First Battle of Panipat

The first Battle of Panipat, on 20 April 1526, was fought between the invading forces of Babur and the Lodi dynasty. It took place in North India and marked the beginning of the Mughal Empire and the end of the Delhi Sultanate. This was one of the earliest battles involving gunpowder firearms and field artillery in the Indian subcontinent which were introduced by Mughals in this battle.[6]

| First Battle of Panipat | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mughal conquests | |||||||||

The battle of Panipat and the death of Sultan Ibrāhīm | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

12,000[1]–25,000 soldiers [2][3] 15–20 field guns[1] |

20,000 regular cavalry[3] 20,000 irregular cavalry[3] 30,000 infantry armed with swords, pikes, bows and bamboo rods[3][2] 1,000 elephants [4] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown |

6,000 killed in battle[5] thousands killed while retreating[5] | ||||||||

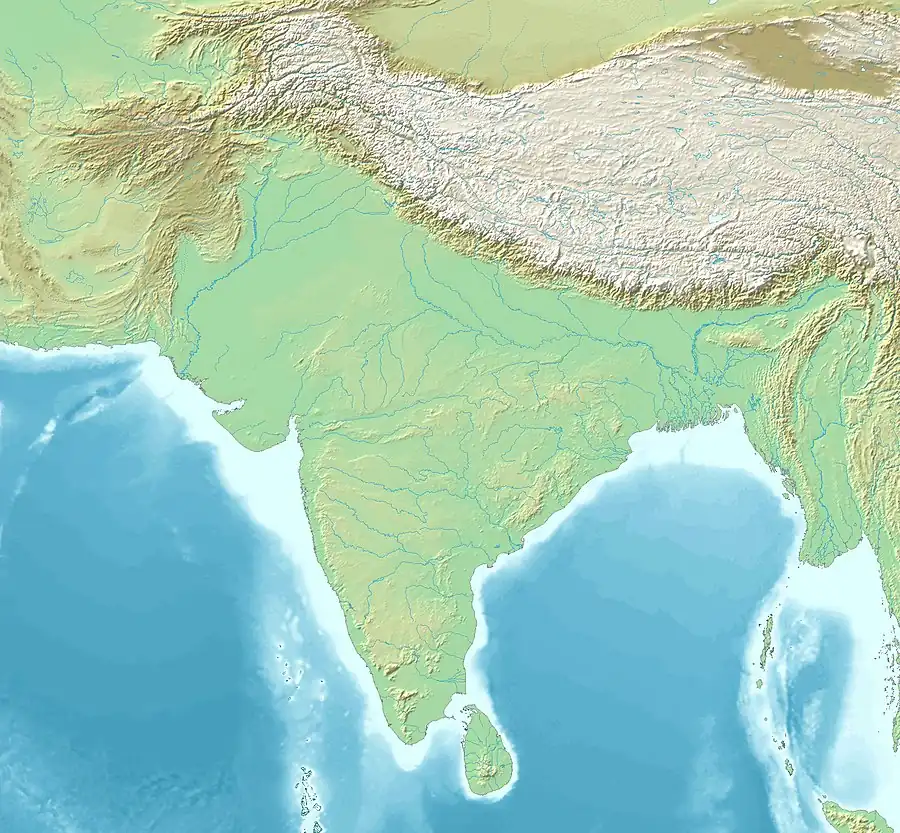

Battle of Panipat Location within South Asia  Battle of Panipat Battle of Panipat (Haryana) | |||||||||

Babur defeated the Sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodi, using a combination of tactics such as the use of firearms and cavalry charges. This battle marked the beginning of Mughal rule in India, and its aftermath had a significant impact on the political and social landscape of the country, establishing the Mughal Empire, which lasted for 231 years (1526-1757).[7]

Background

_by_Deo_Gujarati.jpg.webp)

After losing Samarkand for the second time, Babur gave attention to conquer Hindustan as he reached the banks of the Chenab in 1519.[9] Until 1524, his aim was to only expand his rule to Punjab, mainly to fulfil his ancestor Timur's legacy, since it used to be part of his empire.[10] At that time, most of North India was under the rule of Ibrahim Lodi of the Lodi dynasty, but the empire was crumbling and there were many defectors. He received invitations from Daulat Khan Lodi, Governor of Punjab and Ala-ud-Din, uncle of Ibrahim.[11] He sent an ambassador to Ibrahim, claiming himself the rightful heir to the throne of the country, however the ambassador was detained at Lahore and released months later.[9]

