Anastasio Bustamante

Trinidad Anastasio de Sales Ruiz Bustamante y Oseguera (Spanish pronunciation: [anasˈtasjo βustaˈmante]; 27 July 1780 – 6 February 1853) was a Mexican physician, general, and politician who served as the 4th President of Mexico three times from 1830 to 1832, 1837 to 1839, and 1839 to 1841. He also served as the 2nd Vice President of Mexico from 1829 to 1832 under Presidents Vicente Guerrero, José María Bocanegra, himself, and Melchor Múzquiz. He participated in the Mexican War of Independence initially as a royalist before siding with Agustín de Iturbide and supporting the Plan of Iguala.

Anastasio Bustamante | |

|---|---|

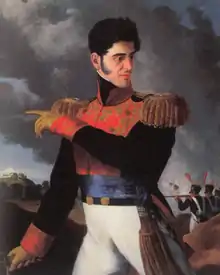

Portrait of Bustamante, 1830-32 | |

| 4th President of Mexico | |

| In office 1 January 1830 – 13 August 1832 | |

| Vice President | Himself |

| Preceded by | José María Bocanegra |

| Succeeded by | Melchor Múzquiz |

| In office 19 April 1837 – 20 March 1839 | |

| Preceded by | José Justo Corro |

| Succeeded by | Antonio López de Santa Anna |

| In office 19 July 1839 – 22 September 1841 | |

| Preceded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| Succeeded by | Francisco Javier Echeverría |

| 2nd Vice President of Mexico | |

| In office 11 June 1829 – 23 December 1832 | |

| President | Vicente Guerrero José María Bocanegra Executive Trimuvate (of Pedro Vélez, Lucas Alaman, and Luis Quintanar) Himself Melchor Múzquiz |

| Preceded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Trinidad Anastasio de Sales Ruiz Bustamante y Oseguera 27 July 1780 Jiquilpan, New Spain |

| Died | 6 February 1853 (aged 72) San Miguel de Allende, Mexico |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Signature | |

Bustamante was a member of the Provisional Government Junta, the first governing body of Mexico. After the fall of the First Mexican Empire, his support for Emperor Iturbide was pardoned by President Guadalupe Victoria. The controversial 1828 general election sparked riots forcing the results to be nullified, as a result, Congress named him vice president while the liberal Vicente Guerrero was named president. Bustamante's command of a military reserve during the Barradas Expedition in 1829 allowed him to launch a coup d'état ousting Guerrero.

During his first term as president, he expelled U.S. Minister Joel Roberts Poinsett, issued a law prohibiting American immigration to Texas, and produced a budget surplus. His leading minister during this time was the conservative intellectual Lucas Alamán. Opponents of his regime proclaimed the Plan of Veracruz in 1832, leading to almost a year of civil war, ultimately forcing Bustamante into exile.

During his exile, the First Republic collapsed and was replaced by Santa Anna with the Centralist Republic of Mexico. Santa Anna's fall from power during the Texas Revolution in 1836 gave Bustamante the chance to return to Mexico and smoothly reassume the presidency in early 1837. Refusal to compensate French losses in Mexico resulted in the disastrous Pastry War in late 1838. Bustamante briefly stepped down in 1839 to suppress a rebellion led by José de Urrea. Relations with the United States were restored and treaties signed with European powers. Rebellions in favor of restoring the federal system and an ongoing financial crisis was leading to unrest all over the nation. The state of Yucatán broke away in 1839, and in 1840 Bustamante himself was taken hostage in the capital by federalist rebels who were ultimately defeated. A conservative revolt led by Mariano Paredes ultimately forced him into a second exile in 1841. Bustamante returned in 1845 and participated in the Mexican–American War. He spent his last years in San Miguel de Allende where he died in 1853.

