Faqir of Ipi

Haji Mirzali Khan Wazir (Pashto: حاجي میرزاعلي خان وزیر), commonly known as the Faqir of Ipi (فقير ايپي), was a tribal chief and adversary to the British Raj in India from North Waziristan in today's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.[1][2]

Haji Mirzali Khan حاجي میرزاعلي خان | |

|---|---|

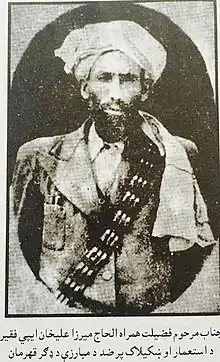

Only authentic photo of Faqir IPI | |

| Born | c. 1897 |

| Died | 16 April 1960 (aged 62–63) Gurwek, North Waziristan, Pakistan |

| Resting place | Gurwek, North Waziristan, Pakistan |

| Known for |

|

| Parent | Sheikh Arsala Khan |

After performing his Hajj pilgrimage in 1923, Mirzali Khan settled in Ipi, a village located near Mirali in North Waziristan, from where he started a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the British Empire. He was witnessed the massacre of peaceful "Khudai Khidmatgars" by the British troops at Qissa Khawani Bazar in Peahawar on 23 April 1930. In 1938, he shifted from Ipi to Gurwek, a remote village in North Waziristan on the border with Afghanistan, where he declared an independent state, Pashtunistan and continued his raids against the British, using bases in Afghanistan,[3] with the support of Nazi Germany.[4][5]

On 21 June 1947, the Faqir of Ipi, along with his allies including the Khudai Khidmatgars and members of the Provincial Assembly, declared the Bannu Resolution which demanded that the native Pashtuns be given a third choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan.[6] The British government refused to comply with this demand.[7][8]

After the creation of Pakistan in August 1947, Afghanistan financially sponsored the Pashtunistan movement under the leadership of the Faqir of Ipi.[9] He started the guerilla warfare against the new nation's government.[10] However, he couldn't succeed and his resistance diminished in early 1950s.[11]

Early life

Mirzali Khan was born around 1897 at Shankai Kirta, a village near Khajuri in the Tochi Valley of North Waziristan, present day Pakistan to Sheikh Arsala Khan Wazir.[12]

He belonged to the Pashtuns ethnicity of the Torikhel branch of the Utmanzai Wazir tribe.[13] His father died when he was twelve. He studied until fourth grade at a government school and later pursued religious studies at Bannu.

He built a mosque and a house at Spalga, further south in North Waziristan agency in 1922. He went to perform Hajj at Mecca and later moved to Ipi in mid 1920s. He became a religious figure among the locals and was called "Haji Sahab" and being the local Kanungoh of the region is famous for the introduction of both Sharia and Qanun law to Waziristan and for the introduction of the formal administration of justice and fairness in Ipi.

Restoration of King Amanullah Khan

In 1933, the Faqir of Ipi went to Afghanistan to fight against the Mohammadzai Afghan King at Khost to support the restoration of King Amanullah Khan. In 1944, the Faqir of Ipi joined his fellow Loya Paktia tribesmen again to support the restoration of Amanullah Khan in the Afghan tribal revolts of 1944–1947.[14] Until his death, the Faqir of Ipi remained involved in Afghan politics.[11]

Ram Kori case

In March 1936, a British Indian court ruled against the marriage of Islam Bibi, née Ram Kori, a Hindu-converted Muslim girl at Jandikhel, Bannu, after the girl's family filed case of abduction and forced conversion.

The ruling was based on the fact that the girl was a minor and was asked to make her decision of conversion and marriage after she reaches the age of majority, until then she was asked to live with a third party.[15] The verdict enraged the Pashtuns, and further mobilized the Faqir of Ipi for a guerrilla campaign against the British Empire.

The Dawar Maliks and mullahs left the Tochi for the Khaisor Valley to the south to rouse the Torikhel Wazirs. A month after the incident, the Faqir of Ipi called a tribal jirga (Pashtun council) in the village of Ipi near Mirali to declare war against the British Empire.

Conflict with the British Raj

Faqir's decision to declare war against the British was endorsed by the local Pashtun tribes, who mustered two large lashkars 10,000 strong to battle the British. Many Pashtun women also took part in Ipi's guerilla campaigns, not only actively participated in the campaign but also singing landai (a short folk-song sung by Pashtun women) to inspire the Pashtun fighters.

