Facadism

Facadism, façadism, or façadomy[1] is the architectural and construction practice where the facade of a building is designed or constructed separately from the rest of a building, or when only the facade of a building is preserved with new buildings erected behind or around it.

There are aesthetic and historical reasons for preserving building facades. Facadism can be the response to the interiors of a building becoming unusable, such as being damaged by fire. In developing areas, however, the practice is sometimes used by property developers seeking to redevelop a site as a compromise with preservationists who wish to preserve buildings of historical or aesthetic interest. It can be regarded as a compromise between historic preservation and demolition and thus has been lauded as well as decried.

There is sometimes a blurred line between renovation, adaptive reuse, reconstruction and facadism. Sometimes buildings are renovated to such an extent that they are "skinned", preserving only the exterior shell, and used for purposes other than those for which they were originally intended. While this is equivalent to facadism, the difference is typically the retention of roof and or floor structures, maintaining a credible link to the original building. In contrast, facadism generally involves retaining only one or two street facing walls for purely aesthetic and decorative purposes.[2] Facadomy is a practice in postmodern architecture reaching its peak in the latter half of the 20th century. The setback or podium architecture technique gives an illusion of integrity to the original building by visually separating the old from the new, helping to mitigate farcical effects such as the floors and windows not lining up or a dramatic clash of styles.

Critics label the practice as architectural sham, some claiming that it sometimes results in part of the building becoming a folly.

Distribution and control measures

Despite being highly controversial and denounced by many preservationists as vandalism, facadism is used as the demand for new development is overwhelming community desires for preservation. Facadism appears often in cities where there is a strong pressure for new development.

While the controversial practice of facadism is encouraged by governments in some cities (such as Toronto and Brisbane), it is actively discouraged in others (such as Paris and Sydney).

Architectural podiums are often seen by some architects as a solution to this problem and these are allowed for as part of planning frameworks in urban heritage areas.

International policies

The practice of facadism has the potential to conflict with ICOMOS international charters. The Venice Charter, article 7, states that: "A monument is inseparable from the history to which it bears witness and from the setting in which it occurs. The moving of all or part of a monument cannot be allowed except where the safeguarding of that monument demands it or where it is justified by national or international interest of paramount importance".

By country

Australia

In Australia, the Burra Charter, which sets out the principles and procedures to be followed when conserving heritage places, does not have any policies which specifically deal with facadism. However, it requires that all aspects of the significance of a place be understood and retained as far as possible. Many local governments have heritage policies, but while some specifically warn against facadism, others do not.

Sydney

The central city of Sydney sported numerous examples of historic buildings reduced to facades as part of the development boom of the 1980s. The retention of only the two street facades of the 1890s Colonial Mutual Building on Martin Place in 1976[3] to allow an office tower behind is probably the earliest example of facadism in Australia, and set a precedent for the following decade. The most notorious was the treatment of the 1850s North British Hotel in Loftus Street in 1983, where the bland office building facade rose straight up from the retained facade, and had been given the bonus floors on the basis of the preservation.[4] In 2018, a new development on a larger site saw its complete demolition, noting that it was not officially heritage protected.[5] Many warehouses and industrial buildings in the central city area were facaded in the 1980s, some left propped up for years after the building boom bust in the early 1990s. New heritage controls introduced in NSW allow the listing of interiors, and many now are, and the City of Sydney heritage guidelines[6] assume the retention of the whole of buildings that are heritage listed, and so there have been very few examples of facadism since the mid 1990s.

Melbourne

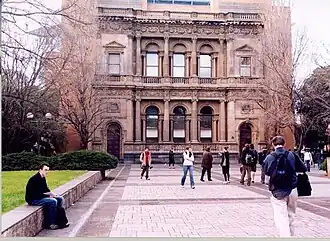

In the rapidly growing city of Melbourne, facadism has become very common. The Old Commerce building at the University of Melbourne was a very early example dating from the 1930s, however this was a case of saving an elaborate stone bank facade by relocating it to Melbourne University and reconstructed as part of a new building (which was itself demolished and replaced in 2014 with the facade left in place[7]).

