County Fermanagh

County Fermanagh (/fərˈmænə/ fər-MAN-ə; from Irish: Fir Manach / Fear Manach, meaning 'men of Manach') is one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of six counties of Northern Ireland

County Fermanagh

| |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Nickname: The Lakeland County | |

| Motto(s): | |

| |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Northern Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| Established | 1584/85 |

| County town | Enniskillen |

| Area | |

| • Total | 715 sq mi (1,851 km2) |

| • Land | 653 sq mi (1,691 km2) |

| • Rank | 25th |

| Highest elevation (Cuilcagh) | 2,182 ft (665 m) |

| Population (2021) | 63,585 |

| • Rank | 28th[1] |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode area | |

| Area code | 028 |

| Website | discovernorthernireland |

| Contae Fhear Manach is the Irish name; Countie Fermanagh,[2] Coontie Fermanagh[3] and Coontie Fermanay[4] are Ulster Scots spellings (the latter used only by Dungannon & South Tyrone Borough Council). | |

The county covers an area of 1,691 km2 (653 sq mi) and had a population of 63,585 as of 2021.[5][6] Enniskillen is the county town and largest in both size and population.

Fermanagh is one of four counties of Northern Ireland to have a majority of its population from a Catholic background, according to the 2011 census.[1]

Geography

Fermanagh spans an area of 1,851 km2 (715 sq; mi), accounting for 13.2% of the landmass of Northern Ireland. Nearly a third of the county is covered by lakes and waterways, including Upper and Lower Lough Erne and the River Erne. Forests cover 14% of the landmass (42,000 hectares).[7] It is the only county in Northern Ireland that does not border Lough Neagh.

The county has three prominent upland areas:

- the expansive West Fermanagh Scarplands to the southwest of Lough Erne, which rise to about 350m,

- the Sliabh Beagh hills, situated to the east on the Monaghan border, and

- the Cuilcagh mountain range, located along Fermanagh's southern border, which contains Cuilcagh, the county's highest point, at 665m.

The county borders:

- County Tyrone to the north-east,

- County Monaghan to the south-east,

- County Cavan to the south-west,

- County Leitrim to the west, and

- County Donegal to the north-west.

Fermanagh is by far the least populous of Northern Ireland's six counties, with just over one-third the population of Armagh, the next least populous county.

It is approximately 120 km (75 mi) from Belfast and 160 km (99 mi) from Dublin. The county town, Enniskillen, is the largest settlement in Fermanagh, situated in the middle of the county.

The county enjoys a temperate oceanic climate (Cfb') with cool winters, mild humid summers, and a lack of temperature extremes, according to the Köppen climate classification.

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty manages three sites of historic and natural beauty in the county: Crom Estate, Florence Court, and Castle Coole.

Geology

The oldest sediments in the county are found north of Lough Erne. These so-called red beds were formed approximately 550 million years ago. Extensive sandstone can be found in the eastern part of the county, laid down during the Devonian, 400 million years ago. Much of the rest of the county's sediments are shale and limestone dating from the Carboniferous, 354 to 298 million years ago. These softer sediments have produced extensive cave systems such as the Shannon Cave, the Marble Arch Caves and the Caves of the Tullybrack and Belmore hills. The carboniferous shale exists in several counties of northwest Ireland, an area known colloquially as the Lough Allen basin. The basin is estimated to contain 9.4 trillion cubic metres of natural gas, equivalent to 1.5 billion barrels of oil.[8]

The county is situated over a sequence of prominent faults, primarily the Killadeas – Seskinore Fault, the Tempo – Sixmilecross Fault, the Belcoo Fault and the Clogher Valley Fault which cross-cuts Lough Erne.

History

The Menapii are the only known Celtic tribe specifically named on Ptolemy's 150 AD map of Ireland, where they located their first colony—Menapia—on the Leinster coast circa 216 BC. They later settled around Lough Erne, becoming known as the Fir Manach, and giving their name to Fermanagh and Monaghan. Mongán mac Fiachnai, a 7th-century King of Ulster, is the protagonist of several legends linking him with Manannán mac Lir. They spread across Ireland, evolving into historic Irish (also Scottish and Manx) clans.

The Annals of Ulster which cover medieval Ireland between AD 431 to AD 1540 were written at Belle Isle on Lough Erne near Lisbellaw.

