Fishing net

A fishing net is a net used for fishing. Some fishing nets are also called fish traps, for example fyke nets. Fishing nets are usually meshes formed by knotting a relatively thin thread. Early nets were woven from grasses, flaxes and other fibrous plant material. Later cotton was used. Modern nets are usually made of artificial polyamides like nylon, although nets of organic polyamides such as wool or silk thread were common until recently and are still used.

History

Fishing nets have been used widely in the past, including by stone age societies. The oldest known fishing net is the net of Antrea, found with other fishing equipment in the Karelian town of Antrea, Finland, in 1913. The net was made from willow, and dates back to 8300 BC.[1] Recently, fishing net sinkers from 27,000 BC were discovered in Korea, making them the oldest fishing implements discovered, to date, in the world.[2] The remnants of another fishing net dates back to the late Mesolithic, and were found together with sinkers at the bottom of a former sea.[3][4] Some of the oldest rock carvings at Alta (4200–500 BC) have mysterious images, including intricate patterns of horizontal and vertical lines sometimes explained as fishing nets. American Native Indians on the Columbia River wove seine nets from spruce root fibers or wild grass, again using stones as weights. For floats they used sticks made of cedar which moved in a way which frightened the fish and helped keep them together.[5] With the help of large canoes, pre-European Maori deployed seine nets which could be over one thousand metres long. The nets were woven from green flax, with stone weights and light wood or gourd floats, and could require hundreds of men to haul.[6]

Fishing nets are well documented in antiquity. They appear in Egyptian tomb paintings from 3000 BC. In ancient Roman literature, Ovid makes many references to fishing nets, including the use of cork floats and lead weights.[7][8][9] Pictorial evidence of Roman fishing comes from mosaics which show nets.[10] In a parody of fishing, a type of gladiator called retiarius was armed with a trident and a cast net. He would fight against a secutor or the murmillo, who carried a short sword and a helmet with the image of a fish on the front.[11] Between 177 and 180 the Greek author Oppian wrote the Halieutica, a didactic poem about fishing. He described various means of fishing including the use of nets cast from boats, scoop nets held open by a hoop, and various traps "which work while their masters sleep". Here is Oppian's description of fishing with a "motionless" net:

The fishers set up very light nets of buoyant flax and wheel in a circle round about while they violently strike the surface of the sea with their oars and make a din with sweeping blow of poles. At the flashing of the swift oars and the noise the fish bound in terror and rush into the bosom of the net which stands at rest, thinking it to be a shelter: foolish fishes which, frightened by a noise, enter the gates of doom. Then the fishers on either side hasten with the ropes to draw the net ashore.

In Norse mythology the sea giantess Rán uses a fishing net to trap lost sailors. References to fishing nets can also be found in the New Testament.[12] Jesus Christ was reputedly a master in the use of fishing nets. The tough, fibrous inner bark of the pawpaw was used by Native Americans and settlers in the Midwest for making ropes and fishing nets.[13][14] The archaeological site at León Viejo (1524–1610) has fishing net artifacts including fragments of pottery used as weights for fishing nets.

Fishing nets have not evolved greatly, and many contemporary fishing nets would be recognized for what they are in Neolithic times. However, the fishing lines from which the nets are constructed have hugely evolved. Fossilised fragments of "probably two-ply laid rope of about 7 mm diameter" have been found in one of the caves at Lascaux, dated about 15,000 BC.[15] Egyptian rope dates back to 4000 to 3500 BC and was generally made of water reed fibers. Other rope in antiquity was made from the fibers of date palms, flax, grass, papyrus, leather, or animal hair. Rope made of hemp fibres was in use in China from about 2800 BC.

In modern times, hemp was almost the only material in large scale use in fishing gear until 1900 when it found competition from cotton. By 1950s cotton had taken over a large fraction of fishing nets, although hemp nets were still in use in large quantities.[16] The first nylon fishing nets emerged in Japan in 1949 (although tests of similar equipment were taking place around the world in the last years of the 1940s). In the 1950s they were adopted worldwide, replacing nets made from cotton or hemp that were used before. The introduction of synthetic fibres in fishing gear from around 1950 changed a way of using natural materials that goes back several thousands of years. In the following decades (for example in Norway in 1975, 95% of all fishing gear was made of synthetic fibre), the new synthetic materials conquered the hegemony in net fishing.[16]