With the introduction of heritage controls in the 1980s, and high profile heritage battles over a number of several large scale CBD buildings, a compromise policy avoiding facadism was generally adopted. The front portion, often about 10 metres depth of the front of a building was retained, with taller development setback behind the retained portion. One Collins Street in 1984 and the Olderfleet group development in 1986 were high profile examples.[8]

Facadism still occurred in a few examples, notably the T & G Building on Collins Street where 10 storey walls on two street fronts were propped up in 1990 allowing a completely new building behind, but the same height and floor levels as the facades.

In the early 21st century, with development pressures increasing, and policies introduced encouraging high density residential development, new non-specific controls in the central city, and a series of decisions at the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal, retention of only facades has become more and more common. By the early 2010s, industrial buildings, shop rows, and traditional corner pubs across the inner and middle city were routinely reduced to a facade (and usually some side walls to retain the appearance of a "three dimensional building"), to allow new residential construction behind and above. In 2012 the huge Myer Store on Lonsdale Street in the city was reduced to a highly visible propped facade to allow the construction of a shopping center.[9] Concern was expressed by heritage groups in 2013 that the trend has gone too far,[10] and the City of Melbourne started the process for introducing new guidelines for the central city that would curb such practices.[11]

Brisbane

In Brisbane, where heritage controls did not exist until 1992, many historic buildings were lost completely despite public opposition in the 1970s and 80s, and facadism was seen as an acceptable compromise by the Brisbane City Council. Uptown, completed in 1988 was hailed as a heritage 'success', retaining the facades of several buildings including the Hotel Carlton (1885), New York Hotel (1860) and Newspaper House. Another notorious example was the Queensland Country Life Building (1888) which was reduced to a facade in 1991, and left as a remnant for many years until a development was built behind in 2006. Guidelines for places on the State level Queensland Heritage Register however requires that interiors specifically taken into account.[12]

Canada

In Canada, all jurisdictions at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal level have adopted the Standards & Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada, which – though not explicit – does not recommend facadism as good conservation practice. In general, projects which have approached projects using facadism are considered to have lost their integrity and value. Nonetheless, facadism is very common, especially in Toronto: for example in 2017 the facades of the McLaughlin Motor Car Showroom were dismantled and re-erected as part of the Burano tower development.

Gallery

Reconstruction of an 1890s 7-storey apartment building. Malaya Nikitskaya Street, Moscow.

Reconstruction of an 1890s 7-storey apartment building. Malaya Nikitskaya Street, Moscow. The National Theatre Bucharest was destroyed in WW2, and the front was reconstructed in 2010 with a modern glass building behind.

The National Theatre Bucharest was destroyed in WW2, and the front was reconstructed in 2010 with a modern glass building behind. BNPP headquarters on boulevard des Italiens in Paris, rebuilt beside the facade of the famous former restaurant La maison dorée.

BNPP headquarters on boulevard des Italiens in Paris, rebuilt beside the facade of the famous former restaurant La maison dorée.

Reconstruction of 1918 shopoffices in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A block of shophouses across the road have received similar treatment.

Reconstruction of 1918 shopoffices in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A block of shophouses across the road have received similar treatment. The facade of 48 Leicester Square stands alone in January 2015, after demolition of the building behind it. Originally Fanum House, designed by Andrew Mather and built in three phases 1923-26, 1936–37 and 1956–59

The facade of 48 Leicester Square stands alone in January 2015, after demolition of the building behind it. Originally Fanum House, designed by Andrew Mather and built in three phases 1923-26, 1936–37 and 1956–59 In Manhattan, New York City, New York University agreed to preserve the facade of St. Anne's Church when it built a new dormitory on the site, but did not incorporate the facade into the building, leaving it freestanding in front

In Manhattan, New York City, New York University agreed to preserve the facade of St. Anne's Church when it built a new dormitory on the site, but did not incorporate the facade into the building, leaving it freestanding in front 15 Union Square West was a cast-iron building constructed for Tiffany & Company in 1870. In 2007, a steel-and-glass facade was added in front of the cast-iron facade when it was converted into condominium apartments

15 Union Square West was a cast-iron building constructed for Tiffany & Company in 1870. In 2007, a steel-and-glass facade was added in front of the cast-iron facade when it was converted into condominium apartments The First Church in Boston was rebuilt behind its 19th-century shell after a fire in 1968.

The First Church in Boston was rebuilt behind its 19th-century shell after a fire in 1968. The 46-story Hearst Tower in Manhattan rises out of a cast stone facade built as the lower floors of a never-completed 1920s skyscraper.

