Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition of 1887 to 1889 was one of the last major European expeditions into the interior of Africa in the nineteenth century. Led by Henry Morton Stanley, its goal was ostensibly the relief of Emin Pasha, the besieged Egyptian governor of Equatoria (part of modern-day South Sudan), who was threatened by Mahdist forces.

Stanley set out to traverse the continent with a force of nearly 700 men, navigating up the Congo River and then through the Ituri rainforest to reach East Africa. The arduous journey caused Stanley to split the expedition into two columns; the advance column eventually reached Emin Pasha in July 1888. A series of mutinies, disagreements, and miscommunications forced Stanley and Emin to withdraw from Equatoria in early 1889.

The expedition was initially celebrated for its ambition in crossing "Darkest Africa". However, soon after Stanley returned to Europe, it gained notoriety for the deaths of so many of its members, widespread reports of brutality, and the disease unwittingly left in its wake. It was the last large-scale private expedition undertaken as part of the Scramble for Africa.

Background

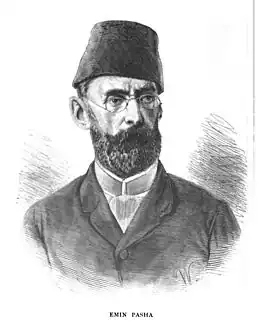

With the capture of Khartoum by the Mahdists (followers of Islamic religious leader Muhammad Ahmad) in 1885, the Ottoman-Egyptian administration of Sudan collapsed. Equatoria, the extreme southern province of the Sudan, was nearly cut off from the outside world, as it was located on the upper reaches of the Nile near Lake Albert. Emin Pasha was a German Jewish-born Ottoman doctor and naturalist who had been appointed Governor of Equatoria by Charles George Gordon, the British general who himself had attempted to relieve Khartoum. Emin, able to send and receive letters via Buganda and Zanzibar, had been informed in February 1886 that the Egyptian government would abandon Equatoria. In July, he was encouraged by missionary Alexander Mackay to invite the British government to annex Equatoria itself. The government was not interested in such a doubtful venture, but the British public came to see Emin as a second General Gordon, in mortal danger from the Mahdists.

Scottish businessman and philanthropist William Mackinnon had been involved in various colonial ventures, and by November he had approached Stanley about leading a relief expedition. Stanley declared himself ready "at a moment's notice" to go. Mackinnon then approached J. F. Hutton, a business acquaintance also involved in colonial activities, and together they organized the "Emin Pasha Relief Committee", mostly consisting of Mackinnon's friends, whose first meeting was on 19 December 1886. The Committee raised a total of about £32,000.

Stanley was officially still in the employment of Leopold II of Belgium, by whom he had been employed in carving out Leopold's 'Congo Free State'. As a compromise for letting Stanley go, it was arranged in a meeting in Brussels between Stanley and the king, that the expedition would take a longer route up the Congo River, contrary to plans for a shorter route inland from the eastern African coast. In return, Leopold would provide his Free State steamers for the transportation of the expedition up the river, from Stanley Pool (now Pool Malebo) as far as the mouth of the Aruwimi River.

By 1 January 1887, Stanley was back in London preparing the expedition to widespread public acclaim. Stanley himself was intent that the expedition be one of humanitarian assistance rather than of military conquest. He declared:

The expedition is non-military—that is to say, its purpose is not to fight, destroy, or waste; its purpose is to save, to relieve distress, to carry comfort. Emin Pasha may be a good man, a brave officer, a gallant fellow deserving of a strong effort of relief, but I decline to believe, and I have not been able to gather from any one in England an impression, that his life, or the lives of the few hundreds under him, would overbalance the lives of thousands of natives, and the devastation of immense tracts of country which an expedition strictly military would naturally cause. The expedition is a mere powerful caravan, armed with rifles for the purpose of insuring the safe conduct of the ammunition to Emin Pasha, and for the more certain protection of his people during the retreat home. But it also has means of purchasing the friendship of tribes and chiefs, of buying food and paying its way liberally.