| Fishing nets in the past |

|---|

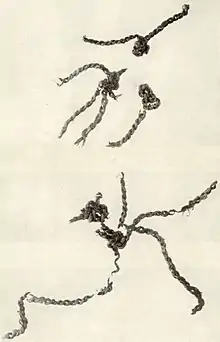

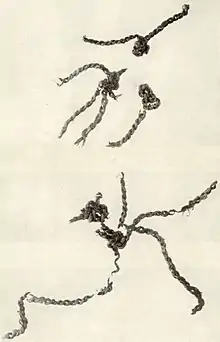

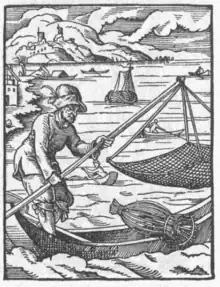

Fragments from the net of Antrea 8300 BC  Tacuinum sanitatis casanatensis, Baghdad, 14th century  Albrecht Dürer c. 1490-1493  Medieval Scandinavian ice fishing technique 1555  Fisherman with net and trap in Germany, 1568  The Chinese fishing nets of Fort Cochin, India (depiction from the 1840s)  Crab fishing, 1891–1895  Native American fishing salmon with loop net 1938 |

Types

| Type | Image | Target fish | Description | Environmental impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom trawl |  |

Demersal fish such as groundfish, cod, squid, halibut and rockfish | A trawl is a large net, conical in shape, designed to be towed along the sea bottom. The trawl is pulled through the water by one or more boats, called trawlers or draggers. The activity of pulling the trawl through the water is called trawling or dragging. | Bottom trawling results in a lot of bycatch and can damage the sea floor. A single pass along the seafloor can remove 5 to 25% of the seabed life.[17] A 2005 report of the UN Millennium Project, commissioned by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, recommended the elimination of bottom trawling on the high seas by 2006 to protect seamounts and other ecologically sensitive habitats. In mid-October 2006, US President Bush joined other world leaders calling for a moratorium on deep-sea trawling. |

| Cast net |  |

Schooling and other small fish | Cast nets (throw nets) are small round nets with weights on the edges which are thrown by the fisher. Sizes vary up to about four metres in diameter. The net is thrown by hand in such a manner that it spreads out on the water and sinks. Fish are caught as the net is hauled back in.[18] | High discrimination possible. Non targeted fish can be released unharmed. |

| Coracle net fishing |  |

Coracle fishing is performed by two people, each seated in a coracle, plying their paddle with one hand and holding a shared net with the other. When a fish is caught, each hauls up their end of the net until the two coracles are brought to touch and the fish is secured. | ||

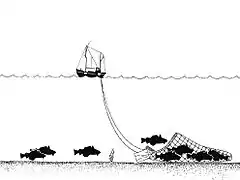

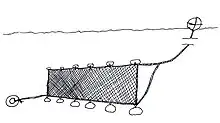

| Dragnet |  |

This is a general term which can be applied to any net which is dragged or hauled across a river or along the bottom of a lake or sea. An example is the seine net shown in the image. The fishing depth of this net can be adjusted by adding weights to the bottom. | ||

| Drift net |  |

The drift net is a net that is not anchored, but is drifting with the current. It is usually a gill or tangle net, and is commonly used in the coastal waters of many countries. Its use on the high seas is prohibited, but still occurs. | ||

| Drive-in net | A drive-in net is another fixed net, used by small-scale fishermen in some fisheries in Japan and South Asia, particularly in the Philippines. It is used to catch schooling forage fish such as fusiliers and other reef fish. It is a dustpan-shaped net, resembling a trawl net with long wings. The front part of the net is laid along the seabed. The fishermen either wait until a school swims into the net, or they drive fish into it by creating some sort of commotion. Then the net is closed by lifting the front end so the fish cannot escape.[19] | |||

| Fixed gillnet (on stakes) | .jpg.webp) |

Fixed gillnets[20] are nets for catching fish in shallow intertidal zones. It consists of a sheet of network stretched on stakes fixed into the ground, generally in rivers or where the sea ebbs and flows, for entangling and catching the fish. | ||

