Field hockey stick

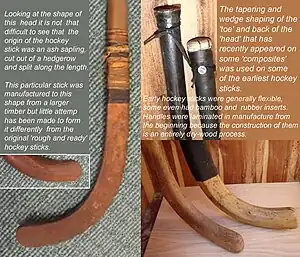

In field hockey, each player carries a stick and cannot take part in the game without it. The stick for an adult is usually in the range 89–95 cm (35–38 in) long. A maximum length of 105 cm (41.3") was stipulated from 2015.[1] The maximum permitted weight is 737 grams.[2] The majority of players use a stick in the range 19 oz to 22 oz (538 g - 623 g). Traditionally hockey sticks were made of hickory, ash or mulberry wood with the head of the sticks being hand carved and therefore required skilled craftsmen to produce. Sticks made of wood continue to be made but the higher grade sticks are now manufactured from composite materials which were first permitted after 1992. These sticks usually contain a combination of fibreglass, aramid fiber and carbon fibre in varying proportions according to the characteristics (flexibility; stiffness; resistance to impact and abrasion) required.

Early rules

After centuries of different variations of field hockey (including a version in England, sometime prior to 1860, in which, because of the very hilly heathland area in which it was played, a rubber cube and not a ball was used), the game became more organised and regularised.

By 1886, when an association of clubs was formed and the game became more standardised, the modern game as we know it began (and a white painted cricket ball had become the standard object to play with). The game had also by this time divided into various branches which developed as separate sports. Shinty, a game popular in Scotland, uses both sides of a round stick with a curved end, which is shaped in a similar way to a walking stick; the Irish game, hurling, uses both sides of a stick which is flat on both sides and shaped somewhat like bill-hook with an axe-like handle. Bandy also uses both sides of the stick. It was called "hockey on ice" in the beginning, as it was considered an ice variety of hockey. The stick in England, possibly because of the close association with it of cricket players, developed with a stick with just one flat playing side, the left face, below a round grip area—with the use of the right-face side, which is rounded, prohibited—an oddity that had a profound effect on the later development of the hockey stick and of the game itself.

There have been only three parts of a hockey stick ever named in the rules: the head, the handle, and the splice. Originally (until 2004) the handle was the part above the bottom end of the splice and the head was the part below the bottom end of the splice. Other terms in common use are "grip", which refers to the part of the stick held, particularly that area held with two hands when hitting the ball. Most sticks have a round grip which is covered in a non-slip, sweat absorbent, fabric tape. The handle remains rounded on the reverse, back or right hand-side but becomes gradually flat on the "face" side and also becomes wider, changing from a diameter of approximately 30 mm to a flat width of approximately 46 mm (the permitted maximum was 2 in—now 51 mm). This flat area above the curve of the head is generally referred to as the "shaft". The head of the stick is generally thought of as the curved part. The right side is called the face, the upturn the "toe" and the bend of the head where it joins the shaft the "heel". In recent times using the edges of the stick (as well as the face side) to strike at the ball has been permitted and thus "forehand edge stroke" and "reverse edge stroke" will be found in rule terminology. Forehand and reverse stroke refers to the taking of these strokes, from the right or left hand side of the body respectively, as the stick may be used "face up" or "face down" to make an edge stroke, the two edges of the stick are not separately named but simply referred to as edges.

Initially there were six rule requirements applying to the hockey stick:

- The stick had to be flat on the playing side (the left side when the toe of the stick head is facing away from the user).

- It had to be able to be passed completely through a two-inch (internal diameter) ring.

- The stick was to be smooth (no rough or sharp edges).

- The head of the stick was to be a) curved and b) made from wood.

- A maximum and minimum weight were specified, 28 oz and 12 oz respectively.

During the 19th century, field hockey evolved in England. This evolution led to the creation of the Federation Internationale de Hockey (FIH) in 1924.

Contance Applebee is responsible for introducing field hockey to the United States in 1901. The United States Field Hockey Association was formed in 1922.

In 1908, men's field hockey was introduced into the Olympic Games. Women's field hockey was first recognized in the Olympic Games in 1980.

The World Cup is the crowning achievement in international field hockey. The World Cup is held every four years and 12 men's and 12 women's teams compete for the title of World Champion.

Head length

The first major developments to what was later termed the "English style" stick (and the method of play with such sticks) occurred in India. (The game in its modern form was apparently brought to India by the British Army, although there does not appear to be any specific evidence of this. But certainly hockey was played by the British forces in India.) At that time the stick head was very long (in excess of 12"—300 mm) and made from an indigenous British timber, ash. The Indians then produced sticks with a much shorter head length and a tighter heel bend and used mulberry, which is tougher than ash, but has similar bending characteristics and weight and is easy to work. This development changed the nature of the game, led to the "Indian dribble" and to Indian dominance of the game in the first half of the twentieth century.