Babur started for Lahore, Punjab, in 1524 but found that Daulat Khan Lodi had been driven out by forces sent by Ibrahim Lodi.[12] When Babur arrived at Lahore, the Lodi army marched out and was routed.[12] In response, Babur burned Lahore for two days, then marched to Dipalpur, placing Alam Khan, another rebel uncle of Lodi's, as governor.[12] Alam Khan was quickly overthrown and fled to Kabul. In response, Babur supplied Alam Khan with troops who later joined up with Daulat Khan Lodi and together with about 30,000 troops, they besieged Ibrahim Lodi at Delhi.[13] He defeated them and drove Alam's army off; and Babur realised Lodi would not allow him to occupy the Punjab.[13]

Battle

Hearing of the size of Ibrahim's army, Babur secured his right flank against the city of Panipat, while digging a trench covered with tree branches to secure his left flank. In the centre, he placed 700 carts tied together with ropes. Between every two carts, there were breastworks for his matchlock men. Babur also ensured that there was enough space for his soldiers to rest their guns and fire. Babur referred to this method as the "Ottoman device" due to its previous use by the Ottomans during the Battle of Chaldiran.[14]

When Ibrahim's army arrived, he found the approach to Babur's army too narrow to attack. While Ibrahim redeployed his forces to allow for the narrower front, Babur quickly took advantage of the situation to flank (tulghuma) the Lodi army.[2] Many of Ibrahim's troops were unable to get into action and fled when the battle turned against them.[1] Ibrahim Lodi was killed while trying to retreat and beheaded. 20,000 Lodi soldiers were killed in battle.[2]

Advantage of cannons in the battle

Babur's guns proved decisive in battle, firstly because Ibrahim lacked any field artillery, but also because the sound of the cannon frightened Ibrahim's elephants, causing them to trample his men.[1]

Tactics

Tactics used by Babur were the tulguhma and the araba. Tulguhma meant dividing the whole army into various units, viz. the Left, the Right, and the Centre. The Left and Right divisions were further subdivided into Forward and Rear divisions. Through this, a small army could be used to surround the enemy from all sides. The Centre Forward division was then provided with carts (araba) which were placed in rows facing the enemy and tied to each other with animal hide ropes. Behind them were placed cannons protected and supported by mantlets that could be used to easily manoeuvre the cannons. These two tactics made Babur's artillery lethal. The cannons could be fired without any fear of being hit, as they were shielded by the bullock carts held in place by hiding ropes. The heavy cannons could also be easily traversed onto new targets, as they could be manoeuvred by the mantlets which were on wheels.

After Ibrahim Lodi died

Ibrahim Lodi died on the field of battle along with 20,000 of his troops. The battle of Panipat was militarily a decisive victory for the Timurids. Politically it gained Babur new lands, and initiated a new phase of his establishment of the long-lasting Mughal Empire in the heart of the Indian subcontinent, an empire that stood for over 300 years.[15]

See also

References

- Watts 2011, p. 707.

- Chandra 2009, p. 30.

- Jadunath Sarkar, Military history of India, p. 50.

- "Battles of Panipat | Summary | Britannica".

- Jadunath Sarkar, Military history of India, p. 52.

- Butalia 1998, p. 16.

- Bates, Crispin (26 March 2013). Mutiny at the Margins: New Perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857: Volume I: Anticipations and Experiences in the Locality. SAGE Publications India. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-81-321-1336-2.

- Chandra 2009, pp. 27–31.

- Mahajan 1980, p. 429.

- Eraly 2007, pp. 27–29.

- Chaurasia 2002, pp. 89–90.

- Chandra 2009, p. 27.

- Chandra 2009, p. 28.

- Chandra 2009, p. 29.

- Chandra 2009, pp. 30–31.

Sources

- Butalia, Romesh C. (1998). The Evolution of the Artillery in India: From the Battle of Plassey to the Revolt of 1857. Allied Publishing Limited.

- Chandra, Satish (2009). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals, Part II. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124110669.

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India : from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic Publisher.

- Davis, Paul K. (1999). 100 Decisive Battles: From Ancient Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 1-57607-075-1.

- Eraly, Abraham (2007). Emperors Of The Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-93-5118-093-7.

- Mahajan, V.D. (1980). History of medieval India (10th ed.). S. Chand.

- Watts, Tim J. (2011). "Battles of Panipat". In Mikaberidze, Alexander (ed.). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Government of Haryana (11 June 2010). "First Battle of Panipat (1526) | Panipat, Haryana". Government of Haryana. Retrieved 28 November 2018.