Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis (French: Crise de Fachoda), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French expedition to Fashoda on the White Nile sought to gain control of the Upper Nile river basin and thereby exclude Britain from Sudan. The French party and a British-Egyptian force (outnumbering the French by 10 to 1) met on friendly terms, but back in Europe it became a war scare. The British held firm as both empires stood on the verge of war with heated rhetoric on both sides. Under heavy pressure, the French withdrew, ensuring Anglo-Egyptian control over the area.

| Fashoda Incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scramble for Africa | |||||||

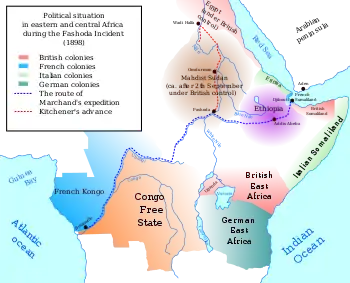

Map of Central and East Africa during the incident | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 132 soldiers | 1,500 British, Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

Background

During the late-19th century, Africa was rapidly being claimed and colonised by European colonial powers. After the 1885 Berlin Conference regarding West Africa, Europe's great powers went after any remaining lands in Africa that were not already under another European nation's influence. This period in African history is usually termed the Scramble for Africa by modern historiography. The principal powers involved in this scramble were Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Spain.

The French thrust into the African interior was mainly from the continent's Atlantic coast (modern-day Senegal) eastward, through the Sahel along the southern border of the Sahara, a territory covering modern-day Senegal, Mali, Niger, and Chad. Their ultimate goal was to have an uninterrupted link between the Niger River and the Nile, hence controlling all trade to and from the Sahel region, by virtue of their existing control over the caravan routes through the Sahara. France also had an outpost near the mouth of the Red Sea in French Somaliland (Now Djibouti), which could serve as an eastern anchor to an east–west belt of French territory across the continent.[1]

The British, on the other hand, wanted to link their possessions in Southern Africa (South Africa, Bechuanaland and Rhodesia), with their territories in East Africa (modern-day Kenya), and these two areas with the Nile basin. Sudan, which then included modern-day South Sudan and Uganda, was the key to the fulfilment of these ambitions, especially since Egypt was already under British control. This 'red line' (i.e. a proposed railway or road, see Cape to Cairo Railway) through Africa was made famous by the British diamond magnate and politician Cecil Rhodes, who wanted Africa "painted Red" (meaning under British control, since territories which were part of Britain were often coloured red on maps).[2]

If one draws a line from Cape Town to Cairo (Rhodes' dream) and another line from Dakar to French Somaliland (now Djibouti) by the Red Sea in the Horn (the French ambition), these two lines intersect in eastern South Sudan near the town of Fashoda (present-day Kodok), explaining its strategic importance. The French east–west axis and the British north–south axis could not co-exist; the nation that could occupy and hold the crossing of the two axes would be the only one able to proceed with its plan.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Fashoda had been founded by the Egyptian army in 1855 as a base from which to combat the East African slave trade. It was located on high ground along 160 kilometres (100 mi) of marshy shoreline at one of the few places where a boat could unload. The surrounding area, although swampy, was populated by Shilluk people, and by the mid-1870s, Fashoda was a bustling market and administrative town. The first Europeans to arrive in the region were explorers Georg Schweinfurth in 1869 and Wilhelm Junker in 1876. Junker described the town as "a considerable trading place ... the last outpost of civilization, where travelers plunging into or returning from the wilds of equatorial Africa could procure a few indispensable European wares from the local Greek traders." By the time Jean-Baptiste Marchand arrived, however, the deserted fort was in ruins.[3]

Fashoda was also bound up in the Egyptian Question, a long running dispute between the United Kingdom and France over the British occupation of Egypt. Since 1882 many French politicians, particularly those of the parti colonial, had come to regret France's decision not to join with Britain in occupying the country. They hoped to force Britain to leave, and thought that a colonial outpost on the Upper Nile could serve as a base for French gunboats. These in turn were expected to make the British abandon Egypt. Another proposed scheme involved a massive dam, cutting off the Nile's water supply and forcing the British out. These ideas were highly impractical, but they succeeded in alarming many British officials.[4]

