White Haitians

White Haitians (French: Blancs haïtiens, [blɑ̃ (s)aisjɛ̃]; Haitian Creole: blan ayisyen),[1] also known as Euro-Haitians, are Haitians of predominant or full European descent.[2] There were approximately 20,000 whites around the Haitian Revolution, mainly French, in Saint-Domingue. They were divided into two main groups: The Planters and Petit Blancs.[3] The first white Europeans to settle in Haiti were the Spanish.[4] The Spanish enslaved the indigenous Haitians to work on sugar plantations and in gold mines. European diseases such as measles and smallpox killed all but a few thousand of the indigenous Haitians. Many other indigenous Haitians died from overwork and harsh treatment in the mines from slavery.[5]

History

European conquest and colonization

The presence of whites in Haiti dates back to the founding of La Navidad, the first European settlement in the Americas by Christopher Columbus in 1492. It was built from the timbers of his wrecked ship Santa María, during his first voyage in December 1492. When he returned in 1493 on his second voyage he found the settlement had been destroyed and all 39 settlers killed. Columbus continued east and founded a new settlement at La Isabela on the territory of the present-day Dominican Republic in 1493. The capital of the colony was moved to Santo Domingo in 1496, on the south east coast of the island also in the territory of the present-day Dominican Republic. The Spanish returned to western Hispaniola in 1502, establishing a settlement at Yaguana, near modern-day Léogâne. A second settlement was established on the north coast in 1504 called Puerto Real near modern Fort-Liberté – which in 1578 was relocated to a nearby site and renamed Bayaha.[6][7][8] The Spanish began to enslave the indigenous Taíno and Ciboney people soon after December 1492.[9]

The settlement of Yacanagua was burnt to the ground three times in its just over a century long existence as a Spanish settlement, first by French pirates in 1543, again on 27 May 1592 by a 110 strong landing party from a 4 ship English naval squadron led by Christopher Newport in his flagship Golden Dragon, who destroyed all 150 houses in the settlement and finally by the Spanish themselves in 1605, for reasons set out below.[10]

In 1595, the Spanish, frustrated by the twenty-year rebellion of their Dutch subjects, closed their home ports to rebel shipping from the Netherlands, cutting them off from the critical salt supplies necessary for their herring industry. The Dutch responded by sourcing new salt supplies from Spanish America where colonists were more than happy to trade. So large numbers of Dutch traders/pirates joined their English and French brethren trading on the remote coasts of Hispaniola. In 1605, Spain was infuriated that Spanish settlements on the northern and western coasts of the island persisted in carrying out large scale and illegal trade with the Dutch, who were at that time fighting a war of independence against Spain in Europe and the English, a very recent enemy state, and so decided to forcibly resettle their inhabitants closer to the city of Santo Domingo.[11] This action, known as the Devastaciones de Osorio, proved disastrous; more than half of the resettled colonists died of starvation or disease, over 100,000 cattle were abandoned and many slaves escaped.[12] Five of the existing thirteen settlements on the island were brutally razed by Spanish troops including the two settlements on the territory of present-day Haiti, La Yaguana and Bayaja. Many of the inhabitants fought, escaped to the jungle or fled to the safety of passing Dutch ships[13] This Spanish action was counterproductive as English, Dutch and French pirates were now free to establish bases on the island's abandoned northern and western coasts, where wild cattle were now plentiful and free.

Saint-Domingue

In the early seventeenth century, the Spanish government ordered the evacuation of the northern and western coast of the island and forcing the relocation to areas close to the city of Santo Domingo, to prevent the pirates from other European nations. This ended up being counterproductive to Spain, because in 1625 the pirates and French buccaneers began to establish settlements on the island of Tortuga and in a strip north of Hispaniola surrounding Port-de-Paix and were soon joined by like-minded English and Dutch privateers and pirates, who formed a lawless international community that survived by preying on Spanish ships and hunting wild cattle. Although the Spanish destroyed the buccaneers' settlements in 1629, 1635, 1638 and 1654, on each occasion they returned. In 1655, the newly established English administration on Jamaica sponsored the re-occupation of Tortuga under Elias Watts as governor. In 1660, the English made the mistake of replacing Watts as governor by a Frenchman Jeremie Deschamps,[14] on condition he defended English interests. Deschamps on taking control of the island proclaimed for the King of France, set up French colours, and defeated several English attempts to reclaim the island. It is from this point in 1660 that unbroken French rule in Haiti begins.[15] In 1663, Deschamps founded a French settlement Léogâne on the western coast of the island on the abandoned site of the former Spanish town of Yaguana.

