Great Divergence

The Great Divergence or European miracle is the socioeconomic shift in which the Western world (i.e. Western Europe and the parts of the New World where its people became the dominant populations) overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilizations, eclipsing previously dominant or comparable civilizations from the Middle East and Asia such as the Ottoman Empire, Mughal India, Safavid Iran, Qing China and Tokugawa Japan, among others.[2]

Scholars have proposed a wide variety of theories to explain why the Great Divergence happened, including geography, culture, institutions, colonialism, resources and pure chance.[3] There is disagreement over the nomenclature of the "great" divergence, as a clear point of beginning of a divergence is traditionally held to be the 16th or even the 15th century, with the commercial revolution and the origins of mercantilism and capitalism during the Renaissance and the Age of Discovery, the rise of the European colonial empires, proto-globalization, the Scientific Revolution, or the Age of Enlightenment.[4][5][6][7] Yet the largest jump in the divergence happened in the late 18th and 19th centuries with the Industrial Revolution and Technological Revolution. For this reason, the "California school" considers only this to be the great divergence.[8][9][10][11]

Technological advances, in areas such as transportation, mining, and agriculture, were embraced to a higher degree in western Eurasia than the east during the Great Divergence. Technology led to increased industrialization and economic complexity in the areas of agriculture, trade, fuel and resources, further separating east and west. Western Europe's use of coal as an energy substitute for wood in the mid-19th century gave it a major head start in modern energy production. In the twentieth century, the Great Divergence peaked before the First World War and continued until the early 1970s; then, after two decades of indeterminate fluctuations, in the late 1980s it was replaced by the Great Convergence as the majority of developing countries reached economic growth rates significantly higher than those in most developed countries.[12]

Terminology and definition

The term "Great Divergence" was coined by Samuel P. Huntington[13] in 1996 and used by Kenneth Pomeranz in his book The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (2000). The same phenomenon was discussed by Eric Jones, whose 1981 book The European Miracle: Environments, Economies and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia popularized the alternate term "European Miracle".[14] Broadly, both terms signify a socioeconomic shift in which European countries advanced ahead of others during the modern period.[15]

The timing of the Great Divergence is in dispute among historians. The traditional dating is as early as the 16th (or even 15th[16]) century, with scholars arguing that Europe had been on a trajectory of higher growth since that date.[17] Pomeranz and others of the California school argue that the period of most rapid divergence was during the 19th century.[8][9] Citing nutrition data and chronic European trade deficits as evidence, these scholars argue that before that date the most developed parts of Asia, in terms of grain wage had comparable economic development to Europe, especially Qing China in the Yangzi Delta[18][9] and South Asia in the Bengal Subah.[19][20][21] Economic Historians Prasannan Parthasarathi and Jeffrey G. Williamson also argue citing the earnings data from primary sources show that until mid-late 18th-century real wages and living standards in Bengal sultanate (under the Nawabs of Bengal) a South Indian Kingdom of Mysore and Maratha Confederacy were on par if not higher than in Britain, which in turn had the highest living standards in Europe.[19][22]

Some argue that the cultural factors behind the divergence can be traced to earlier periods and institutions such as the Renaissance and the Chinese imperial examination system.[23][24] Broadberry asserts that in terms of Silver wage even the richest areas of Asia were behind Western Europe as early as the 16th century. He cites statistics comparing England to the Yangzi Delta (the most developed part of China by a good margin) showing that by 1600 the former had three times the latter's average wages when measured in silver, 15% greater wages when measured in wheat equivalent (the latter being used as a proxy for buying power of basic subsistence goods and the former as a proxy for buying power of craft goods, especially traded ones), and higher urbanization.[25] England's silver wages were also five times higher than those of India in the late 16th century, with relatively higher grain wages reflecting an abundance of grain, and low silver wages reflecting low levels of overall development. Grain wages started to diverge more sharply from the early 18th century, with English wages being two and a half times higher than India or China's in wheat equivalent while remaining about five times higher in silver at that time.[26] However this would only apply to Northwest Europe, as Broadberry states that the silver wages in Southern, Central, and Eastern Europe were still on par with the advanced parts of Asia until 1800[27]

The question of whether grain or silver wages more accurately reflect the overall Standard of living has been long debated by Economists and Historians.

Conditions in pre–Great Divergence cores

"Why do the Christian nations, which were so weak in the past compared with Muslim nations begin to dominate so many lands in modern times and even defeat the once victorious Ottoman armies?"..."Because they have laws and rules invented by reason."

Ibrahim Muteferrika, Rational basis for the Politics of Nations (1731)[28]

Although core regions in Eurasia had achieved a relatively high standard of living by the 18th century, shortages of land, soil degradation, deforestation, lack of dependable energy sources, and other ecological constraints limited growth in per capita incomes.[29] Rapid rates of depreciation on capital meant that a great part of savings in pre-modern economies were spent on replacing depleted capital, hampering capital accumulation.[30] Massive windfalls of fuel, land, food and other resources were necessary for continued growth and capital accumulation, leading to colonialism.[31] The Industrial Revolution overcame these restraints, allowing rapid, sustained growth in per capita incomes for the first time in human history.

Western Europe

After the Viking, Muslim, and Magyar invasions waned in the 10th century, Western Christian Europe entered a period of prosperity, population growth and territorial expansion known as the High Middle Ages. Trade and commerce revived, with increased specialization between areas and between the countryside and artisans in towns. By the 13th century, the best land had been occupied and agricultural income began to fall, though trade and commerce continued to expand, especially in Venice and other northern Italian cities. The 14th century, then, brought a series of calamities: famines, wars, the Black Death and other epidemics.

The Historical Origins of Economic Growth suppose that the Black Death had some moments that might have positively affected development. The labor scarcity that resulted from the Black Death led women to enter the workforce and drove active markets for agricultural labor.[32] The resulting drop in the population led to falling rents and rising wages, undermining the feudal and manorial relationships that had characterized Medieval Europe.[33]

According to a 2014 study, "there was a 'little divergence' within Europe between 1300 and 1800: real wages in the North Sea Region more or less stabilized at the level attained after the Black Death, and remained relatively high (above subsistence) throughout the early modern period (and into the nineteenth century), whereas real wages in the 'periphery' (in Germany, Italy, and Spain) began to fall after the fifteenth century and returned to some kind of subsistence minimum during the 1500–1800 period. This 'little divergence' in real wages mirrors a similar divergence in GDP per capita: in the 'periphery' of Europe there was almost no per capita growth (or even a decline) between 1500 and 1800, whereas in Holland and England real income continued to rise and more or less doubled in this period".[34]

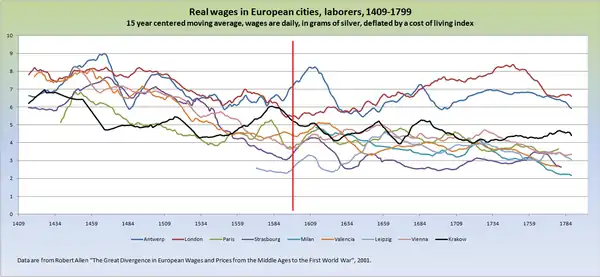

In the Age of Discovery, navigators discovered new routes to the Americas and Asia. Commerce expanded, together with innovations such as joint stock companies and various financial institutions. New military technologies favored larger units, leading to a concentration of power in states whose finances relied on trade. The Dutch Republic was controlled by merchants, while Parliament gained control of the Kingdom of England after a long struggle culminating in the Glorious Revolution. These arrangements proved more hospitable to economic development.[35] At the end of the 16th century, London and Antwerp began pulling away from other European cities, as illustrated in the following graph of real wages in several European cities:[36]

According to a 2021 review of existing evidence by Jack Goldstone, the Great Divergence only arose after 1750 (or even 1800) in northwestern Europe. Prior to that, economic growth rates in northwestern Europe were neither sustained nor remarkable, and income per capita was similar to "peak levels achieved hundreds of years earlier in the most developed regions of Italy and China."[37]

The West had a series of unique advantages compared to Asia, such as the proximity of coal mines; the discovery of the New World, which alleviated ecological restraints on economic growth (land shortages etc.); and the profits from colonization.[38]

China

China has had a larger population than Europe throughout the last two millennia.[39] Unlike Europe, it was politically united for long periods during that time.