Fermanagh was a stronghold of the Maguire clan and Donn Carrach Maguire (died 1302) was the first of the chiefs of the Maguire dynasty. However, on the confiscation of lands relating to Hugh Maguire, Fermanagh was divided in a similar manner to the other five escheated counties among Scottish and English undertakers and native Irish. The baronies of Knockninny and Magheraboy were allotted to Scottish undertakers, those of Clankelly, Magherastephana and Lurg to English undertakers and those of Clanawley, Coole, and Tyrkennedy, to servitors and natives. The chief families to benefit under the new settlement were the families of Cole, Blennerhasset, Butler, Hume, and Dunbar.

Fermanagh was made into a county by a statute of Elizabeth I, but it was not until the time of the Plantation of Ulster that it was finally brought under civil government.

The closure of all the lines of Great Northern Railway (Ireland) within County Fermanagh in 1957 left the county as the first non-island county in the UK without a railway service.

Administration

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1653 | 5,498 | — |

| 1659 | 7,102 | +29.2% |

| 1821 | 130,997 | +1744.5% |

| 1831 | 149,763 | +14.3% |

| 1841 | 156,481 | +4.5% |

| 1851 | 116,047 | −25.8% |

| 1861 | 105,768 | −8.9% |

| 1871 | 92,794 | −12.3% |

| 1881 | 84,879 | −8.5% |

| 1891 | 74,170 | −12.6% |

| 1901 | 65,430 | −11.8% |

| 1911 | 61,836 | −5.5% |

| 1926 | 57,984 | −6.2% |

| 1937 | 54,569 | −5.9% |

| 1951 | 53,044 | −2.8% |

| 1961 | 51,531 | −2.9% |

| 1966 | 49,886 | −3.2% |

| 1971 | 50,255 | +0.7% |

| 1981 | 51,594 | +2.7% |

| 1991 | 54,033 | +4.7% |

| 2001 | 57,527 | +6.5% |

| 2011 | 61,805 | +7.4% |

| 2021 | 63,585 | +2.9% |

| [9][10][11][12][13][14] | ||

The county was administered by Fermanagh County Council from 1899 until the abolition of county councils in Northern Ireland in 1973.[15] With the creation of Northern Ireland's district councils, Fermanagh District Council became the only one of the 26 that contained all of the county from which it derived its name. After the re-organisation of local government in 2015, Fermanagh was still the only county wholly within one council area, namely Fermanagh and Omagh District Council, albeit that it constituted only a part of that entity.

For the purposes of elections to the UK Parliament, the territory of Fermanagh is part of the Fermanagh and South Tyrone Parliamentary Constituency. This constituency elected Provisional IRA hunger-striker Bobby Sands as a member of parliament in the April 1981 Fermanagh and South Tyrone by-election, shortly before his death.

Demographics

2011 census

On Census Day 27 March 2011, the usually resident population of Fermanagh Local Government District, the borders of the district were very similar to those of the traditional County Fermanagh, was 61,805. Of these:[12]

- 0.93% were from an ethnic minority population and the remaining 99.07% were white (including Irish Traveller)

- 59.16% belong to or were brought up in the Catholic religion and 37.78% belong to or were brought up in a 'Protestant and Other Christian (including Christian related)' religion

- 37.20% indicated that they had a British national identity, 36.08% had an Irish national identity and 29.53% had a Northern Irish national identity

2021 Census

On Census Day (2021), the usually resident population of Fermanagh Local Government District, the borders of the district were very similar to those of the traditional County Fermanagh, was 63,585. Of these:[16]

- 58.8% belong to or were brought up in the Catholic religion and 35.5% belong to or were brought up in a 'Protestant and Other Christian (including Christian related)' religion.

