 December 2016.

Kumkapı entrance to Eurasia Tunnel | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Avrasya Tüneli |

| Location | Bosphorus Strait, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Coordinates | 41°00′17″N 28°59′41″E |

| Status | Open |

| Route | |

| Start | Kumkapı, Fatih (Europe) |

| End | Haydarpaşa (Asia) |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 26 February 2011 |

| Opened | 22 December 2016 |

| Owner | Eurasia Tunnel Operation Construction and Investment Inc. (ATAŞ) (until operation period) Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure (after operation period) |

| Operator | Eurasia Tunnel Operation Construction and Investment Inc. (ATAŞ) Egis Tunnels |

| Traffic | car, minibus, van, motorcycle |

| Character | Undersea, double-deck tunnel |

| Toll | 53 TRY for automobiles 79.5 TRY for minibuses, 20.7 TRY for motorcycles[1] Half toll applies 00:00-04:59 |

| Technical | |

| Length | 5.4 km (3.4 mi)[2] |

| No. of lanes | 2 x 2 |

| Operating speed | 70 km/h (43 mph)[3] |

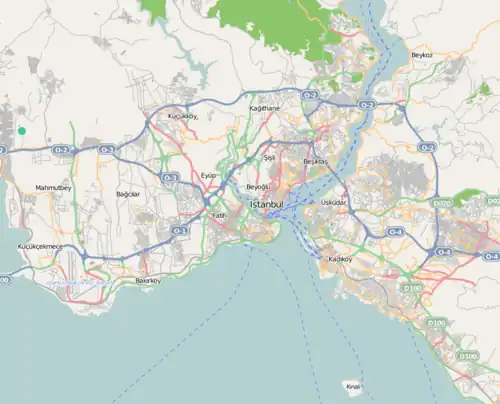

The 5.4 km (3.4 mi) double-deck tunnel connects Kumkapı on the European part and Koşuyolu, Kadıköy, on the Asian part of Istanbul[7] with a 14.6 km (9.1 mi) route including the tunnel approach roads.[8] It crosses the Bosphorus beneath the seabed at a maximum depth of −106 m (348 ft).[9][10][11] It is about 1 km (0.62 mi) south of the undersea railway tunnel Marmaray, which was opened on 29 October 2013.[12] The journey between the two continents takes about 5 minutes.[4][8][10][13] Toll is collected in both directions; since February 2020, ₺36.40 (about $4 US) for cars and ₺54.70 ($6 US) for minibuses.[14] In February 2021 the toll increased by 26% to ₺46 (approx. $6.20) and ₺69 (~$9.30) respectively.[1]

Background

In 1891, French railway engineer Simon Préault presented a preliminary project for an underwater tubular bridge "patented by the Ottoman imperial government", consisting of a submerged bridge supporting a tube where steam trains would run.[15]

The conceptual background of Eurasia Tunnel reaches back to the findings of the 1997 Transportation Master Plan undertaken by Istanbul University on behalf of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. Based on this plan, a pre-feasibility study had been conducted in 2003 for a new Bosphorus crossing. According to the results of this study, a road tunnel was recommended as the solution that offered the highest degree of feasibility.[4][16]

The Ministry of Transportation, Maritime and Communication of Turkey commissioned a feasibility study by Nippon Koei Co. Ltd. in 2005 to assess route alternatives for a new tunnel crossing. Based on environmental and social criteria, cost and risk factors, the study concluded by supporting the initially proposed route as the preferred option.

The three current bridges across the Bosphorus were taken into consideration in selecting the tunnel's location, which was put farther south to better balance the distribution of traffic between the crossings. Other selection criteria included the route's lower investment cost due to a shorter tunnel length and the availability of sufficient space for construction sites and operational buildings (toll plaza, administrative units). High level assessments based on corridor alternatives that are comprehensively defined in the feasibility study also support the selection of the proposed route in terms of environmental and social costs and risk factors.

Investors

Avrasya Tüneli İşletme İnşaat ve Yatırım A.Ş. (ATAŞ) was founded on 26 October 2009 by the partnership of Yapı Merkezi from Turkey and SK E&C from South Korea.[4][16]

The build–operate–transfer model adopted at the Eurasia Tunnel, has brought together the private investment dynamism and their project experience, and the support of international financial institutions.[4][16] The concession lasts 29 years.[4] Partnership contract includes guaranteed minimum revenue and profit sharing for parts exceeding guaranteed revenue.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is supplying a finance package worth US$150 million. Other components of the US$1.245 billion financing package include a $350 million loan from the European Investment Bank (EIB) and financing and guarantees from Export-Import Bank of Korea and K-Sure, also with participation from Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, Standard Chartered, Mizuho Bank, Türkiye İş Bankası, Garanti Bank and Yapı ve Kredi Bankası. A hedging facility for the transaction is provided by some of the lenders as well as Deutsche Bank.[4]

