Felician Záh

Felician (III) from the kindred Záh (also incorrectly Zách, Hungarian: Záh nembeli (III.) Felicián; killed 17 April 1330) was a Hungarian nobleman and soldier in the first half of the 14th century, who unsuccessfully attempted to assassinate Charles I of Hungary and the entire royal family in Visegrád.

Felician (III) Záh | |

|---|---|

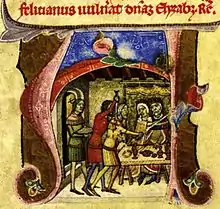

The attempt of Felician Záh on the royal family, depicted in the near-contemporaneous Illuminated Chronicle | |

| Born | 1260s |

| Died | 17 April 1330 Visegrád, Hungary |

| Noble family | gens Záh |

| Issue | Felician IV Sebe Clara |

| Father | Záh II |

Ancestry and family

Felician III originated from the gens (clan) Záh, which possessed several landholdings and villages in Nógrád County. According to historian György Györffy, the ancestor of the kindred was a leader of those Székely militiamen, who were settled for the purpose of border surveillance during the reign of Stephen I of Hungary. By the end of the 12th century, the kindred divided into several branches; due to incomplete data, there are only fragmented genealogical tables, and there is inability to connect the branches with each other. Felician's branch owned lands in the northern part of Nógrád County, at the border of Kishont County.[1]

Felician was born in the second half of the 1260s as one of the two sons of Záh II. His uncle was the influential prelate Job I, who served as Bishop of Pécs from 1252 until his death in 1280 or 1281. As a partisan of Duke Stephen, he reached the zenith of his influence in the period starting with the death of Béla IV, when he also held temporal offices in addition to his bishopric. Felician and his brother Job II were first mentioned – albeit without names – by a contemporary document in June 1272, when their father was already deceased. Both of them were still minors during the issue of the charter. Job II died sometime after 1275, leaving Felician as the sole heir of the property and wealth of his branch. Following Bishop Job's death, Felician inherited his acquired lands, but it is possible he was still minor during that time.[2] Felician also had a sister, who married Paul Balog from the Tombold branch.[3] Felician disappears from the sources for the next two decades. At sometime he married an unidentified noblewoman. They had three children, his namesake son and heir Felician IV, and two daughters, Sebe, who married local county noble Kopaj Palásti, and Clara.[4]

Military and court career

[...] This Felicianus had been raised to a high position by the former Count Palatine Matheus of Trinchinium; then he had left Matheus and come to the King. The King had shown him royal favour and love, and his door was always open to him to enter when he wished. [...]

Felician next appears in contemporary records on 18 May 1301, shortly after the extinction of the Árpád dynasty, when acted as an arbitrator during a legal process, when the borders of Pöstyén (today part of Szécsény) in Nógrád County were determined and designated.[2] The death of Andrew III resulted a civil war between various claimants to the throne—Charles of Anjou, Wenceslaus of Bohemia, and Otto of Bavaria—, which lasted for seven years. Hungary had actually disintegrated into about a dozen independent provinces, each ruled by a powerful lord, or oligarch. Among them was Matthew Csák, who dominated the northwestern parts of Hungary. He extended his influence over Nógrád County sometimes in the period between 1302 and 1308. Becoming the familiaris and confidant of Matthew Csák by then, Felician attended in a meeting in the Pauline Monastery of Kékes on the side of his lord on 10 November 1308, where the papal legate, Cardinal Gentile Portino da Montefiore managed to persuade Matthew to accept King Charles' rule. Three of the five noblemen, who escorted the oligarch, were landowners in Nógrád County, including Felician Záh and Simon Kacsics.[6]

The reconciliation between Charles I and Matthew Csák proved to be short-lived, as the oligarch did not want to accept the king's rule; therefore, he did not attend King Charles' third coronation, when he was crowned with the Holy Crown on 27 August 1310. Moreover, Matthew Csák still continued to expand the borders of his domains and occupied several castles in the northern part of the kingdom. In the same time, Felician raided and pillaged the village of Baj in Pilis County, which then belonged to the property of the Diocese of Veszprém, according to a charter dated October 1310.[7] It is possible that he is also identical with that "Fulcyanus", who devastated the church estate of Vágszerdahely (present-day Dolná Streda, Slovakia), leading a Csák military force at the turn of 1311–1312.[8] Charles I attempted to weaken the unity among Matthew's partisans through diplomatic means in the following years. According to a royal charter issued in September 1315, the king deprived three of the oligarch's servants of all their possessions and gave those to Palatine Dominic Rátót, because they absolutely supported Matthew Csák's all efforts and did not ask for the king's grace. One of these sanctioned nobles was Felician, who remained a partisan of Matthew Csák even after an internal war between his familiares over the ownership of Jókő Castle (today Dobrá Voda, Slovakia) in 1316.[9]

