Battle of Buxar

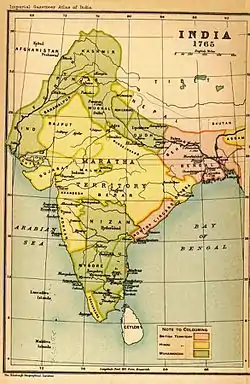

The Battle of Buxar was fought between 22 and 23 October 1764, between the forces under the command of the British East India Company, led by Hector Munro, and the combined armies of Balwant Singh, Raja of Benaras; Mir Qasim, Nawab of Bengal till 1764; the Nawab of Awadh, Shuja-ud-Daula; and the Mughal Emperor, Shah Alam II.[3] The battle was fought at Buxar, a "strong fortified town" within the territory of Bihar, located on the banks of the Gangas river about 130 kilometres (81 mi) west of Patna; it was a challenging victory for the British East India Company. The war was brought to an end by the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765.[4] The defeated Indian rulers were forced to sign this treaty, granting the East India Company diwani rights, which allowed them to collect revenue from the territories of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa on behalf of the Mughal emperor. This gave the company immense economic control, enabling them to pass financial policies to exploit the resources of the region for their own benefit.

| Battle of Buxar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Bengal War | |||||||

A portrait of Hector Munro, 8th laird of Novar | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 17,072 | 40,112 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2,000 killed 4,000 wounded[2] | |||||||

Battle

The British engaged in the fighting numbered 17,072[5] comprising 1,859 British regulars, 5,297 Indian sepoys and 9,189 Indian cavalry. The alliance army's numbers were estimated to be over 40,000. According to other sources, the combined army of the Mughals, Awadh and Mir Qasim consisting of 10,000 men[6] was defeated by a British army comprising 7,000 men. The Nawabs had gained their military power after the battle of Buxar.

The lack of basic co-ordination among the major three disparate allies was responsible for their decisive defeat.

Mirza Najaf Khan commanded the right flank of the Mughal imperial army and was the first to advance his forces against Major Hector Munro at daybreak; the British lines formed within twenty minutes and reversed the advance of the Mughals. According to the British, Durrani and Rohilla cavalry were also present and fought during the battle in various skirmishes. But by midday, the battle was over and Shuja-ud-Daula blew up large tumbrils and three massive magazines of gunpowder.

Munro divided his army into various columns and particularly pursued the Mughal Grand Vizier Shuja-ud-Daula the Nawab of Awadh who responded by blowing up his boat-bridge after crossing the river, thus abandoning the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and members of his own regiment. Mir Qasim also fled with his 3 million rupees worth of gemstones and later died in poverty in 1777. Mirza Najaf Khan reorganised formations around Shah Alam II, who retreated and then chose to negotiate with the victorious British.[7]

The historian John William Fortescue claimed that the British casualties totalled 847: 39 killed and 64 wounded from the European regiments and 250 killed, 435 wounded and 85 missing from the East India Company's sepoys.[2] He also claimed that the three Indian allies suffered 2,000 dead and that many more were wounded.[2] Another source says that there were 69 European and 664 sepoy casualties on the British side and 6,000 casualties on the Mughal side.[8] The victors captured 133 pieces of artillery and over 1 million rupees of cash. Immediately after the battle, Munro decided to assist the Marathas, who were described as a "warlike race", well known for their relentless and unwavering hatred towards the Mughal Empire and its Nawabs and Mysore.

According to one brigadier-general H. Biddulph, "the European infantry was composed of the Bengal European Battalion, two weak companies of the Bombay European Battalion, and small detachments of Marines and of H.M. 84th, 89th and 96th Regiments. The only officers killed were Lt. Francis Spilsbury of the 96th Foot and Ensign Richard Thompson of the Bengal European Battalion."[9][10]

Aftermath

The Battle of Buxar had far-reaching consequences that reshaped the political landscape of colonial India. Its aftermath witnessed significant shifts in power dynamics and set the stage for British dominance in the region. Following their victory over the combined forces of the Nawab of Bengal, the Nawab of Awadh, and the Mughal Emperor—the three main scions—the British East India Company emerged as the preeminent power in northern India. The battle effectively marked the beginning of end of the Mughal Empire's political influence, as the Company continued to consolidate its influence over vast territories.[7] However, this rise to power came with various challenges, especially from the zamindars of Bihar.[11]