During the Song dynasty (960–1279), the country experienced a revolution in agriculture, water transport, finance, urbanization, science and technology, which made the Chinese economy the most advanced in the world from about 1100.[40][41] Mastery of wet-field rice cultivation opened up the hitherto underdeveloped south of the country, while later northern China was devastated by Jurchen and Mongol invasions, floods and epidemics. The result was a dramatic shift in the center of population and industry from the home of Chinese civilization around the Yellow River to the south of the country, a trend only partially reversed by the re-population of the north from the 15th century.[42] By 1300, China as a whole had fallen behind Italy in living standards and by 1400, England had also caught up with it but its wealthiest regions, especially the Yangzi Delta, may have remained on par with those of Europe until the early 18th century.[41][43]

In the late imperial period (1368–1911), comprising the Ming and Qing dynasties, taxation was low, and the economy and population grew significantly, though without substantial increases in productivity.[44] Chinese goods such as silk, tea, and ceramics were in great demand in Europe, leading to an inflow of silver, expanding the money supply and facilitating the growth of competitive and stable markets.[45] By the end of the 18th century, population density levels exceeded those in Europe.[46] China had more large cities but far fewer small ones than in contemporary Europe.[47][48] Kenneth Pomeranz originally claimed that Great Divergence did not begin until the 19th century.[8][9][10] Later he revisited his position and now sees the date between 1700 and 1750.[49][50]

India

According to a 2020 study and dataset, the Great Divergence between northern India (from Gujarat to Bengal) and Britain began in the late 17th century. It widened after the 1720s and exploded after the 1800s.[52] The study found that it was "primarily England's spurt and India's stagnation in the first half of the nineteenth century that brought about most serious differences in the standard of living."[53]

Throughout its history, India, especially the Bengal Sultanate, has been a major trading nation[54] that benefited from extensive external and internal trade. Its agriculture was highly efficient as well as its industry. Unlike China, Japan and western and central Europe, India did not experience extensive deforestation until the 19th and 20th centuries. It thus had no pressure to move to coal as a source of energy.[55] From the 17th century, cotton textiles from Mughal India became popular in Europe, with some governments banning them to protect their wool industries.[56] Mughal Bengal, the most developed region, in particular, was globally prominent in industries such as textile manufacturing and shipbuilding.[57]

In early modern Europe, there was significant demand for products from Mughal India, particularly in cotton textiles, as well as goods such as spices, peppers, indigo, silks, and saltpeter (for use in munitions).[58] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Indian textiles and silks. In the 17th and 18th centuries, India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia.[59] Amiya Kumar Bagchi estimates 10.3% of Bihar's populace were involved in hand spinning thread, 2.3% weaving, and 9% in other manufacturing trades, in 1809–13, to satisfy this demand.[60][61] In contrast, there was very little demand for European goods in India, which was largely self-sufficient, thus Europeans had very little to offer, except for some woolen textiles, unprocessed metals and a few luxury items. The trade imbalance caused Europeans to export large quantities of gold and silver to India in order to pay for Indian imports.[58]

Middle East

The Middle East was more advanced than Western Europe in 1000, on par by the middle of the 16th century, but by 1750, leading Middle Eastern states had fallen behind the leading Western European states of Britain and the Netherlands.[62][63]

An example of a Middle Eastern country that had an advanced economy in the early 19th century was Ottoman Egypt, which had a highly productive industrial manufacturing sector, and per-capita income that was comparable to leading Western European countries such as France and higher than that of Japan and Eastern Europe.[64] Other parts of the Ottoman Empire, particularly Syria and southeastern Anatolia, also had a highly productive manufacturing sector that was evolving in the 19th century.[65] In 1819, Egypt under Muhammad Ali began programs of state-sponsored industrialization, which included setting up factories for weapons production, an iron foundry, large-scale cotton cultivation, mills for ginning, spinning and weaving of cotton, and enterprises for agricultural processing. By the early 1830s, Egypt had 30 cotton mills, employing about 30,000 workers.[66] In the early 19th century, Egypt had the world's fifth most productive cotton industry, in terms of the number of spindles per capita.[67] The industry was initially driven by machinery that relied on traditional energy sources, such as animal power, water wheels, and windmills, which were also the principle energy sources in Western Europe up until around 1870.[68] While steam power had been experimented with in Ottoman Egypt by engineer Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma'ruf in 1551, when he invented a steam jack driven by a rudimentary steam turbine,[69] it was under Muhammad Ali of Egypt in the early 19th century that steam engines were introduced to Egyptian industrial manufacturing.[68] Boilers were manufactured and installed in Egyptian industries such as ironworks, textile manufacturing, paper mills, and hulling mills. Compared to Western Europe, Egypt also had superior agriculture and an efficient transport network through the Nile. Economic historian Jean Batou argues that the necessary economic conditions for rapid industrialization existed in Egypt during the 1820s–1830s.[68]

After the death of Muhammad Ali in 1849, his industrialization programs fell into decline, after which, according to historian Zachary Lockman, "Egypt was well on its way to full integration into a European-dominated world market as supplier of a single raw material, cotton." Lockman argues that, had Egypt succeeded in its industrialization programs, "it might have shared with Japan [or the United States] the distinction of achieving autonomous capitalist development and preserving its independence."[66]

Japan

Japanese society was governed by the Tokugawa Shogunate, which divided Japanese society into a strict hierarchy and intervened considerably in the economy through state monopolies[70] and restrictions on foreign trade; however, in practice, the Shogunate's rule was often circumvented.[71] From 725 to 1974, Japan experienced GDP per capita growth at an annual rate of 0.04%, with major periods of positive per capita GDP growth occurring during 1150–1280, 1450–1600 and after 1730.[72] There were no significant periods of sustained growth reversals.[72] Relative to the United Kingdom, GDP per capita was at roughly similar levels until the middle of the 17th century.[7][73] By 1850, per capita incomes in Japan were approximately a quarter of the British level.[7] However, 18th-century Japan had a higher life expectancy, 41.1 years for adult males, compared with 31.6 to 34 for England, between 27.5 and 30 for France, and 24.7 for Prussia.[74]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Pre-colonial sub-Saharan Africa was politically fragmented, just as early modern Europe was.[75] Africa was home to numerous wealthy empires which grew around coastal areas or large rivers that served as part of important trade routes. Africa was however far more sparsely populated than Europe.[75] According to University of Michigan political scientist Mark Dincecco, "the high land/ labor ratio may have made it less likely that historical institutional centralization at the "national level" would occur in sub-Saharan Africa, thwarting further state development."[75] The transatlantic slave trade may have further weakened state power in Africa.[75]

A series of states developed in the Sahel on the southern edge of the Sahara which made immense profits from trading across the Sahara, trading heavily in gold and slaves for the trans-Saharan slave trade. Kingdoms in the heavily forested regions of West Africa were also part of trade networks. The growth of trade in this area was driven by the Yoruba civilization, which was supported by cities surrounded by farmed land and made wealthy by extensive trade development.

For most of the first millennium AD, the Axumite Kingdom in East Africa had a powerful navy and trading links reaching as far as the Byzantine Empire and India. Between the 14th and 17th centuries, the Ajuran Sultanate in modern-day Somalia practiced hydraulic engineering and developed new systems for agriculture and taxation, which continued to be used in parts of the Horn of Africa as late as the 19th century.