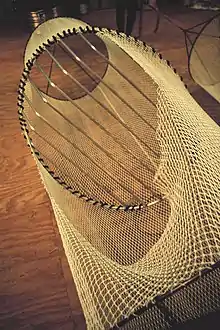

| Fyke net |  |

Fyke nets are bag-shaped nets which are held open by hoops. These can be linked together in long chains, and are used to catch eels in rivers. If fyke nets are equipped with wings and leaders, they can also be used in sheltered places in lakes where there is plenty of plant life. Hundreds of these nets can be connected into systems where it is not practical to build large traps.[21] It is similar to putcher fishing. | ||

| Gillnet | .jpg.webp) |

Sardines, salmon, cod | The gillnet catches fish which try to pass through it by snagging on the gill covers. Thus trapped, the fish can neither advance through the net nor retreat. Uses a system of nets with floats and weights. The nets are anchored to the sea floor and allowed to float at the surface | Animals cannot see the net, so they swim into it and are tangled. High risk of bycatch. |

| Ghost net | .jpg.webp) |

Ghost nets are nets that have been lost at sea. They may continue to be a menace to marine life for many years. | ||

| Haaf net |  |

Salmon | The haaf net is set in a rectangular wooden frame usually about four or five metres long and two metres wide supported by three legs. A central pole extends from one of the longer edges at a right angle. The fisherman wades into deep water and submerges the net, holding it upright with the central pole. When a fish swims into the net the fisherman tilts the pole backwards to scoop the net upwards, thereby trapping the fish.[22][23] | |

| Hand net |  |

Hand nets, also called scoop or dip nets, are held open by a hoop and may be attached to a short or a long stiff handle. They have been known since antiquity and can be used for sweeping up fish near the water surface like muskellunge and northern pike. When such a net is used by an angler to help land a fish, it is a landing net.[24] In England, hand netting is the only legal way of catching eels and has been practised for thousands of years on the Rivers Parrett and Severn. | ||

| Landing net |  |

Landing nets are large handheld nets that are used to lift caught fish out of the water, most commonly in angling and fly fishing. Landing nets are commonly used for large fish such as the common carp. | ||

| Lave net |  |

A special form of large hand net is the lave net, now used in very few locations on the River Severn in England and Wales. The lave net is set in the water and the fisherman waits till he feels a fish hit against the mesh and the net is then lifted. Fish as large as sturgeon are caught in lave nets.[25] | ||

| Lift net |  |

A lift net has an opening which faces upwards. The net is first submerged to a desired depth, and then lifted or hauled from the water. It can be lifted either manually (hand lift net) or mechanically (shore-operated lift net), and can be operated on a boat (boat-operated lift net)[26] | ||

| Midwater trawl | Pelagic fish such as anchovies, shrimp, tuna and mackerel | In midwater trawling a cone-shaped net is towed behind a single boat and spread by trawl doors (image), or it can be towed behind two boats (pair trawling) which act as the spreading device. | Midwater trawling is relatively benign compared to the damage bottom trawling can inflict on the sea bottom. | |

| Plankton net |  |

Plankton | Research vessels collect plankton from the ocean using fine mesh plankton nets. The vessels either tow the nets through the sea or pump sea water onboard and then pass it through the net.[27] | |

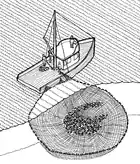

| Purse seine |  |

Schooling fish | The purse seine, widely used by commercial fishermen, is an evolution of the surround net, which in turn is an evolution of the seine net. A large net is used to surround fish, typically an entire fish school, on all sides. The bottom of the net is then closed by pulling a line arranged like a drawstring used to close the mouth of a purse. This completely traps the fish. | Higher chance of bycatch |

| Push net |  |

Shrimp | A push net is a "small triangular fishing net with a rigid frame that is pushed along the bottom in shallow waters and is used in parts of the southwestern Pacific for taking shrimps and small bottom-dwelling fishes".[28] | |

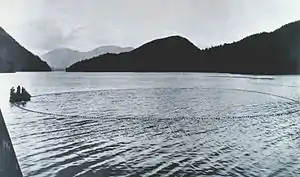

| Seine net |  |

A seine is a large fishing net that may be arranged in a number of different ways. In purse seine fishing the net hangs vertically in the water by attaching weights along the bottom edge and floats along the top. A simple and commonly used fishing technique is with beach seine, where the seine net is operated from the shore. Danish seine is a method which has some similarities with trawling. In the UK seine netting for Salmon and Sea-trout in coastal waters is only permitted in a very few locations and where it is permitted one end of the seine must remain fixed and the other end is then waded out and returns to the fixed point. This variant is called Wade netting and is strictly controlled by law.[29] | ||