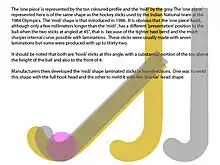

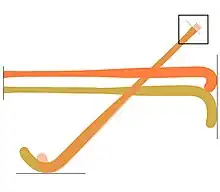

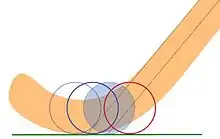

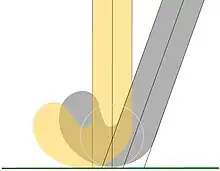

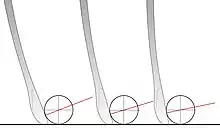

A hockey stick is occasionally used in the vertical position shown, but manipulating the movement and the direction of the ball in a controlled way (dribbling) is carried out in what is termed a "dribbling crouch", when the handle of the stick will usually be angled between 35° and 55°. Hitting or pushing the ball can be done with the stick at any angle between the vertical and horizontal and recent changes to the rules allow even the edges of the stick to be used to sweep or strike at the ball on the ground. The various stick head designs can be compared in respect of how, with the handle at an angle of 45°, they differ in the carrying out of the Indian dribble, i.e. controlling the direction of the ball by rotating the stick head over the top/front of the ball rather than (or as well as) around the back of the ball (the English style dribble). The multi-layered stick head diagram indicates the changes in head shape and length that occurred over thirty years or so.

The earliest trend was in shortening the stick head. While that reduced the stopping area of the head it was beneficial because, according to the rules at the time, only one side of the stick head could be used (at that time the ball could not be played with the edges of the head or handle but with the flat side or face side only).

Using extreme examples is useful as a means of demonstrating effects that occur in less extreme configurations but are much more difficult to spot and therefore to explain. The first observation is an easy one (top left in the image captioned "Reversed head in various…"). If the stick head is rotated onto the reverse (lighter colour) the toe is not going to disappear into the ground to enable the reverse side of the stick to be presented to the ball—a vertical adjustment is necessary. Secondly (top right), if the handle of the stick is kept at exactly the same angle and rotated, a horizontal adjustment is necessary to bring the reversed head to a position where contact will be made with the ball. The third figure (bottom left) shows these adjustments having been made (and a change to the angle of the handle because the position of the hand holding the stick at the top would be about the same as it is when gripping the stick in the forehand position), but the area of stick head making contact with the ball is very small; so control may not be adequate. The fourth figure (bottom right) demonstrates that to get good contact with the ball on a larger area of the reversed head, it is necessary to move the handle much nearer to the vertical. This means the player must bring the ball in very close to the feet and come to a more upright dribbling position—this in turn impairs the ability to scan the pitch and keep the ball in peripheral vision at the same time—a considerable disadvantage when dribbling to evade opponents.

So, although the long head stick was an adequate shape for a dribbling style which was based on moving the ball forward from directly behind the ball; and changes of direction could be achieved by rotating the stick around the back of the ball and/or moving the feet to either side of the ball, it was not so easy to use the long stick head to bring the ball across the feet and back again, particularly when it was placed wide to the left of the feet of the player. (This left side position was compounded in difficulty with a very severe interpretation of "obstruction", which prohibited shielding of the ball from an opponent. The game was also, at the time, seen as "right-sided" and positioning the body between the ball and a close or closing opponent, approaching from the right hand side, was not allowed.) Reversed stick hitting, pushing and flicking would be short range skills and difficult to do accurately, if at all, especially when moving at speed.

Gradually over many years stick heads were made shorter and the "heel" was made to a tighter bend. This process continued until the "one piece" head could not be made to a sharper bend without the timber splitting out on the base. As it was, attempts to have the grain follow entirely the same curve as the bend, as it should for maximum strength (this is why the timber is bent rather than cut to shape) were abandoned by some producers and an upturn to the toe was sometimes achieved by cutting across the wood-grain at the toe end of the head to achieve the desired shape. Some manufacturers resorted to gluing a separate piece of wood on top of the toe or glued additional strips of timber to the inner edge of the handle above the head to get the effect of a tighter heel bend. ("Head adjustment" frequently happened to update old style stock or where unmodified presses were in use.).

Some players were cutting part of the toe off their sticks, to achieve a shorter head, and rounding the end off, (although on the older styles this did nothing to tighten the bend to the heel and often just ruined the stick). Predictably, there were sticks produced for the 1986 World Cup with heads with a horizontal length of only 95 mm. The international players to whom they were handed out tried them and then returned them as unusable.

The difficulty was twofold: 1) The toe was so short that it could not be rotated completely over the top circumference of the ball and 2) When the stick head was played around the back of the ball it "ran off", because there was insufficient "run length" to the stick head. If, for example, a player "propped" the ball while moving in a dribbling crouch (putting the stick head over the front of the ball), drew the ball back towards his feet and then took the stick head around the back of the ball to bring it forward again, perhaps moving the ball off in another direction (a common movement), the margin for error was so small that the ball could easily slip off the stick head. The ultra-short stick head was to some extent based on the idea that the new artificial surfaces would lead to a style of hockey based on stopping the ball with the handle of the stick near horizontal to the ground and that dribbling to elude opponents would be almost eliminated with near continuous passing of the ball. Although there was a development of "system hockey" that overcame the stick/ball skill deficiencies of the Europeans compared with India and Pakistan at the time, it was not as fluid as the kind of one and two touch passing game common in soccer and that ideal was (and still is) a long way off.