Early life

Anastasio Bustamante was born on July 27, 1780, in Jiquilpan, Michoacán to Jose Ruiz Bustamante and Francisca Oseguera. His family did not have great wealth and his father was employed transporting snow to Guadalajara, nonetheless they provided the young Anastasio with a good education. At the age of fifteen he enrolled at the Seminary College of Guadalajara, sponsored by Marcelino Figueroa, curate of the village of Tuxpam. He then went to Mexico City to study medicine with Dr. Ligner professor of chemistry at the college of mining. After graduating he accepted an offer to work at San Luis Potosí and was made director of the hospital of San Juan de Dios.[1]

Ever since his college years, Bustamante had also shown an intention of joining the military and after the upheavals suffered by Spain in 1808 as a consequence of the Peninsular War a corp of cavalry was formed in San Luis Potosí made up of the leading families and Bustamante was named a member, but he did not leave his profession as a physician until the Mexican War of Independence broke out in September 1810, at which Bustmante found himself fighting as a Spanish loyalist under the command of Felix Calleja.[1]

Military career

War of Independence

He was promoted to captain in 1812 and found himself at the Siege of Cuautla in which he was commissioned by Calleja to break the siege. He then found himself seeing action in the Valley of Apam where he was wounded in action. He was recruited to the regiments of Pascual Liñán and sent to repulse the invasion started at Galveston by Javier Mina.[1]

He captured the Fort of Remedios where he took the batteries in spite of being wounded and pursued the fleeing insurgents with cavalry. He helped pacify the entire province of Guanajuato culminating in the battle at the Hacienda de Guanimaro in which he routed the forces of Torres and the American filibuster Gregorio Wolf.[2]

Towards the end of the war Bustamante found himself at the Hacienda de Pantoja in charge of operations at the Valle of Santiago when Captain Quintanilla on behalf of Agustín de Iturbide attempting to recruit him to join the Plan of Iguala to which Bustamante aquieced.[2]

The viceroy had given orders to the commandant general of the province Antonio Linares that Bustamante be withdrawn from his command, but Bustamante intercepted the message, and he proclaimed his support for independence on March 19, 1821. He traveled to Celaya where he offered to Linares the command post which he rejected, he entered Guanajuato without meeting any resistance, and he removed from the Alhondiga the bodies of the insurgents who had been executed for fighting for independence at the start of the war, moving them rather to the cemetery of San Sebastián.[2]

Iturbide designated Bustamante second in command in regards to the revolution, and he accompanied him to a conference with General Cruz at the Hacienda of San Antonio. Bustamante was then declared head of all cavalry, defeating the forces of Bracho and San Julian who marched to the relief of Querétaro.[2]

Iturbide meanwhile travelled to Puebla and Bustamante advanced through Arroyazarco to the outskirts of the capital to prepare the siege and fought at Azcapotzalco. Before occupying Mexico City he was named by Iturbide to the Governmental Junta and after the Regency Field Marshall and captain general of the internal provinces of the West and the East when the territory of the First Mexican Empire was divided into five military districts.[2]

At Huchi he defeated the Ordenes Regiment, a Spanish expeditionary force for which he was recommended to be a part of the Regency. At the capital he was in charge of urgent matters related to the internal provinces of the country.[2]

First Republic

After the First Mexican Empire fell he joined Luis de Quintanar at Guadalajara in proclaiming a revolution in favor of the federal system, hoping that in the resulting upheaval Iturbide could find a way back to power. However the uprising was defeated and Bustamante and Quintanar surrendered before General Nicolas Bravo and the pair were banished to South America, a punishment which was never carried out due to the political upheavals afflicting Mexico at the time.[2]

During the early years of the First Republic as politics in Mexico became a struggle between the liberal, federalist Yorkino party and the conservative, centralist Escoses party Bustamante sided with the former due to being offput by the hatred for Iturbide found in the Escoses party. President Victoria gave Bustamante command of the internal provinces, and he began his duties with the rank of Division General. He set out to suppress raids and protect the frontier.[2]

