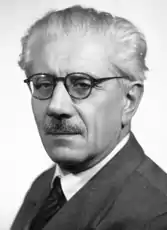

Ferruccio Parri

Ferruccio Parri (Italian pronunciation: [ferˈruttʃo ˈparri]; Pinerolo, 19 January 1890 – 8 December 1981) was an Italian partisan and anti-fascist politician who served as the 29th Prime Minister of Italy, and the first to be appointed after the end of World War II. During the war, he was also known by his nom de guerre Maurizio.

Ferruccio Parri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of Italy | |

| In office 21 June 1945 – 10 December 1945 | |

| Monarch | Victor Emmanuel III |

| Lieutenant General | The Prince of Piedmont |

| Preceded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| Succeeded by | Alcide De Gasperi |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 21 June 1945 – 10 December 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| Succeeded by | Giuseppe Romita |

| Minister of the Italian Africa | |

| In office 21 June 1945 – 10 December 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Ivanoe Bonomi |

| Succeeded by | Alcide De Gasperi |

| Member of the Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 25 June 1946 – 31 January 1948 | |

| Parliamentary group | Republican |

| Constituency | Single national constituency |

| Member of the Senate of the Republic[lower-alpha 1] | |

| In office 12 June 1958 – 8 December 1981 | |

| Parliamentary group |

|

| Constituency | Piedmont |

| In office 8 May 1948 – 24 June 1953 | |

| Parliamentary group | Republican |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 January 1890 Pinerolo, Piedmont, Italy |

| Died | 8 December 1981 (aged 91) Rome, Italy |

| Resting place | Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno, Genoa |

| Political party | PdA (1942–1946) CDR (1946) PRI (1946–1953) UP (1953–1957) Ind (1957–1981) |

| Spouse |

Ester Verrua

(m. 1922; died 1980) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Italy National Liberation Committee (1943–1945) |

| Branch/service | Royal Italian Army (World War I) Corpo Volontari della Libertà (World War II) |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | World War I

|

| Awards | |

Biography

Parri was born in Pinerolo, Piedmont. He served in World War I, when he was wounded four times and received four decorations.[1] In the final stages of the war he worked as a staff officer on the planning of the battle of Vittorio Veneto. After the war he graduated in literature and became a teacher in Milan and an editor for the Corriere della Sera.[2] He left the newspaper in 1925, after it was taken over by the Fascist government,[2] and had to quit his teaching job because he refused to join the National Fascist Party.

Resistance to Fascism

He became active against Benito Mussolini's Fascist regime and joined Carlo and Nello Rosselli's Giustizia e Libertà) ("Justice and Liberty"), the most important Italian non-Marxist anti-fascist movement.[3]

In 1926, together with Carlo Rosselli and future President of Italy Sandro Pertini he was involved in planning and assisting the escape to France of reformist Socialist leader Filippo Turati. For this he was arrested and sentenced to ten months of imprisonment[4] and then to five years of internal exile to the islands of Ustica and Lipari and to Vallo della Lucania. In 1930 he was again banished for five years together with other leaders of Giustizia e Libertà.[5]

Parri remained in contact with Giustizia e Libertà, and in 1942 founded the Action Party, an anti-fascist liberal socialist movement that sought to pair social justice and respect for civil liberties. In September 1943, after the armistice between Italy and the Allied powers and the German occupation of Italy, he was among the people indicated by anti-fascist parties to take a leading role in the Italian resistance movement. Living underground in Nazi-occupied Northern Italy, he became a member of the National Liberation Committee[6] and deputy commander of the main group of partisan forces, the Corpo Volontari della Libertà.

He was arrested in Milan in January 1945 by the Waffen SS during a routine operation. He was held prisoner until March when he was released as part of Operation Sunrise – a series of secret negotiations between Allen Dulles, head of the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and representatives of the German Wehrmacht command in Northern Italy. The release of Parri was requested by the OSS as evidence of good faith and the ability to act.[7][8] He returned in time to take part in the final phase of the resistance and in the general insurrection in April.