After Csák's military defeats throughout in 1317, numerous faithful noblemen and soldiers left his dominion and allegiance to join the royal camp. Around 1318, Felician also became a partisan of Charles I, who forgave his former infidelity, thus he managed to retain his possessions in Nógrád County.[7] He elevated into a confidential status in the royal court, while his youngest daughter Clara was made maid of honour of Queen Elizabeth.[10] Matthew Csák died on 18 March 1321, his province collapsed shortly thereafter, because most of his former castellans yielded without resistance.[11] Charles I donated the fort of Cseklész to Abraham the Red for Sempte (present-day Bernolákovo and Šintava in Slovakia, respectively) in 1323, which thus became a royal castle. Felician was made castellan of Sempte around 14 March 1326, that is the only piece of information, when he was mentioned in this capacity. In September 1328, already Lawrence the Tót (father of Palatine Nicholas Kont) and his brother Ugrin held the position.[12] Additionally, Felician was not referred as castellan already in June 1327, when one of his servants Pető was involved in a murder case. Historian Krisztina Tóth argued Felician was replaced as castellan of Sempte, because the tensions between Charles and Frederick the Fair, Duke of Austria emerged during that time, which resulted the growing importance of Sempte, thus the king assured that an old ally, Lawrence would supervise the royal castle. In the summer of 1328 Hungarian and Bohemian troops jointly invaded Austria and routed the Austrian army on the banks of the Leitha River. When Charles signed a peace treaty with the three dukes of Austria on 21 September 1328, Lawrence was also present, demonstrating his local importance.[13]

After his replacement, Felician moved to his lands in Gömör County. He resided in his estate of Gice (today Hucín, Slovakia) in December 1327. His neighbor and old nemesis Ladislaus Ákos filed a lawsuit against Felician and his namesake son, but they were not present at local county court. Later land donations confirm that Charles I ruled in favor of Felician in the upcoming lawsuits against Ladislaus, thus he did not fall out of the king's favor, but certainly lost political influence.[13] In January 1329, Felician complained that one of his familiares, French, son of Benedict left his service and stole 100 marks. He decided to punish the insult: on 19 February, his soldiers invaded French's house and captured his servant John and swineherd Bene. They were subsequently tortured to death. French denied the accusation of theft, and Nicholas Treutel, the ispán of Pozsony County forced the parties to duel. However, Felician and French finally agreed with each other. Felician summoned 30 nobles, who justified his accusations: subsequently, French had to pay 60 marks as compensation. The document issued on 10 August also stated that if Felician dies in the meantime, his son, Felician IV owes the remaining debt, which French had to pay nineteen days later, on 29 August. This short period of time confirms Felician's advancing age and, probably, declining health.[14]

Failed regicide

Assassination attempt and death

Although in these times the people of Hungary enjoyed the loved tranquility of peace and the kingdom was on all sides secure against its enemies, yet the hater of peace and the sower of envy, the devil, put into the heart of a certain soldier named Felicianus, of the line of Zaah, who was already advanced in years and his hair silvered, that he would in one day kill with his sword his lord King Charles and Queen Elizabeth, and the King's two sons Lays and Andreas. [...] In the year of our Lord 1330, on April 17, the Wednesday [sic] after the octave of Easter, the King was at dinner with the Queen and his sons in his residence before the castle of Vyssegrad, when Felicianus secretly entered and stood before the King's table. He drew his sharp sword from its scabbard and like a mad dog threw himself upon the King, the Queen and the sons in pitiless desire to kill them. But the pity of a pitiful God prevented him from executing his intent. Yet he slightly wounded the King in the right hand. But, alas, from the right hand of the most saintly Queen he severed four fingers which in her almsgiving she was wont to extend in pity to the poor, the wretched and the downcast. [...] Then he [Felicianus] tried to kill the royal princes who were present, but their tutors, Gyula de Kenesich's son [Nicholas Tapolcsányi] and Nicolaus, son of the Count Palatine Johannes, placed themselves in his way and received mortal wounds in the head, but the boys were unhurt. Then Johannes, son of Alexander from the county of Potok, a youth of good disposition who was the Queen's second cup-bearer, threw himself upon Felicianus as upon a wild beast and struck at him with a dagger [bicellus] between the neck and the shoulder with such force that he felled him to the ground. Then from this side and that the King's soldiers rushed in and dispatched him as if he were some monster, severing the wretch's limbs with their terrible swords. [...]

On 17 April 1330, Wednesday, Felician Záh, stormed into the dining room of the royal palace at Visegrád with a sword in his hand and attacked the royal family. He wounded both Charles and the queen on their right hand and attempted to kill their two sons, Louis and Andrew, before the royal guards killed him.

