Fairey Barracuda

The Fairey Barracuda was a British carrier-borne torpedo and dive bomber designed by Fairey Aviation. It was the first aircraft of this type operated by the Royal Navy's Fleet Air Arm (FAA) to be fabricated entirely from metal.

| Barracuda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fairey Barracuda Mk II of 814th Naval Air Squadron over HMS Venerable (R63) | |

| Role | Torpedo bomber, dive bomber |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Fairey Aviation |

| Built by | Blackburn Aircraft Boulton Paul Westland Aircraft |

| First flight | 7 December 1940 |

| Introduction | 10 January 1943 |

| Primary users | Royal Navy Royal Canadian Navy Netherlands Naval Aviation Service French Air Force |

| Produced | 1941–1945 |

| Number built | 2,602[1] |

The Barracuda was developed as a replacement for the Fairey Albacore biplanes. Development was protracted due to the original powerplant intended for the type, the Rolls-Royce Exe, being cancelled. It was replaced by the less powerful Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. On 7 December 1940, the first Fairey prototype conducted its maiden flight. Early testing revealed it to be somewhat underpowered. However, the definitive Barracuda Mk II had a more powerful model of the Merlin engine, while later versions were powered by the larger and even more powerful Rolls-Royce Griffon engine. The type was ordered in bulk to equip the FAA. In addition to Fairey's own production line, Barracudas were also built by Blackburn Aircraft, Boulton Paul, and Westland Aircraft.

The type participated in numerous carrier operations during the conflict, being deployed in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and the Pacific Ocean against the Germans, Italians, and Japanese respectively during the latter half of the war. One of the Barracuda's most noteworthy engagements was a large-scale attack upon the German battleship Tirpitz on 3 April 1944. In addition to the FAA, the Barracuda was also used by the Royal Air Force, the Royal Canadian Navy, the Dutch Naval Aviation Service and the French Air Force. After its withdrawal from service during the 1950s, no intact examples of the Barracuda were preserved despite its once-large numbers, although the Fleet Air Arm Museum has ambitions to assemble a full reproduction.

Design and development

Background

In 1937 the British Air Ministry issued Specification S.24/37, which sought a monoplane torpedo bomber to satisfy Operational Requirement OR.35. The envisioned aircraft was a three-seater that would possess a high payload capacity and a high maximum speed.[1] Six submissions were received by the Air Ministry, from which the designs of Fairey and Supermarine (Type 322) were selected. A pair of prototypes of each design were ordered.[2] On 7 December 1940, the first Fairey prototype conducted its maiden flight.[3][1] The Supermarine Type 322 did not fly until 1943 and, as the Barracuda was already in production by then, its development did not progress further.

The Barracuda was a shoulder-wing cantilever monoplane [1] It had a retractable undercarriage and non-retracting tailwheel. The hydraulically-actuated main landing gear struts were of an "L" shape which retracted into a recess in the side of the fuselage and the wing, with the wheels within the wing. A flush arrestor hook was fitted directly ahead of the tail wheel. It was operated by a crew of three, who were seated in a tandem arrangement under a continuous-glazed canopy. The pilot had a sliding canopy while the other two crew members' canopy was hinged. The two rear-crew had alternate locations in the fuselage, the navigator's position having bay windows below the wings for downward visibility.[4] The wings were furnished with large Fairey-Youngman flaps which doubled as dive brakes. Originally fitted with a conventional tail, flight tests suggested that stability would be improved by mounting the stabiliser higher, similar to a T-tail, an arrangement that was implemented on the second prototype.[1] For carrier stowage the wings folded back horizontally at the roots; the small vertical protrusions on the upper wingtips held hooks that attached to the tailplane.

The Barracuda had originally been intended to be powered by the Rolls-Royce Exe X block, sleeve valve engine, but production of this powerplant was problematic and eventually abandoned, which in turn delayed the prototype's trials.[1][5] Instead, it was decided to adopt the lower-powered 12-cylinder V-type Rolls-Royce Merlin Mark 30 engine (1,260 hp/940 kW) to drive a three-bladed de Havilland propeller and the prototypes eventually flew with this configuration.[1][6] Experiences gained from the prototype's flight testing, as well as operations with the first production aircraft, designated Barracuda Mk I, revealed the aircraft to be underpowered which apparently resulted from the weight of extra equipment that had been added since the initial design phase. Only 23 Barracuda Mk Is were constructed, including five by Westland Aircraft. These aircraft were only used for trials and conversion training.[5]