Community background and religion

| Religion or religion brought up in | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 37,399 | 58.8 |

| Protestant and Other Christian | 22,559 | 35.5 |

| None (no religion) | 2,947 | 4.6 |

| Other | 680 | 1.1 |

| Total | 63,585 | 100.0 |

| Religion | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 55,892 | 87.9 |

| Catholic | 35,412 | 55.7 |

| Church of Ireland | 13,065 | 20.5 |

| Methodist | 2,552 | 4.0 |

| Presbyterian | 1,989 | 3.1 |

| Other Christian (including Christian related) | 2,874 | 4.5 |

| Protestant and Other Christian: Total | 20,480 | 32.2 |

| Other | 601 | 0.9 |

| Islam | 216 | 0.3 |

| Hinduism | 50 | 0.08 |

| Other religions | 335 | 0.5 |

| None/not stated | 7,092 | 11.2 |

| No religion | 5,885 | 9.3 |

| Religion not stated | 1,207 | 1.9 |

| Total | 63,585 | 100.0 |

Ethnicity

| Ethnic group | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| White: Total | 62,583 | 98.4 |

| White: British/Irish/Northern Irish/English/Scottish/Welsh (with or without non-UK or Irish national identities) |

60,244 | 94.7 |

| White: Other | 2,199 | 3.5 |

| White: Irish Traveller | 135 | 0.2 |

| White: Roma | 4 | 0.006 |

| Other ethnic groups: Total | 1,002 | 1.6 |

| Asian or Asian British | 501 | 0.8 |

| Black or Black British | 122 | 0.2 |

| Mixed | 304 | 0.5 |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 75 | 0.1 |

| Total | 63,585 | 100.0 |

Country of birth

| Country of birth | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom and Ireland | 60,433 | 95.0 |

| Northern Ireland | 52,063 | 81.9 |

| England | 3,477 | 5.5 |

| Scotland | 420 | 0.7 |

| Wales | 98 | 0.2 |

| Republic of Ireland | 4,375 | 6.9 |

| Europe | 2,139 | 3.4 |

| European Union | 2,047 | 3.2 |

| Other non-EU countries | 92 | 0.2 |

| Rest of World | 1,013 | 1.6 |

| Middle East and Asia | 468 | 0.7 |

| North America, Central America and Caribbean | 243 | 0.4 |

| Africa | 187 | 0.3 |

| Antarctica, Oceania and Other | 85 | 0.1 |

| South America | 30 | 0.05 |

| Total | 63,585 | 100.0 |

Main languages

| Main language | Usual residents aged 3+ | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| English | 59,081 | 96.4 |

| Polish | 649 | 1.1 |

| Lithuanian | 389 | 0.6 |

| Bulgarian | 200 | 0.3 |

| Irish | 138 | 0.2 |

| Latvian | 115 | 0.2 |

| All other languages | 745 | 1.2 |

| Total (usual residents aged 3+) | 61,316 | 100.0 |

Knowledge of Irish

| Ability in Irish | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Speaks, reads, writes and understands Irish | 2,703 | 4.4 |

| Speaks and reads but does not write Irish | 509 | 0.8 |

| Speaks but does not read or write Irish | 2,336 | 3.8 |

| Understands but does not read, write or speak Irish | 3,114 | 5.1 |

| Other combination of skills | 929 | 1.5 |

| Has some knowledge of Irish: Total | 9,591 | 15.6 |

| No ability in Irish | 51,725 | 84.4 |

| Total (usual residents aged 3+) | 61,316 | 100.0 |

Knowledge of Ulster Scots

| Ability in Ulster Scots | Number | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Speaks, reads, writes and understands Ulster Scots | 490 | 0.8 |

| Speaks and reads but does not write Ulster Scots | 319 | 0.5 |

| Speaks but does not read or write Ulster Scots | 1,194 | 1.9 |

| Understands but does not read, write or speak Ulster Scots | 2,468 | 4.0 |

| Other combination of skills | 395 | 0.6 |

| Has some knowledge of Ulster Scots: Total | 4,866 | 7.9 |

| No ability in Ulster Scots | 56,450 | 92.1 |

| Total (usual residents aged 3+) | 61,316 | 100.0 |

National identity

| National identity | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Irish only | 24,341 | 38.3% |

| British only | 16,678 | 26.2% |

| Northern Irish only | 13,543 | 21.3% |

| British and Northern Irish only | 2,863 | 4.5% |

| Irish and Northern Irish only | 1,168 | 1.8% |

| British, Irish and Northern Irish only | 602 | 0.9% |

| British and Irish only | 305 | 0.5% |

| Other identity | 4,086 | 6.4% |

| Total | 63,585 | 100.0% |

| All Irish identities | 26,653 | 41.9% |

| All British identities | 20,920 | 32.9% |

| All Northern Irish identities | 18,481 | 29.1% |

Industry and tourism

Agriculture and tourism are two of the most important industries in Fermanagh. The main types of farming in the area are beef, dairy, sheep, pigs and some poultry. Most of the agricultural land is used as grassland for grazing and silage or hay rather than for other crops.