First Presidency

| First Presidency of Anastacio Bustamante[3] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| Foreign and Interior Relations | Manuel Ortiz de la Torre | 1 Jan 1830 – 11 Jan 1830 |

| Lucas Alamán | 12 Jan 1830 – 20 May 1832 | |

| José María Ortiz-Monasterio | 21 May 1832 – 14 August 1832 | |

| Justice and Ecclesiastical Affairs | Joaquín de Iturbide | 1 Jan 1830 – 7 Jan 1830 |

| José Ignacio Espinosa | 8 Jan 1830 – 17 Aug 1830 | |

| Joaquín de Iturbide | 18 May 1832 – 14 Aug 1832 | |

| Treasury | Ildefonso Maniau | 1 Jan 1830 – 7 Jan 1830 |

| Rafael Mangino | 8 Jan 1830 – 14 Aug 1832 | |

| War and Marine | Francisco Moctezuma | 1 Jan 1830 – 13 Jan 1830 |

| José Antonio Facio | 14 Jan 1830 – 19 Jan 1830 | |

| José Cacho | 20 Jan 1832 – 14 Aug 1832 | |

Overthrow of Guerrero

In the elections of 1828, Bustamante was chosen to be vice-president under the Yorkino Vicente Guerrero, and he was placed in charge of the reserve forces of Xalapa. President Guerrero had been granted emergency powers in 1829 due to a Spanish Invasion, and did not resign them, which became a point of contention among the opposition. A conspiracy began to brew against the president and it succeeded in gaining the adherence of Bustamante. He was influenced by Jose Antonio Facio, a great opponent of Guerrero, and some Yorkinos disillusioned with the president.[4] On December 4, 1829, Bustamante proclaimed the Plan of Jalapa against the government on the pretext of restoring constitutional order against the president's alleged dictatorial tendencies. Guerrero gathered troops and left the capital to face the rebels, only for the insurrection to flare up in the capital itself, and the government surrendered on December 22 while Guerrero escaped to the south of the country.

Bustamante appoints a new government

.png.webp)

Bustamante officially began his presidency on January 1, 1830. He named Lucas Alamán: Minister of Interior and Exterior Relations, Rafael Mangino: Minister of Finance, Colonel Jose Antonio Facio: Minister of War and Marine, and Minister of Justice: José Ignacio Espinosa. Congress ratified the Plan of Jalapa, but it did not annul the results of the election of 1828. It rather declared Guerrero unfit to rule, and as a consequence vice-president Bustamante was now president.[5]

The new government, notably Alaman and Facio regretted the expulsion of the Spaniards which had been carried out under previous administrations, but did not attempt to undue such measures due to popular anti-Spanish feeling.[6]

Uprisings against Bustamante

Meanwhile, Guerrero remained at large in the south of the country, and the commanders who had previously all fought the Spaniards now found themselves on opposing sides of a civil conflict. On the side of Guerrero were Juan Álvarez, Francisco Mongoy, Gordiano Guzmán, and Isidoro Montes de Oca. On the side of Bustamante were Nicolas Bravo, Manuel de Mier y Terán, and Melchor Múzquiz. The conflict flared up in other parts of the country but was suppressed. A brother of the ex-president Guadalupe Victoria was executed for taking arms against the government.[7]

The problem of Texas

On April 6, 1830, the government took action against the crisis that was developing in the state of Coahuila y Tejas. The region had been increasingly settled by American immigrants since the last days of Spanish rule, and the amount of settlers now threatened Mexico's ability to administer the region. Minister Alaman passed a law prohibiting further colonization of Texas by foreigners from countries contiguous to Mexico, and enforcing customs along the frontier. General Teran was ordered to establish a string of forts along the Texas frontier. The colonists who up until this point had been living in virtual independence, to the point of openly owning slaves, which was illegal in Mexico, found the law highly irritating.[8]