On the east coast of Africa, Swahili kingdoms had a prosperous trading empire. Swahili cities were important trading ports along the Indian Ocean, engaging in trade with the Middle East and Far East.[76] Kingdoms in southeast Africa also developed extensive trade links with other civilizations as far away as China and India.[77] The institutional framework for long-distance trade across political and cultural boundaries had long been strengthened by the adoption of Islam as a cultural and moral foundation for trust among and with traders.[78]

Possible factors

Scholars have proposed numerous theories to explain why the Great Divergence occurred.

Coal

In metallurgy and steam engines the Industrial Revolution made extensive use of coal and coke – as cheaper, more plentiful and more efficient than wood and charcoal. Coal-fired steam engines also operated in the railways and in shipping, revolutionizing transport in the early 19th century. Kenneth Pomeranz drew attention to differences in the availability of coal between West and East. Due to regional climate, European coal mines were wetter, and deep mines did not become practical until the introduction of the Newcomen steam engine to pump out groundwater. In mines in the arid northwest of China, ventilation to prevent explosions was much more difficult.[79]

Another difference involved geographic distance; although China and Europe had comparable mining technologies, the distances between the economically developed regions and coal deposits differed vastly. The largest coal deposits in China are located in the northwest, within reach of the Chinese industrial core during the Northern Song (960–1127). During the 11th century China developed sophisticated technologies to extract and use coal for energy, leading to soaring iron production.[9] The southward population shift between the 12th and 14th centuries resulted in new centers of Chinese industry far from the major coal deposits. Some small coal deposits were available locally, though their use was sometimes hampered by government regulations. In contrast, Britain contained some of the largest coal deposits in Europe[80] – all within a relatively compact island.

The centrality of coal to Industrial revolution was criticized by Gregory Clark and David Jacks, who show that coal could be substituted without much loss of national income.[81] Similarly Deirdre N. McCloskey says that coal could easily have been imported to Britain from other countries. Moreover, the Chinese could move their industries closer to coal reserves.[82]

New World

A variety of theories posit Europe's unique relationship with the New World as a major cause of the Great Divergence. The high profits earned from the colonies and the slave trade constituted 7 percent a year, a relatively high rate of return considering the high rate of depreciation on pre-industrial capital stocks, which limited the amount of savings and capital accumulation.[30] Early European colonization was sustained by profits through selling New World goods to Asia, especially silver to China.[83] According to Pomeranz, the most important advantage for Europe was the vast amount of fertile, uncultivated land in the Americas which could be used to grow large quantities of farm products required to sustain European economic growth and allowed labor and land to be freed up in Europe for industrialization.[84] New World exports of wood, cotton, and wool are estimated to have saved England the need for 23 to 25 million acres (100,000 km2) of cultivated land (by comparison, the total amount of cultivated land in England was just 17 million acres), freeing up immense amounts of resources. The New World also served as a market for European manufactures.[85]

Chen (2012) also suggested that the New World as a necessary factor for industrialization, and trade as a supporting factor causing less developed areas to concentrate on agriculture supporting industrialized regions in Europe.[24]

Political fragmentation

Jared Diamond and Peter Watson argue that a notable feature of Europe's geography was that it encouraged political balkanization, such as having several large peninsulas[86] and natural barriers such as mountains and straits that provided defensible borders. By contrast, China's geography encouraged political unity, with a much smoother coastline and a heartland dominated by two river valleys (Yellow and Yangtze).

Thanks to the topographical structure with "its mountain chains, coasts, and major marches , formed boundaries at which states expanding from the core areas could meet and pause…".[32] Hence, this helps European countries feel "in the same boat". Due to the location of mountain ranges, there were several distinct geographical cores that could provide the nuclei for future states.[32] Another point in Europe’s political fragmentation in comparison to, for example, China is the location of the Eurasian steppe. After horse domestication, steppe nomads (for instance, Genghis Khan and the Mongols) posed a threat to the sedentary population until the 18th century. The reason for the threat is "the fragile ecology of the steppe meant that during periods of drought or cold weather, steppe nomads were more likely to invade neighboring populations".[87] Hence, this stimulated China, which is near the steppe, to build a strong, unified state.[88]

In his book Guns, Germs, and Steel, Diamond argues that advanced cultures outside Europe had developed in areas whose geography was conducive to large, monolithic, isolated empires. In these conditions policies of technological and social stagnation could persist. He gives the example of China in 1432, when the Xuande Emperor outlawed the building of ocean-going ships, in which China was the world leader at the time. On the other hand, Christopher Columbus obtained sponsorship from Queen Isabella I of Castile for his expedition even though three other European rulers turned it down. As a result, governments that suppressed economic and technological progress soon corrected their mistakes or were out-competed relatively quickly. He argues that these factors created the conditions for more rapid internal superpower change (Spain succeeded by France and then by the United Kingdom) than was possible elsewhere in Eurasia.

Justin Yifu Lin argued that China's large population size proved beneficial in technological advancements prior to the 14th century, but that the large population size was not an important factor in the kind of technological advancements that resulted in the Industrial Revolution.[89] Early technological advancements depended on "learning by doing" (where population size was an important factor, as advances could spread over a large political unit), whereas the Industrial Revolution was the result of experimentation and theory (where population size is less important).[89] Before Europe took some steps towards technology and trade, there was an issue with the importance of education. By 1800, literacy rates were 68% in the Netherlands and 50% in Britain and Belgium, whereas in non-European societies, literacy rates started to rise in the 20th century. At the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, there was no demand for skilled labor. However, during the next phases of the Industrial Revolution, factors that influence worker productivity—education, training, skills, and health—were the primary purpose.[90]

Economic historian Joel Mokyr has argued that political fragmentation (the presence of a large number of European states) made it possible for heterodox ideas to thrive, as entrepreneurs, innovators, ideologues and heretics could easily flee to a neighboring state in the event that the one state would try to suppress their ideas and activities. This is what set Europe apart from the technologically advanced, large unitary empires such as China. China had both a printing press and movable type, yet the industrial revolution would occur in Europe. In Europe, political fragmentation was coupled with an "integrated market for ideas" where Europe's intellectuals used the lingua franca of Latin, had a shared intellectual basis in Europe's classical heritage and the pan-European institution of the Republic of Letters.[91] The historian Niall Ferguson attributes this divergence to the West's development of six "killer apps", which he finds were largely missing elsewhere in the world in 1500 – "competition, the scientific method, the rule of law, modern medicine, consumerism and the work ethic".[92]

Economic historian Tuan-Hwee Sng has argued that the large size of the Chinese state contributed to its relative decline in the 19th century:[93]

The vast size of the Chinese empire created a severe principal–agent problem and constrained how the country was governed. In particular, taxes had to be kept low due to the emperor's weak oversight of his agents and the need to keep corruption in check. The Chinese state's fiscal weaknesses were long masked by its huge tax base. However, economic and demographic expansion in the eighteenth century exacerbated the problems of administrative control. This put a further squeeze on the nation's finances and left China ill-prepared for the challenges of the nineteenth century.

One reason why Japan was able to modernize and adopt the technologies of the West was due to its much smaller size relative to China.[94]

Stanford political scientist Gary W. Cox argues in a 2017 study,[95]

that Europe's political fragmentation interacted with her institutional innovations to foster substantial areas of "economic liberty," where European merchants could organize production freer of central regulation, faced fewer central restrictions on their shipping and pricing decisions, and paid lower tariffs and tolls than their counterparts elsewhere in Eurasia. When fragmentation afforded merchants multiple politically independent routes on which to ship their goods, European rulers refrained from imposing onerous regulations and levying arbitrary tolls, lest they lose mercantile traffic to competing realms. Fragmented control of trade routes magnified the spillover effects of political reforms. If parliament curbed arbitrary regulations and tolls in one realm, then neighboring rulers might have to respond in kind, even if they themselves remained without a parliament. Greater economic liberty, fostered by the interaction of fragmentation and reform, unleashed faster and more inter-connected urban growth.