Other European nations were also interested in controlling the upper Nile valley. The Italians got a head start from their Eritrean outpost at Massawa on the Red Sea, but their defeat by the Ethiopians at Adowa in March 1896 ended their attempt. In September 1896, King Leopold II, the Sovereign of the Congo Free State, dispatched a column of 5,000 Congolese troops, with artillery, towards the White Nile from Stanleyville on the Upper Congo River. They took five months to reach Lake Albert on the White Nile, about 800 kilometres (500 mi) from Fashoda, but by then, their soldiers were so angry at their treatment that they mutinied on 18 March 1897. Many of the Belgian officers were killed and the rest were forced to flee.[3]

Crisis

Marchand expedition

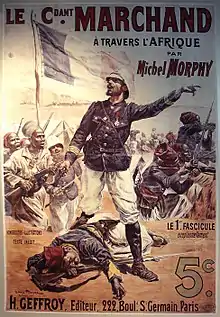

France made its move by sending Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, a veteran of the conquest of French Sudan, back to West Africa. He embarked a force composed mostly of West African colonial troops from Senegal on a ship for central Africa.[3] On 20 June 1896, he reached Libreville in the colony of Gabon with a force of only 120 tirailleurs plus 12 French officers, non-commissioned officers and support staff—Captain Marcel Joseph Germain, Captain Albert Baratier, Captain Charles Mangin, Captain Victor Emmanuel Largeau, Lieutenant Félix Fouqué, a teacher named Dyé, doctor Jules Emily Major, Warrant Officer De Prat, Sergeant George Dat, Sergeant Bernard, Sergeant Venail and the military interpreter Landerouin.[5]

Marchand's force set out from Brazzaville in a borrowed Belgian steamer with orders to secure the area around Fashoda and make it a French protectorate. They steamed up the Ubangi River to its head of navigation and then marched overland (carrying 100 tons of supplies, including a collapsible steel steamboat with a one-ton boiler[3]) through jungle and scrub to the deserts of Sudan. They travelled across Sudan to the Nile. They were to be met there by two expeditions coming from the east across Ethiopia, one of which, from Djibouti, was led by Christian de Bonchamps, veteran of the Stairs Expedition to Katanga.[5]

Following a difficult 14-month trek across the heart of Africa, the Marchand Expedition arrived on 10 July 1898, but the de Bonchamps Expedition failed to make it after being ordered by the Ethiopians to halt, and then suffering accidents in the Baro Gorge. Marchand's small force thus became isolated and alone.[6] The British, meanwhile, were engaged in the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan, moving upriver from Egypt. On 18 September a flotilla of five British gunboats arrived at the isolated Fashoda fort. They carried 1,500 British, Egyptian and Sudanese soldiers, led by Sir Herbert Kitchener and including Lieutenant-Colonel Horace Smith-Dorrien.[7] Marchand had received incorrect reports that the approaching force consisted of Dervishes but now found himself facing a diplomatic rather than a military crisis.[8]

Standoff at Fashoda

Both sides insisted on their right to Fashoda but agreed to wait for further instructions from home.[9] The two commanders behaved with restraint and even a certain humour. Kitchener toasted Marchand with whisky, the drinking of which the French officer described as "one of the greatest sacrifices I ever made for my country". Kitchener inspected a French garden commenting "Flowers at Fashoda. Oh these Frenchmen!" More seriously the British distributed French newspapers detailing the political chaos caused by the Dreyfus affair, warning that France was in no condition to provide serious support for Marchand and his party.[10] News of the meeting was relayed to Paris and London, where it inflamed the pride of both nations. Widespread popular outrage followed, each side accusing the other of naked expansionism and aggression. The crisis continued throughout September and October 1898. The Royal Navy drafted war orders and mobilized its reserves.[11]

French withdrawal

.png.webp)

As the commander of the Anglo-Egyptian army that had just defeated the forces of the Mahdi at the Battle of Omdurman, Kitchener was in the process of reconquering the Sudan in the name of the Egyptian Khedive, and after the battle he opened sealed orders to investigate the French expedition. Kitchener landed at Fashoda wearing an Egyptian Army uniform and insisted in raising the Egyptian flag at some distance from the French flag.