Guerrero captured and executed

For the first time in Mexican history, official independence day celebrations also occurred on September 27 in addition to September 16 in order to commemorate the entrance of Agustín de Iturbide's Trigarantine Army into Mexico City in addition to the usual commemorations of the Grito de Dolores.[8] On January 1, 1831, General Nicolas Bravo struck a decisive blow against the remaining forces of Vicente Guerrero. The latter attempted to flee aboard the ship Colombo departing from the port of Acapulco, but Captain Picaluga instead docked at Huatulco and turned Guerrero over to the authorities. Guerrero was court martialed and condemned to death, being executed by firing squad on February 14. The execution of one of the heroes of independence, reminiscent of Agustín de Iturbide's death only seven years earlier, shocked the nation and rumors that the government had paid Picaluga were widespread.[9]

After the end of Guerrero's struggle in the south there was relative peace throughout the nation. Taxes and customs were increasing, and the nation's credit began to improve.[10] At the opening of congress on January 1, 1832, Bustamante reported that the states all now had considerable surplus funds, and that the treasury had enough funds to pay six months interest on the foreign debt.[11]

Beneath the increasing prosperity however lay unease over the governments increasingly autocratic measures. Freedom of speech was abolished,[12] and the legislature and judiciary grew increasingly subservient to the executive.[13]

Plan of Veracruz

On January 2, 1832, the garrison at Vera Cruz pronounced against the government, accusing the ministers of acting autocratically and demanding their dismissal. Santa Anna at this point had a reputation for being liberal, he had proclaimed for a republic when Emperor Agustín de Iturbide's was becoming increasingly autocratic, and had been a supporter of Vicente Guerrero. The opposition had gathered around him hoping that he would lead a movement to overthrow Bustamante. Santa Anna agreed to join the movement and on January 4, he addressed himself to President Bustamante offering to mediate between the rebels and the president in order to prevent bloodshed.[14]

The government failed to defeat Santa Anna, and the revolution spread to Tamaulipas, where the rebels routed the forces of Manuel de Mier y Terán at Tampico. Mier y Terán would commit suicide in the aftermath. Now the revolution was joined by more states, who now began to demand not only the dismissal of the ministers but the replacement of Bustamante himself with Manuel Gomez Pedraza who had won the elections of 1828 before fleeing the country in the aftermath of Vicente Guerrero's revolt against him. Meanwhile, the states of San Luis Potosí, Michoacán, Chihuahua, Mexico, Puebla, and Tabasco remained loyal to Bustamante, but the revolution continued to advance.[15]

The government was shaken by the news that the hereunto loyal city of San Luis Potosí was captured by the General José Esteban Moctezuma on August 6, and President Bustamante assumed personal command of the troops in order to lead an expedition against him. Bustamante stepped down as president and the deputies elected General Melchor Muzquiz to assume the role of interim president on August 14.[16]

Bustamante routed the forces of Moctezuma on September 18, and occupied the city on September 30.[17] Unfortunately for the government General Gabriel Valencia then proclaimed his support for the revolution in the state of Mexico, putting him in a position to threaten the capital. Bustamante advanced back towards Mexico City and reached Peñón Blanco where he obtained a promise from Governor Garcia of supporting the government, a promise which was later broken. Meanwhile, in Veracruz after a six-month stalemate, Santa Anna succeeded in defeating the government forces led by José Antonio Facio, allowing his army to leave Veracruz and advance upon the capital reaching Tacubaya on October 6.[18]

However Santa Anna turned back on November 6 to face the approaching army of Bustamante at the city of Puebla, where he eventually defeated him on November 16. At this point, the government had effectively lost control over the rest of the nation, retaining the loyalty of only Oaxaca and Chihuahua. Bustamante gave up the military struggle and opened negotiations at which it was agreed to enter into an armistice until congress could approve a peace treaty between parties. Congress refused to surrender, but Bustamante disobeyed them to avert further bloodshed and proceeded to negotiate a peace that was ratified on December 23, 1832, through the Treaty of Zavaleta. In accordance with the treaty, the presidency now passed on to Manuel Gomez Pedraza.[19] Bustamante was banished to Europe two years later in 1833.[20]