Widespread lawlessness erupted as the Pashtuns blocked roads, overran outposts and ambushed convoys. In November 1936, the British Indian government sent two columns to the Khaisor river valley to rout Ipi's guerillas, but suffered heavy casualties and were forced to retreat.[16]

Soon after the Khaisor campaign a general uprising broke out throughout Waziristan. A successful British campaign suppressed the uprising, leading to the realization of the futility of confronting the British directly especially with their advantage of air power. Ipi and his militants switched to guerrilla warfare. Squadrons of the two air forces (RAF and RIAF) launched numerous sorties against Ipi's forces, including dropping jerry can petrol bombs on crop fields and strafing herds of cattle.

In 1937, the British sent over 40,000 British-Indian troops, mostly Sikhs from the Punjab, to defeat Ipi's guerillas. This was in response to an ambush by Pashtun Waziristani tribesmen in which they had killed over 50 British Indian soldiers.

However, the operation failed and by December,the troops were sent back to their cantonments. In 1939, the British Indian government claimed that the war capacity of the Faqir of Ipi's forces was enhanced by support from Nazi Germany and Italy, alleging that the Italian diplomat Pietro Quaroni drove the Italian policy for involvement in Waziristan, although the British were unable find any concerte evidence for Quaroni's involvement.[16]

The British eventually suppressed the agitation by imposing fines and by demolishing the houses of their leaders, including that of the Faqir of Ipi. However, the pyrrhic nature of their victory and the subsequent withdrawal of the troops was credited by the Pashtuns (Wazir tribe) to be a manifestation of the Faqir of Ipi's miraculous powers.

He succeeded in inducing a semblance of tribal unity (something which was noted by the British Indian government) among various sections of Pashtuns including the Khattaks, Wazirs, Dawar, Mahsuds and Bettanis. He cemented his position as religious leader by declaring a Jihad against the British.

This move also helped rally support from Pashtun tribesman across the border. In 1946, the British again attempted to decisively defeat Ipi's movement. but this effort was unsuccessful.

Jirga in Bannu

On 21 June 1947, the Faqir of Ipi, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, and other Khudai Khidmatgars held a jirga in Bannu during which they declared the Bannu Resolution, demanding that the Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan composing all Pashtun majority territories of British India, instead of being made to join the new dominions of India or Pakistan.[6]

However, the British government refused to comply with the demand of the Bannu Resolution and only the options for Pakistan and India were given.[7][8]

Pashtunistan movement

The Faqir of Ipi rejected the creation of Pakistan after the partition of India, considering Pakistan to have only come into existence at the insistence of the British.

In 1948, the Faqir of Ipi took control of North Waziristan's Datta Khel area and declared the establishment of an independent Pashtunistan, forming ties with regional leaders including Prince Mohammed Daoud Khan.

On 29 May 1949, the Faqir of Ipi called a tribal jirga in his headquarters of Gurwek and asked Pakistan to accept Pashtunistan as an independent state. He published a Pashto-language newspaper, Ghāzī, from Gurwek to promote his ideas.[16] Afghanistan also provided financial support to the Pashtunistan movement under the leadership of the Faqir of Ipi.[9] Faqir also established a rifle factory in Gurwek with the material support provided by the government of Afghanistan.[17]

In January 1950, a Pashtun loya jirga in Razmak symbolically appointed the Faqir of Ipi as the first president of the "National Assembly for Pashtunistan".

In 1953–1954, the PAF's No. 14 Squadron led an operation from Miramshah airbase and heavily bombarded the Faqir of Ipi's compound in Gurwek.[16]

Decline

After sometime, the Faqir of Ipi relations with the government of Afghanistan deteriorated and he became aloof.[17] By this time, his movement had also started losing popular support. The Pashtun tribesmen were no longer willing to fight after the departure of British as the Faqir's reasoning of waging jihad against a foreign power was no longer considered valid.[17]

Although he himself never surrendered until his death, his movement diminished after 1954 when his Commander-in-chief Mehar Dil Khan Khattak surrendered to the Pakistani authorities.[18]

Gathering at Razmak

Later on, the Faqir of Ipi, while addressing a gathering at Razmak, said that the Government of Afghanistan had sacrificed much in the name of Islam.[19] He instructed his supporters that if the Government of Afghanistan made any future plan against Pakistan in his name, they should support it.[19]

Death

The Faqir of Ipi died at night on April 16, 1960. Long suffering from asthma, during his last days, he was too sick to walk a few steps. People from far away often used to come and see him and ask for his blessing. His funeral prayers or Namaz-I-Janaza was held at Gurwek led by Maulavi Pir Rehman. Thousands of people came for his Namaz-I-Janaza. He was buried at Gurwek.