Other geographic factors

Fernand Braudel of the Annales school of historians argued that the Mediterranean Sea was poor for fishing due to its depth, therefore encouraging long-distance trade.[96] Furthermore, the Alps and other parts of the Alpide belt supplied the coastal regions with fresh migrants from the uplands.[96] This helped the spread of ideas, as did the east–west axis of the Mediterranean which lined up with the prevailing winds and its many archipelagos which together aided navigation, as was also done by the great rivers which brought inland access, all of which further increased immigration.[86] The peninsulas of the Mediterranean also promoted political nationalism which brought international competition.[86] One of the geographical issues that affected the economies of Europe and the Middle East is the discovery of the Americas and the Cape Route around Africa.[32] The old trade routes became useless, which led to the economic decline of cities both in Central Asia and the Middle East and, moreover, in Italy.[97]

Testing theories related to geographic endowments economists William Easterly and Ross Levine find evidence that tropics, germs, and crops affect development through institutions. They find no evidence that tropics, germs, and crops affect country incomes directly other than through institutions, nor did they find any effect of policies on development once controls for institutions were implemented.[98] However, there is the opposite argument to the abovementioned statement. In the 16th century in Ireland, potato cultivation became popular as this crop was perfectly suited to the Irish soil and climate. Hence, it raised farmers' incomes in the short run, and the peasants' quality of life rose with the increase in their calorie consumption. The majority of the population was dependent on potatoes. In the 19th century, a new fungus, late blight, was ravaging potato crops in the U.S. and then Europe. In 1845, half of the potatoes were blighted; in 1845, three-quarters were. The result was the Great Famine (1845–1849).[32]

Innovation

Beginning in the early 19th century, economic prosperity rose greatly in the West due to improvements in technological efficiency,[99] as evidenced by the advent of new conveniences including the railroad, steamboat, steam engine, and the use of coal as a fuel source. These innovations contributed to the Great Divergence, elevating Europe and the United States to high economic standing relative to the East.[99]

It has been argued the attitude of the East towards innovation is one of the other factors that might have played a big role in the West's advancements over the East. According to David Landes, after a few centuries of innovations and inventions, it seemed like the East stopped trying to innovate and began to sustain what they had. They kept nurturing their pre-modern inventions and did not move forward with the modern times. China decided to continue a self-sustaining process of scientific and technological advancement on the basis of their indigenous traditions and achievements.[100] The East's attitude towards innovation showed that they focused more on experience, while the West focused on experimentation. The East did not see the need to improve on their inventions and thus from experience, focused on their past successes. While they did this, the West was focused more on experimentation and trial by error, which led them to come up with new and different ways to improve on existing innovations and create new ones.[101]

Efficiency of markets and state intervention

A common argument is that Europe had more free and efficient markets than other civilizations, which has been cited as a reason for the Great Divergence.[102] In Europe, market efficiency was disrupted by the prevalence of feudalism and mercantilism. Practices such as entail, which restricted land ownership, hampered the free flow of labor and buying and selling of land. These feudal restrictions on land ownership were especially strong in continental Europe. China had a relatively more liberal land market, hampered only by weak customary traditions.[103] Bound labor, such as serfdom and slavery were more prevalent in Europe than in China, even during the Manchu conquest.[104] Urban industry in the West was more restrained by guilds and state-enforced monopolies than in China, where in the 18th century the principal monopolies governed salt and foreign trade through Guangzhou.[105] Pomeranz rejects the view that market institutions were the cause of the Great Divergence, and concludes that China was closer to the ideal of a market economy than Europe.[103]

Economic historian Paul Bairoch presents a contrary argument, that Western countries such as the United States, Britain and Spain did not initially have free trade, but had protectionist policies in the early 19th century, as did China and Japan. In contrast, he cites the Ottoman Empire as an example of a state that did have free trade, which he argues had a negative economic impact and contributed to its deindustrialization. The Ottoman Empire had a liberal trade policy, open to foreign imports, which has origins in capitulations of the Ottoman Empire, dating back to the first commercial treaties signed with France in 1536 and taken further with capitulations in 1673 and 1740, which lowered duties to only 3% for imports and exports. The liberal Ottoman policies were praised by British economists advocating free trade, such as J. R. McCulloch in his Dictionary of Commerce (1834), but later criticized by British politicians opposing free trade, such as prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, who cited the Ottoman Empire as "an instance of the injury done by unrestrained competition" in the 1846 Corn Laws debate:[106]

There has been free trade in Turkey, and what has it produced? It has destroyed some of the finest manufactures of the world. As late as 1812 these manufactures existed; but they have been destroyed. That was the consequences of competition in Turkey, and its effects have been as pernicious as the effects of the contrary principle in Spain.

Wages and living standards

Classical economists, beginning with Adam Smith and Thomas Malthus, argued that high wages in the West stimulated labor-saving technological advancements.[107][108]

Revisionist studies in the mid to late 20th century have depicted living standards in 18th century China and pre-Industrial Revolution Europe as comparable.[9][109] According to Pomeranz life expectancy in China and Japan was comparable to the advanced parts of Europe.[74] Similarly Chinese consumption per capita in calories intake is comparable to England.[110] According to Pomeranz and others, there was modest per capita growth in both regions,[111] the Chinese economy was not stagnant, and in many areas, especially agriculture, was ahead of Western Europe.[112] Chinese cities were also ahead in public health.[113] Economic historian Paul Bairoch estimated that China's GNP per capita in 1800 was $228 in 1960 US dollars ($1,007 in 1990 dollars), higher than Western Europe's $213 ($941 in 1990 dollars) at the time.[114]

Similarly for Ottoman Egypt, its per-capita income in 1800 was comparable to that of leading Western European countries such as France, and higher than the overall average income of Europe and Japan.[64] Economic historian Jean Barou estimated that, in terms of 1960 dollars, Egypt in 1800 had a per-capita income of $232 ($1,025 in 1990 dollars). In comparison, per-capita income in terms of 1960 dollars for France in 1800 was $240 ($1,060 in 1990 dollars), for Eastern Europe in 1800 was $177 ($782 in 1990 dollars), and for Japan in 1800 was $180 ($795 in 1990 dollars).[115][116]

According to Paul Bairoch, in the mid-18th century, "the average standard of living in Europe was a little bit lower than that of the rest of the world."[21] He estimated that, in 1750, the average GNP per capita in the Eastern world (particularly China, India and the Middle East) was $188 in 1960 dollars ($830 in 1990 dollars), higher than the West's $182 ($804 in 1990 dollars).[117] He argues that it was after 1800 that Western European per-capita income pulled ahead.[118] However, the average incomes of China[114] and Egypt[115] were still higher than the overall average income of Europe.[114][115]

According to Jan Luiten van Zanden, the relationship between GDP per capita with wages and standards of living is very complex. He gives Netherlands economic history as an example. Real wages in Netherlands declined during the early modern period between 1450 and 1800. The decline was fastest between 1450/75 and the middle of the sixteenth century, after which real wages stabilized, meaning that even during the Dutch Golden Age purchasing power did not grow. The stability remained until the middle of 18th century, after which wages declined again. Similarly citing studies of the average height of Dutch men, van Zaden shows that it declined from the Late Middle Ages. During 17th and 18th centuries, at the height of Dutch Golden Age, the average height was 166 centimeters, about 4 centimeters lower than in 14th and early 15th century. This most likely indicates consumption declines during the early modern period, and average height would not equal medieval heights until the 20th century. Meanwhile, GDP per capita increased by 35 to 55% between 1510/1514 and the 1820s. Hence it is possible that standards of living in advanced parts of Asia were comparable with Western Europe in the late 18th century, while Asian GDP per capita was about 70% lower.[20]