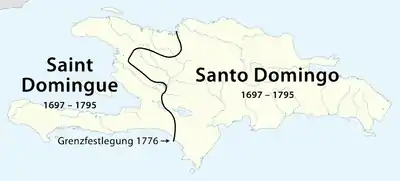

In 1664, the newly established French West India Company took control of the new colony and France formally claimed control of the western portion of the island of Hispaniola. In 1665, they established a French settlement on the mainland of Hispaniola opposite Tortuga at Port-de-Paix. In 1670, the headland of Cap-Français (now Cap-Haïtien), was settled further to the east along the northern coast. In 1676, the colonial capital was moved from Tortuga to Port-de-Paix. In 1684, the French and Spanish signed the Treaty of Ratisbon that included provisions to suppress the actions of the Caribbean privateers, which effectively ended the era of the buccaneers on Tortuga, many being employed by the French Crown to hunt down any of their former comrades who preferred to turn outright pirate.[16] Under the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain officially ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France which renamed the colony Saint-Domingue. By that time, planters outnumbered buccaneers and, with the encouragement of Louis XIV, they had begun to grow tobacco, indigo, cotton and cacao on the fertile northern plain, thus prompting the importation of African slaves.

In 1777, France and Spain signed a border treaty, in which the western and northwestern coast of Hispaniola would be French and the rest of the island would be Spanish. By 1780 Saint-Domingue was the richest colony in the world, even than all the British Thirteen Colonies and the West Indies together. The French established an economy based on the production and export of sugar sustained on the forced labor of black slaves imported from West and Central Africa. Slavery of blacks was characterized as one of the most ruthless in which terror and severe punishments were applied to slaves.[17]

By 1789, the Saint Dominican population was composed as follows:[18][19][20]

- 40,000 Grand-blancs (literally "Great whites" in French) and Petit-blancs ("Little whites")

- 28,000 Sang-melés (French for: "Mixed blood") or free people of color.

- 452,000 slaves

The white population were 8% of Saint-Domingue’s population, but they owned 70% of the wealth and 75% of the slaves in the colony. The mulatto population were 5% of the population and had the 30% of the wealth. The slaves were 87% of the population.[20]

Haitian Revolution

When the French Revolution started, the ideas of freedom among men spread in Saint-Domingue. Blacks and the majority African descendants such as Jean-Jacques Dessalines, rebelled against their white French masters. The rebels killed more than a thousand French people in 1791.[20] To preserve their lives, they fled Saint-Domingue. The wealthy grand-blancs returned to France or went to French Louisiana, but the petit-blancs who did not have many resources were compelled to move to the eastern side of Hispaniola, Cuba and Puerto Rico.[21] Notably, there were many sang-melés — some of which fled from Saint-Domingue — who settled in neighboring islands (mostly Puerto Rico and Cuba).

Most French colonists died or fled Saint-Domingue during the Haitian Revolution and the surviving remainder were either killed in the 1804 Haiti massacre or were thought to be of some use to the country's development, such as doctors, teachers and engineers. These colonists were considered valuable and were not to be harmed in any way.[22] Prior to the US occupation of 1915 it was hard for white foreigners to become Haitian citizens due to restrictions on owning land in Haiti. Exceptions were made for Germans, Poles and Frenchmen who had fought with the rebels against France in the war and their descendants. White foreigners could become citizens only by marrying Haitians.[23]

Origins

Before the Haitian Revolution, Haitians were categorized under three major categories: white, black and mulatto. But these were far more complex in practice, involving the coarseness of one's hair, nose measurements and assessments of other facial features.[24]