Faqir Aipee Road

Faqir Aipee Road, a main artery connecting I.J.P. Road to the Kashmir Highway in Islamabad, is named after the Faqir of Ipi.[20]

See also

Further reading

- Dr. Shah, Syed Wiqar Ali German Activities in the North-West Frontier Province War Years 1914–1945. Quaid-e-Azam University. Available online at . Last accessed on 22/03/06

- Government of Pakistan: The Frontier Corps (NWFP) Pakistan and its headquarters. Available online at Last accessed on 22/03/06

- Siddiqui A. R. Faqir of Ipi's Cross Border Nexus. Available online . Last accessed on 22/03/06.

- Hauner, Milan (Jan., 1981) One Man against the Empire: The Faqir of Ipi and the British in Central Asia on the Eve of and during the Second World War. Available online at . Last accessed on 22/03/06.

- Shah, Idries, Destination Mecca, Chapter XXIII Contains interview with and the only photograph ever taken of Fakir of Ipi (London 1957). Possibly confirms the Fakir's dervish or Sufi status.

- Batl-i-Hurriyet: Fakir of Ipi—Iman-Parwar Jihad By Dr Fazal-ur-Rehman Kitab Saraay, First Floor, Alhamd Market, Ghazni Street, Urdu Bazar, Lahore

References

- Shaista Wahab and Barry Youngerman (2007). A Brief History of Afghanistan. Infobase publishing. ISBN 9781438108193.

- "How British empire failed to tame Fakir of Ipi". The Telegraph. Retrieved 15 November 2001.

- Stewart, Jules (2007-02-22). Savage Border: The Story of the North-West Frontier. The History Press. ISBN 9780752496078.

- Motadel, David (2014-11-30). Islam and Nazi Germany's War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674724600.

- Bose, Mihir (2017-01-20). Silver: The Spy Who Fooled the Nazis: The Most Remarkable Agent of the Second World War (in Arabic). Fonthill Media.

- "Past in Perspective". The Nation. August 25, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- Ali Shah, Sayyid Vaqar (1993). Marwat, Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan (ed.). Afghanistan and the Frontier. University of Michigan: Emjay Books International. p. 256.

- H Johnson, Thomas; Zellen, Barry (2014). Culture, Conflict, and Counterinsurgency. Stanford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780804789219.

- Malik, Hafeez (2016-07-27). Soviet-Pakistan Relations and Post-Soviet Dynamics, 1947–92. Springer. ISBN 9781349105731.

- The Faqir of Ipi of North Waziristan. The Express Tribune. November 15, 2010.

- The legendary guerilla Faqir of Ipi unremembered on his 115th anniversary. The Express Tribune. April 18, 2016.

- Alan Warren (2000). Waziristan, the Faqir of Ipi, and the Indian Army: The North West Frontier Revolt of 1936-37. Oxford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0195790160.

- Rob Johnson (2011). The Afghan Way of War: How and Why They Fight. Oxford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-19-979856-8.

- Hill, George (2013-11-15). "Chapter 3, the trip (Bibliography near end of the book)". Proceed to Peshawar: The Story of a U.S. Navy Intelligence Mission on the Afghan Border, 1943. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781612513287.

Engert letter to State Department, 15 July 1944, says that the rebel leader Abdurrahman, was next in importance to the faqir of Ipi.

- Yousef Aboul-Enein; Basil Aboul-Enein (2013). The Secret War for the Middle East. Naval Institute Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1612513096.

- "Remembering the Faqir of Ipi". Asia Times. April 16, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- Mohammad Hussain Hunarmal. "The formidable Faqir". The News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021.

- "Past in Perspective". The Nation. 2019-08-24. Retrieved 2020-04-24.

- "فقیر ایپی: جنگِ آزادی کا 'تنہا سپاہی' جس نے پاکستان کے خلاف ایک آزاد مملکت 'پختونستان' کے قیام کا اعلان کیا". BBC News (in Urdu). 7 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020.

- "Work on Faqir Aipee Road inconveniences motorists". Dawn News. 9 January 2016.

The road is named after Pakhtun leader Mirza Ali Khan of Fata, who lived from 1897 to 1960, and was known as the Faqir of Aipee.