Eustachian tube

In anatomy, the Eustachian tube (/juːˈsteɪʃən/), also called the auditory tube or pharyngotympanic tube,[1] is a tube that links the nasopharynx to the middle ear, of which it is also a part. In adult humans, the Eustachian tube is approximately 35 mm (1.4 in) long and 3 mm (0.12 in) in diameter.[2] It is named after the sixteenth-century Italian anatomist Bartolomeo Eustachi.[3]

| Eustachian tube | |

|---|---|

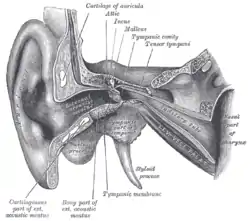

External and middle ear. Eustachian tube labelled as auditory tube. | |

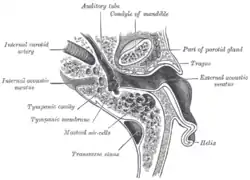

Middle ear, with auditory tube at bottom right | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /juːˈsteɪʃən/ |

| Precursor | first pharyngeal pouch |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Tuba auditiva, tuba auditivea, tuba auditoria |

| MeSH | D005064 |

| TA98 | A15.3.02.073 |

| TA2 | 6926 |

| FMA | 9705 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In humans and other tetrapods, both the middle ear and the ear canal are normally filled with air. Unlike the air of the ear canal, however, the air of the middle ear is not in direct contact with the atmosphere outside the body; thus, a pressure difference can develop between the atmospheric pressure of the ear canal and the middle ear. Normally, the Eustachian tube is collapsed, but it gapes open with swallowing and with positive pressure, allowing the middle ear's pressure to adjust to the atmospheric pressure. When taking off in an aircraft, the ambient air pressure goes from higher (on the ground) to lower (in the sky). The air in the middle ear expands as the plane gains altitude, and pushes its way into the back of the nose and mouth; on the way down, the volume of air in the middle ear shrinks, and a slight vacuum is produced. Active opening of the Eustachian tube (through actions like swallowing or the Valsalva maneuver) is required to equalize the pressure between the middle ear and the ambient atmosphere as the plane descends. A diver also experiences this change in pressure, but with greater rates of pressure change; active opening of the Eustachian tube is required more frequently as the diver goes deeper, into higher pressure.

Structure

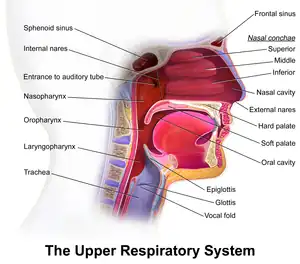

The Eustachian tube extends from the anterior wall of the middle ear to the lateral wall of the nasopharynx, approximately at the level of the inferior nasal concha. It consists of a bony part and a cartilaginous part.

Bony part

The bony part (1⁄3) nearest to the middle ear is made of bone and is about 12 mm in length. It begins in the anterior wall of the tympanic cavity, below the septum canalis musculotubarius, and, gradually narrowing, ends at the angle of junction of the squamous and the petrous parts of the temporal bone, its extremity presenting a jagged margin which serves for the attachment of the cartilaginous part.[5] The vestibule of the Eustachian tube is known as the protympanum,[6] The protympanum is also known as the anterior part of the bony part of the tube.[7]

Cartilaginous part

The cartilaginous part of the Eustachian tube is about 24 mm in length and is formed of a triangular plate of elastic fibrocartilage, the apex of which is attached to the margin of the medial end of the bony part of the tube, while its base lies directly under the mucous membrane of the nasal part of the pharynx, where it forms an elevation, the torus tubarius or cushion, behind the pharyngeal opening of the auditory tube.

The upper edge of the cartilage is curled upon itself, being bent laterally so as to present on transverse section the appearance of a hook; a groove or furrow is thus produced, which is open below and laterally, and this part of the canal is completed by fibrous membrane. The cartilage lies in a groove between the petrous part of the temporal bone and the great wing of the sphenoid; this groove ends opposite the middle of the medial pterygoid plate. The cartilaginous and bony portions of the tube are not in the same plane, the former inclining downward a little more than the latter. The diameter of the tube is not uniform throughout, being greatest at the pharyngeal opening, least at the junction of the bony and cartilaginous portions, and again increased toward the tympanic cavity; the narrowest part of the tube is termed the isthmus.