Carrier landing the Barracuda was relatively straightforward due to a combination of the powerful flaps/airbrakes fitted to the aircraft and good visibility from the cockpit. Retracting the airbrakes at high speeds whilst simultaneously applying rudder would cause a sudden change in trim, which could throw the aircraft into an inverted dive.[7][6] Incidents of this occurrence proved fatal on at least five occasions during practice torpedo runs; once the problem was identified, appropriate pilot instructions were issued prior to the aircraft entering carrier service.[7]

Further development

The definitive version of the aircraft was the Barracuda Mk II which had the more powerful 1,640 hp (1,220 kW) Merlin 32 driving a four-bladed propeller.[3] A total of 1,688 Mk IIs were manufactured by several companies, including Fairey (at Stockport and Ringway) (675), Blackburn Aircraft (700), Boulton Paul (300), and Westland (13).[8] The Barracuda Mk II carried the metric wavelength ASV II (Air to Surface Vessel) radar, with the Yagi-Uda antennae carried above the wings.[9]

The Barracuda Mk III was a Mk II optimised for anti-submarine work; changes included the replacement of the metric wavelength ASV set by a centimetric ASV III variant, the scanner for which was housed in a blister under the rear fuselage.[5][3] 852 Barracuda Mk IIIs were eventually produced, 460 by Fairey and 392 by Boulton Paul.[3]

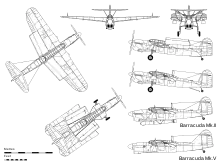

The Barracuda Mk IV never left the drawing board. The next and final variant was the Barracuda Mk V, in which the Merlin was replaced with the larger Rolls-Royce Griffon engine. The increased power and torque of the Griffon necessitated various changes, which included the enlargement of the vertical stabiliser and increased wing span with tips being clipped. The first Barracuda Mk V, which was converted from a Mk II, did not fly until 16 November 1944. Fairey had only built 37 aircraft before the war in Europe was over.

Early Merlin 30-powered Barracuda Mk 1s were deemed to be underpowered and suffered from a poor rate of climb, but once airborne the type proved relatively easy to fly. During October 1941, trials of the Barracuda Mk 1 were conducted at RAF Boscombe Down, which found that the aircraft possessed an overall weight of 12,820 lb (5,830 kg) when equipped with 1,566 lb (712 kg) torpedo. At this weight the Mk 1 had a maximum speed of 251 mph (405 km/h) at 10,900 ft (3,300 m), a climb to 15,000 ft (4,600 m) took 19.5 minutes, with a maximum climb rate of 925 ft/min (4.7 m/s) at 8,400 ft (2,560 m), and a service ceiling of 19,100 ft (5,800 m).[10]

The later Barracuda Mk II had the more powerful Merlin 32, providing a 400 hp (300 kW) increase in power. During late 1942 testing of the Mk II was performed at RAF Boscombe Down. When flown by naval test pilot Lieutenant Roy Sydney Baker-Falkner at 14,250 lb (6,477 kg) it achieved a climb to 10,000 ft (3,000 m) in 13.6 minutes,[11] with a maximum climb rate of 840 ft/min (4.3 m/s) at 5,200 ft and an effective ceiling of 15,000 ft (4,600 m).[10] During June 1943, further testing at Boscombe Down by test pilot Baker-Falkner demonstrated a maximum range while carrying either a 1,630 lb (750 kg) torpedo or a single 2,000 lb bomb (909 kg), of 840 statute miles (1,360 km), and a practical range of 650 statute miles (1,050 km), while carrying 6 x 250 lb (114 kg) bombs reduced the range to 780 miles (1,260 km) and 625 miles (1,010 km), respectively.[12]

During the earlier part of its service life the Barracuda suffered a fairly high rate of unexplained fatal crashes, often involving experienced pilots. Experienced test pilot Baker-Falkner was brought in to address the issues and boost morale amongst operational squadrons.[13][14] During 1945 the cause was traced to small leaks developing in the hydraulic system. The most common point for such a leak to happen was at the point of entry to the pilot's pressure gauge and was situated such that the resulting spray was directed straight into the pilot's face. The chosen hydraulic fluid contained ether and, as the aircraft were only rarely equipped with oxygen masks and few aircrew wore them below 10,000 ft/3,000 m anyway, the pilot quickly became unconscious during such a leak, inevitably leading to a crash.[15] At the end of May 1945 an Admiralty order was issued that required all examples of the type to be fitted with oxygen as soon as possible, and for pilots to use the system at all times.