In naval terms, the situation was heavily in Britain's favour, a fact that French deputies acknowledged in the aftermath of the crisis. Several historians have given credit to Marchand for remaining calm.[12] The military facts were undoubtedly important to Théophile Delcassé, the newly appointed French foreign minister. "They have soldiers. We only have arguments," he said resignedly. In addition, he saw no advantage in a war with the British, especially since he was keen to gain their friendship in case of any future conflict with Germany. He therefore pressed hard for a peaceful resolution of the crisis although it encouraged a tide of nationalism and anglophobia. In an editorial published in L'Intransigeant on 13 October Victor Henri Rochefort wrote, "Germany keeps slapping us in the face. Let's not offer our cheek to England."[13] As Professor P. H. Bell writes,

Between the two governments there was a brief battle of wills, with the British insisting on immediate and unconditional French withdrawal from Fashoda. The French had to accept these terms, amounting to a public humiliation.[14]

Aftermath

According to French nationalists, France's capitulation was clear evidence that the French army had been severely weakened by the traitors who supported Dreyfus. Yet the reopening of the Dreyfus affair in January had done much to distract French public opinion from events in Sudan and with people increasingly questioning the wisdom of a war over such a remote part of Africa, the French government quietly ordered its soldiers to withdraw on 3 November and the crisis ended peacefully.[15] Marchand chose to withdraw his small force by way of Abyssinia and Djibouti, rather than cross Egyptian territory by taking the relatively quick journey by steamer down the Nile.[16]

It was a diplomatic victory for the British as the French realized that in the long run they needed the friendship of Britain in case of a war between France and Germany.[17]

In March 1899, the Anglo-French Convention of 1898 was signed and it was agreed that the source of the Nile and the Congo rivers should mark the frontier between their spheres of influence.

The Fashoda Incident was the last serious colonial dispute between Britain and France, and its classic diplomatic solution is considered by most historians to be the precursor of the Entente Cordiale of 1904.[18] The two main individuals involved in the incident are commemorated in the Pont Kitchener-Marchand, a 116-metre (381 ft) road bridge over the Saône, completed in 1959 in the French city of Lyon.[19] In 1904, Fashoda was officially renamed Kodok. It is located in modern-day South Sudan.

Legacy

The incident gave rise to the 'Fashoda syndrome' in French foreign policy, or seeking to assert French influence in areas which might be becoming susceptible to British influence.[15] As such it was used as a comparison to other later crises or conflicts such as the Levant Crisis of 1945,[20] the Nigerian Civil War in Biafra in the 1970s and the Rwandan Civil War in 1994.[21]

See also

Citations

- William Roger Louis, and Prosser Gifford, eds. France and Britain in Africa: imperial rivalry and colonial rule (Yale University Press, 1971).

- Louis and Gifford, eds. France and Britain in Africa: imperial rivalry and colonial rule (1971).

- Jones, Jim, "The Fashoda Incident" West Chester University, 2014; Web, 12 July 2014; accessed 2019.10.20.

- Henri L. Wesseling, Divide and conquer: The partition of Africa, 1880–1914 (1996).

- Michel Côte, Mission de Bonchamps: Vers Fachoda à la rencontre de la mission Marchand à travers l’Ethiopie, Paris, Plon, 1900.

- Lewis 1988, pp. 133–135, 210.

- Pakenham 1991, p. 548.

- Pakenham 1991, p. 547.

- Moorehead 2002, p. 78.

- Tombs, Robert and Isabelle (2006). That Sweet Enemy. The French and the British From the Sun King to the Present. Random House. p. 429. ISBN 0-434-00867-2.