The waterways are extensively used by cabin cruisers, other small pleasure craft and anglers. The main town of Fermanagh is Enniskillen (Inis Ceithleann, 'Ceithleann's island'). The island town hosts a range of attractions including the Castle Coole Estate and Enniskillen Castle, which is home to the museum of The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and the 5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards. Fermanagh is also home to The Boatyard Distillery, a distillery producing gin.

Attractions outside Enniskillen include:

Settlements

Villages

(population of 1,000 or more and under 2,500 at 2011 Census)[21]

Small villages or hamlets

(population of less than 1,000 at 2011 Census)[21]

- Aghadrumsee

- Arney

- Ballycassidy

- Belcoo

- Bellanaleck

- Belleek

- Boho

- Brookeborough

- Clabby

- Coa

- Derrygonnelly

- Derrylin

- Donagh

- Ederney

- Florencecourt

- Garrison

- Killadeas

- Kinawley

- Lack

- Letterbreen

- Lisnarick

- Magheraveely

- Monea

- Newtownbutler

- Pettigo (partially)

- Rosslea

- Springfield

- Tamlaght

- Teemore

- Tempo

- Wattlebridge

Subdivisions

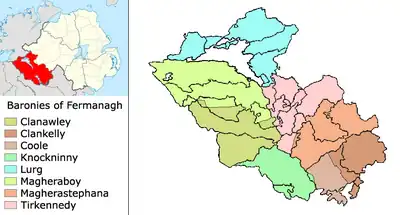

Baronies

Parishes

Townlands

Sport

Fermanagh GAA has never won a Senior Provincial or an All-Ireland title in any Gaelic games.

Only Ballinamallard United F.C. take part in the Northern Ireland football league system. All other Fermanagh clubs play in the Fermanagh & Western FA league systems. Fermanagh Mallards F.C. played in the Women's Premier League until 2013.

Enniskillen RFC was founded in 1925 and is still going.[22] There is also a rugby league team, the Fermanagh Redskins

Famous football players from Fermanagh include –

Notable people

Famous people born, raised in or living in Fermanagh include:

- John Armstrong (1717–1795), born in Fermanagh, Major General in the Continental Army and delegate in the Continental Congress[23]

- Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), author and playwright from Foxrock in Dublin, educated at Portora Royal School

- Darren Breslin, traditional musician

- The 1st Viscount Brookeborough, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, 1943–1963

- Denis Parsons Burkitt (1911–1993), doctor, discoverer of Burkitt's lymphoma

- Roy Carroll (born 1977), association footballer

- Edward Cooney (1867–1960), evangelist and early leader of the Cooneyite and Go-Preachers

- Brian D'Arcy (born 1945), C.P., Passionist priest and media personality

- Brendan Dolan (born 1973), professional darts player for the PDC

- Adrian Dunbar (born 1958), actor

- Arlene Foster, Baroness Foster of Aghadrumsee (born 1970), politician

- Neil Hannon (born 1970), musician

- Robert Kerr (1882–1963), athlete and Olympic gold medalist

- Kyle Lafferty (born 1987), Northern Ireland International association footballer

- Charles Lawson (born 1959), actor (plays Jim McDonald in Coronation Street)

- Francis Little (1822–1890), born in Fermanagh, Wisconsin State Senator

- Terence MacManus (c. 1823–1861), leader in Young Irelander Rebellion of 1848

- Michael Magner (1840–97), recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Peter McGinnity, Gaelic footballer, Fermanagh's first winner of an All-Star Award

- Martin McGrath, Gaelic footballer, All-Star winner

- Ciarán McMenamin (born 1975), actor

- Gilla Mochua Ó Caiside (12th century), poet

- Aurora Mulligan, director

- Barry Owens, Gaelic footballer, two-time All-Star winner

- Sean Quinn (born 1947), entrepreneur

- Michael Sleavon (1826–1902), recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Patrick Treacy, author and one-time physician to Michael Jackson

- Joan Trimble (1915–2000), pianist and composer

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), author and playwright, educated at Portora Royal School

- Gordon Wilson (1927–1995), peace campaigner and Irish senator

Surnames

The most common surnames in County Fermanagh at the time of the United Kingdom Census of 1901 were:[24]