Life in Europe

Bustamante spend his exile travelling the nations of Europe, touring military establishments, and while in Paris, attending lectures at the Atheneum, including those of the Astronomer François Arago. In keeping with his background as a physician, he visited the anatomical collections of Montpellier and of Vienna. He learned to speak fluent French albeit with a heavy accent, and his standing as the former president of Mexico gave him access to prominent individuals.[21]

In 1833, the liberal government of Valentín Gómez Farías, which had succeeded Bustamante was overthrown by Santa Anna who had now switched sides to the conservatives and helped rewrite the constitution, establishing the Centralist Republic of Mexico, which stripped the provinces of their autonomy in favor of a strong central government. Revolts against the new constitution flared up all over the nation, and Santa Anna set out to suppress them. With the conservatives in power, Bustamante was no longer prohibited from returning to the nation. He remained in Europe for the time being, but he was heavily affected by news of the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836, through which Mexico lost Texas. The government invited him back into the country, and the newly arrived Bustamante offered his services to the nation in the war against Texas.[22]

Second presidency

With the fall of Santa Anna however, Bustamante was now the most high-profile conservative in the nation, and after the disastrous presidency of Jose Justo Corro, which had been unable to prevent the loss of Texas, congress voted to offer Bustamante the presidency which he accepted on April 12, 1837. He accepted, and published a proclamation explaining that he had left his peaceful retirement in Europe to offer his services to the nation in their struggle against the rebellious province of Texas. He lamented that there was a lack of funds to pursue this end, and promised to pursue impartial justice, and the good of the country.[23]

He chose Joaquin Lebrija as the minister of the treasury, José Mariano Michelena as minister of war, Manuel de la Peña y Peña as minister of the interior and Luis Gonzaga Cuevas, known to be an associate of Bustamante's previous minister Lucas Alamán, as minister of relations.[23]

Shortly after the inauguration, news arrived that the Spanish government had recognized Mexican independence, in a treaty concluded at Madrid with the Mexican plenipotentiary, Miguel Santa Maria on December 28, 1836. The treaty was ratified by the Mexican congress on May, 1837.[24]

Minor revolts against the government broke out at San Luis Potosí, but were suppressed. Esteban Moctezuma who had played a key role in Bustamante's first overthrow, was killed during the government's reprisals.[25]

Pastry War

Months of blockade and the military occupation of the Port of Veracruz would now follow stemming from French financial claims. France had long been attempting to negotiate settlements of damages experienced by its citizens during Mexican conflicts. The claims of a French baker based in Mexico City would end up giving the subsequent conflict its name.

Diplomatic talks over the matter broke down on January, 1838, and French warships arrived in Veracruz on March. A French ultimatum was rejected and France declared that it would now blockade the Mexican ports. Another round of negotiations broke down and the French began to bombard Veracruz on November 27. The Fortress of San Juan de Ulúa could not withstand the French artillery and surrendered the following day, and the Mexican government responded by declaring war. Santa Anna, who had been disgraced after recognizing Texan independence, emerged from his private life at Manga de Clavo to lead troops against the French, being given a command by the Mexican government.

On December 5, three French divisions were sent to land at Veracruz to capture the forts of Santiago, Concepcion, and to arrest Santa Anna. The forts were captured, but the division tasked with finding Santa Anna was fought off at the barracks of La Merced. Santa Anna lost a leg in the fighting which gained him much public sympathy after the disgrace he suffered for losing in Texas. Nonetheless the French had effective control of Veracruz and the results of the war so far led to Bustamante’s cabinet to resign. [26]

Great Britain which also had interests in Mexico had been feeling the effects of the French blockade, and had anchored thirteen vessels in Veracruz as a show of force. France, who did not wish either to enter a conflict with England or to further invade Mexico once again entered into negotiations. An agreement was reached in April, 1838 which resulted in a French departure and a Mexican agreement to pay damages to France [27]