Operational history

British service

.jpg.webp)

The first Barracudas entered operational service on 10 January 1943 with 827 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) under the command of Lieutenant Commander Roy Sydney Baker-Falkner, the former Admiralty test pilot at RAF Boscombe Down, who were deployed in the North Atlantic.[6] Eventually a total of 24 front-line FAA squadrons were equipped with Barracudas. While intended to principally function as a torpedo bomber, by the time the Barracuda arrived in quantity relatively little Axis-aligned shipping remained, so it was instead largely used as a dive-bomber.[1][16] From 1944 onwards, the Barracuda Mk II was accompanied in service by radar-equipped, but otherwise similar, Barracuda Mk IIIs; these were typically used to conduct anti-submarine operations.[17]

The Royal Air Force (RAF) also operated the Barracuda Mk II. During 1943 the first of the RAF's aircraft were assigned to No. 567 Sqn., based at RAF Detling. During 1944 similar models went to various squadrons, including 667 Sqn. at RAF Gosport, 679 Sqn. at RAF Ipswich and 691 Sqn. at RAF Roborough. Between March and July 1945 all of the RAF's Barracudas were withdrawn from service.[18][19]

During July 1943, the Barracuda first saw action with 810 Squadron aboard HMS Illustrious off the coast of Norway; shortly thereafter, the squadron was deployed to the Mediterranean Sea to support the landings at Salerno, a critical element of the Allied invasion of Italy.[20] During the following year, the Barracuda entered service in the Pacific Theatre.[21]

As the only British naval aircraft in service stressed for dive bombing following the retirement of the Blackburn Skua[16] the Barracuda participated in Operation Tungsten, an attack on the German battleship Tirpitz while it was moored in Kåfjord, Alta, Norway.[1][5] On 3 April 1944, Strike Leader Roy Sydney Baker-Falkner led two Naval Air Wings with a total of 42 aircraft dispatched from British carriers HMS Victorious and Furious scored 14 direct hits on Tirpitz using a combination of 1,600 lb (730 kg) and 500 lb (230 kg) bombs for the loss of one bomber.[22][17] This attack damaged Tirpitz, killing 122 of her crew and injuring 316, as well as disabling the ship for over two months during the critical period leading up to the Normandy invasion.[23] However, the slow speed of the Barracudas contributed to the failure of the subsequent Operation Mascot and Operation Goodwood attacks on Tirpitz during July and August of that year, but were effective as diversionary tactics whilst the Normandy landings in Operation Overlord were underway.[24][25]

On 21 April 1944 Barracudas of No 827 Squadron aboard Illustrious began operations against Japanese forces.[1][26] The type participated in air raids on Sabang in Sumatra, known as Operation Cockpit.[27] In the Pacific theatre, the Barracuda's performance was considerably reduced by the prevailing high temperatures;[N 1] reportedly, its combat radius in the Pacific was reduced by as much as 30%. This diminished performance was a factor in the decision to re-equip the torpedo bomber squadrons aboard the fleet carriers of the British Pacific Fleet with American-built Grumman Avengers.[29]

In the Pacific, a major problem hindering the Barracuda was the need to fly over Indonesian mountain ranges to strike at targets located on the eastern side of Java, which necessitated a high-altitude performance that the Barracuda's low-altitude-rated Merlin 32 engine with its single-stage supercharger could not effectively provide.[30][N 2] Additionally, the carriage of maximum underwing bomb loads resulted in additional drag, which further reduced performance.[31] However, the Light Fleet Carriers of the 11th ACS (which joined the BPF in June 1945) were all equipped with a single Barracuda and single Corsair squadron; by Victory over Japan Day, the BPF had a total of five Avenger and four Barracuda squadrons embarked on its carriers.[32]

A number of Barracudas participated in trial flights, during which several innovations were tested, including RATOG rockets for boosting takeoff performance (which ended up being regularly used when operating off escort carriers at high weights),[33] and a braking propeller, which slowed the aircraft by reversing the blade pitch.[34]

Following the end of the conflict, the Barracuda was relegated to secondary roles, for the most part being used as a trainer aircraft. The type continued to be operated by FAA squadrons up until the mid-1950s, by which time the type were withdrawn entirely in favour of the Avengers.[1]

Canadian service

On 24 January 1946, the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) took delivery of 12 radar-equipped Barracuda Mk II aircraft; this was a Canadian designation, in British service these aircraft were referred to as the Barracuda Mk. III. The first acquired aircraft were assigned to the newly-formed 825 Sqn. aboard aircraft carrier HMCS Warrior. The majority of Canadian aircraft mechanics had served during the war and had been deployed on numerous British aircraft carriers, notably HMS Puncher and Nabob which, along with some Canadian pilots, the RCN crewed and operated on behalf of the RN. During 1948, the Warrior was paid off and returned to Britain along with the Barracuda aircraft.