Railways

The railway lines in County Fermanagh connected Enniskillen railway station with Derry from 1854, Dundalk from 1861, Bundoran from 1868 and Sligo from 1882.[25]

The railway companies that served the county, prior to the establishment by the merger of Londonderry and Enniskillen Railway, Enniskillen and Bundoran Railway the Dundalk and Enniskillen Railway which was later named the Irish North Western Railway, thus forming the Great Northern Railway (Ireland). By 1883 the Great Northern Railway (Ireland) absorbed all the lines except the Sligo, Leitrim and Northern Counties Railway, which remained independent throughout its existence.

In October 1957 the Government of Northern Ireland closed the GNR line, which made it impossible for the SL&NCR continue and forced it also to close.[26]

The nearest railway station to Enniskillen is Sligo station which is served by trains to Dublin Connolly and is operated by Iarnród Éireann. The Dublin-Sligo railway line has a two-hourly service run by Iarnród Éireann. The connecting bus from Sligo via Manorhamilton to Enniskillen is route 66 operated by Bus Éireann.

See also

- Abbeys and priories in Northern Ireland (County Fermanagh)

- Castles in County Fermanagh

- Extreme points of the United Kingdom

- High Sheriff of Fermanagh

- List of parishes of County Fermanagh

- List of places in County Fermanagh

- List of townlands in County Fermanagh

- Lord Lieutenant of Fermanagh

- People from County Fermanagh

Notes

- "Background Information on Northern Ireland Society – Population and Vital Statistics". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "North-South Ministerial Council: 2004 Annual Report in Ulster Scots" (PDF). Northsouthministerialcouncil.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Tourism Ireland: Yierly Report 2007". Tourismireland.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Dungannon & South Tyrone Borough Council". Dungannon.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "County". NISRA. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- "Build or find Census 2021 tables | NISRA Flexible Table Builder". build.nisra.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- "County Fermanagh – definition of County Fermanagh by The Free Dictionary". Thefreedictionary.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- "What's your fracking problem?". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- For 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years, Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy 14 March 1865.

- "Central Statistics Office: 2011 Census". Cso.ie. Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Histpop – The Online Historical Population Reports Website". Histpop.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- "Census 2011 Population Statistics for Fermanagh Local Government District". NISRA. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v3.0. © Crown copyright. - Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A. (eds.). Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November 1984). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850". The Economic History Review. 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. hdl:10197/1406. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012.

- "Local Government Act (Northern Ireland) 1972". Legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "Religion or religion brought up in". NISRA. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

- "National Identity (Northern Irish)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- "National Identity (British)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- "National Identity (Irish)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- "National identity (person based) - basic detail (classification 1)". NISRA. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- "Statistical classification of settlements". NI Neighbourhood Information Service. Archived from the original on 17 February 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- "StackPath". www.enniskillenrfc.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- "Fermanagh Genealogy Resources & Parish Registers | Ulster". Forebears.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- Hajducki, S. Maxwell (1974). A Railway Atlas of Ireland. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. maps 6, 7, 12. ISBN 0-7153-5167-2.

- Sprinks, N.W. (1970). Sligo, Leitrim and Northern Counties Railway. Billericay: Irish Railway Record Society (London Area).

References

- Clogher Record

- "Fermanagh" A Dictionary of British Place-Names. A. D. Mills. Oxford University Press, 2003. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Northern Ireland Public Libraries. 25 July 2007

- "Fermanagh" Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition. 25 July 2007 <Britannica Library>.

- Fermanagh: its special landscapes: a study of the Fermanagh countryside and its heritage /Department of the Environment for Northern Ireland. – Belfast: HMSO, 1991 ISBN 0-337-08276-6

- Livingstone, Peadar. – The Fermanagh story:a documented history of the County Fermanagh from the earliest times to the present day – Enniskillen: Cumann Seanchais Chlochair, 1969.

- Lowe, Henry N. – County Fermanagh 100 years ago: a guide and directory 1880. – Belfast: Friar's Bush Press, 1990. ISBN 0-946872-29-5

- Parke, William K. – A Fermanagh Childhood. Derrygonnelly, Co Fermanagh: Friar's Bush Press, 1988. ISBN 0-946872-12-0

- Impartial Reporter

- Fermanagh Herald