Şevket Pamuk and Jan-Luiten van Zanden also show that during the Industrial Revolution, living standards in Western Europe increased little before the 1870s, as the increase in nominal wages was undermined by rising food prices. The substantial rise in living standards only started after 1870, with the arrival of cheap food from the Americas. Western European GDP grew rapidly after 1820, but real wages and the standard of living lagged behind.[119]

According to Robert Allen, at the end of the Middle Ages, real wages were similar across Europe and at a very high level. In the 16th and 17th century wages collapsed everywhere, except in the Low Countries and London. These were the most dynamic regions of the early modern economy, and their living standards returned to the high level of the late fifteenth century. The dynamism of London spread to the rest of England in 18th century. Although there was fluctuation in real wages in England between 1500 and 1850, there was no long term rise until the last third of 19th century. And it was only after 1870 that real wages begin to rise in other cities of Europe, and only then they finally surpassed the level of late 15th century. Hence while the Industrial Revolution raised GDP per capita, it was only a century later before a substantial raise in standard of living.[120]

However, responding to the work of Bairoch, Pomeranz, Parthasarathi and others, more subsequent research has found that parts of 18th century Western Europe did have higher wages and levels of per capita income than in much of India, Ottoman Turkey, Japan and China. However, the views of Adam Smith were found to have overgeneralized Chinese poverty.[121][122][123][124][125][126][127] Between 1725 and 1825 laborers in Beijing and Delhi were only able to purchase a basket of goods at a subsistence level, while laborers in London and Amsterdam were able to purchase goods at between 4 and 6 times a subsistence level.[128] As early as 1600 Indian GDP per capita was about 60% the British level. A real decline in per capita income did occur in both China and India, but in India began during the Mughal period, before British colonialism. Outside of Europe much of this decline and stagnation has been attributed to population growth in rural areas outstripping growth in cultivated land as well as internal political turmoil.[124][121] Free colonials in British North America were considered by historians and economists in a survey of academics to be amongst the most well off people in the world on the eve of the American Revolution.[129] The earliest evidence of a major health transition leading to increased life expectancy began in Europe in the 1770s, approximately one century before Asia's.[130] Robert Allen argues that the relatively high wages in eighteenth century Britain both encouraged the adoption of labour-saving technology and worker training and education, leading to industrialisation.[131]

Luxury consumption

Luxury consumption is regarded by many scholars to have stimulated the development of capitalism and thus contributed to the Great Divergence.[132] Proponents of this view argue that workshops, which manufactured luxury articles for the wealthy, gradually amassed capital to expand their production and then emerged as large firms producing for a mass market; they believe that Western Europe's unique tastes for luxury stimulated this development further than other cultures. However, others counter that luxury workshops were not unique to Europe; large cities in China and Japan also possessed many luxury workshops for the wealthy,[133] and that luxury workshops do not necessarily stimulate the development of "capitalistic firms".[134]

Property rights

Differences in property rights have been cited as a possible cause of the Great Divergence.[135][136] This view states that Asian merchants could not develop and accumulate capital because of the risk of state expropriation and claims from fellow kinsmen, which made property rights very insecure compared to those of Europe.[137] However, others counter that many European merchants were de facto expropriated through defaults on government debt, and that the threat of expropriation by Asian states was not much greater than in Europe, except in Japan.[138]

Government and policies are seen as an integral part of modern societies and have played a major role in how different economies have been formed. The Eastern societies had governments which were controlled by the ruling dynasties and thus, were not a separate entity. Their governments at the time lacked policies that fostered innovation and thus resulted in slow advancements. As explained by Cohen, the east had a restrictive system of trade that went against the free world market theory; there was no political liberty or policies that encouraged the capitalist market (Cohen, 1993). This was in contrast to the western society that developed commercial laws and property rights which allowed for the protection and liberty of the marketplace. Their capitalist ideals and market structures encouraged innovation.[139][89][140][141]

Pomeranz (2000) argues that much of the land market in China was free, with many supposedly hereditary tenants and landlords being frequently removed or forced to sell their land. Although Chinese customary law specified that people within the village were to be offered the land first, Pomeranz states that most of the time the land was offered to more capable outsiders, and argues that China actually had a freer land market than Europe.[103]

However, Robert Brenner and Chris Isett emphasize differences in land tenancy rights. They argue that in the lower Yangtze, most farmers either owned land or held secure tenancy at fixed rates of rent, so that neither farmers nor landlords were exposed to competition. In 15th century England, lords had lost their serfs, but were able to assert control over almost all of the land, creating a rental market for tenant farmers. This created competitive pressures against subdividing plots, and the fact that plots could not be directly passed on to sons forced them to delay marriage until they had accumulated their own possessions. Thus in England both agricultural productivity and population growth were subject to market pressures throughout the early modern period.[142]

A 2017 study found that the presence of secure property rights in Europe and their absence in large parts of the Middle-East contributed to the increase of expensive labour-saving capital goods, such as water-mills, windmills, and cranes, in medieval Europe and their decrease in the Middle-East.[143]

High-level equilibrium trap

The high-level equilibrium trap theory argues that China did not undergo an indigenous industrial revolution since its economy was in a stable equilibrium, where supply and demand for labor were equal, disincentivizing the development of labor-saving capital.

European colonialism

A number of economic historians have argued that European colonialism played a major role in the deindustrialization of non-Western societies. Paul Bairoch, for example, cites British colonialism in India as a primary example, but also argues that European colonialism played a major role in the deindustrialization of other countries in Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America, and contributed to a sharp economic decline in Africa.[144] Other modern economic historians have blamed British colonial rule for India's deindustrialization in particular.[145][146][147][148] The colonization of India is seen as a major factor behind both India's deindustrialization and Britain's Industrial Revolution.[146][147][148]

The historian Jeffrey G. Williamson has argued that India went through a period of deindustrialization in the latter half of the 18th century as an indirect outcome of the collapse of the Mughal Empire, with British rule later causing further deindustrialization.[60] According to Williamson, the decline of the Mughal Empire led to a decline in agricultural productivity, which drove up food prices, then nominal wages, and then textile prices, which led to India losing a share of the world textile market to Britain even before it had superior factory technology,[149] though Indian textiles still maintained a competitive advantage over British textiles up until the 19th century.[150] Economic historian Prasannan Parthasarathi, however, has argued that there wasn't any such economic decline for several post-Mughal states, notably Bengal Subah and the Kingdom of Mysore, which were comparable to Britain in the late 18th century, until British colonial policies caused deindustrialization.[145]

Up until the 19th century, India was the world's leading cotton textile manufacturer,[150] with Bengal and Mysore the centers of cotton production.[145] In order to compete with Indian imports, Britons invested in labour-saving textile manufacturing technologies during their Industrial Revolution. Following political pressure from the new industrial manufacturers, in 1813, Parliament abolished the two-centuries-old, protectionist East India Company monopoly on trade with Asia and introduced import tariffs on Indian textiles. Until then, the monopoly had restricted exports of British manufactured goods to India.[151] Exposing the Proto-industrial hand spinners and weavers in the territories the British East India Company administered in India to competition from machine spun threads, and woven fabrics, resulting in De-Proto-Industrialization,[152] with the decline of native manufacturing opening up new markets for British goods.[150] British colonization forced open the large Indian market to British goods while restricting Indian imports to Britain, and raw cotton was imported from India without taxes or tariffs to British factories which manufactured textiles from Indian cotton and sold them back to the Indian market.[153] India thus served as both an important supplier of raw goods such as cotton to British factories and a large captive market for British manufactured goods.[154] In addition, the capital amassed from Bengal following its conquest after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 was used to invest in British industries such as textile manufacturing and greatly increase British wealth.[146][147][148] Britain eventually surpassed India as the world's leading cotton textile manufacturer in the 19th century.[150] British colonial rule has been blamed for the subsequently dismal state of British India's economy, with investment in Indian industries limited since it was a colony.[155]