The position and relations of the pharyngeal opening are described with the nasal part of the pharynx. The mucous membrane of the tube is continuous in front with that of the nasal part of the pharynx, and behind with that of the tympanic cavity; it is covered with ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelia and is thin in the osseous portion, while in the cartilaginous portion it contains many mucous glands and near the pharyngeal orifice a considerable amount of adenoid tissue, which has been named by Gerlach the tube tonsil.

Muscles

There are four muscles associated with the function of the Eustachian tube:

- Levator veli palatini (innervated by the vagus nerve)

- Salpingopharyngeus (innervated by the vagus nerve)

- Tensor tympani (innervated by the mandibular nerve of CN V)[8]

- Tensor veli palatini (innervated by the mandibular nerve of CN V)

The tube is opened during swallowing by contraction of the tensor veli palatini and levator veli palatini, muscles of the soft palate.[1]

New anatomical perspectives

Since 2015, two developments have enhanced our understanding of the anatomy of the eustachian tube: Valsalva computerized tomography and endoscopic ear surgery.[9]

- Given the greater access to the ear anatomy using endoscopic methods, it has been suggested that the bony part of the eustachian tube is really the anterior extension of the middle ear cavity, or the "Protympanum". The term "Eustachian Tube" should be limited to the fibrocartilaginous structure connecting the protympanum to the nasopharynx.[4]

- The Eustachian tube is a saclike irregular structure rather than a tubular structure.

- The ear side of the eustchian tube is by far the narrowest segment, called isthmus, and is probably the site of possible obstructive pathology causing chronic ear disease.[10]

Development

The Eustachian tube is derived from the dorsal part of the first pharyngeal pouch and second endodermal pouch, which during embryogenesis forms the tubotympanic recess. The distal part of the tubotympanic sulcus gives rise to the tympanic cavity, while the proximal tubular structure becomes the Eustachian tube. It helps transformation of sound waves.

Frontal section through left ear; upper half of section

Frontal section through left ear; upper half of section View of the inner wall of the tympanum (enlarged)

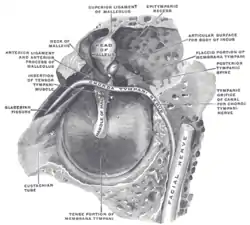

View of the inner wall of the tympanum (enlarged) The right membrana tympani with the hammer and the chorda tympani, viewed from within, from behind, and from above

The right membrana tympani with the hammer and the chorda tympani, viewed from within, from behind, and from above

Function

Pressure equalization

Under normal circumstances, the human Eustachian tube is closed, but it can open to let a small amount of air through to prevent damage by equalizing pressure between the middle ear and the atmosphere. Pressure differences cause temporary conductive hearing loss by decreased motion of the tympanic membrane and ossicles of the ear.[11] Various methods of ear clearing such as yawning, swallowing, or chewing gum may be used to intentionally open the tube and equalize pressures. When this happens, humans hear a small popping sound, an event familiar to aircraft passengers, scuba divers, or drivers in mountainous regions. Devices assisting in pressure equalization include an ad hoc balloon applied to the nose, creating inflation by positive air pressure.[12] Some people learn to voluntarily 'click' their ears, together or separately, performing a pressure equalizing routine by opening their Eustachian tubes when pressure changes are experienced, as in ascending/descending in aircraft, mountain driving, elevator lift/drops, etc. Some are even able to deliberately keep their Eustachian tubes open for a brief period, and even increase or decrease air pressure in the middle ear. The 'clicking' can actually be heard by putting one's ear to another's while performing the clicking sound. This voluntary control may be first discovered when yawning or swallowing, or by other means (above). Those who develop this ability may discover that it can be done deliberately without force even when there are no pressure issues involved.