Purpose of expedition

In a number of publications made after the expedition, Stanley asserted that the singular purpose of the effort was to offer relief to Emin Pasha.

The advantages of the Congo route were about five hundred miles shorter land journey, and less opportunities for deserting. It also quieted the fears of the French and Germans that, behind this professedly humanitarian quest, we might have annexation projects.

— Henry Morton Stanley, The Autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley[2]

However, Stanley's other writings point to a secondary goal — territorial annexation. In his account of the expedition, he implied that his meeting with the Sultan of Zanzibar was in regards to British interests in East Africa. These interests were threatened not only by the Mahdists, but also by German imperial ambitions in the region; Germany would not recognize British suzerainty over Zanzibar (and its continental holdings) until 1890.

I have settled several little commissions at Zanzibar satisfactorily. One was to get the Sultan to sign the concessions which Mackinnon tried to obtain a long time ago. As the Germans have magnificent territory east of Zanzibar, it was but fair that England should have some portion for the protection she has accorded to Zanzibar since 1841 ... The concession that we wished to obtain embraced a portion of East African coast, of which Mombasa and Melindi were the principal towns. For eight years, to my knowledge, the matter had been placed before His Highness, but the Sultan's signature was difficult to obtain.

— Henry Morton Stanley, In Darkest Africa[3]

The records at the National Archives at Kew, London, offer an even deeper insight and show that annexation was a purpose he had been aware of for the expedition. This is because there are a number of treaties curated there (and gathered by Stanley himself from what is present day Uganda during the Emin Pasha Expedition), ostensibly gaining British protection for a number of African chiefs. Amongst these were a number that have long been identified as possible frauds.[4] A good example is treaty number 56, supposedly agreed upon between Stanley and the people of "Mazamboni, Katto, and Kalenge". These people had signed over to Stanley "the Sovereign Right and Right of Government over our country for ever in consideration of value received and for the protection he has accorded us and our Neighbours against KabbaRega and his Warasura".[5]

Preparations

The expedition was planned to go to Cairo, then to Zanzibar to hire porters, then south of Africa, around the Cape to the mouth of the Congo, up the Congo by Leopold's steamers, branching off at the Aruwimi River. Stanley intended to establish a camp on the Aruwimi, then go east overland through unknown territory to reach Lake Albert and Equatoria. He then expected that Emin would send the families of Emin's Egyptian employees back along the just-pioneered route, along with a large store of ivory accumulated in Equatoria, while Stanley, Emin, and Emin's soldiers would proceed eastward to Zanzibar. Coincidentally, public doubts over the plan centered around whether it could be achieved; the possibility that Emin might not want to leave seems not to have been considered.

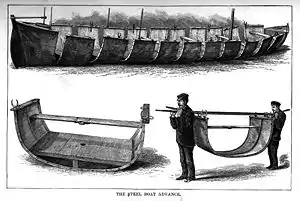

The expedition was the largest and best-equipped to go to Africa; a 28-foot steel boat named the Advance was designed to be divided into 12 sections for carrying over land, and Hiram Maxim presented the expedition with one of his recently invented Maxim guns, which was the first to be brought to Africa. Merely 'exhibiting' the gun was thought to be a scare, which would spare the expedition problems with hostile natives.

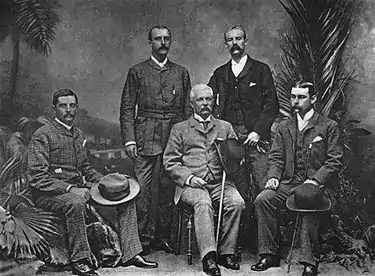

The Relief Committee received 400 applications by hopeful participants. From these, Stanley chose the officers who were to accompany him to Africa:

- James Sligo Jameson, John Rose Troup, and Herbert Ward had all travelled in Africa before, Jameson as a big game hunter, artist, and traveller, and Troup and Ward as employees of the Congo Free State.