Economic decline in India has been traced to before British colonial rule and was largely a result of increased output in other parts of the world and Mughal disintegration. India's share of world output (24.9%) was largely a function of its share of the world population around 1600.[124][60] Between 1880 and 1930 total Indian cotton textile production increased from 1200 million yards to 3700 million yards.[156] The introduction of railways into India have been a source of controversy regarding their overall impact, but evidence points to a number of positive outcomes such as higher incomes, economic integration, and famine relief.[157][158][159][160] Per capita GDP decreased from $550 (in 1990 dollars) per person in 1700 under Mughal rule to $533 (in 1990 dollars) in 1820 under British rule, then increased to $618 (in 1990 dollars) in 1947 upon independence. Coal production increased in Bengal, largely to satisfy the demand of the railroads.[121] Life expectancy increased by about 10 years between 1870 and independence.[130]

Recent research on colonialism has been more favorable regarding its long-term impacts on growth and development.[161] A 2001 paper by Daren Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson found that nations with temperate climates and low levels of mortality were more popular with settlers and were subjected to greater degrees of colonial rule. Those nations benefited from Europeans creating more inclusive institutions that lead to higher rates of long term growth.[162] Subsequent research has confirmed that both how long a nation was a colony or how many Europeans settlers migrated there are positively correlated with economic development and institutional quality, although the relationships becomes stronger after 1700 and vary depending on the colonial power, with British colonies typically faring best.[163][164] Acemoglu et al. also suggest that colonial profits were too small a percentage of GNP to account for the divergence directly but could account for it indirectly due to the effects it had on institutions by reducing the power of absolutist monarchies and securing property rights.[165]

Culture

Rosenberg and Birdzell claim that the so-called Eastern culture of respect and unquestionable devotion to the ruling dynasty was as a result of a culture where the control of the dynasty led to a silent society that "did not ask questions or experiment without the approval or order from the ruling class". On the other hand, they claimed that the West of the late medieval era did not have a central authority or absolute state, which allowed for a free flow of ideas (Rosenberg, Birdzell, 1986). Moreover, there is another researcher who wrote that Christianity considered to be a critical issue to the emergence of liberal societies.[166] This eastern culture also supposedly showed a dismissal of change due to their "fear of failure" and disregard for the imitation of outside inventions and science; this was different from the "Western culture" which they claimed to be willing to experiment and imitate others to benefit their society. They claimed that this was a culture where change was encouraged, and sense of anxiety and disregard for comfort led them to be more innovative. Max Weber argued in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism that capitalism in northern Europe evolved when the Protestant work ethic (particularly Calvinist) influenced large numbers of people to engage in work in the secular world, developing their own enterprises and engaging in trade and the accumulation of wealth for investment. In his book The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism he blames Chinese culture for the non-emergence of capitalism in China. Chen (2012) similarly claims that cultural differences were the most fundamental cause for the divergence, arguing that the humanism of the Renaissance followed by the Enlightenment (including revolutionary changes in attitude towards religion) enabled a mercantile, innovative, individualistic, and capitalistic spirit. For Ming China, he claims there existed repressive measures which stifled dissenting opinions and nonconformity. He claimed that Confucianism taught that disobedience to one's superiors was supposedly tantamount to "sin". In addition Chen claimed that merchants and artificers had less prestige than they did in Western Europe.[24] Justin Yifu Lin has argued for the role of the imperial examination system in removing the incentives for Chinese intellectuals to learn mathematics or to conduct experimentation.[23]

However, many scholars who have studied Confucian teachings have criticized the claim that the philosophy promoted unquestionable loyalty to one's superiors and the state. The core of Confucian philosophy itself was already humanist and rationalist; it "[does] not share a belief in divine law and [does] not exalt faithfulness to a higher law as a manifestation of divine will."[167]

One of the central teachings of Confucianism is that one should remonstrate with authority. Many Confucians throughout history disputed their superiors in order to not only prevent the superiors and the rulers from wrongdoing, but also to maintain the independent spirits of the Confucians.[168]

Furthermore, the merchant class of China throughout all of Chinese history were usually wealthy and held considerable influence above their supposed social standing.[169] Historians like Yu Yingshi and Billy So have shown that as Chinese society became increasingly commercialized from the Song dynasty onward, Confucianism had gradually begun to accept and even support business and trade as legitimate and viable professions, as long as merchants stayed away from unethical actions. Merchants in the meantime had also benefited from and utilized Confucian ethics in their business practices. By the Song period, the scholar-officials themselves were using intermediary agents to participate in trading.[169] This is true especially in the Ming and Qing dynasties, when the social status of merchants had risen to such significance[170][171][172] that by the late Ming period, many scholar-officials were unabashed to declare publicly in their official family histories that they had family members who were merchants.[173] Consequently, while Confucianism did not actively promote profit seeking, it did not hinder China's commercial development either.

Of the developed cores of the Old World, India was distinguished by its caste system of bound labor, which hampered economic and population growth and resulted in relative underdevelopment compared to other core regions. Compared with other developed regions, India still possessed large amounts of unused resources. India's caste system gave an incentive to elites to drive their unfree laborers harder when faced with increased demand, rather than invest in new capital projects and technology. The Indian economy was characterized by vassal-lord relationships, which weakened the motive of financial profit and the development of markets; a talented artisan or merchant could not hope to gain much personal reward. Pomeranz argues that India was not a very likely site for an industrial breakthrough, despite its sophisticated commerce and technologies.[174]

Aspects of Islamic law have been proposed as an argument for the divergence for the Muslim world. Economist Timur Kuran argues that Islamic institutions which had at earlier stages promoted development later started preventing more advanced development by hampering formation of corporations, capital accumulation, mass production, and impersonal transactions.[175] Other similar arguments proposed include the gradual prohibition of independent religious judgements (Ijtihad) and a strong communalism which limited contacts with outside groups and the development of institutions dealing with more temporary interactions of various kinds, according to Kuran.[176] According to historian Donald Quataert, however, the Ottoman Middle East's manufacturing sector was highly productive and evolving in the 19th century. Quataert criticizes arguments rooted in Orientalism, such as "now-discredited stereotypes concerning the inferiority of Islam", economic institutions having stopped evolving after the Islamic Golden Age, and decline of Ijtihad in religion negatively affecting economic evolution.[177] Economic historian Paul Bairoch noted that Ottoman law promoted liberal free trade earlier than Britain and the United States, arguing that free trade had a negative economic impact on the Ottoman Empire and contributed to its deindustrialization, in contrast to the more protectionist policies of Britain and the United States in the early 19th century.[106]

Representative government

A number of economists have argued that representative government was a factor in the Great Divergence.[3][135] They argue that absolutist governments, where rulers are not broadly accountable, are prone to corruption and rent-seeking while hurting property rights and innovation.[3][178] Representative governments however were accountable to broader segments of the population and thus had to protect property rights and not rule in arbitrary ways, which caused economic prosperity.[3]

Globalization

A 2017 study in the American Economic Review found that "globalization was the major driver of the economic divergence between the rich and the poor portions of the world in the years 1850–1900."[179][180] The states that benefited from globalization were "characterised by strong constraints on executive power, a distinct feature of the institutional environment that has been demonstrated to favour private investment."[180] One of other advantages was transformation in technological power in U.S. and Europe. As an illustration, in 1839 Chinese rulers decided to ban the trade with British merchants who flooded China with opium. However, “China’s creaking imperial navy was no match for a small fleet of British gunboats, driven by steam engines and shielded with steel armour”.[90]

Chance

A number of economic historians have posited that the Industrial Revolution may have partly occurred where and when it did due to luck and chance.[181][182][183]

The Black Death

Historian James Belich has argued that the Black Death, a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Afro-Eurasia from 1346 to 1353, set the conditions that made the Great Divergence possible. He argues that the pandemic, which caused mass death in Europe, doubled the per capita endowment of everything. A labor scarcity led to expanded use of waterpower, wind power, and gunpowder, as well as fast-tracked innovations in water-powered blast furnaces, heavily gunned galleons, and musketry.[184]

