Exeter Madonna

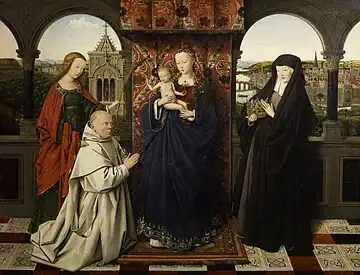

Exeter Madonna or Virgin and Child with Saint Barbara and Jan Vos are names given to a small oil-on-wood panel painting completed c. 1450[1] by the Early Netherlandish painter Petrus Christus.[2] It shows Saint Barbara presenting a Carthusian monk identified as Jan Vos, to the Virgin Mary who holds the Christ Child in her arms. Its diminutive size suggests it was meant as a personal devotional piece.

The painting is set in a loggia reminiscent of the interior of Madonna of Chancellor Rolin by Jan van Eyck – complete with a row of floor tiles separating the earthly from the heavenly realms. The panel may have been a companion piece to van Eyck's late work Madonna of Jan Vos (c. 1441).

The attribution to Christus is today undisputed, but art historians are unsure regarding the date and circumstances of the commission. In the 17th century it was thought to be by van Eyck and sold as such by the Marquis of Exeter. It was acquired by the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in 1888 and is now in Berlin's Gemäldegalerie.[2]

Commission

The Carthusian monk in the painting was identified as Jan Vos in 1938 by the art historian H. J. J. Scholtens. Vos became prior of the Charterhouse of Val-de-Grace in 1441, around when he probably commissioned Jan van Eyck's Madonna of Jan Vos . Van Eyck died in 1441 and various theories have been put forth in regards to Petrus Christus's hand in that painting. The art historian Erwin Panofsky speculated that Christus finished the van Eyck.[3] Given Christus's purchase of citizenship on July 6 1444, his ostensible arrival in Bruges at that time,[4] and Vos's movements (he was absent from Bruges for a number of years), a more probable scenario is that the Exeter Madonna was commissioned as a portable devotional piece for Vos during his travels, or on his return to Bruges in the 1450s.[5]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

It is possible that Vos gave the Madonna of Jan Vos to Christus work from. Christus seems also to have used the now lost Madonna of Nicolas van Maelbeke as a source.[7] Christus's rendition is a reinterpretion, rather than a direct copy of van Eyck's painting. Although Saint Barbara and Vos are in the same position in both paintings,[8] the most obvious difference is the exclusion of Saint Elizabeth.[2]

Description

Saint Barbara presents Jan Vos to the Virgin Mary, who holds the Christ Child in her arms.[9] She wears a red robe over a blue dress. The simple dress is only adorned with a single band of ermine fur at the hem. The attire and stance are similar in their simplicity to the Madonna of the Dry Tree by Petrus Christus.[10][11] The depiction of the child is somewhat reminiscent of van Eyck's Dresden Triptych.[12]

_(Figures).jpg.webp)

The figures are grouped in a high portico or loggia that opens to a city-view and background landscape.[9] The tradition of a donor kneeling before the Virgin is common in Early Netherlandish art, with van Eyck's Madonna of Chancellor Rolin perhaps the most notable example, which Christus would have seen. Christus borrows that painting's line of floor tiles, which are intended to separates the earthly realm from the heavenly. The art historian Maryan Ainsworth writes that Christus pushed the figures into a corner, making it more intimate and utilizing asymmetrical angles characteristic of his work.[13] The art historian Joel Morgan Upton describes the arrangement as "strictly parallel" with a foreshortened foreground, in a "diagonal, asymmetrical placement...activated by a striking oblique placement of figures."[9] The distinction between the figures and the space around them is characteristic of Christus's work, as is its one-point perspective. The viewer gazes on the Virgin from the same perspective as the kneeling monk, is drawn into the mood of the Sacra conversazione, which is emphasized by the richness of the world beyond the window.[14]

The cityscape in the near background has been identified as Bruges in the 1450s, and is depicted with an unusually high degree of detail.[9] Within the loggia, Saint Barbara's attribute of the tower resembles the Belfry of Bruges. To the exterior's far left in the square called the Huidenvettersplein people can be seen scurrying about, while and a tiny figure is visible seated a white horse. Through the center window the city's canals and small lake can be seen beneath a towered bridge.[14]

References

Citations

- Sterling (1971), p. 19

- Ainsworth (1994), p. 102

- Upton (1990), p. 14

- Upton (1990), p. 7

- Upton (1990), p. 15-17

- The Virgin and Child with Donor. Frick Collection, New York. Retrieved February 17, 2023

- The Virgin and Child with St. Barbara and Jan Vos (Exeter Virgin). Frick Collection, New York. Retrieved February 17, 2023

- Lane (1970), p. 390

- Upton (1990), p. 15

- Ainsworth (1994), p. 164

- Upton (1990), p. 60

- Ainsworth (1994), p. 105

- Ainsworth (1994), p. 104

- Upton (1990), p. 18

Sources

- Ainsworth, Maryan. Petrus Christus: Renaissance Master of Bruges. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8109-6482-2

- Lane, Barbara. "Petrus Christus: A Reconstructed Triptych with an Italian Motif". Art Bulletin, Vol. 52, No. 4, (Dec., 1970)

- Sterling, Charles. "Observations on Petrus Christus". The Art Bulletin, Vol. 53, No. 1, (Mar., 1971)

- Upton, Joel Morgan. Petrus Christus: His Place in Fifteenth-Century Flemish Painting. Penn State Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-2710-4-2862

Further reading

- Capron, Emma; Maryan Ainsworth and Till-Holger Borchert. The Charterhouse of Bruges: Jan Van Eyck, Petrus Christus, and Jan Vos. Frick Collection, 2018. ISBN 9781911282198

- Panofsky, Erwin. Early Netherlandish Painting. London: HarperCollins, 1953. ISBN 0-06-430002-1

- Falque, Ingrid, “The Exeter Madonna by Petrus Christus: Devotional Portrait and Spiritual Ascent in Early Netherlandish Painting”, in Ons geestelijk erf, 86/3, 2015, pp. 219-249.

External links

- Exhibition entry at the Frick Collection, NYC

- Frick Exhibition