- Robert H. Nelson, William Bonny, William G. Stairs, and Edmund Barttelot were all military men. Barttelot had been doing service in India.

- A. J. Mounteney-Jephson was a young 'gentleman of leisure' coming from the merchant marine who was hired on the quality of his face only, but he paid £1,000 to the Relief Committee, as did Jameson, in order to participate in the expedition.

- The expedition's doctor Thomas Heazle Parke was hired at the last minute, while the expedition was already en route, in Alexandria, where he was doing military service.

- William Hoffmann was Stanley's personal servant, curiously enough scarcely mentioned at all in Stanley's own account of the events.

Stanley departed London on 21 January 1887 and arrived in Cairo on 27 January. Egyptian objections to the Congo route were overridden by a telegram from Lord Salisbury, and the expedition was permitted to march under the Egyptian flag. Stanley also met with Mason Bey, Schweinfurth, and Junker, who had more up-to-date information about Equatoria.

Stanley left Cairo on 3 February, joined up with expedition members during stops in Suez and Aden, and arrived in Zanzibar on 22 February. The next three days were spent packing for the expedition, loading the Madura, and negotiating. Stanley acted as a representative of Mackinnon in convincing the Sultan of Zanzibar to grant a concession for what later became the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC), and made two agreements with Tippu Tib. The first included appointing him as Governor of Stanley Falls, an arrangement much criticized in Europe as a deal with a slave-trader, and the second agreement regarded the provisions of carriers for the expedition. In addition to transporting stores, the carriers were now also expected to bring out some 75 tons of ivory stored in Equatoria. Stanley posted letters to Emin predicting his arrival on Lake Albert around August.

Up the Congo

The expedition left Zanzibar on 25 February and, rounding the Cape of Good Hope, arrived at Banana at the mouth of the Congo on 18 March. Their arrival was somewhat unexpected, because a telegraph cable had broken and local officials had received no instructions. Chartered steamers brought the expedition to Matadi, where the carriers took over, bringing some 800 loads of stores and ammunition to Leopoldville on the Stanley Pool. Progress was slow, since the rainy season was at its height, and food was short – a problem that was to be persistent throughout the expedition (the area along the route rarely had spare food for 1,000 hardworking men, as it was a subsistence economy).

On 21 April, the expedition arrived at Leopoldville. King Leopold had promised a flotilla of river steamers, but only one worked: the Stanley. Stanley requisitioned two (Peace and Henry Reed) from missionaries of the Baptist Mission and the Livingstone Inland Mission, whose protests were overridden, as well as the Florida, which was still under construction and so used as a barge. Even these were insufficient, so many of the stores were left at Leopoldville and more at Bolobo. At this point, Stanley also announced the division of the expedition: a "Rear Column" would encamp at Yambuya on the Aruwimi, while the "Advance Column" pressed on to Equatoria.

The voyage up the Congo started 1 May and was generally uneventful. At Bangala Station, Barttelot and Tippu Tib continued up to Stanley Falls in the Henry Reed, while Stanley took the Aruwimi to Yambuya. The inhabitants of Yambuya refused permission to reside in their village, so Stanley attacked and drove the villagers away, turning the deserted village into a fortified camp. Meanwhile, at Stanley Falls, Tippu Tib attempted to acquire carriers, but he believed that Stanley had broken his part of their agreement by leaving ammunition behind, and Barttelot came to Yambuya with only an indefinite promise that carriers would arrive in several weeks.

Traversing the Ituri Rainforest

Stanley, however, insisted on speed, and left for Lake Albert on 28 June, originally expecting to take two months. The Advance Column, however, was unprepared for the extreme difficulties of travel through the Ituri rainforest and did not reach the lake until December. Only 169 of the 389 who set out from Yambuya were still alive. The trees of the forest were so tall and dense that little light reached the floor, food was scarcely to be found, and the local Pygmies took the expedition for an Arab raiding party, shooting at them with poisoned arrows. The expedition stopped at two Arab settlements, Ugarrowwa's and Ipoto, in each case leaving more of their equipment behind in exchange for food.