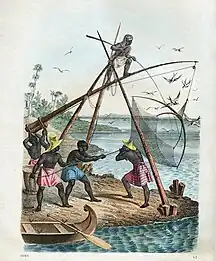

| Shore-operated lift net |  |

Pelagic species | These are held horizontally by a large fixed structure and periodically lowered into the water. Huge mechanical contrivances hold out horizontal nets with diameters of twenty metres or more. The nets are dipped into the water and raised again, but otherwise cannot be moved. The nets may hold bait or be fitted with lights to attract more fish.[30][31] The most famous examples are found at Kochi, India, where they are known as Chinese fishing nets (Cheena vala). Despite this name, this technique is used all over the world. They are also widely used on the Atlantic coast of France, where they are operated from small huts built over the water on stilts, known as carrelets, and on the Adriatic coast of Italy as trabucco. | |

| Surrounding net |  |

A surrounding net surrounds fish on all sides. It is an evolution of the seine, and is typically used by commercial fishers.[32] | ||

| Tangle net |  |

Tangle nets, also known as tooth nets, are similar to gillnets except they have a smaller mesh size designed to catch fish by the teeth or upper jaw bone instead of by the gills.[33] | ||

| Trammel | Demersal species, fish and crustaceans. | A trammel is a fishing net with three layers of netting that is used to entangle fish or crustacea.[34] A slack central layer with a small mesh is sandwiched between two taut outer layers with a much larger mesh. The net is kept vertical by the floats on the headrope and weights on the bottomrope. Floats can be small, cylindrical or egg-shaped, solid and plastic. They are attached on the head rope while weights made up of lead are distributed along the ground rope.[34] | Fisher can lose these net. This can result in "ghost fishing", with associated loss of marine animals continuing for the remaining life of the net. The net also capture of small sized organisms and non-target species. Such impact can be regulated by using larger meshes. However, compared to gillnets the selectivity of trammel nets are lower and catches of small organisms and non-target species are common. |

Fishing lines

Ropes and lines are made of fibre lengths, twisted or braided together to provide tensile strength. They are used for pulling, but not for pushing. The availability of reliable and durable ropes and lines has had many consequences for the development and utility of fishing nets, and influences particularly the scale at which the nets can be deployed.[35]

Floats

Some types of fishing nets, like seine and trammel, need to be kept hanging vertically in the water by means of floats at the top. Various light "corkwood"-type woods have been used around the world as fishing floats. Floats come in different sizes and shapes. These days they are often brightly coloured so they are easy to see.

- Small floats were usually made of cork, but fishermen in places where cork was not available used other materials, like birch bark in Sweden, Finland, and Russia, as well as the pneumatophores of mangrove apple in Southeast Asia.[36] These materials have now largely been replaced by plastic foam.

- Subsistence fishermen in some areas of Southeast Asia make corks for fishing nets by shaping the pneumatophores of mangrove apple into small floats.[36]

- Across the Indo-Pacific ocean, many Subsistence fishermen utilise discarded flip-flops as floats. This is especially common in the Western Indian Ocean on drag nets made from mosquito nets.[37]

- Entelea: The wood was used by Māori for the floats of fishing nets

- Native Hawaiians made fishing net floats from low density wiliwili wood.[38]

- Glass floats were large glass balls for long oceanic nets, now substituted by hard plastic. They are used not only to keep fishing nets afloat, but also for dropline and longline fishing. Often larger floats have marker flags for easier spotting.

- Glass floats are popular collectors' items. They were once used by fishermen in many parts of the world to keep fishing nets, as well as longlines or droplines afloat.

Finnish fishing net corks made out of birch bark and stones

Finnish fishing net corks made out of birch bark and stones Cork float of a fisher net engraved with a protective pentagram, Hvide Sande, Denmark

Cork float of a fisher net engraved with a protective pentagram, Hvide Sande, Denmark Dog conches are used to weigh down fishing nets.

Dog conches are used to weigh down fishing nets..jpg.webp) A plastic float being sewn onto a net

A plastic float being sewn onto a net

Weights and anchors

The Cucuteni–Trypillia culture, c. 5500 BC to 2750 BC in Eastern Europe, created ceramic weights in various shapes and sizes which were used as loom weights when weaving, and also were attached to fishing nets.[39]

Despite their ornamental value, dog conches are traditionally used by local fishermen as sinkers for their fishing nets.[40][41]

Production

.jpg.webp)

Fishing nets are usually manufactured on industrial looms, though traditional methods are still used where the nets are woven by hand and assembled in home or cottage industries.