Tampico revolt

In October 1838, another rebellion against the government broke out at Tampico, which soon placed itself under the command of General José de Urrea. The revolt spread into San Luis Potosí and Nuevo León, and the government sent Valentin Canalizo with troops that had been raised for the Pastry War. Canalizo was repulsed but not before killing the original instigator of the revolt Montenegro.[28] Government reinforcements were sent under Garay and Lemus only to switch sides and join in the rebel siege of Matamoros. The rebels now succeeded in overthrowing the governors of Monterey and Nuevo León and in March, 1839 government reinforcements under General Cos were routed by Mejia.[29]

Bustamante stepped down from the presidency and assumed command of the armed forces himself and marched to San Luis Potosí. The presidency in the meantime was held by Santa Anna. The rebels under Urrea and Mejia now made an incursion into Puebla, and Santa Anna headed out from the capital to meet them. Government forces under General Valencia defeated the rebels at the Battle of Acajete on May 3, 1839, and captured General Mejia who was summarily executed. Urrea however escaped and retreated into Tampico which fell to government forces on June 11 with Urrea being exiled.[30]

The remainder of the rebels were concentrated in the northeast, received aid from Texas, and plotted to separate the northern Mexican provinces into an independent republic. The rebels however, now experienced a series of defeats at the hands of Mariano Arista before finally surrendering to the government on November 1, 1839[31]

Third presidency

| Third Presidency of Anastasio Bustamante[32] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| Relations | Manuel Eduardo de Gorostiza | 19 Jul 1839 – 26 Jul 1839 |

| Juan de Dios Cañedo | 27 Jul 1839 – 5 Oct 1840 | |

| Jose Maria Monasterio | 6 Oct 1840 – 20 May 1841 | |

| Sebastian Camacho | 21 May 1841 – 22 Sep 1841 | |

| Interior | Jose Antonio Romero | 19 Jul 1839 – 26 Jul 1839 |

| Luis Gonzaga Cuevas | 27 Jul 1839 – 12 Jan 1840 | |

| Juan de Dios Cañedo | 12 Jan 1840 – 9 Feb 1840 | |

| Luis Gonzaga Cuevas | 10 Feb 1840 – 3 Aug 1840 | |

| Juan de Dios Cañedo | 4 Aug 1840 – 14 Sep 1840 | |

| José Mariano Marín | 15 Aug 1840 – 6 Dec 1840 | |

| José María Jimenez | 7 Dec 1840 – 22 Sep 1841 | |

| Treasury | Francisco María Lombardo | 19 Jul 1839 – 26 Jul 1839 |

| Francisco Javier Echeverría | 27 Jul 1839 – 23 Mar 1841 | |

| Manuel Maria Canseco | 24 Mar 1841 – 22 Sep 1841 | |

| José María Tornel | 19 Jul 1839 – 27 Jul 1839 | |

| Joaquín Velázquez de León | 28 Jul 1839 – 8 Aug 1839 | |

| War | Juan Almonte | 9 Aug 1839 – 22 Sep 1841 |

Bustamante returned to the capital on July 19, 1839, and faced criticism for his campaign which upon reaching San Luis Potosí had largely remained idle, and Bustamante defended his conduct by reminding his opponents about how he had directed the final and decisive campaigns of Arista.[33]

Loss of Yucatán

Bustamante would now go on to face the most serious separatist crisis the country had experienced since the Texas Revolution. Years of irritation at excise taxes, levies, conscription, and increase of custom duties culminated in Iman raising the standard of revolt at Tizimin on May, 1839. Valladolid was captured in February, 1840 and joined by Mérida. The entire north-east of the Yucatán Peninsula declared itself independent until Mexico should restore the federal system. Campeche was captured on June 6, and now the entire peninsula was in the hands of the rebels, who proceeded to elect a legislature and form an alliance with Texas.[34]