The hook

In 1982 a Dutch inventor, Toon Coolen, patented a hockey stick with a "hook" head. The hockey stick manufacturers Grays took the design up in 1983 and the first mass-produced hockey sticks, with laminated timber head parts, were manufactured in Pakistan. This new design was possible because of the development of epoxy resin glues that did not require perfectly dry timber for bonding and curing to a strength that could cope with the immense stresses placed on a stick head when a hockey ball is struck with it.

By 1993 the "Hook" patent, had been ruled (following a court case in Germany) to protect only hook shapes within 20° of the vaguely written "nearly 180°" (referring to the degree of upturn of the toe in relation to the shaft of the stick in the patent description; the shaft of the handle being described a being bent through "nearly 180°" to form the hook shape of the stick head). That opened the way for the appearance of more J-shaped stick heads and the gradual morphing of the "midi" shape with the hook shape. In that year also a patent application, lodged in Pakistan in 1987 by Martin Conlon, for a kinked shaft hockey stick, with a set-back head (which was also hook shaped, but not to "near 180°"), was granted after strong opposition in Pakistan. (Indian and UK patents had been granted in 1988, although the same company had also opposed the UK patent application). Conlon designed and imported to the UK the first J-head sticks in 1990 but, prior to the 1993 decision, other distributors and manufacturers had been very reluctant to order made or produce hook style sticks of any sort, because of uncertainty about the strength of the patent that "ring-fenced" the hook hockey stick.

The "midi" head

The death knell of the ultra short head was sounded in 1986, due to the introduction of the midi head shape, produced with a laminating process; although of course many players continued to use "one-piece" short head sticks for many years after that date and many thousands more of them were manufactured. The reason for the continued use of the one piece was that the midi length was similar to that of the more popular one piece stick heads that had been around for the previous ten or so years. Some one piece constructions were still being produced on presses on which the central boss had not been modified and the heel bend was "slower" than on that of the production of the more aware manufacturers, but the more "go ahead" manufacturers were producing a one piece that could compete well with the laminated midi—at least as far as playing functionality was concerned.

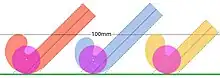

The biggest casualty of the midi was the patented Hook produced by the same company. It had not taken off in the UK culture of the short-head stick and for a number of years after the midi was introduced the Hook was seen as something of a novelty, even as an indoor stick or a stick exclusively for goalkeepers. In fact versions of it were produced specifically for goalkeepers, with a very extended toe (6 in—150 mm or more) and that development continued until some were made with the toe extending nearly the length of the handle and the FIH stepped in and ruled that the vertical toe limit was in future to be 4 in (100 mm).

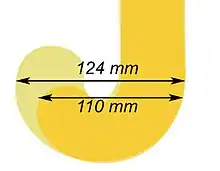

The hook was 124 mm, measured horizontally across face of the stick head, when the handle was held vertically; the midi was 113 mm; many one piece heads between 110 mm and 115 mm, and the unusable ultra short 94 mm. A difference of only 30 mm between the head length of a stick that was considered cumbersome (although the Hook also had the height of the toe causing a feeling of imbalance) to one that was considered too short to easily play with. There were still many players playing quite happily with a stick with a head length of 7 in (175 mm), but players buying new sticks were now conscious of quite subtle differences in stick feel and performance due to length, shape, and the distribution of head weight—not just the total ounce weight and the "swing weight or balance" of the stick—and for the first time, in the years after 1986, were being offered a wide range of hockey sticks from a greatly increased number of manufacturers, from which to choose what suited them. After the arrival of the laminations, some brands were offering as many as ten different shapes or styles of stick head on the traditional shaft. The arrival of composites would complicate the picture further.

In the early 1990s there were an astonishing number and variety of hockey sticks on offer compared with what had been available ten years earlier. By 1992, hockey stick reinforcement was a big issue and composites had been accepted into an (extended) FIH experimental trial period (there was a great deal of concern about the power generated by these new reinforcements and the safety of players). There were also hockey sticks with metal handles and inserted plywood heads (made by the American company Eastons, better known for making baseball bats), as well as the wide range of one piece head sticks still produced and an expanding range of laminated midi and laminated shorties. The metal handled sticks were later banned for "safety reasons", in what was widely regarded as a political move by the FIH.

Heel bend, ball position, hitting & stopping

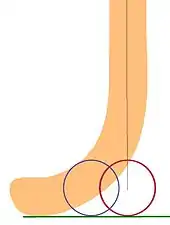

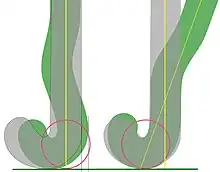

It may be noted from the diagram above that no matter how "tight" the heel bend, reversing the stick head over the ball, with a "traditional" style hockey stick head, always requires both a vertical and horizontal adjustment of the stick head position. This is not anywhere near as difficult as it was with the very long head stick and this sort of adjustment will be almost sub-conscious in an experienced player. Note too, that when the shaft is held vertically, the ball is more securely stopped, when on the ground, to the toe side of the shaft rather than in the middle of the shaft. Novice players frequently assume that the centre of the ball will align with the centre of the shaft when stopping the ball in this way and as a result, the ball deflects off to the heel side and usually into their feet. Because of the heel slope on the stick head the vertical shaft stop is actually much easier to carry out securely (when the ball is on the ground) if the handle is held at least 10° off the vertical, with the top of the handle sloped to the player's left. When the ball in the air, a little off the ground, below knee height for example, is often easier to catch the ball correctly if the handle is vertical.