Subsequent reprisal

His [Felician's] head was sent to Buda and his hands and feet to other cities. His only son, who was a young lad, and a servant who was faithful to him, took to flight, but they were caught and tied to the tails of horses, and thus they ended their life. The bodies were cast into the street, and the dogs gnawed their bones.

References

- Tóth 2014, p. 640.

- Tóth 2014, p. 643.

- Engel: Genealógia (Genus Balog 4. Tombold branch)

- Beihuber 2006, p. 110.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 206.142–143), p. 146.

- Kristó 1973, pp. 61–62.

- Beihuber 2006, p. 112.

- Kristó 1973, p. 127.

- Tóth 2014, p. 644.

- Tóth 2003b, p. 48.

- Kristó 1973, p. 201.

- Engel 1996, p. 409.

- Tóth 2014, p. 645.

- Tóth 2014, p. 646.

Sources

Primary sources

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

Secondary studies

- Almási, Tibor (2000). "Záh Felicián ítéletlevele [The Sentence Letter of Felician Záh]". Aetas (in Hungarian). AETAS Könyv- és Lapkiadó Egyesület. 15 (1–2): 191–197. ISSN 0237-7934.

- Bagi, Dániel (2021). "Záh Felicián ügye Mügelni Henrik német nyelvű krónikájában [The Affair of Felician Záh in the German Chronicle of Henry of Mügeln]". Pontes (in Hungarian). PTE BTK Történettudományi Intézet. 4: 131–143. ISSN 2631-0015.

- Beihuber, Ádám (2006). "Borcseppek a kardélen. Gondolatok Záh Felicián merényletéről [Wine Drops on the Sword Edge: Thoughts About Felician Záh's Assassination]". Sic Itur Ad Astra (in Hungarian). 18 (1–2): 109–125. ISSN 0238-4779.

- Csukovits, Enikő (2012). Az Anjouk Magyarországon. I. rész. I. Károly és uralkodása (1301‒1342) [The Angevins in Hungary, Vol. 1. Charles I and His Reign (1301‒1342)] (in Hungarian). MTA Bölcsészettudományi Kutatóközpont Történettudományi Intézet. ISBN 978-963-9627-53-6.

- Engel, Pál (1996). Magyarország világi archontológiája, 1301–1457, I. [Secular Archontology of Hungary, 1301–1457, Volume I] (in Hungarian). História, MTA Történettudományi Intézete. ISBN 963-8312-44-0.

- Gerics, József (2004). "Záh Felicián ítéletlevelének valószínű mintájáról [The Probable Pattern of Felician Záh's Sentence Letter]". In Erdei, Gyöngyi; Nagy, Balázs (eds.). Változatok a történelemre, Tanulmányok Székely György tiszteletére (Monumenta Historica Budapestinensia 14. kötet) (in Hungarian). pp. 209–211. ISBN 963-9340-41-3.

- Kristó, Gyula (1973). Csák Máté tartományúri hatalma [The Provincial Lordship of Matthew Csák] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó.

- Mátyás, Flórián (1905). "Népmondák és történeti adatok Záh Feliczián merényletéről [Folk Legends and Historical Facts on Felician Záh's Assassination]". Századok (in Hungarian). Magyar Történelmi Társulat. 39 (2): 97–118. ISSN 0039-8098.

- Tóth, Ildikó (2003a). "Egy 1331. évi adománylevél margójára (Adalékok a Záh Felicián-féle merénylet következményeihez) [To the Margin of a Deed of Gift of 1331 (Remarks to the Consequences of Felician Záh's Assassination)]". Acta Universitatis Szegediensis: Acta Historica (in Hungarian). 117: 75–83. ISSN 0324-6965.

- Tóth, Krisztina (2003b). "Hirtelen merénylet vagy szervezett összeesküvés? (Újabb adatok Zách Felicián merényletéhez) [Sudden Assassination or Organized Conspiracy? (Newer Data for Felician Zách's Assassination)]". Turul (in Hungarian). 76 (1–2): 47–51. ISSN 1216-7258.

- Tóth, Krisztina (2014). "Még egyszer Zách Felicián merényletéről [Once Again About Felician Záh's Assassination]". In Bárány, Attila; Dreska, Gábor; Szovák, Kornél (eds.). Arcana tabularii. Tanulmányok Solymosi László tiszteletére (in Hungarian). Magyar Tudományos Akadémia; Debreceni Egyetem; Eötvös Loránd Tudományegyetem Bölcsészettudományi Kara; Pázmány Péter Katolikus Egyetem. pp. 639–652. ISBN 978-963-4737-59-9.