The forest eventually gave way to grassland, and on 13 December the expedition was looking down on Lake Albert. However, Emin was not there, and the locals had not seen a European in many years. Stanley decided to return to the village of Ibwiri on the plateau above the lake, where they built Fort Bodo. Stairs went back to Ipoto to collect men and equipment, and returned 12 February. A second trip went back to Ugarrowwa's to collect more equipment. Meanwhile, on 2 April Stanley returned to Lake Albert, this time with the Advance. On 18 April they received a letter from Emin, who had heard about the expedition a year earlier, and had come down the lake in March after hearing rumors of Stanley's arrival.

Stanley meets Emin

Jephson was sent on ahead to the lake with the Advance, took the boat up to Mswa, and met Emin on 27 April 1888. Emin brought his steamer to the south end of the lake, and met Stanley there on the 29th, who was surprised to find the figure of Emin to have "not a trace on it of ill-health or anxiety", and celebrated with three bottles of champagne that had been carried all the way up the Congo. Emin provided Stanley with food and other supplies, thus rescuing the rescuers.

At this point things became difficult. Emin was primarily interested in ammunition and other supplies, and a communications route, all of which would assist him in remaining in Equatoria, while Stanley's main goal was to bring Emin out. A month of discussion produced no agreement, and on 24 May Stanley went back to Fort Bodo, arriving there 8 June and meeting Stairs, who had returned from Ugarrowwa's with just fourteen surviving men. On the way Stanley saw the Ruwenzori Mountains for the first time (although Parke and Jephson had seen them on 20 April).

Fate of the Rear Column

On 16 June, Stanley left the fort in search of the Rear Column; no word of or from them had been received in a long time. Finally, on 17 August at Banalya, 90 miles upstream from Yambuya, Stanley found Bonny, the sole European left in charge of the Column, along with a handful of starving carriers. Barttelot had been shot in a dispute, Jameson was at Bangala dying of a fever, Troup had been invalided home, and Herbert Ward had gone back down the Congo a second time to telegraph the Relief Committee in London for further instructions (the Column had not heard from Stanley in over a year). The original purpose of the Rear Column – to wait for the additional carriers from Tippu Tib – had not been accomplished, since without the ammunition supplied by the expedition, Tippu Tib had nothing with which to recruit. After several side trips, Barttelot decided to send Troup and the others on the sick list down the Congo, and 11 June 1888, after the arrival of a group of Manyema bringing Barttelot's total to 560, set off in search of Stanley.

But the march soon disintegrated into chaos, with large-scale desertion and multiple trips to try to bring up stores; then on 19 July Barttelot was shot while trying to interfere with a Manyema festival. Jameson decided to go down to Bangala to bring up extra loads and left on 9 August, shortly before Stanley's arrival. Stanley was incensed at the state of the Rear Column, blaming them for lack of motion despite his previous orders that they wait for him at Yambuya. From surviving officers Stanley also heard stories of Barttelot's brutality and of another officer, James Sligo Jameson, who was alleged to have purchased a young female slave and given her to cannibals so he could record her being killed and eaten.[6] In his posthumously published diary, Jameson admitted that he had indeed paid for the girl and watched as she was butchered, but claimed that he considered the whole affair a joke and had not expected her to actually be killed.