One of the incidental effects of the tighter heel bend of the modern stick is an increase in playing reach with the optimum striking or stopping part of the head of the stick when used in the normal range of playing angles. Held parallel the distance between the curve of the base of the stick head and the top of the handle is the same in the two sticks illustrated. At an angle of 45°, as shown, there is a difference of approximately 3 cm.

The positioning of the ball mid-face on the stick head of the modern stick, compared with the mid-face position on the longer stick, also brings the middle of the ball much closer to a line projected through the centre of the handle and the circumference closer to the back edge of the stick, enabling better close control of the ball.

It will be appreciated after a glance at the illustration of the 'English' style hockey stick that stopping a ball on the ground with the handle held vertically would not be easy. If the ball is lined up centrally with the centre of the handle (red) it would be likely to deflect off the heel side of the head. Even with the ball positioned central to the head (blue) stopping would not have been very secure with an upright handle.

Presenting the stick at an angle of 35° or more (40° in the illustration) solves the problem of the ball running off the head by presenting a very long area behind the ball (relative to the width of the ball) but presents the problem of the best or optimum position to stop the ball for the following action. For hitting the optimum positions seems to be where a line projected through the leading edge of the shaft of the handle passes through the centre of the ball because it is the position closest to the centre line of the handle where the entire width of the head is behind the ball. Stopping the ball closer to the toe of the stick is acceptable but not optimal, as adjustment, which takes time, is necessary before the next intended action.

In the modern stick the vertical handle position is still not as secure as an angled presentation of the handle but the angle now can be considerably less, because of the tighter heel bend and the stopping and hitting positions of the ball are easier to determine. The line of the leading edge of the handle still projects close to the center of the ball when the angle of the stick handle is in the 30°–50° range and a line through the centre of the handle will project to the back and underside of the ball.

Set-back heads, ball position & stopping

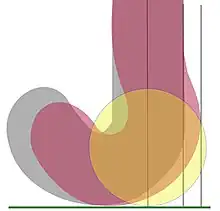

The illustration called 'Stopping and Hitting' shows that when a vertical stick shaft is aligned to the centre of the ball part of the ball protrudes to the heel side, this would happen even if the heel was not a bend but a 90° corner and the only way to cover the entire ball with the shaft held vertical is to use a set-back head—that is a head that is set-back to the heel side of the shaft.

A stick with a set-back head and toe-side protrusion, with the handle positioned vertically, covers substantially more of the ball and can reduce off heel deflection errors in stopping. Using the set-back head in the more comfortable or natural stopping angle puts a vertical area of shaft above the ball while at the same time aligning centre ball and a line projected through the centre of the handle.

In the upright hitting position, which is generally between 15° and 25° off vertical, the heel bend of the Indian stick of the 1970s will cover the whole ball. As the heel bend gets tighter in the 1980s and 1990s the ball is controlled closer to the centre line of the stick but it is not until the setback stick appears that the centre of the shaft is aligned (or nearly so) with the centre of the ball. The ball appears to move back along the length of the various stick heads as the heads become shorter and the heel tighter, in fact the playing position of the ball is moved further and further from the feet as playing reach is increased.

There are presently two styles of outfield set-back stick, the degree of setback to the head is a feature they have in common; they differ in that one has a 'kink' or shaft protrusion on the toe side above the head of the stick while the other does not. In the goalkeeper versions some also have the toe of the head cut flat (parallel to the handle) rather than rounded to allow the user to present the stick closer to the ground when stopping in a horizontal position on the reverse side, this is to more easily prevent the ball from going under the handle of the stick.

The modern hook

In the mid-90s the "hook" head style hockey stick was relaunched, this time by the former German U21 International player Thomas Kille. Bright colours, bold graphics and painted heads were introduced. Manufacturers became much more aware of the look of their products and hockey sticks sold, particularly to new players, as much on colour and fashion as strength and usability.

Today, across many brands, there is a choice of angle of hook upturn, 45°, 60°, and 75°. A style of stick that almost no-one in Europe wanted to use in 1987, is today used almost universally; it is difficult now to find a player who is not using a hook style hockey stick and many of them have never used the "shortie" style at all; just as many of the players of today have never played hockey on a natural grass pitch—the development of artificial surfaces has also had a significant effect on the ways in which hockey sticks are used.

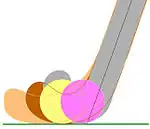

The original version, the 'Hook' relied on a patent description that put the inner side edge of the toe parallel (or nearly so) to the facing edge of the handle. The vertical height of the toe was approximately 80 mm (dotted line) Fig.1 and it was of almost uniform thickness with the remainder of the stick head.

Early modification Fig. 1. reduced the horizontal head length to approximate 115 mm and the 'toe height' to approximately 75 mm. A hockey ball is between about 71 mm and 75 mm in diameter (224–235 mm in circumference)—so that put the 'toe height' at the same height as the maximum height of the ball. This is a common feature across hook head designs today, the toe generally varies in height, between the minimum and maximum height of the ball, when the handle is in a vertical position.