Project segments

The project consists of three main segments:

- European side

Construction of five U-turns as underpasses and seven pedestrian crossings as overpasses along Kennedy Street that stretches between Kazlıçeşme and Sarayburnu as a shoreline road beside the Sea of Marmara. Widening of the entire Segment 1, which is approximately 5.4 km (3.4 mi), from 3x2 lanes to 2x4 lanes.[4][11][16]

- Bosphorus crossing

Construction of a 5.4 km (3.4 mi), two-deck road tunnel with two lanes on each deck, a toll plaza and an administrative building on the western end and ventilation shafts on both ends of the tunnel.[4][11]

- Asian side

Widening from 2x3 and 2x4 lanes to 2x4 and 2x5 lanes along an approximately 3.8 km (2.4 mi) stretch of the current D100 road that links at Göztepe to Ankara-İstanbul State Highway, and construction of 2 bridge intersections, 1 overpass and 3 pedestrian bridges.[4][11]

Technical details

The American firm Parsons Brinckerhoff was responsible for the design, while the British Arup Group[13] and American Jacobs Engineering Group undertook the technical and traffic studies and HNTB provided independent design verification. The geotechnical survey was by the Dutch consultancy Fugro.[17] The tunnel boring machine (TBM) was supplied by the German manufacturer Herrenknecht.[18] The Italian company Italferr was in charge of works management and project review on behalf of Administration.[19] The French company Egis Group will be in charge of the operation and maintenance.[20]

The TBM section crossing the Bosphorus is 3.4 km (2.1 mi) long while another 2.0 km (1.2 mi) is constructed by the New Austrian Tunnelling method (NATM) and cut-and-cover method. The tunnel's excavation diameter is 13.7 m (45 ft),[18] which allows an inner diameter of 12.0 m (39.4 ft) with 60 cm (23.6 in)-thick lining.[4][11]

The tunnel alignment is located in a seismically active region, about 17 km (11 mi) to the North Anatolian Fault Zone. To decrease the seismic stresses/strains below the permissible levels, two flexible seismic joints/segments; with displacement limits of ±50 mm (1.97 in) for shear and ±75 mm (2.95 in) for extraction/contraction; were innovated, designed specially, localized through geological/geophysical/geotechnical conditions, tested in laboratory; implemented ‘first time’ in TBM tunnelling under similar severe conditions. The design earthquake magnitude was specified as moment magnitude of 7.25 and design of functional and safety evaluation earthquakes have a return period of 500 and 2,500 years, respectively. Seismic joint locations defined during design phase were verified through continuous monitoring of cutterhead torques.

The 3,340 m (3,650 yd) tunnel was excavated and constructed with a 13.7 m (45 ft) diameter Mixshield Slurry TBM exclusively designed and equipped with the latest 19 in (483 mm)} disc cutters (35 pieces monoblock disc cutters, all atmospherically changeable and have individual wearing sensor system), 192 piece cutting knives (only 48 atmospherically changeable), special pressurized locks for divers and material and rescue chamber for all shift members. Slurry Treatment Plant (installed power of 3.5 MW or 4,700 hp which de-silts the bentonite slurry used during excavation and regenerates with 2,800 m3/h (99,000 cu ft/h) capacity (approximately equivalent to 20 m/d or 66 ft/d) was installed. The utilized TBM ranks first in the world with its 33 kW/m2 (4.1 hp/sq ft) cutterhead power, second with its 12.0 bar (1.20 MPa; 174 psi) pressure design; and sixth with its 147 m2 (1,580 sq ft) excavation area.

TBM operation was completed within ±5 cm (1.97 in) tolerance in 479 calendar days, resulting in an average advance rate of 7.0 m/d (23 ft/d) (9.0 m/d or 30 ft/d for working days) by three crews 24/7. The maximum advance rate was realized at marine sediment zone with 18.0 m/d (59 ft/d). Spent direct time for excavation and ringbuild were around 3,500 and 1,700 hours, respectively. In Trakya formation, 28 dyke zones were excavated with an average frequency of 90 m (300 ft) and thicknesses were varying between 1 and 120 m (3.3 and 393.7 ft). Furthermore, 440 disc cutters, 85 scrapers and 475 brushes were replaced by TBM crew and four times hyperbaric maintenance operations (total of 45 days) with specially trained divers (max. under 10.8 bar or 1.08 MPa or 157 psi first time in the world) were successfully performed.

15,048 piece 600 mm (23.62 in)-thick precast segments (1,672 rings) with the high performance (average charge passed is 280 Coulomb (1,000 Coulomb limit) were produced and connected to each other by using 30,765 bolts. Each ring consists of nine segments that had an average 28 day cylinder compressive strength of 70 MPa (10,000 psi) and can resist at least 127 years as a service life against subsea conditions. Only 0.3% of produced segments were found to be deficient due to existence of cracks width more than 0.2 mm (0.008 in).