I sent my boy for six handkerchiefs, thinking it was all a joke ..., but presently a man appeared, leading a young girl of about ten years old at the hand, and I then witnessed the most horribly sickening sight I am ever likely to see in my life. He plunged a knife quickly into her breast twice, and she fell on her face, turning over on her side. Three men then ran forward, and began to cut up the body of the girl; finally her head was cut off, and not a particle remained, each man taking his piece away down to the river to wash it. The most extraordinary thing was that the girl never uttered a sound, nor struggled, until she fell. Until the last moment, I could not believe that they were in earnest... that it was anything save a ruse to get money out of me.... When I went home I tried to make some small sketches of the scene while still fresh in my memory, not that it is ever likely to fade from it. No one here seemed to be in the least astonished at it."[7]

According to the testimony of Jameson's colleague William Bonny, Jameson must have stayed around to watch while the girl was cooked and consumed, since the last of his six sketches (which he had shown Bonny) "represents the feast."[8] The "six handkerchiefs" Jameson had paid were indeed valuable enough to purchase a child slave, and Jameson's diary also shows that he was well informed of cannibal customs and had even seen remainders of a cannibal meal before, making his line of defense doubtful.[9]

After the dispatch of a number of letters down-Congo, the expedition returned to Fort Bodo, taking a different route that proved no better for food supply, and it reached the Fort on 20 December, now reduced to 412 men, of whom 124 were too ill to carry any loads. On 16 January 1889, near Lake Albert, Stanley received letters from Emin and Jephson, who had been made prisoner by Emin's officers for several months, while at the same time the Mahdists had been capturing additional stations of Equatoria. Since Stanley's arrival, numerous rumours had gone around about Emin's intentions and the likely fate of the soldiers, and in August of the previous year matters had come to a head; a number of officers rebelled, deposed Emin as governor, and kept him and Jephson under a sort of house arrest in Dufile until November. Even so, Emin was still reluctant to abandon the province.

Withdrawal to the coast

By 17 February all the surviving members of the expedition, and Emin with a group of about 65 loyal soldiers, met at Stanley's camp above Lake Albert, and during the subsequent weeks several hundred more of Emin's followers, many of them the families of the soldiers, assembled there. Emin still had not expressed a firm intention to leave Equatoria, and 5 April, after a heated argument, Stanley determined to leave shortly, and the expedition departed Kavalli's for the coast on 10 April.

The trip to the coast passed first south, along the western flank of the Ruwenzoris, and Stairs attempted to ascend to a summit, reaching 10,677 ft before having to turn around. They then passed by Lake Edward and Lake George, then across to the southernmost point of Lake Victoria, passing through the kingdoms of Ankole and Karagwe. Stanley made "treaties" with the various rulers; although it is most likely that these were not regarded as such by the locals, they were later used to establish IBEAC claims in the area.

Lake Victoria was seen on 15 August, and the expedition reached Mackay's missionary station at Usambiro on 28 August. At this point they began to learn of the complicated changing situation in East Africa, with European colonial powers scrambling to stake their claims, and a second relief expedition under Frederick John Jackson. After waiting fruitlessly for news of the Jackson expedition, Stanley left on 17 September, with a party now reduced to some 700 by a combination of death and desertion.

As the expedition approached the coast, they encountered parties of Germans and other signs of German activity in the interior, and were met by commissioner Wissmann on 4 December and escorted into Bagamoyo. That evening a banquet was held, during which an inebriated Emin fell out of a second-storey window he mistook for a balcony, and from which he did not recover until the end of January 1890. In the meantime, the rest of the expedition had dispersed; Stanley went to Zanzibar and then to Cairo, where he wrote the 900 pages of In Darkest Africa in just 50 days. The Zanzibari carriers were paid off or (in the case of prisoners) returned to their masters, the Sudanese and Egyptians were transported back to Egypt, some later returning to work for the IBEAC. Emin took service with the Germans in February, and the other Europeans returned to England.

Aftermath

Stanley returned to Europe in May 1890 to tremendous public acclaim; both he and his officers received numerous awards, honorary degrees, and speaking engagements. In June alone his newly published book sold 150,000 copies. But the adulation was to be short-lived.