Mucus drainage

The Eustachian tube also drains mucus from the middle ear. Upper respiratory tract infections or allergies can cause the Eustachian tube, or the membranes surrounding its opening to become swollen, trapping fluid, which serves as a growth medium for bacteria, causing ear infections. This swelling can be reduced through the use of decongestants such as pseudoephedrine, oxymetazoline, and phenylephrine.[13] Ear infections are more common in children because the tube is horizontal and shorter, making bacterial entry easier, and it also has a smaller diameter, making the movement of fluid more difficult. In addition, children's developing immune systems and poor hygiene habits make them more prone to upper respiratory infections.

Clinical significance

Otitis media, or inflammation of the middle ear, commonly affects the Eustachian tube. Children under 7 are more susceptible to this condition, one theory being that this is because the Eustachian tube is shorter and at more of a horizontal angle than in the adult ear. Others argue that susceptibility in this age group is related to immunological factors and not Eustachian tube anatomy.

Barotitis, a form of barotrauma, may occur when there is a substantial difference in air or water pressure between the outer and the middle ear – for example, during a rapid ascent while scuba diving, or during sudden decompression of an aircraft at high altitude.

Some people are born with a dysfunctional Eustachian tube[14] that is much slimmer than usual. The cause may be genetic, but it has also been posited as a condition in which the patient did not fully recover from the effects of pressure on the middle ear during birth (retained birth compression).[15] It is suggested that Eustachian tube dysfunction can result in a large amount of mucus accumulating in the middle ear, often impairing hearing to a degree. This condition is known as otitis media with effusion.

A patulous Eustachian tube is a rare condition in which the Eustachian tube remains intermittently open, causing an echoing sound of the person's own heartbeat, breathing, and speech. This may be temporarily relieved by holding the head upside down.

Smoking can also cause damage to the cilia that protect the Eustachian tube from mucus, which can result in the clogging of the tube and a buildup of bacteria in the ear, leading to a middle ear infection.[16]

Recurring and chronic cases of sinus infection can result in Eustachian tube dysfunction caused by excessive mucus production which, in turn, causes obstruction to the openings of the Eustachian tubes.

Ventilation tubes

In severe cases of childhood middle ear infections and Eustachian tube blockage, ventilation can be provided by a surgical puncturing of the eardrum to permit air equalization, known as myringotomy. The eardrum would normally naturally heal and close the hole, so a tiny plastic rimmed grommet is inserted into the hole to hold it open. This is known as a tympanostomy tube. As a child grows, the tube is eventually naturally expelled by the body. Longer-lasting vent grommets with larger flanges have been researched, but these can lead to permanent perforation of the eardrum.

Dilation of the Eustachian tube

More recently, dilation of the eustachian tube using balloon catheter has gained attention as a method of treating eustachian tube obstruction. There are two methods of performing this procedure depending on the route of the catheter introduction and the area of the Eustachian tube to be dilated. Dennis Poe popularized the transnasal introduction and the dilation of the nose side of the eustachian tube.[17] Muaaz Tarabichi pioneered the transtympanic (ear) introduction of the balloon catheter and the dilatation of the proximal part (the ear side) of the cartilaginous eustachian tube.[18][19][20]

Other animals

In the equids (horses) and some rodent-like species such as the desert hyrax, an evagination of the Eustachian tube is known as the guttural pouch and is divided into medial and lateral compartments by the stylohyoid bone of the hyoid apparatus. This is of great importance in equine medicine as the pouches are prone to infections, and, due to their intimate relationship to the cranial nerves (VII, IX, X, XI) and the internal and external carotid artery, various syndromes may arise relating to which is damaged. Epistaxis (nosebleed) is a very common presentation to veterinary surgeons and this may often be fatal unless a balloon catheter can be placed in time to suppress bleeding.

References

- Keith L. Moore; Arthur F. Dalley; A. M. R. Agur (13 February 2013). Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 970. ISBN 978-1-4511-1945-9.

- "Eustachian Tube Dysfunction or Blockage Symptoms & How to Clear". medicinenet.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- Eustachian tube at Who Named It?