Demographics

Today, a group of Haitians are direct descendants of the Frenchmen who were saved from the massacre.[22] As of 2013, people of solely European descent are a small minority in Haiti. The combined population of whites and multiracial people constitutes 5% of the population, roughly half a million people.[25] People born to foreigners on Haitian soil are not automatically Haitian citizens due to the jus sanguinis (from Latin 'right of blood') principle of nationality law.[26] In addition to those of French descent, other White Haitians are of German, Polish, Italian, Spanish, English, Dutch, Irish and American descent. Most white Haitians live in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area, particularly the wealthy suburb of Pétion-Ville.[27]

According to the Haitian constitution since the time of independence, all citizens are to be referred to as black, where all races are considered equal to avoid prejudice.[28] The creole term nèg is derived from the French word negre (which means "black") and is used similarly to dude or guy in English.[24] A Haitian man is always a nèg, even if he is of European descent where he would be called a nèg blan ("white guy") and his counterpart being nèg nwa ("black guy"); all with no racist overtones.[1] Foreigners are always referred to as simply blan regardless of skin-tone, denoting a double meaning for the word.[2]

In the countryside, it is common to hear a poor light-skinned person called ti-wouj (little red), ti-blan (little white) or simply "blan" rather than a milat (mulatto), which is commonly being used to exclude individuals at the bottom of the social ladder as the term "mulatto" historically coincides with people who were more privileged.[29]

See also

References

- Warner, R. Stephen; Wittner, Judith G. (1998). Gatherings in Diaspora: Religious Communities and the New Immigration. Temple University. p. 155. ISBN 1566396131. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Katz, Jonathan M. (2013). The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. Macmillan. p. 56. ISBN 9780230341876. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "The Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803".

- Cooks, Carlos A. (21 October 1992). Carlos Cooks and Black Nationalism from Garvey to Malcolm. The Majority Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780912469287.

- Graves, Kerry A. (21 October 2023). Haiti. Capstone. p. 22. ISBN 9780736810784.

- "Fort-Liberté: A captivating Site". Haitian Treasures. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- Clammer, Paul; Michael Grosberg; Jens Porup (2008). Dominican Republic and Haiti. Lonely Planet. pp. 339, 330–333. ISBN 978-1-74104-292-4. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Population of Fort Liberté, Haiti". Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- [Haitian Revolution | Causes, Summary, & Facts Haitian Revolution | Causes, Summary, & Facts]

- Historic Cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia (2005). David Marley. Page 121

- Knight, Franklin, The Caribbean: The Genesis of a Fragmented Nationalism, 3rd ed. p. 54 New York, Oxford University Press 1990.

- Rough Guide to the Dominican Republic, p. 352.

- Peasants and Religion: A Socioeconomic Study of Dios Olivorio and the Palma Sola Movement in the Dominican Republic. Jan Lundius & Mats Lundah. Routledge 2000, p. 397.

- de Saint-Méry, Moreau (1797). Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l'isle Saint-Domingue (réédition, 3 volumes, Paris, Société française d'histoire d'outre-mer, 1984 ed.). pp. 667–670.

- The Buccaneers in the West Indies in the XVII Century

- Short History of Tortuga, 1625–1688

- Robert Hein, Written in Blood: The History of the Haitian People (University Press of America: Lantham, Md., 1996)

- Leyburn, James. El pueblo haitiano.

- James, C.L.R. "The Black Jacobins". p. 55.

- Dr. Mu-Kien Adriana Sang (1999). Dr. Mu-Kien Adriana Sang (ed.). Historia Dominicana: Ayer y Hoy (in Spanish). SUSAETA Ediciones Dominicanas. pp. 78–79, 81.

- French colonization in Cuba, 1791–1809

- David Ritter (2010). Forgotten faces of Haiti (Part 1). Haiti: Carib Productions. Event occurs at 06:30. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- Girard 2011 pg 340

- Averill, Gabe (1997). A Day for the Hunter, a Day for the Prey: Popular Music and Power in Haiti. University of Chicago Press. p. 5. ISBN 0226032914. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "CIA – The World Factbook – Haiti". CIA. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- Paraison, Edwin (9 May 2009). "Doble nacionalidad; La Constitución haitiana en la diáspora" (in Spanish). Hoy. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Dubois 2012 pgs 142-43

- Zéphir, Flore (1996). Haitian Immigrants in Black America: A Sociological and Sociolinguistic Portrait. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-89789-451-0.

- Gregory, Steven (1996). Race. Rutgers University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0813521092. Retrieved 9 June 2015.