By autumn, as the true cost of the expedition became known, and as the families of Barttelot and Jameson reacted to Stanley's accusations of incompetence in the Rear Column, criticism and condemnation became widespread. Samuel Baker called the story of the Rear Column "the most horrible and indecent exposure that I have ever heard of seen in print".[10] Stanley's own use of violence during the expedition also revived old criticisms that he was a "sham explorer" as well as doubts over the supposed humanitarian value of European exploration in Africa.[10] In the end, the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition came to be the last expedition of its type; future African expeditions would be government-run in pursuit of military or political goals, or conducted purely for science.

An Anglo-Egyptian force under Lord Kitchener managed to reconquer Sudan from the Mahdists in 1899. Equatoria was incorporated as part of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, nominally under British administration, though it remained isolated and underdeveloped well into the 20th century.

From 1898 to 1900, a devastating sleeping sickness epidemic spread into territories that are now Democratic Republic of the Congo, western Uganda and south of Sudan. Native cattle traveling with the expedition may have introduced the parasite into previously-unaffected regions.[11] However, not all authors agree.[12]

In popular culture

It has been suggested that stories of the expedition — in particular, the disastrous plight of the "rear column" — inspired Joseph Conrad in his 1899 novella Heart of Darkness. Critic Adam Hochschild suggests that the character of Kurtz, the isolated and insane Congo trader, was modeled on Barttelot, who "went mad, began hitting, whipping, and killing people, and was finally murdered".[13] Harold Bloom also connected the portrayal of Kurtz with the figures of Stanley and Tippu Tib.[14]

The fate of the Rear Column is the subject of Simon Gray's 1978 play The Rear Column, which features Barttelot, Jameson, Ward, Bonny, Troup and Stanley as characters.

References

- Headley, Joel (1890). Stanley's Adventures in the Wilds of Africa. Edgewood.

- Stanley, Henry (1909). The Autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 355.

- Stanley, Henry (1891). In Darkest Africa. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 69.

- J. M. Gray, "Early Treaties in Uganda, 1888-1891", The Uganda Journal, The Journal of the Uganda Society, 2:1 (1948), 30

- British National Archives, Kew (BNA) FO 2/139 (Treaty number 56, undated).

- Jeal, T, Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa's Greatest Explorer, Yale University Press, 2007, pp. 357-358.

- Jameson, James S. (1891). The Story of the Rear Column of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. New York: National Publishing. p. 291.

- Siefkes, Christian (2022). Edible People: The Historical Consumption of Slaves and Foreigners and the Cannibalistic Trade in Human Flesh. New York: Berghahn. p. 160.

- Siefkes 2022, p. 157, 161.

- Kennedy, Dane (2013-03-01). The Last Blank Spaces. Harvard University Press. p. 264. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674074972. ISBN 978-0-674-07497-2.

- Parry, Eldryd H. O. (2008-04-15). "Book Review". Brain. 131 (5): awn069. doi:10.1093/brain/awn069.

- Lyons, Maryinez (2002-06-30). The Colonial Disease. Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0-521-52452-0.

- Hochschild, Adam: King Leopold's Ghost. New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998, pp. 98; 145,

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2009). Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. Infobase Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-1438117102.

Further reading

- Primary sources

- Jameson, James S. (1891). The Story of the Rear Column of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition. New York: National Publishing.

- Jephson, A. J. Mounteney (1969). Diary, Edited by Dorothy Middleton, Hakluyt Society.

- Stanley, Henry Morton (1890). In Darkest Africa.

- Secondary works

- Liebowitz, Daniel; Pearson, Charles (2005). The last expedition (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05903-0.

- Moorehead, Alan. The White Nile. London.

- Smith, Iain R. (1972). The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition 1886-1890. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gould, Tony (1979). In Limbo: the story of Stanley's rear column. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-10125-5.

- Fiction

- Forbath, Peter (1988). The Last Hero. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0671242857.

External links

![]() Media related to Emin Pasha Relief Expedition at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Emin Pasha Relief Expedition at Wikimedia Commons