Ishikawa diagram

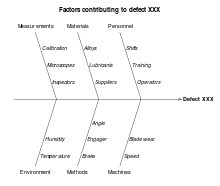

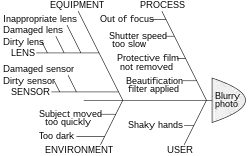

Ishikawa diagrams (also called fishbone diagrams,[1] herringbone diagrams, cause-and-effect diagrams) are causal diagrams created by Kaoru Ishikawa that show the potential causes of a specific event.[2]

| Ishikawa diagram | |

|---|---|

| |

| One of the Seven Basic Tools of Quality | |

| First described by | Kaoru Ishikawa |

| Purpose | To break down (in successive layers of detail) root causes that potentially contribute to a particular effect |

Common uses of the Ishikawa diagram are product design and quality defect prevention to identify potential factors causing an overall effect. Each cause or reason for imperfection is a source of variation. Causes are usually grouped into major categories to identify and classify these sources of variation.

Overview

The defect, or the problem to be solved,[1] is shown as the fish's head, facing to the right, with the causes extending to the left as fishbones; the ribs branch off the backbone for major causes, with sub-branches for root-causes, to as many levels as required.[3]

Ishikawa diagrams were popularized in the 1960s by Kaoru Ishikawa,[4] who pioneered quality management processes in the Kawasaki shipyards, and in the process became one of the founding fathers of modern management.

The basic concept was first used in the 1920s, and is considered one of the seven basic tools of quality control.[5] It is known as a fishbone diagram because of its shape, similar to the side view of a fish skeleton.

Mazda Motors famously used an Ishikawa diagram in the development of the Miata (MX5) sports car.[6]

Root causes

Root-cause analysis is intended to reveal key relationships among various variables, and the possible causes provide additional insight into process behavior. It shows high-level causes that lead to the problem encountered by providing a snapshot of the current situation.[1]

There can be considerable confusion about the relationships between problems, causes, symptoms and effects. Smith[7] highlights this and the common question, “Is that a problem or a symptom?” This question mistakenly presumes that problems and symptoms are contrasting categories, like light and heavy, such that something can’t be both. A problem is a situation that bears improvement; a symptom is the effect of a cause: a situation can be both a problem and a symptom.

At a practical level, a cause is whatever is responsible for, or explains, an effect - a factor "whose presence makes a critical difference to the occurrence of an outcome".[8]

The causes emerge by analysis, often through brainstorming sessions, and are grouped into categories on the main branches off the fishbone. To help structure the approach, the categories are often selected from one of the common models shown below, but may emerge as something unique to the application in a specific case.

Each potential cause is traced back to find the root cause, often using the 5 Whys technique.[9]

Typical categories include:

The 5 Ms (used in manufacturing)

Originating with lean manufacturing and the Toyota Production System, the 5 Ms is one of the most common frameworks for root-cause analysis:[10]

- Manpower / Mindpower (physical or knowledge work, includes: kaizens, suggestions)

- Machine (equipment, technology)

- Material (includes raw material, consumables, and information)

- Method (process)

- Measurement / medium (inspection, environment)

These have been expanded by some to include an additional three, and are referred to as the 8 Ms:[11]

- Mission / mother nature (purpose, environment)

- Management / money power (leadership)

- Maintenance

The 8 Ps (used in product marketing)

This common model for identifying crucial attributes for planning in product marketing is often also used in root-cause analysis as categories for the Ishikawa diagram:[11]

- Product (or service)

- Price

- Place

- Promotion

- People (personnel)

- Process

- Physical evidence (proof)

- Performance

The 4 or 5 Ss (used in service industries)

An alternative used for service industries, uses four categories of possible cause:[12]

- Surroundings

- Suppliers

- Systems

- Skill

- Safety

Citations

- Project Management Institute 2015, pp. 20–24, §2.4.4.2 Cause-and-Effect Diagrams.

- Ishikawa, Kaoru (1968). Guide to Quality Control. Tokyo: JUSE.

- Ishikawa, Kaoru (1976). Guide to Quality Control. Asian Productivity Organization. ISBN 92-833-1036-5.

- Hankins, Judy (2001). Infusion Therapy in Clinical Practice. p. 42.

- Tague, Nancy R. (2004). "Seven Basic Quality Tools". The Quality Toolbox. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: American Society for Quality. p. 15. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- Frey, Daniel D.; Fukuda, S.; Rock, Georg (2011). Improving complex systems today : proceedings of the 18th ISPE International Conference on Concurrent Engineering. Springer-Verlag London. ISBN 978-0857297990. OCLC 769756418.

- Smith, Gerald F. "Determining the cause of quality problems: lessons from diagnostic disciplines." Quality Management Journal 5.2 (1998): 24-41.

- Schustack, Miriam W. "Thinking about causality." The psychology of human thought (1988): 92-115.

- "Fishbone diagram: Solving problems properly". IONOS Startupguide. Retrieved 2021-12-23.

- Weeden, Marcia M. (1952). Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEAs) for small business owners and non-engineers : determining and preventing what can go wrong. ISBN 0873899180. OCLC 921141300.

- Bradley, Edgar (2016-11-03). Reliability engineering : a life cycle approach. ISBN 978-1498765374. OCLC 963184495.

- Dudbridge, Michael (2011). Handbook of Lean Manufacturing in the Food Industry. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444393118. OCLC 904826764.

References

- Ishikawa, Kaoru (1990); (Translator: J. H. Loftus); Introduction to Quality Control; 448 p; ISBN 4-906224-61-X OCLC 61341428

- Dale, Barrie G. et al. (2007); Managing Quality 5th ed; ISBN 978-1-4051-4279-3 OCLC 288977828

- Project Management Institute (2015-01-01). Business Analysis for Practitioners. Project Management Inst. ISBN 978-1-62825-069-5.