- Pakenham 1991, p. 552.

- Giffen 1930, pp. 79–98.

- Vaïsse 2004, pp. 15–16.

- Bell 2014a, p. 3.

- Langer 1951, pp. 537–580.

- Pakenham 1991, p. 555.

- Taylor 1954, pp. 321–326.

- Horne 2006, pp. 298–299.

- "Kitchener-Marchand Bridge (Lyon, 1949)". Structurae.

- Bell 2014b, p. 76.

- Schmidt 2013, p. 181.

General and cited references

- Andrew, G.; et al. (1974). "Gabriel Hanotaux, the Colonial Party and the Fashoda Strategy". J. Imp. Commonw. Hist. 3 (1): 55–104. doi:10.1080/03086537408582422.

- Bates, D. (1984). The Fashoda Incident of 1898: Encounter on the Nile. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192117718.

- Bell, P. (2014a). France and Britain, 1900–1940: Entente and Estrangement. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781317892731.

- Bell, P. M. H (2014b). France and Britain, 1940–1994: The Long Separation. Routledge. ISBN 9781317888413.

- Berenson, Edward H (2010). Heroes of Empire: Five charismatic men and the conquest of Africa. University of California Press.

- Brown, R. (1970). Fashoda Reconsidered: The Impact of Domestic Politics on French Policy in Africa, 1893–1898. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801810985.

- Churchill, W. (1899). The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan. London: Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 2704682.

- Eubank, K. (1960). "The Fashoda Crisis Re-Examined". Historian. 22 (2): 145–162. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1960.tb01649.x.

- Giffen, M. (1930). Fashoda, the Incident and Its Diplomatic Setting. University of Chicago Press. OCLC 993310905.

- Horne, A. (2006). La Belle France: A Short History. New York: Vintage. ISBN 9781400034871.

- Langer, W. (1951). The Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1890–1902. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 787805.

- Lewis, D. (1988). The Race to Fashoda: European Colonialism & African Resistance in the Scramble for Africa. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747501138.

- Moorehead, A. (2002). The White Nile. London: Penguin. ISBN 9780141391168.

- Pakenham, T. (1991). The Scramble for Africa, 1876–1912. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780394515762.

- Porter, C. (1975). The Career of Théophile Delcassé. Westport: Greenwood. pp. 132–139. ISBN 9780837177205.

- Riker, T. (1979). "A Survey of British Policy in the Fashoda Crisis". Political Science Quarterly. 44 (1): 54–78. doi:10.2307/2142814. JSTOR 2142814.

- Schmidt, Elizabeth (2013). Foreign Intervention in Africa: From the Cold War to the War on Terror Issue 7 of New Approaches to African History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521882385.

- Taylor, A. (1950). "Prelude to Fashoda: The Question of the Upper Nile, 1894–5". English Historical Review. 65 (254): 52–80. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxv.ccliv.52.

- Taylor, A. (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 123580339.

- Turton, E. R. (1976). "Lord Salisbury and the Macdonald Expedition". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 5 (1): 35–52. doi:10.1080/03086537608582472.

- Vaïsse, M. (2004). L'Entente cordiale de Fachoda à la Grande Guerre: dans les archives du Quai d'Orsay (in French). Brussels: Éditions Complexe. ISBN 9782804800062.

- Wright, Patricia (August 1972). "The French Fashoda Expedition 1896–99". History Today. Vol. 22, no. 8. pp. 564–575.

- Wright, Patricia (1972). Conflict on the Nile: The Fashoda Incident of 1898. London: Heinemann. ISBN 9780434878307. OCLC 185779517.

Further reading

- Roberts, T. (2020). "The Comite de L'Afrique Francaise, the Chad Plan, and the Origins of Fashoda". The Historical Journal. 64 (2): 310–331. doi:10.1017/S0018246X20000023. S2CID 219078894.

External links

Media related to Fashoda Incident at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fashoda Incident at Wikimedia Commons