Variants

- Barracuda

- Two prototypes (serial numbers P1767 and P1770) based on the Fairey Type 100 design.

- Mk I

- First production version, Rolls-Royce Merlin 30 engine with 1,260 hp (940 kW), 30 built

- Mk II

- Upgraded Merlin 32 engine with 1,640 hp (1,225 kW), four-bladed propeller, ASV II radar, 1,688 built

- Mk III

- Anti-submarine warfare version of Mk II with ASV III radar in a blister under rear fuselage, 852 built

- Mk IV

- Mk II (number P9976) fitted with a Rolls-Royce Griffon engine with 1,850 hp (1,380 kW), first flight 11 November 1944, abandoned in favour of Fairey Spearfish.

- Mk V

- Griffon 37 engine with 2,020 hp (1,510 kW), payload increased to 2,000 lb (910 kg), ASH radar under the left wing, revised tailfin, 37 built

Operators

- French Air Force - Postwar

- Dutch Naval Aviation Service in exile in the United Kingdom

- 810 Naval Air Squadron

- 812 Naval Air Squadron

- 814 Naval Air Squadron

- 815 Naval Air Squadron

- 816 Naval Air Squadron

- 817 Naval Air Squadron

- 818 Naval Air Squadron

- 820 Naval Air Squadron

- 821 Naval Air Squadron

- 822 Naval Air Squadron

- 823 Naval Air Squadron

- 824 Naval Air Squadron

- 825 Naval Air Squadron

- 826 Naval Air Squadron

- 827 Naval Air Squadron

- 828 Naval Air Squadron

- 829 Naval Air Squadron

- 830 Naval Air Squadron

- 831 Naval Air Squadron

- 831 Naval Air Squadron

- 837 Naval Air Squadron

- 841 Naval Air Squadron

- 847 Naval Air Squadron

- 860 Naval Air Squadron

- 700 Naval Air Squadron

- 701 Naval Air Squadron

- 702 Naval Air Squadron

- 703 Naval Air Squadron

- 705 Naval Air Squadron

- 706 Naval Air Squadron

- 707 Naval Air Squadron

- 710 Naval Air Squadron

- 711 Naval Air Squadron

- 713 Naval Air Squadron

- 714 Naval Air Squadron

- 716 Naval Air Squadron

- 717 Naval Air Squadron

- 719 Naval Air Squadron

- 731 Naval Air Squadron

- 733 Naval Air Squadron

- 735 Naval Air Squadron

- 736 Naval Air Squadron

- 737 Naval Air Squadron

- 744 Naval Air Squadron

- 747 Naval Air Squadron

- 750 Naval Air Squadron

- 753 Naval Air Squadron

- 756 Naval Air Squadron

- 764 Naval Air Squadron

- 767 Naval Air Squadron

- 768 Naval Air Squadron

- 769 Naval Air Squadron

- 774 Naval Air Squadron

- 778 Naval Air Squadron

- 783 Naval Air Squadron

- 785 Naval Air Squadron

- 786 Naval Air Squadron

- 787 Naval Air Squadron

- 796 Naval Air Squadron

- 798 Naval Air Squadron

- 799 Naval Air Squadron

Surviving aircraft

Over 2,500 Barracudas were delivered to the FAA, more than any other type ordered by the Royal Navy at that date. However, unlike numerous other aircraft of its era, none were retained for posterity and no complete examples of the aircraft exist today.[38][39]

Since the early 1970s, the Fleet Air Arm Museum has been collecting Barracuda components from a wide variety of sources throughout the British Isles; it has the long-term aim of rebuilding an example. In 2010, help was sought from the team rebuilding Donald Campbell's record-breaking speed boat, Bluebird, as the processes and skills involved were related to those needed to recreating the aircraft from the crashed remains, so between May 2013 and February 2015 'The Barracuda Project' operated as a sister project to the Bluebird rebuild. The tail section of LS931 was reconstructed using only original material. During September 2014, the wreckage of a rear fuselage was delivered to the workshops to undergo the same processes. In February 2015, the Barracuda sections were transported back to the Fleet Air Arm Museum, where the work continues.[40][41]