On the other hand, twin tunnels (each has approximately 950 m or 3,120 ft length) were completed in 445 calendar days with a cross section of 85 m2 (910 sq ft) each by classical mining method. These tunnels were excavated in Trakya Formation from four faces with a 1.4 m/d (4.6 ft/d)/face advance rate under a densely populated district with minimum and maximum overburden of 8 and 41 m (26 and 135 ft), respectively. Both tunnels met up each other within ±2 mm (0.079 in) tolerance. The largest converge measured at the tunnel crown was 33 mm (1.30 in) (design tolerance is 50 mm or 1.97 in) with a maximum 10 mm (0.39 in) surface settlement.

The tunnel is designed so that it has protected emergency areas every 200 m (220 yd) to provide shelter, also escape routes to the other tunnel level. Every 600 m (660 yd) there will be an emergency lane equipped with emergency telephone.[4]

The speed limit in the tunnel route 70 km/h (43 mph).

A daily average of around 120,000 cars and light vehicles is expected to pass through the tunnel after the first year.[13][16]

The toll is planned to be Turkish lira equivalent of $4 US plus VAT for cars and $6 US plus VAT for minibuses in each direction. The toll rate will change in accordance with US Consumer Price Index.[11]

See also

- Bosphorus Bridge, also called the First Bosphorus Bridge.

- Bosphorus Strait

- Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, also called the Second Bosphorus Bridge, located about 5 km north of the Bosphorus Bridge.

- Great Istanbul Tunnel, a proposed undersea tunnel.

- Marmaray, undersea rail tunnel, crossing the Bosphorus and connecting the Asian and European sides of Istanbul.

- Public transport in Istanbul

- Rail transport in Turkey

- Turkish Straits

- Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge, also called the Third Bosphorus Bridge.

References

- "Eurasia Tunnel Toll Rates as of 1 February 2021". Avrasya Tüneli. February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- Mesut Altun (19 December 2016). "Son dakika haberi: Avrasya Tüneli yarın açılıyor" [Breaking news: Eurasia Tunnel opens tomorrow]. Sabah. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- Avrasya Tüneli Safety Brochure. Avrasyatuneli.com

- "Eurasia Tunnel Project" (PDF). Unicredit - Yapı Merkezi, SK EC Joint Venture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-20. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Istanbul's $1.3BN Eurasia Tunnel prepares to open". Anadolu Agency. 19 December 2016.

- "Eurasia Tunnel opens, linking Europe and Asia in 15 minutes". Daily Sabah. 20 December 2016.

- While, for both directions, the mouth openings of the tunnel on the Asian side are situated in the Haydarpaşa quarter, the access roads begin or end in the adjacent Koşuyolu quarter.

- "Çift katlı Avrasya Tüneli'nde kazı işlemi devam ediyor" [Excavation continues in the double-deck Eurasia Tunnel]. Hürriyet (in Turkish). 2013-09-03. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Avrasya tüneli'nin temeli atıldı" [Foundation of Eurasia tunnel laid]. Zaman (in Turkish). 2011-02-26. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Dev köstebek boğazın altını delmeye başlıyor" [Giant mole begins to pierce the bottom of the narrows]. Hürriyet (in Turkish). 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the Eurasia Tunnel Project Istanbul, Turkey" (PDF). ERM Group, Germany and UK & ELC-Group, Istanbul. January 2011. p. 42. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- "Marmaray tunnel completed". Railway Gazette. 2008-10-20. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- "Istanbul Strait Tunnel (Eurasia Tunnel)". Arup. Archived from the original on 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- "Eurasia Tunnel Toll Rates as of 1 February 2020". Avrasya Tüneli. January 31, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- "ERHAN AFYONCU - Proje tarihi 3 Ağustos 1891" [ERHAN AFYONCU - Project date August 3, 1891]. Sabah.com.tr. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- "Eurasia Tunnel Project, Istanbul, Turkey". Road Traffic. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- "Onshore & Offshore Geotechnics - Eurasia Tunnel Project" (PDF). Fugro. Retrieved 2014-04-15.

- "Başbakan Erdoğan, 'Yıldırım Bayezid'le Avrasya Tüneli'ni kazmaya başladı" [Prime Minister Erdoğan started to dig the Eurasia Tunnel with Yıldırım Bayezid]. Radikal (in Turkish). 2014-04-19. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- A Italferr la supervisione lavori del Tunnel Eurasia e la revisione del progetto. (tr. "Italferr supervised the works of the Eurasia Tunnel and reviewed the project")Archived 2017-05-12 at the Wayback Machine Italferr, 2014.

- Galante, Grace: The Eurasia tunnel under the Bosphorus opens to the public. Archived 2019-02-13 at the Wayback Machine ccworldconstruction.com, December 21, 2016.

External links

- Official website

- Connecting Continents. In: All Around, No. 4 / Herrenknecht AG, large-screen pics of the tunnel construction