The next development was a hook with a toe with an inner edge that sloped away from the handle by approximately 30° (a 60° angle to the ground or a 150° 'upturn'. The 'toe height' was 75 mm. (Modern versions Fig. 2 vary between 70 mm and 75 mm. in toe height.) The horizontal length of the head was based on the length of the 'standard' one-piece short-head stick, approximately 110 mm. and modern versions seem to vary between 110 mm and 115 mm. The mid-90s saw the introduction of the more 'open' hooks Fig. 3, some at 45° and a significant increase in horizontal head length, some as much as 120 mm.

New names have been coined to describe the various hook shapes but there is much confusion and overlapping of names. 'Maxi' and 'Mega' are also terms for styles of hook shape but there is no common agreement about what these terms mean outside of each 'brand' name that employs them: what one brand terms a midi another calls a 'hook' but, basically, there are three types of hook. The near symmetrical 'U', a 'tight' or 'closed' toe shape, between 60° and 75° and an 'open' shape of 45°–55°. Where the toe is shorter the same toe angles are generally referred to as midi.

Set-back stick heads

The big headed 'Hook' also suffered for a short time from the appearance at the 1986 World Cup of the first sticks with set-back heads. There was not a significant impact but it (and others) added to the general confusion, as apparently 'everyone and his dog' were presenting new ideas in head shape. (Metal handled and fully composite sticks had not yet made an appearance so at the time the 'battle' was about head shape and length rather than materials and to a lesser extent, because hockey players at the time tended to be more 'traditionalist', the head/handle configuration. Even reinforcement with fiberglass and carbon fibre was not the issue it was later to become.

One hockey stick produced by AREC for the French inventor, Jean Capét, had the centre of the handle aligned with the centre of the horizontal length of the head. There was a lot of promotion based on 'rotational balance' and the 'sweet spot' and 'power hitting'. The 'Hook' certainly felt out of rotational balance, especially to those who had been playing with short-head sticks that had been made with a very thin toe, so as to concentrate the weight of the head closer to the shaft.

Aligning the centre of the handle with the centre of the horizontal length of a short-head, rather than with the centre of the ball created some unusual playing characteristics, for example, the reversed-stick ball position being further from the feet than the forehand ball position, which is the opposite of what happens with a conventional 'traditional' handle head configuration. (When the centre line of the handle aligns with the centre of the ball—or very nearly so—there is no or very little difference in ball position in relation to the stick or the feet of the player between the forehand and reverse playing positions.)

The AREC stick was initially produced without a significantly upturned toe and had a short horizontal length (approximately 105 mm), it was in this regard similar to standard short-head sticks of the time. The lack of an upturned toe, combined with the unusual reverse ball position, caused some difficulty in adapting to the stick and when the horizontal head lengths of sticks began to be made longer, by popular demand. A stick with the handle aligned to the centre of the head length was no longer practical for playing hockey. Manufacture of it as an outfield stick ceased in the early 1990s, probably by 1992 but similar sticks, by other manufacturers, have appeared for goalkeeper use.

Kinked-shaft & recurve heads

The traditional small arc to the heel edge of the hockey stick had the effect of setting the stick head back slightly. This aspect of stick design (of which the AREC hockey stick was an extreme example) was first explored just prior to the Men's Hockey World Cup of 1986 and resulted in the production of hockey sticks with a stick head considerably more set-back in relation to the handle. The original design, aligning the centre line of the handle with the centre of the ball, in the common striking position, featured a counterbalancing "kink" or protrusion to the handle on the toe edge of the handle, just above the head of the stick. This invention of the kinked-shaft and set-back head stick led directly to rules governing the amount of bend or "permitted deviation" to the "edge sides" of the hockey stick handle. Some of these were later termed "recurve" heads (a description given to a later style, produced by an Australian manufacturer, without the patented kink feature.)

The early extremes in stick design were in those sticks intended for use by goalkeepers. The aim was simply to present the maximum stopping area to the ball. The first was the extended hook (far left), which was made with a toe of approximately 150 mm (6 in). When sticks with an upturn substantially more than that (some more than half the length of the handle) began to appear, which was around 1988, the FIH placed a limit of 100 mm (4") on the upturn of the toe of the head.

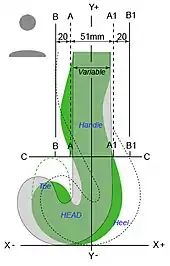

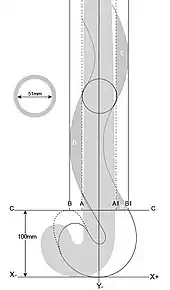

In 1990 a plywood cutout of a stick with multiple kinks in the shaft was presented to the FIH for comment, the intention was to produce it as a goalkeeper's stick. Having limited the toe upturn only two years previously the FIH saw this as mockery and issued a press release, in April 1990, proposing a ban on all hockey sticks with "non-straight" handles to take effect after the Barcelona Olympics of that year. There was protest from those who had been marketing sticks with set-back heads and or kinked shafts and it was in any case not a sensible proposal because there is no such thing as a hockey stick with a perfectly straight handle. The result was the withdrawal of the proposed ban and the imposition of "limits of deviation", which permitted one bend to either side of the handle to a maximum of 20 mm on each side. In 2000 a diagram explaining the permitted deviation was included in the Rules of Hockey. Previously the only restraint on the configuration of a hockey stick was that it had to pass through a ring of 2" diameter (later adjusted to 51 mm—2 in rounded up to the nearest millimeter).