- Tarabichi, Muaaz; Poe, Dennis S.; Nogueira, João Flávio; Alicandri-Ciufelli, Matteo; Badr-El-Dine, Mohamed; Cohen, Michael S.; Dean, Marc; Isaacson, Brandon; Jufas, Nicholas; Lee, Daniel J.; Leuwer, Rudolf (October 2016). "The Eustachian Tube Redefined". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 49 (5): xvii–xx. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2016.07.013. PMID 27565395.

- "Ear – Dissector Answers". Archived 2006-08-24 at the Wayback Machine at University of Michigan Medical School

- Savary, P. (1985). "The protympanum". Surgery and Pathology of the Middle Ear. pp. 65–67. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-5002-3_14. ISBN 978-94-010-8715-5.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Deng, Francis. "Protympanum | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia.

- Keidar, E.; Kwartowitz, G. (January 2020). "Tensor Tympani Syndrome". PMID 30085597.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tarabichi, Muaaz; Najmi, Murtaza (March 2015). "Visualization of the eustachian tube lumen with Valsalva computed tomography: Valsalva Computed Tomography". The Laryngoscope. 125 (3): 724–729. doi:10.1002/lary.24979. PMID 25376511. S2CID 29964314.

- Tarabichi, Muaaz; Najmi, Murtaza (November 2015). "Site of eustachian tube obstruction in chronic ear disease: Site of Eustachian Tube Obstruction". The Laryngoscope. 125 (11): 2572–2575. doi:10.1002/lary.25330. PMID 25958818. S2CID 7223491.

- Page 152 in:Rex S. Haberman (2004). Middle Ear and Mastoid Surgery. New York: Thieme Medical Pub. ISBN 1-58890-173-4.

- Leunig, A.; Mees, K. (2008). "Mittelohrbelüftung mit dem Otovent®-Latexmembran- System". Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie. 74 (6): 352–354. doi:10.1055/s-2007-997756. PMID 7662078.

- "Middle Ear, Eustachian Tube, Inflammation/Infection Treatment & Management". Medscape. Archived from the original on 2014-08-10. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- Eustachian Tube Function and Dysfunction Archived 2016-08-10 at the Wayback Machine at Baylor College of Medicine

- "FAQs – Cranial Osteopathy". The Children's Clinic. Archived from the original on 2010-05-29. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- Dubin MG, Pollock HW, Ebert CS, Berg E, Buenting JE, Prazma JP (2002). "Eustachian tube dysfunction after tobacco smoke exposure". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 126 (1): 14–19. doi:10.1067/mhn.2002.121320. PMID 11821759. S2CID 27862332.

- Poe, Dennis; Anand, Vijay; Dean, Marc; Roberts, William H.; Stolovitzky, Jose Pablo; Hoffmann, Karen; Nachlas, Nathan E.; Light, Joshua P.; Widick, Mark H.; Sugrue, John P.; Elliott, C. Layton (May 2018). "Balloon dilation of the eustachian tube for dilatory dysfunction: A randomized controlled trial: Balloon Dilation of the Eustachian Tube". The Laryngoscope. 128 (5): 1200–1206. doi:10.1002/lary.26827. PMID 28940574. S2CID 4968887.

- Tarabichi, Muaaz; Najmi, Murtaza (2015-07-03). "Transtympanic dilatation of the eustachian tube during chronic ear surgery". Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 135 (7): 640–644. doi:10.3109/00016489.2015.1009640. ISSN 0001-6489. PMID 25762371. S2CID 39239009.

- Tarabichi, Muaaz; Kapadia, Mustafa (October 2016). "The Role of Transtympanic Dilatation of the Eustachian Tube During Chronic Ear Surgery". Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 49 (5): 1149–1162. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2016.05.013. PMID 27565385.

- Kapadia, Mustafa; Tarabichi, Muaaz (October 2018). "Feasibility and Safety of Transtympanic Balloon Dilatation of Eustachian Tube". Otology & Neurotology. 39 (9): e825–e830. doi:10.1097/MAO.0000000000001950. ISSN 1531-7129. PMID 30124616. S2CID 52041093.