Economic effects

The Old World methods of agriculture and production could only sustain certain lifestyles. Industrialization dramatically changed the European and American economy and allowed it to attain much higher levels of wealth and productivity than the other Old World cores. Although Western technology later spread to the East, differences in uses preserved the Western lead and accelerated the Great Divergence.[99]

Productivity

When analyzing comparative use-efficiency, the economic concept of total factor productivity (TFP) is applied to quantify differences between countries.[99] TFP analysis controls for differences in energy and raw material inputs across countries and is then used to calculate productivity. The difference in productivity levels, therefore, reflects efficiency of energy and raw materials use rather than the raw materials themselves.[185] TFP analysis has shown that Western countries had higher TFP levels on average in the 19th century than Eastern countries such as India or China, showing that Western productivity had surpassed the East.[99]

Per capita income

Some of the most striking evidence for the Great Divergence comes from data on per capita income.[99] The West's rise to power directly coincides with per capita income in the West surpassing that in the East. This change can be attributed largely to the mass transit technologies, such as railroads and steamboats, that the West developed in the 19th century.[99] The construction of large ships, trains, and railroads greatly increased productivity. These modes of transport made moving large quantities of coal, corn, grain, livestock and other goods across countries more efficient, greatly reducing transportation costs. These differences allowed Western productivity to exceed that of other regions.[99]

Economic historian Paul Bairoch has estimated the GDP per capita of several major countries in 1960 US dollars after the Industrial Revolution in the early 19th century, as shown below.[186]

His estimates show that the GDP per capita of Western European countries rose rapidly after industrialization.

For the 18th century, and in comparison to non-European regions, Bairoch in 1995 stated that, in the mid-18th century, "the average standard of living in Europe was a little bit lower than that of the rest of the world."[21]

Agriculture

Before and during the early 19th century, much of continental European agriculture was underdeveloped compared to Asian Cores and England. This left Europe with abundant idle natural resources. England, on the other hand, had reached the limit of its agricultural productivity well before the beginning of the 19th century. Rather than taking the costly route of improving soil fertility, the English increased labor productivity by industrializing agriculture. From 1750 to 1850, European nations experienced population booms; however, European agriculture was barely able to keep pace with the dietary needs. Imports from the Americas, and the reduced caloric intake required by industrial workers compared to farmers allowed England to cope with the food shortages.[187] By the turn of the 19th century, much European farmland had been eroded and depleted of nutrients. Fortunately, through improved farming techniques, the import of fertilizers, and reforestation, Europeans were able to recondition their soil and prevent food shortages from hampering industrialization. Meanwhile, many other formerly hegemonic areas of the world were struggling to feed themselves – notably China.[188]

Fuel and resources

The global demand for wood, a major resource required for industrial growth and development, was increasing in the first half of the 19th century. A lack of interest of silviculture in Western Europe, and a lack of forested land, caused wood shortages. By the mid-19th century, forests accounted for less than 15% of land use in most Western European countries. Fuel costs rose sharply in these countries throughout the 18th century and many households and factories were forced to ration their usage, and eventually adopt forest conservation policies. It was not until the 19th century that coal began providing much needed relief to the European energy shortage. China had not begun to use coal on a large scale until around 1900, giving Europe a huge lead on modern energy production.[189]

Through the 19th century, Europe had vast amounts of unused arable land with adequate water sources. However, this was not the case in China; most idle lands suffered from a lack of water supply, so forests had to be cultivated. Since the mid-19th century, northern China's water supplies have been declining, reducing its agricultural output. By growing cotton for textiles, rather than importing, China exacerbated its water shortage.[190] During the 19th century, supplies of wood and land decreased considerably, greatly slowing growth of Chinese per capita incomes.[191]

Trade

During the era of European imperialism, periphery countries were often set up as specialized producers of specific resources. Although these specializations brought the periphery countries temporary economic benefit, the overall effect inhibited the industrial development of periphery territories. Cheaper resources for core countries through trade deals with specialized periphery countries allowed the core countries to advance at a much greater pace, both economically and industrially, than the rest of the world.[192]

Europe's access to a larger quantity of raw materials and a larger market to sell its manufactured goods gave it a distinct advantage through the 19th century. In order to further industrialize, it was imperative for the developing core areas to acquire resources from less densely populated areas, since they lacked the lands required to supply these resources themselves. Europe was able to trade manufactured goods to their colonies, including the Americas, for raw materials. The same sort of trading could be seen throughout regions in China and Asia, but colonization brought a distinct advantage to the West. As these sources of raw materials began to proto-industrialize, they would turn to import substitution, depriving the hegemonic nations of a market for their manufactured goods. Since European nations had control over their colonies, they were able to prevent this from happening.[193] Britain was able to use import substitution to its benefit when dealing with textiles from India. Through industrialization, Britain was able to increase cotton productivity enough to make it lucrative for domestic production, and overtake India as the world's leading cotton supplier.[150] Although Britain had limited cotton imports to protect its own industries, they allowed cheap British products into colonial India from the early 19th century.[194] The colonial administration failed to promote Indian industry, preferring to export raw materials.[195]

Western Europe was also able to establish profitable trade with Eastern Europe. Countries such as Prussia, Bohemia and Poland had very little freedom in comparison to the West; forced labor left much of Eastern Europe with little time to work towards proto-industrialization and ample manpower to generate raw materials.[196]

Guilds and journeymanship

A 2017 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics argued, "medieval European institutions such as guilds, and specific features such as journeymanship, can explain the rise of Europe relative to regions that relied on the transmission of knowledge within closed kinship systems (extended families or clans)".[197] Guilds and journeymanship were superior for creating and disseminating knowledge, which contributed to the occurrence of the Industrial Revolution in Europe.[197]

See also

Books

- Before and Beyond Divergence

- Civilization: The West and the Rest

- The Civilizing Process

- The Clash of Civilizations

- The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation

- The European Miracle

- A Farewell to Alms

- How the West Won: The Neglected Story of the Triumph of Modernity

- Great Divergence and Great Convergence

- The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy

- Guns, Germs, and Steel

- The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers

- The Rise of the West

- The Wealth and Poverty of Nations

- Why the West Rules—For Now

- The WEIRDest People in the World

- The Great Escape: A Review Essay on Escape from Rome: The Failure of Empire and the Road to Prosperity

References

Citations

- Maddison 2007, p. 382, Table A.7.

- Bassino, Jean-Pascal; Broadberry, Stephen; Fukao, Kyoji; Gupta, Bishnupriya; Takashima, Masanori (2018-12-01). "Japan and the great divergence, 730–1874" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 72: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2018.11.005. hdl:10086/29758. ISSN 0014-4983. S2CID 134669975.

- Allen, Robert C. (2011). Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press Canada. ISBN 978-0-19-959665-2.

Why has the world become increasingly unequal? Both 'fundamentals' like geography, institutions, or culture and 'accidents of history' played a role.

- pseudoerasmus (2014-06-12). "The Little Divergence". pseudoerasmus. Archived from the original on 2019-09-01. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- "Business History, the Great Divergence and the Great Convergence". HBS Working Knowledge. 2017-08-01. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- Vries, Peer. "Escaping Poverty".

- Bassino, Jean-Pascal; Broadberry, Stephen; Fukao, Kyoji; Gupta, Bishnupriya; Takashima, Masanori (2018-12-01). "Japan and the great divergence, 730–1874" (PDF). Explorations in Economic History. 72: 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.eeh.2018.11.005. hdl:10086/29758. ISSN 0014-4983. S2CID 134669975.

- Pomeranz 2000, pp. 36, 219–225.

- Hobson 2004, p. 77.

- Bairoch 1995, pp. 101–108.

- Goldstone, Jack A. (2015-04-26). "The Great and Little Divergence: Where Lies the True Onset of Modern Economic Growth?". SSRN 2599287.