Permitted deviation

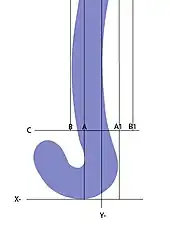

Although permitted deviation (from the straight) to the edges of a hockey stick (handle) were included in the 1991 Rules of Hockey, a diagram of a hockey stick, to illustrate what was permitted was not included until 2000 and then it was a part stick diagram placed horizontally on a page smaller than the A6 page of the present rulebook. The diagram was very poorly drawn but it was a significant step for the FIH to include it at all. The diagram remained unchanged until 2004, when the orientation was altered so that the stick was shown upright and it was also shown full length. The x-axis (previously vertical) became the ground plane and the y-axis a vertical line through the centre of the handle. Further improvements to the diagram (particularly the drawing of the representation of the stick and an illustration of possible curves to the handle) were made in 2006 and a second diagram, detailing head configuration, was added.

To describe the dimensions of head and handle the hockey stick is envisaged to be placed with the bottom curve of the stick head on a level surface, the x-axis, with the stick-handle perpendicular to it (the y-axis). The y-axis runs from an intersection with the x-axis (0) vertically through the midpoint of the top of the handle. The Head is the part from the x-axis to the line C-C (diagram) a vertical distance of 100 mm. This line C-C also describes the limit on any upturn to the toe of the head. By Rule there is no limit to the length of the stick head along the x-axis, but practical considerations, as well as technicalities related to the joining of the head and the Handle (on the line C-C), did create limitations with wooden sticks.

The extent of the stick head along the X+ axis, towards the 'heel' of the Head is confined by the rule requirement that the stick head and the handle meet in a smooth continuous fashion at the line C-C and by a rule restriction on the shape of the handle, which is that the stick-handle must not project beyond the line B1-B1. It is possible to envisage a stick where the width of handle did not extend beyond the line A1-A1, thus allowing a significant extension of the stick head along the X+ axis, but the practicalities of such a design seem to be limited and have not been explored. The length of the Head (or toe) along the X- axis has varied enormously, especially since the Second World War and again after the introduction of the timber lamination process in the early 1980s.

The stick handle may be bent or 'deviated', in a smooth curve only, once only to either side. That is the handle may have one out-moving curve on the 'heel' side of the head and one out-moving curve on the toe side. It is therefore possible to have a hockey stick with a handle deviation to the front or toe side or a handle deviation to the back or 'heel' side or a stick-handle that is bent once to both the toe and 'heel' sides.

The sample diagram on the right shows three deviating areas (a), (b), and (c). Any of these areas could exist on a stick by itself but, in this illustration, area (a) could legally coexist with area (b) and area (c) could coexist with area (b); but areas (a) and (c) could not legally coexist on the same stick because they are both on the same edge and only one protrusion either beyond the line AA or beyond the line A1A1—or both—is permitted on the handle.

The maximum permitted width of the handle (51 mm) is illustrated in the diagram by the distance between the dotted lines A-A and A1-A1. A hockey stick handle will rarely be of the maximum permitted width: most are between 46 mm and 48 mm at the widest point.

The maximum permitted 'deviation' is shown by the lines B-B and B1-B1 respectively. The line B-B is 20 mm further along the X- axis than the line A-A and the line B1-B1 is 20 mm further along the X+ axis than the line A1-A1. There is no limit to the length of a protrusion along the y-axis specified, so the deviation curve or curves may be of any length along the length of the stick-handle. Some goalkeeping sticks have an outward curve on the toe side (within the line B-B) that extends for almost half the total length of the stick.

The sample illustrated does not reach the line A1A1 on the 'heel edge' and the Y axis is not central to the shaft, which raises the question "How is the stick positioned for measurement of permitted deviation." The answer is that the vertical axis Y runs through the top centre of the handle and the stick is assumed to be suspended from that top centre point and perpendicular to the X axis (the ground), the curve to the base of the head of the stick being in contact with the ground, it is therefore not necessary for the Y axis to pass through the centre of the shaft just above the head of the stick, although in most traditional sticks it will do so (or very nearly do so—as 'rake' to the handle may cause the Y axis to run a few millimeters to the heel side of the true centre of the shaft). To October 2015 no official measuring method or device for measuring 'permitted deviation' has been approved by the FIH.

Permitted bow

Increasing the degree of bow to the face side (flat side) makes it easier to get high speeds from the drag-flick (a "sling-shot" style stroke started from behind the body of the flicker) and allows easier execution of the stroke. At first, after extreme bows were introduced (2005), the Hockey Rules Board (HRB) placed a limit of 50 mm on the maximum depth of such a bow over the length of the stick, but experience quickly demonstrated this degree of bend to be excessive.

The Rules of Hockey 2006 limited this particular curve of the stick to 25 mm so as to limit the power with which the ball can be flicked and to try to ensure that hitting control was maintained (the curvature to the face of the stick considerably influences the angle at which the stick head strikes through the ball). The placement of the maximum bow along the length of handle has now been specified in the Rules of Hockey at 20 cm above the head (the line C-C).