Mir Qasim disappeared into impoverished obscurity. Shah Alam II surrendered himself to the British, and Shuja-ud-Daula fled west hotly pursued by the victors. The whole Ganges valley lay at the company's mercy; Shuja-ud-Daula eventually surrendered.[12] In 1765, the British East India Company was granted the right to collect taxes from Bengal-Bihar. Eventually, in 1772, the East India company abolished local rule and took complete control of the province of Bengal-Bihar.[13] The battle exposed the inherent weaknesses and divisions among the Indian rulers. The lack of unity and coordination between the Nawabs and the Mughal Emperor made it easier for the British to overpower them. This further exacerbated the fragmentation of political power in India and paved the way for British imperialism.

Moreover, the Battle of Buxar and its aftermath fuelled resentment and resistance among the Indian population.[11] The oppressive policies and economic exploitation of the East India Company led to numerous uprisings and rebellions in the subsequent decades, most notably the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. These revolts were fuelled by the growing discontent over British rule and their exploitative practices. The Battle of Buxar had profound consequences for colonial India. It solidified British dominance in the region, eroded the authority of the Indian rulers, and sowed the seeds of future rebellions. The battle and its aftermath played a pivotal role in shaping the course of Indian history, setting the stage for nearly two centuries of British rule.

Gallery

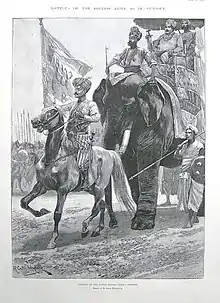

The Nawab of Bengal, Mir Qasim

The Nawab of Bengal, Mir Qasim Shuja-ud-Daula served as the leading Nawab Vizier of the Mughal Empire, he was lifelong of Shah Alam II.

Shuja-ud-Daula served as the leading Nawab Vizier of the Mughal Empire, he was lifelong of Shah Alam II.

References

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (2009). History Of The Freedom Movement In India (1857–1947). New Age International. p. 2. ISBN 9788122425765.

- John William (29 February 2004). Fortescue's History of the British Army -. Vol. 2. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-715-5.

- Parshotam Mehra (1985). A Dictionary of Modern History (1707–1947). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-561552-2.

- Zaman, Faridah (2015). "Colonizing the Sacred: Allahabad and the Company State, 1797-1857". The Journal of Asian Studies. 74 (2): 347–367 – via JSTOR.

- Cust, Edward (1858). Annals of the Wars of the Eighteenth Century: 1760–1783. Vol. III. London: Mitchell's Mibdglitiry Library. p. 113.

- Cadell, P. R. (1941). "560. The Battle of Buxar, 1764". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 20 (78): 113. JSTOR 44228260.

- Singh, Sonal (2017). "Micro-history Lost in a Global Narrative? Revisiting the Grant of the "Diwani" to the English East India Company". Social Scientist. 45 (3/4): 41–51 – via JSTOR.

- Black, Jeremy (28 March 1996). Wyse, Liz (ed.). The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492-1792. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-521-47033-9.

- Biddulph, H (1941). "571. THE BATTLE OF BUXAR, 1764". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. Society for Army Historical Research. 29 (79): 174 – via JSTOR.

- Cadell, P.R. (1941). "560. THE BATTLE OF BUXAR, 1764". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. Society for Army Historical Research. 20 (78): 113 – via JSTOR.

- Maharatna, Paramita (2012). "The Zamindars of Bihar: Their Resistance to Colonial Rule between 1765-1781". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress. 73: 1435 – via JSTOR.

- Bryant, G.J. (2004). "Asymmetric Warfare: The British Experience in Eighteenth-Century India". The Journal of Military History. 68 (2): 431–469 – via JSTOR.

- Keay, John (8 July 2010). The Honourable Company (Paperback ed.). London: HarperCollins UK. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-00-739554-5.