- Korotayev, Andrey; Zinkina, Julia; Goldstone, Jack (June 2015). "Phases of global demographic transition correlate with phases of the Great Divergence and Great Convergence". Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 95: 163–169. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2015.01.017.

- Frank 2001, p. 180.

- Jones 2003.

- Frank 2001.

- Grinin L., Korotayev A., Goldstone J. Great Divergence and Great Convergence. A Global Perspective. Heidelberg – New York – Dordrecht – London: Springer, 2015.

- Maddison 2001, pp. 51–52.

- Pomeranz 2000.

- Parthasarathi 2011, pp. 38–45.

- Robert C. Allen, Tommy Bengtsson, Martin Dribe (2005), Living Standards in the Past: New Perspectives on Well-Being in Asia and Europe, page 173-188, Oxford University Press

- Chris Jochnick, Fraser A. Preston (2006), Sovereign Debt at the Crossroads: Challenges and Proposals for Resolving the Third World Debt Crisis, pages 86–87, Oxford University Press

- Jeffrey G. Williamson, David Clingingsmith (August 2005). "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- Justin Yifu Lin, "Demystifying the Chinese Economy", 2011, Cambridge University Press, Preface xiv, http://assets.cambridge.org/97805211/91807/frontmatter/9780521191807_frontmatter.pdf

- Chen 2012.

- Broadberry, Stephen, and Bishnupriya Gupta. "The Early Modern Great Divergence: Wages, Prices and Economic Development in Europe and Asia, 1500-1800." The Economic History Review, New Series, 59, no. 1 (2006): 2-31. Pages 19-20, and 9.

- Broadberry, p. 17.

- Broadberry, p.3

- "The 6 killer apps of prosperity". Ted.com. 11 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 February 2014. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 219.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 187.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 241.

- Koyama, M., & Rubin, J. (2022). How the world became rich: The historical origins of economic growth. John Wiley & Sons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - North & Thomas 1973, pp. 11–13.

- Bolt, Jutta; van Zanden, Jan Luiten (2014-08-01). "The Maddison Project: collaborative research on historical national accounts". The Economic History Review. 67 (3): 627–651. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.12032. ISSN 1468-0289. S2CID 154189498.

- North & Thomas 1973, pp. 16–18.

- Allen 2001.

- Goldstone, Jack A. (2021). "Dating the Great Divergence". Journal of Global History. 16 (2): 266–285. doi:10.1017/S1740022820000406. ISSN 1740-0228. S2CID 235599259.

- Pomeranz 2000, pp. 31–69, 187.

- Feuerwerker 1990, p. 227.

- Elvin 1973, pp. 7, 113–199.

- Broadberry, Stephen N.; Guan, Hanhui; Li, David D. (2017-04-01). "China, Europe and the Great Divergence: A Study in Historical National Accounting, 980–1850". SSRN 2957511.

- Elvin 1973, pp. 204–205.

- "China has been poorer than Europe longer than the party thinks". The Economist. 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- Elvin 1973, pp. 91–92, 203–204.

- Myers & Wang 2002, pp. 587, 590.

- Myers & Wang 2002, p. 569.

- Myers & Wang 2002, p. 579.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Gupta, Bishnupriya (2006-02-01). "The early modern great divergence: wages, prices and economic development in Europe and Asia, 1500–18001" (PDF). The Economic History Review (Submitted manuscript). 59 (1): 2–31. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2005.00331.x. ISSN 1468-0289. S2CID 3210777.

- Court, Victor (2020). "A reassessment of the Great Divergence debate: towards a reconciliation of apparently distinct determinants". European Review of Economic History. 24 (4): 633–674. doi:10.1093/ereh/hez015.

- Pomeranz, Kenneth; Parthasarathi, Prasannan. "THE GREAT DIVERGENCE DEBATE" (PDF). p. 25.

- Data table in Maddison A (2007), Contours of the World Economy I–2030 AD, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922720-4

- Zwart, Pim de; Lucassen, Jan (2020). "Poverty or prosperity in northern India? New evidence on real wages, 1590s–1870s†". The Economic History Review. 73 (3): 644–667. doi:10.1111/ehr.12996. ISSN 1468-0289.

- Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Nanda, J.N. (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- Parthasarathi 2011, pp. 180–182.

- Parthasarathi 2011, pp. 59, 128, 138.

- Ray, Indrajit (2011). Bengal Industries and the British Industrial Revolution (1757–1857). Routledge. pp. 57, 90, 174. ISBN 978-1-136-82552-1.

- Schmidt, Karl J. (2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 9781317476818.

- Prakash, Om (2006). "Empire, Mughal". History of World Trade Since 1450. Gale. pp. 237–240. Retrieved 3 August 2017.

- Williamson, Jeffrey G.; Clingingsmith, David (August 2005). "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Harvard University. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- Bagchi, Amiya (1976). Deindustrialization in Gangetic Bihar 1809–1901. New Delhi: People's Publishing House.

- Koyama, Mark (2017-06-15). "Jared Rubin: Rulers, religion, and riches: Why the West got rich and the Middle East did not?". Public Choice. 172 (3–4): 549–552. doi:10.1007/s11127-017-0464-6. ISSN 0048-5829. S2CID 157361622.

- Islahi, Abdul Azim (January 2012). "Book review. The long divergence: how Islamic law held back the Middle East by Timur Kuran" (PDF). Journal of King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics. Jeddah. 25 (2): 253–261. SSRN 3097613.

- Batou 1991, pp. 181–196.

- Quataert, Donald (2002). Ottoman Manufacturing in the Age of the Industrial Revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89301-5.

- Lockman, Zachary (Fall 1980). "Notes on Egyptian Workers' History". International Labor and Working-Class History. 18 (18): 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0147547900006670. JSTOR 27671322. S2CID 143330034.

- Batou 1991, p. 181.

- Batou 1991, pp. 193–196.

- Hassan, Ahmad Y (1976). Taqi al-Din and Arabic Mechanical Engineering. Institute for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo. pp. 34–35.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 251.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 214.

- Broadberry, Stephen; Bassino, Jean-Pascal; Fukao, Kyoji; Gupta, Bishnupriya; Takashima, Masanori (2017). "Japan and the Great Divergence, 730–1874". Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History. University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 2017-04-26. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- Francks, Penelope (2016). "Japan in the Great Divergence Debate: The Quantitative Story". Japan and the Great Divergence. Vol. 157. Palgrave Macmillan, London. pp. 31–38. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-57673-6_4. ISBN 978-1-137-57672-9.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 37.

- Dincecco, Mark (October 2017). State Capacity and Economic Development by Mark Dincecco. doi:10.1017/9781108539913. ISBN 978-1-108-53991-3.

- Wonders of the African World - Episodes - The Swahili Coast - Wonders".

- Pouwels, Randall L. (2005). The African and Middle Eastern World, 600–1500. Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780195176735.

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 319. ISBN 9781107507180.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 65.

- Pomeranz 2000, pp. 62–66.

- Clark, Gregory; Jacks, David. "Coal and the Industrial Revolution, 1700-1869" (PDF).

- McCloskey, Deidre (2010). Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can't Explain the Modern World. pp. 170–178.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 190.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 264.

- Pomeranz 2000, p. 266.

- Watson, Peter (2005-08-30). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. HarperCollins. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-06-621064-3.

- Bai, Ying; Kung, James Kai-sing (August 2011). "Climate Shocks and Sino-nomadic Conflict". Review of Economics and Statistics. 93 (3): 970–981. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00106. ISSN 0034-6535. S2CID 57572569.

- Ko, Chiu Yu; Koyama, Mark; Sng, Tuan-Hwee (February 2018). "Unified China and Divided Europe". International Economic Review. 59 (1): 285–327. doi:10.1111/iere.12270. S2CID 36401021.

- Lin 1995.