It is now illegal for any hockey stick to have a bow that exceeds 25 mm. The bow height is measured by placing the stick face-side to a flat surface and presenting the official measuring device, a 25 mm-high metal triangular or cylindrical measure, to the gap between the surface and the under-flat of the stick.

Since this article was first written in 2008, there have been attempts to get around the rule by the production of a stick which 'in a natural resting position' has a face side that is not parallel to the flat surface measured from but rests with the face at a sharp angle. The result of the sloping of the face side is to put one edge of it closer than 25 mm to the flat surface and permit a much deeper bow than would otherwise be possible. This flouts the intention of the rule, so it is possible that there may be a move to a measuring cylinder, under and across, the entire face of the stick.

There was a development in design called the 'low bow'. This placed the maximum bow of the stick much closer to the head than was previously the case, when it was positioned more centrally on the length of the stick. The effect of placing the maximum bow lower down the handle was to increase the angle at which the stick head was presented to the ball. The angle of presentation of a '25 mm low bow' was approximately the same as was achieved when the maximum permitted bow was 50 mm but the maximum was situated at about the mid-length of the stick.

Extreme bow has an effect on the ease with which stick-work and hitting of the ball (so that it stays on the ground) may be carried out. There has always been some bow to a stick handle, 10–20 mm was common (right in diagram) because to have a stick that was straight would make 'gathering' the ball, by pulling it towards the body from the left, more difficult and a bow in the other direction (a convex bow) would cause 'dragging' in stick-work and make hitting the ball cleanly difficult in the other.

A stick with a very small degree of bow (no more than 5 mm) was popular in the days when the clip hit in the outfield was a permitted stroke (a chip hit is a hit down on the top or back of the ball which causes it to rise sharply and produces under-spin, so that the ball does not run on when it lands). The increased use of the scoop when the lifted hit in the outfield was banned led to an increase in bow depth (and many players also found that a moderate bow aided stick-work as well). The maximum depth of this bow was generally at around the mid-length of the stick.

The 'low bow' has been popularized by the development of the drag-flick, particularly as a first shot on goal at a penalty corner. The Pakistan International player Sohail Abbas, who holds the record for the number of goals scored at international level, mostly scored with the set piece drag-flick, had such a stick made especially to his own requirements and many have copied his design—and tried to improve on it.

Although there can be no doubt that the 'slingshot' effect of a bowed stick, when the ball is 'dragged' from the rear of the feet and released after powerful body and arm rotation to the front of the feet, has dramatically increased the velocity at which the ball may be propelled by this flicking method, there may be considerable difficulty in hitting the ball along the ground with a very bowed stick. This may be of advantage when shooting at the goal with a lifted hit from within the 'circle' (which is legal) but a disadvantage when hitting the ball outside of the scoring 'circles', because it is illegal to intentionally lift the ball with a hit except when within the scoring 'circles' i.e. the opponent's 'circle'.

The upright forehand hitting stroke, which is commonly used when the ball is close to the feet, will seldom be made with the handle in the same plane as the ball, unless the ball is to the immediate right of the player i.e. beside or alongside his feet. (Stick shown on far right of illustration)—which is generally the case when the ball is being hit directly to the front or from left to right—with a bowed stick even this vertical handle position will present an angled head to the ball. The further away to the front of the player the ball is the greater will be the head angle presented to the ball. To deal with the problem of head presentation some players use a low 'roundhouse' style of hitting, rather than an upright style and may also employ sweep-hits or slap-hitting of the ball (the difference being the positioning of the hands, sweep hits are generally made with the hands together at the top of the stick and with the base of the stick head in contact with the ground, while slap-hits are usually made with the hands in the more spread dribbling grip and the stick head is not necessarily in contact with the ground, but it may be), either sweep or slap type strokes give greater control over the angle of the face of the stick as it makes contact with the ball and are often the preferred strokes when passing the ball over longer distances (over shorter distances—less than 20 m—a push stroke is often preferred).

The detail illustration shows that when the handle is angled away from the ball both the position of contact with the ball on the ball and the part of the face of the stick making contact will be altered. The greater the bow the greater the degree of adjustment the player must make to his swing and to the hitting position of the ball to achieve a hit flat along the ground.

Stages of development

The development of the modern hockey stick has not taken place in one continuous flow with each development following on from a previous one. Many things changed in the same time frame but at different speeds, especially some of the later developments. There have been more changes in stick design in the last twenty-five years than there were in the previous one hundred and twenty-five and the pace of change has been an ever increasing one. There will no doubt be further development, probably in materials, possibly because of changes to the rules. In roughly chronological order this is what has happened so far.

- 1860s: Hockey taken to India. Stick head made shorter; move from ash to mulberry timber for the stick head.

- Further shortening of stick head; heel of head made tighter. Taken as far as possible by 1986, when a move back towards a midi length began.

- 1960s: Reinforcement with fiberglass.

- 1970s: Reinforcement with carbon and aramid as well as glass fibres.

- 1980s: Stick heads made from glued lamination of wood in addition to the one piece heads

- 1982: Introduction of upturned toe, first the hook closely followed by midi and "J" shaped designs.

- 1980s: Limit placed on upturn of toe of head at 100 mm.