During 2018 the wreckage of a Fairey Barracuda was discovered by engineers surveying the seabed for an electricity cable between England and France. According to Wessex Archaeology it is the only example of the type to have ever been found in one piece and represents the last of its kind in the UK. During 2019 the wreckage was successfully recovered and it was intended at that time to be reassembled and transported to the Fleet Air Arm Museum for preservation.[42][38]

Specifications (Barracuda Mk II)

Data from Fairey Aircraft since 1915,[43] British Naval Aircraft since 1912, The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II[5]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3

- Length: 39 ft 9 in (12.12 m)

- Wingspan: 49 ft 2 in (14.99 m)

- Height: 15 ft 2 in (4.62 m)

- Wing area: 405 sq ft (37.6 m2)

- Empty weight: 9,350 lb (4,241 kg)

- Gross weight: 13,200 lb (5,987 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 14,100 lb (6,396 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Rolls-Royce Merlin 32 V-12 liquid-cooled piston engine, 1,640 hp (1,220 kW)

- Propellers: 4-bladed constant-speed propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 240 mph (390 km/h, 210 kn)

- Cruise speed: 195 mph (314 km/h, 169 kn)

- Range: 1,150 mi (1,850 km, 1,000 nmi)

- Combat range: 686 mi (1,104 km, 596 nmi) with 1,620 lb (735 kg) torpedo

- Service ceiling: 16,000 ft (4,900 m)

- Time to altitude: 5,000 ft (1,524 m) in 6 minutes

- Wing loading: 32.6 lb/sq ft (159 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.12 hp/lb (0.20 kW/kg)

Armament

- Guns: 2 × 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine guns in rear cockpit

- Bombs: 1× 1,620 lb (735 kg) aerial torpedo or 4× 450 lb (205 kg) depth charges or 6× 250 lb (110 kg) bombs

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Curtiss SB2C Helldiver

- Douglas TBD Devastator

- Grumman TBF Avenger

- Nakajima B6N

- Supermarine Type 322

- Yokosuka D4Y

Related lists

References

Notes

- All aircraft are adversely affected by increased temperature and humidity. The effect is to lower engine output and increase the takeoff run. Additionally, windless conditions are common very near the equator, further increasing the takeoff run for carrier aircraft.[28]

- " Illustrious then exchanged her Barracudas for the Avengers of 832 and 851 before the next operation, an attack on the oil refineries at Soerabaya, Java. For this strike, the aircraft would have to fly across the breadth of Java. The mountainous spine of the island averages 10,000 ft in height, and this minimum height, coupled with the distance to be flown, about 240 miles, prohibited the use of the essentially low altitude Barracuda."[30]

Citations

- Fredriksen 2001, p. 106.

- Taylor 1974, p. 313.

- Taylor 1974, p. 314.

- Bridgman, Leonard. Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. New York: Crescent Books, 1988. ISBN 0-517-67964-7. .

- Bishop 1998, p. 401.

- Smith 2008, p. 337.

- Brown 1980, pp. 105–106.

- "Fairey Barracuda." Flight International, 10 August 1944. p. 148.

- Harrison 2002, p. 26.

- Mason 1998, pp. 294, 306.

- Pilot's Notes for Barracuda Marks II and III Merlin 32 engine. London: Air Ministry, February 1945. p.19; at a weight of 13,900 lb, the normal takeoff weight with a 1,630 lb torpedo, the time to climb to 10,000 ft was 12.57 minutes, and climb rates were calculated with the maximum continuous power of the Merlin 32 engine, rather than the 5 minute combat rating.

- Mason 1998, p. 295.

- Popham, Hugh. Sea Flight. London: Futura Publications, 1974, First edition, London: William Kimber & Co, 1954. p.163. ISBN 0-8600-7131-6

- Kilbracken 1980, p. 197.

- Kilbracken 1980, p. 203.

- Smith 2008, p. 333.

- Gunston, Bill. Classic World War II Aircraft Cutaways. London: Osprey, 1995. pp.120-1.ISBN 1-85532-526-8.

- Jefford 2001, Chapter The Squadrons.