The 46-story Hearst Tower in Manhattan rises out of a cast stone facade built as the lower floors of a never-completed 1920s skyscraper. Scotiabank Arenain Toronto uses the two facades from a postal delivery building.

Scotiabank Arenain Toronto uses the two facades from a postal delivery building. Bank of Canada main building in Ottawa, originally built in 1937.

Bank of Canada main building in Ottawa, originally built in 1937. The atrium above the rapid-transit train platforms for Five Points (MARTA station), Atlanta, Georgia, features the original facade of the Eiseman Building, which was demolished to make way for the station in 1975.

The atrium above the rapid-transit train platforms for Five Points (MARTA station), Atlanta, Georgia, features the original facade of the Eiseman Building, which was demolished to make way for the station in 1975. Soldier Field in Chicago was completely rebuilt in 2002 and 2003, with a new seating bowl being constructed inside the historic original stadium's iconic exterior (most notably retaining the venue's distinctive colonnade).

Soldier Field in Chicago was completely rebuilt in 2002 and 2003, with a new seating bowl being constructed inside the historic original stadium's iconic exterior (most notably retaining the venue's distinctive colonnade). Facade of the former bullfighting ring Plaza de toros de las Arenas, Barcelona, Spain. Built in 1900, by 1977 it had fallen into total disuse. It was reopened in 2011 as a shopping centre named Arenas de Barcelona, on a project by Richard Rogers.

Facade of the former bullfighting ring Plaza de toros de las Arenas, Barcelona, Spain. Built in 1900, by 1977 it had fallen into total disuse. It was reopened in 2011 as a shopping centre named Arenas de Barcelona, on a project by Richard Rogers.

Facade of the former Cock & Hoop public house, Spitalfields, London, preserved as part of Lilian Knowles House (student accommodation for the London School of Economics), constructed 2005. The facade stands clear of the new building, attached by pins; the floor levels and fenestration of the two buildings are unrelated.

Facade of the former Cock & Hoop public house, Spitalfields, London, preserved as part of Lilian Knowles House (student accommodation for the London School of Economics), constructed 2005. The facade stands clear of the new building, attached by pins; the floor levels and fenestration of the two buildings are unrelated.

See also

References

Notes

- Paul Spencer Byard (1 January 1998). The Architecture of Additions: Design and Regulation. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-393-73021-0.

- Jonathan Richards (12 November 2012). Facadism. Routledge. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-1-134-88952-5.

- "Former "Colonial Mutual Life Building" Façade | NSW Environment, Energy and Science". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- "Facades and Facadism". Architecture & Design. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- "Heritage Impact Statement AMP Circular Quay Precinct" (PDF). Department of Planning LEPs Online System.

- "City of Sydney Heritage Development Control Plan 2006" (PDF). City of Sydney. 22 December 2006.

- "Melbourne School of Design". The Design Files | Australia's most popular design blog. 2015-01-07. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- Lesh, James P. (2019). "From modern to postmodern skyscraper urbanism and the rise of historic preservation in Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth, 1969–1988". Journal of Urban History. 45 (1): 126–149. doi:10.1177/0096144217737063. S2CID 149006250.

- AS 1979 (2012-03-10), Myer Lonsdale Street Demolition, retrieved 2019-08-15

- Dobbin-Thomas, Marika (2013-05-12). "History pared back to tower facades". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- Green, Shane (2015-04-26). "Melbourne looks to new rules to protect city's historic buildings". The Age. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- "Developing heritage places" (PDF). Department of Environment and Heritage Protection.

Bibliography

- The Gentle Author (2019). The Creeping Plague of Ghastly Façadism. London: Spitalfields Life Books. ISBN 9780995740167.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Goldberger, Paul (July 15, 1985). "'Facadism' on the rise: preservation or illusion?". New York Times. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- Heffern, Sarah (April 26, 2001). "When history is only skin deep". Preservation Online. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- King, John (February 22, 2005). "Insulting historic preservation". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- King, John (September 20, 2006). "Classics preserved – or are they?". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2006-09-21.

- Larkham, Peter J. (1992). "Façadism and a vernacular farmhouse: an example in East Yorkshire". Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society. 36: 119–128.

- Saunders, Matthew (1986). "Façadism". Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society. 30: 227–240.

External links

Media related to Facadism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Facadism at Wikimedia Commons