Federalist Revolt of 1840

Bustamante was not able to suppress the Yucatán movement and its success inspired the federalists to renew their struggle. General Urrea had been arrested but continued to conspire with his associates and on July 15, 1840, he was broken out of prison. With a group of select men, Urrea broke into the National Palace, snuck past sleeping palace guards, overpowered Bustamante's private bodyguard, and surprised the president in his bedchambers. As Bustamante reached for his sword, Urrea announced his presence, to which the president replied with an insult. The soldiers aimed their muskets at Bustamante, but were restrained by their officer who reminded them that Bustamante had once been Iturbide's second in command. The president was assured that his person would be respected, but was now a prisoner of the rebels. Almonte, the minister of war had meanwhile escaped to organize a rescue.[34]

Valentín Gómez Farías, the former liberal president whose overthrow in 1833 had led to the end of the First Republic, and the creation of the Centralist Republic had now arrived in the country to take command of the revolt. Government and federalist forces now converged at the capital. Federalists occupied the entire vicinity of the National Palace while government forces prepared their positions for an attack. Skirmishes broke out the entire afternoon, sometimes involving artillery. A cannonball crashed through the dining room where the captive president was having dinner, covering his table with debris. Shortly afterwards the officer charged with watching over him was hit by another cannonball. This was the same officer who had earlier restrained the rebels from shooting Bustamante, and the president, with his background as a physician tended to his wounds.[35]

The conflict appeared to be reaching a stalemate, and the president was released in order to try and reach a negotiation. Negotiations broke down and the capital had to face twelve days of warfare, which resulted in property damage, civilian loss of life, and a large exodus of refugees out of the city.[36] Now news was received that government reinforcements were on the way under the command of Santa Anna. Rather than face a protracted conflict that would destroy the capital, negotiations were started again and an agreement was reached whereby there would be a ceasefire, and the rebels would be granted amnesty.[37]

The revolt among other national disorders inspired José María Gutiérrez Estrada in October to publish an essay addressed to President Bustamante advocating the establishment of a Mexican monarchy with a European prince as the remedy for the nation's ills, his indignity over witnessing the National Palace being besieged forming a notable theme throughout the essay. President Bustamante was not sympathetic to calls for importing a foreign monarch. The resulting outrage to Estrada's monarchist plan, from both the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party was so severe that the publisher of the pamphlet was arrested, and Estrada went into hiding, subsequently fleeing the country. [38]

Bustamante's final overthrow

After the Gomez Farias revolt, the government still had to face a seemingly insurmountable series of challenges. Tabasco was now trying to secede, the north was facing Indian raids, and a nascent Texas navy was now on the offensive against Mexico. The ever-present financial crisis had also obliged the government to raise taxes.[39]

At the end of 1839, the tax on custom house duties was increased by fifteen percent, which offered little relief for the budget since most custom house receipts already went to cover debt. The budget of 1841 at the end of Bustamante's rule estimated the revenue at $12,874, 100, less $4,800,000 coming from customs, and the expenditures at $21,836,781, whereof $17,116,878, more than eighty percent went to the military, leaving a deficit of $13,762,681.[40]

The increase on customs resulted in formal protests from Mexican businessmen at the capital and at Jalisco, and the commandant general of the latter, Mariano Paredes joined the protestors and formally presented their grievances to the governor. Governor Mariano Escobedo, decreed to lower taxes and imports within his own state, but the national congress nullified most of his relief measures.[40]

Congress was pressed with a public desire for constitutional reform, but legislature stalled in the session from January to June 1841.[41]