- Halley 1988, pp. 411, 436, 451, 452, 457.

- Willis 2009, pp. 72–73.

- Harrison 2002, pp. 31–32

- Willis 2009, pp. 74–75.

- Smith 2008, pp. 337, 339.

- Roskill, S.W. The War at Sea 1939–1945. Volume III: The Offensive Part II. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1961. pp. 156, 161–162. OCLC 59005418.

- "Bombs away." Gisborne Herald, 29 December 2018.

- Smith 2008, pp. 339-340.

- Willis 2009, p. 75.

- "Effect of temperature and altitude on airplane performance." pilotfriend.com. Retrieved: 26 September 2010.

- Willis 2009, pp. 75–76.

- Brown 1972, p. 257.

- Harrison 2002, p. 29.

- Watson, Graham. "Royal Navy: Fleet Air Army, August 1945." Archived 2 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine orbat.com, v.1.0 7 April 2002. Retrieved: 17 April 2010.

- Harrison 2002, p. 16

- Harrison 2002, p. 20

- Lewis 1959, p. 112.

- Lewis 1959, p. 124.

- "Lost WW2 Aircraft lifted from sea after more than 75 years." heritagedaily.com, 5 June 2019.

- Moss, Richard. "Fleet Air Arm reveals progress on project to restore last World War II Barracuda bomber." culture24.org.uk, 25 August 2011.

- "Barracuda Project". Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Museum. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "WWII Barracuda bomber to be rebuilt from crash wreckage." BBC News, 30 October 2013.

- "'Rare' WWII bomber lifted from sea 75 years after crash." BBC News, 7 June 2019.

- Taylor 1974, p. 325.

Bibliography

- Bishop, Chris (Ed) "The Encyclopedia of Weapons of World War II." Orbis Publishing Ltd, 1998. ISBN 0-7607-1022-8.

- Brown, Eric, CBE, DCS, AFC, RN.; William Green, and Gordon Swanborough. "Fairey Barracuda". Wings of the Navy, Flying Allied Carrier Aircraft of World War Two. London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1980, pp. 99–108. .

- Brown, J. David. Fairey Barracuda Mks. I-V (Aircraft in profile 240). Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications Ltd., 1972.

- Brown, David. HMS Illustrious Aircraft Carrier 1939-1956: Operational History (Warship Profile 11). London: Profile Publications, 1971.

- Fredriksen, John C. International Warbirds: An Illustrated Guide to World Military Aircraft, 1914-2000. ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 0-7106-0002-XISBN 1-57607-364-5.

- Hadley, D. Barracuda Pilot. London: AIRlife Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-84037-225-7.

- Halley, James J. The Squadrons of the Royal Air Force & Commonwealth 1918–1988. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians) Ltd., 1988. ISBN 0-85130-164-9.

- Harrison, W.A. Fairey Barracuda, Warpaint No.35. Luton, Bedfordshire, UK: Hall Park Books Ltd., 2002.

- Jefford, C.G. RAF Squadrons, a Comprehensive Record of the Movement and Equipment of all RAF Squadrons and their Antecedents since 1912. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-84037-141-2.

- Kilbracken, Lord. Bring Back my Stringbag. London, Pan Books Ltd., 1980 (also London: Peter Davies Ltd, 1979), ISBN 0-330-26172-X.

- Lewis, Peter. Squadron Histories: R.F.C., R.N.A.S. and R.A.F. 1912–59. London: Putnam, 1959.

- Mason, Tim. The Secret Years: Flight Testing at Boscombe Down, 1939-1945. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications, 1998. ISBN 0-9519899-9-5.

- Smith, Peter C. Dive Bomber!: Aircraft, Technology, and Tactics in World War II. Stackpole Books, 2008. ISBN 0-811-74842-1

- Taylor, H.A. Fairey Aircraft Since 1915. London: Putnam, 1974. ISBN 0-370-00065-X.

- Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London: Putnam, Fifth edition, 1982. ISBN 0-370-30021-1.

- Willis, Matthew. "Database: The Fairey Barracuda." Aeroplane Monthly, May 2009, Vol. 37, No. 5, pp. 57–77.

External links

- The Barracuda Project Barracuda restoration project

- The Fairey Swordfish, Albacore, & Barracuda

- Newsreel film of the Barracuda's attack on Tirpitz Archived 11 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Newsreel about the life and death of the Tirpitz showing the Barracuda in action