- 1986: Kinked shaft stick. Set back stick head.

- 1980s: Stick lengths other than 36", up to 39", become widely available and custom lengths 42"+ can be purchased.

- 1990: Permitted deviation rule—limited bends to edges of stick handle defined.

- 1990: Specialist goalkeeper's sticks introduced, the first being the ZigZag Save.

- 1980s: Metal handled stick with an inserted wooden head (plywood) introduced.

- 1994: Composite sticks fully accepted in rules after a two-year "experiment".

- 1990s: Metal handles banned.

- 2004: Rule redefining of head and handle. Head the part from the base of the curve perpendicular to 100 mm—handle the remainder of the stick.

- 2000s: Refinement of head shapes, probably five shapes available as "standard".

- 2000s: Number of wood core sticks in use declines as moulded "composites" become the norm.

- 2006: Bow of the face of the handle is increased to facilitate drag-flicking. Closely followed by a rule concerning maximum permitted bow; initially at 50 mm and subsequently at 25 mm.

- 2007: Low bow sticks introduced.

- 2011: Maximum stick bow position not permitted to be less than 8" (20 cm) above the head of the stick.

- 2013: Maximum permitted weight reduced to 737 g (26 oz)

- 2015: Maximum length limit of 41" (105 cm)introduced.

The forehand striking position

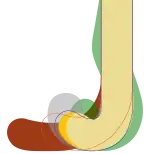

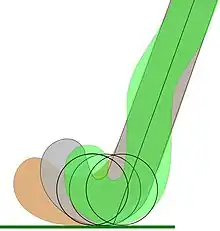

For the purposes of this article the ball will be assumed to be 73 mm in diameter. Ball size does play a significant part in stickwork and ball control (as does the weight and hardness of the ball) but an investigation of these is outside the scope of this article. The width of stick handles does vary (as does the horizontal length of stick heads) but for clarity and convenience the shaft of the handle just above the head has been taken as 46 mm, which is fairly common, and the sticks scaled from that measurement.

The position of the ball when it is played, particularly hit with the stick head, does, however have a bearing on stick head design. Using just one of the whole range of angles the ball may be struck at from the forehand (right-hand) side (45°), the position of the ball will be looked at in relation to both the centre of the head of the stick and a line projected to run through the centre of the handle. An examination on the position of wear on the base of stick heads that have been used over a period on an abrasive playing surface lead to the conclusion that the ball is positioned close to the center of the head length of the modern stick. This is also the more usual position for receiving or stopping the ball in play while in the 'dribbling crouch'. Obviously when the handle is vertical or horizontal there is considerable variation but in most common hitting and dribbling positions the line of the uppermost edge of the handle projects close to the centre of the ball.

One of the problems with a striking head that is significantly narrower than the diameter of the ball is that the ball is easily lifted unintentionally if struck with the face of the stick head inclined backward, 'open', rather than vertical or nearly so. Striking the ball with a 'closed' face is not always a solution, because it is then possible to 'squeeze' or 'clip' it, again causing the ball to rise, possibly even more steeply than with the so-called 'undercut' hit.

Another difficulty is striking the ball accurately at the point on the stick head that is intended (the usual range of error can be seen, in the diagram, in the difference of the lengths of the red lines that run from the centre of the two differently positioned stick heads).

It is also necessary to avoid unintentionally turning the handle during a hit at the ball so that the ball is "sliced" (to the right) or hooked (to the left), this is achieved by gripping the stick firmly, generally with one hand locked against the other at the top of the handle, at the moment of impact with the ball.

Ensuring vertical and flat (perpendicular to intended direction of ball travel) contact with the ball is in the hands of the player and the coach, but achieving a correct contact position between the stick head and the ball can be helped by the design of the stick.

At a common playing angle three different styles of hook stick head present identical ball/handle relationships because the bend of the 'heel' is the same in each stick. An increase in the height of the toe over the ball is very noticeable and is most pronounced in the more 'open' shape. The modern hook does not suffer from the effects of a rotational imbalance in the head as much as the original did because stick heads are now generally tapered towards the toe, rather than of uniform thickness so toe height is not, from a weight and rotational balance point of view, as much of an issue as it once might have been. The stick head is also generally tapered from the midpoint of the striking area towards the bottom curve, so when the stick is in the reversed position the maximum thickness of the head is not at the highest point. This gives a more balanced rotation of the weight of the stick head over the ball.

Some of the early hooks were actually thinner in the centre and became thicker in the toe; it is likely that this was done to facilitate more powerful reversed-stick hitting of the ball but it gave the stick unusual handling characteristics when turning it over the ball and back in "stickwork": an "overturning" or "throw" of the stick head had to be taken into account. The composite stick is generally lighter than the previous wood versions and it is unusual these days to find a young player using the 25–26 oz sticks that were quite commonly used on grass in the 1970s, especially by those likely to be regularly taking hits at a stationary ball.

Field hockey stick brands

The majority of modern hockey sticks are manufactured in Asia (Pakistan, India, and China predominantly). Manufacturers will often produce sticks for a number of different brands.

See also

References

- International Hockey Federation (1 January 2019). "Rules of Hockey including explanations". England Hockey. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Rules of Hockey 2015-2016