By the time the war ended the Giustizia e Libertà Brigades, the military arm of the Action Party, were the second largest partisan units, accounting for about 20% of all fighters of the Italian resistance movement.[9]

Prime Minister of Italy

After the end of World War II, he was appointed leader of a government supported, among the others, by the Action Party, Christian Democracy (Democrazia Cristiana; DC), the Italian Communist Party (Partito Comunista Italiano; PCI), the Italian Socialist Party (Partito Socialista Italiano; PSI) and the Italian Liberal Party (Partito Liberale Italiano; PLI). A centrist, he had been chosen as the compromise leader of a compromise Cabinet. He was also the Minister of the Interior (in charge of the police).[1] When the Liberals withdrew their support from the coalition government, Parri resigned from his position.[10]

At the time, Parri warned: "Beware of civil war ... of reopening the door to fascism. ... There are rumors that Washington and London have no trust in me. The real reason for this lack of trust is that Italy has only a fragile front of antifascism. ... I hope my successors will follow the only worthy policy for Italy: left of center".[10]

In Parliament

In spite of the wartime strength of Giustizia e libertà the Action Party quickly faded from the Italian political scene, winning 1.46% in the 1946 Constituent Assembly election. Parri, along with Ugo La Malfa, left the party shortly before the election to form the Republican Democratic Concentration (Concentrazione Democratica Repubblicana; CDR), which won 0.42% and elected its two most prominent members as deputies. The CDR would be absorbed the following year into the Italian Republican Party (PRI).

He became a Senator in 1948.

In 1953 Parri, who was opposed to recent changes to the election law, left the PRI to establish the short-lived Popular Unity (Unità Popolare; UP) with former Action Party member Piero Calamandrei, with the goal of preventing the centrist coalition from winning a majority bonus of seats. The party, which failed to elect any members, was absorbed into the Italian Socialist Party in 1957.

In 1958 he was re-elected to the Senate as an independent in the Socialist party list. He proposed to form a parliamentary inquiry committee to investigate the Sicilian Mafia. The proposal was opposed by the parliamentary majority with various arguments, and dismissed by Christian Democratic Senators Bernardo Mattarella and Giovanni Gioia as "useless".[11] It was finally established in 1963.

In 1963, President Antonio Segni appointed Parri senator for life. He joined the Independent Left group, and was for a long time its chairman from 1972 until his death. In March of the same year, he became the editor of the magazine L'Astrolabio, in which he argued in favour of a more accomplished democracy and denounced the resurgence of neofascism.[12][13]

From 1949 until 1969 he was president of the Italian Federation of Partisan Associations, an association of Resistance veterans that grouped members of Giustizia e Libertà, as well as members of Socialist, Republican, and anarchist groups.

Death

Parri died in Rome on 8 December 1981.[14]

He once characterized himself: "I am a common man – uomo della strada. I am just another guy – uomo qualunque ... I hope a typical one. My job is not only to prevent the right and left wings from exercising undue influence on the Government, but I have to think too of the enormous masses of peasants sweating in the fields under the sun, blacksmiths beating their anvils in villages, workers, men and women everywhere who have no taste for politics and are outside parties. ... I am just a uomo della strada."[1]

Notes

- Senator for life starting on 2 March 1963

References

- "Common Man", Time, 2 July 1945.

- Douglass Charles Day (1982). The Shaping of Postwar Italian Politics: Italy 1945-1948 (PhD thesis). The University of Chicago. p. 102. ISBN 979-8-205-08303-4. ProQuest 303267078.

- "Outside Party Lines", by Alexander Stille, The New York Times, 19 December 1999.

- "Biography of Sandro Pertini", Associazione Nazionale Sandro Pertini

- (in Italian) "Biography of Parri" on Antifascismo.

- Miller, James Edward (1999). "Who chopped down that cherry tree? The Italian Resistance in history and politics, 1945–1998". Journal of Modern Italian Studies. 4 (1): 37–54. doi:10.1080/13545719908454992.

- Intelligence cables covering the capitulation of the Nazi armies in northern Italy, Center for the Study of Intelligence

- "Operation Sunrise: America's OSS, Swiss Intelligence, and the German Surrender 1945", by Stephen P. Halbrook in "Operation Sunrise". Atti del convegno internazionale (Locarno, 2 maggio 2005), a cura di Marino Viganò - Dominic M. Pedrazzini (Lugano 2006), pp. 103-30.

- Le formazioni GL nella resistenza. Documenti (in Italian). Milan: Franco Angeli. 1985. p. 395.

- "Split", Time, 3 December 1945.

- (in Italian) L'istituzione della prima Commissione parlamentare d'inchiesta sulla mafia in: L'art. 41-bis l. 354/75 come strumento di lotta contro la mafia, by Elisa Fontanelli, bachelor's degree dissertation, Florence University, 2005

- (in Italian) Ferruccio Parri, Centro Studi Politici e Sociali F. M. Malfatti (accessed 30 January 2011)

- Roland Sarti Italy: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present, Infobase Publishing, 2004, p.532

- "E' morto Ferruccio Parri" (PDF). l'Unità. 9 December 1981. p. 1. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

Bibliography

- (in Italian) Carlo Piola Caselli, Il taccuino di Ferruccio Parri sull'Europa (1948-1954), 2012

External links

- (in Italian) Biography on Antifascismo

- (in Italian) Biography

.svg.png.webp)