In response to the national crises, Mariano Paredes on August 8, 1841, published a manifesto to his fellow commander generals, calling for the creation of a new government. He gathered as many troops as he could, gathered more on the way and entered the city of Tacubaya where he was joined by Santa Anna. In September, Bustamante resigned the presidency once again to lead the troops personally and left the presidency to the finance minister Javier Echeverria. He attempted to proclaim support for the federal system in order to divide his enemies, but the ploy failed. The insurgents were triumphant and Bustamante officially surrendered power through the Estanzuela Accords on October 6, 1841. A military junta was formed which wrote the Bases of Tacubaya, a plan which swept away the entire structure of government, except the judiciary, and also called for elections for a new constituent congress meant to write a new constitution. Santa Anna then placed himself at the head of a provisional government.[42]

Later years

As he did after his first overthrow, Bustamante went to Europe. When Santa Anna fell from power in 1844, he once again returned to offer his services to the nation in its increasing tensions with the United States.[43]

Under president Paredes, Bustamante was made a senator for the national constitutional assembly that was to mee in June, 1846. Bustamante was wary of changing the constitution, but when the assembly met he was made president of the congress.[43]

While offering his services, he did not see major action during the Mexican–American War. He was sent on an expedition to reinforce California, but never made it due to budget issues, and a diversion to control an uprising in Mazatlán. After the cease-fire, he was assigned to suppress another revolt carried out by Paredes, and he succeeded, pacifying Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, and the Sierra Gorda. This series of victories would be the last campaign of Bustamante's long military career.[43] He was amongst those opposed to the Treaty of Guadalupe which lost the nation half of its territory, but as the final ratification was approaching and Manuel de la Peña y Peña asked him on the wisdom of continuing the war, Bustamante merely replied that he would obey the government regardless of what it decided upon.[43]

After the war Bustamante retired from politics and made his residence at San Miguel de Allende. He spent his time talking with his friends and recounting his eventful political career or whatever had grabbed his attention during his trips. He died on February 6, 1853, at the age of seventy-two. He was buried at the Parish of San Miguel de Allende. His heart was buried next to the remains of Iturbide at the National Cathedral.[44]

See also

References

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 149.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 150.

- Memoria de hacienda y credito publico. Mexico City: Mexican Government. 1870. p. 1030.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 88.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 198.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 199.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 199.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 201.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. p. 202.

- Arrangoiz, Francisco de Paula (1872). Mexico Desde 1808 Hasta 1867 Tomo II (in Spanish). Perez Dubrull. pp. 202–203.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 106.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 103.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 104.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 107.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 114.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 115.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 118.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 119.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 123.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 159.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 204.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 206.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 207.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 181.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1879). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 182.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1885). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 198–200.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1885). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 202–204.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 209.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. pp. 209–210.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. pp. 209–212.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. pp. 214–215.

- Memoria de hacienda y credito publico. Mexico City: Mexican Government. 1870. p. 1036.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 216.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. pp. 218–219.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 221.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 222.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 223.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1885). History of Mexico volume V: 1824-1861. pp. 224–225.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 226.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 227.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe (1881). History of Mexico. Vol. V: 1824–1861. p. 228.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II. J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 287.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 236.

- Rivera Cambas, Manuel (1873). Los Gobernantes de Mexico: Tomo II (in Spanish). J.M. Aguilar Cruz. p. 237.

Sources

- Andrews, Catherine. "The Political and Military Career of General Anastasio Bustamante, 1780–1853", PhD diss., University of Saint Andrews, UK, 2001 OCLC 230722857.

- (in Spanish) "Bustamante, Anastasio", Enciclopedia de México, vol. 2. Mexico City, 1996, ISBN 1-56409-016-7.

- (in Spanish) García Puron, Manuel, México y sus gobernantes, v. 2. Mexico City: Joaquín Porrua, 1984.

- (in Spanish) Orozco Linares, Fernando, Gobernantes de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial, 1985, ISBN 968-38-0260-5.

- Macías-González, Víctor M. "Masculine friendships, sentiment, and homoerotics in nineteenth-century Mexico: the correspondence of Jose Maria Calderon y Tapia, 1820s–1850s". Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 16, 3 (September 2007): 416–35. doi:10.1353/sex.2007.0068