Environmental impact

Fisheries often use large-scale nets that are indiscriminate and catch whatever comes along; sea turtle, dolphin, or shark. Bycatch is a large contributor to sea turtle deaths.[43] Longline, trawl,[44] and gillnet fishing are three types of fishing with the most sea turtle accidents. Deaths occur often because of drowning, where the sea turtle was ensnared and could not come up for air.[45] Cubs of endangered Saimaa ringed seal also drown to fishing nets.[46]

Fishing nets, usually made of plastic, can be left or lost in the ocean by fishermen. Known as ghost nets, these entangle fish, whales, dolphins, sea turtles, sharks, dugongs, crocodiles, seabirds, crabs, and other creatures, restricting movement, causing starvation, laceration and infection, and, in those that need to return to the surface to breathe, suffocation.[47]

A turtle excluder device (TED)

A turtle excluder device (TED) Sea turtle entangled in a net

Sea turtle entangled in a net Loggerhead sea turtle exiting from fishing net through a turtle excluder device

Loggerhead sea turtle exiting from fishing net through a turtle excluder device

Miscellany

Divers may become trapped in fishing nets; monofilament is almost invisible underwater. Divers often carry a net cutter. This is a small handheld tool carried by scuba divers to extricate themselves if trapped by a fishing net or fishing line. It has a small sharp blade such as a replaceable scalpel blade inside the small notch. There is a small hole at the other end to for a lanyard to tether the cutter to the diver.

Gallery

| Fishing nets round the world |

|---|

Three fykes at the Zuiderzeemuseum, Netherlands  Fishermen in Bangladesh  Moroccan fisherman mending his nets  Fishing nets on pontoons .jpg.webp) Fishing nets on a shrimp boat, Ostend, Belgium  Fishing with a cast net  Fishing nets and marker flags used on a small fishing vessel at Lyme Regis, England  Net manufacturer Larrieu Frères in Bordeaux, France, founded 1622 |

Notes

- Miettinen, Arto; Sarmaja-Korjonen, Kaarina; Sonninen, Eloni; Junger, Högne; Lempiäinen, Terttu; Ylikoski, Kirsi; Mäkiaho, Jari-Pekka; Carpelan, Christian; Jungner, Högne (2008). "The palaeoenvironment of the Antrea Net Find". Karelian Isthmus. Finnish Antiquarian Society: 71–87. ISBN 9789519057682.

- "Cast from the past: World's oldest fishing net sinkers found in South Korea". m.phys.org.

- Kriiska, Aivar (1996) "Stone age settlements in the lower reaches of the Narva River, north-eastern Estonia" Coastal Estonia: Recent Advances in Environmental and Cultural History. PACT 51. Rixensart. Pages 359–369.

- Indreko R (1932) "Kiviaja võrgujäänuste leid Narvas" (Stone Age find of fishing net remnants), in Eesti Rahva Muuseumi Aastaraamat VII, Tartu, pp. 48–67 (in Estonian).

- Smith, Courtland L Seine fishing Oregon Encyclopedia. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- Meredith, Paul "Te hī ika – Māori fishing" Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2 March 2009.

- Radcliffe W (1926) Fishing from the Earliest Times John Murray, London.

- Johnson WM and Lavigne DM (1999) Monk Seals in Antiquity Fisheries, pp. 48–54. Netherlands Commission for International Nature Protection.

- Gilroy, Clinton G (1845) "The history of silk, cotton, linen, wool, and other fibrous substances: including observations on spinning, dyeing and weaving" pp. 455–464. Harper & Brothers, Harvard University.

- Image of fishing illustrated in a Roman mosaic Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- Auguet, Roland [1970] (1994). Cruelty and Civilization: The Roman Games. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10452-1.

- Luke 5:4-6; John 21:3-7a

- Werthner, William B. (1935). Some American Trees: An intimate study of native Ohio trees. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. xviii + 398 pp.

- Bilton, Kathy. "Pawpaws: A paw for you and a paw for me". Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- J.C. Turner and P. van de Griend (ed.), The History and Science of Knots (Singapore: World Scientific, 1996), 14.

- Martinussen, Atle Ove (2006) "Nylon Fever: Technological Innovation, Diffusion and Control in Norwegian Fishery during the 1950s" MAST, 5(1): 29–44.

- "Australia State of the Environment Report 2001 - Coasts and Oceans Theme Report: Fisheries (Impacts of wild fish harvesting activity)". Archived from the original on 2006-09-09. Retrieved 2012-05-12.

- Casting net Archived 2021-02-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gabriel, Otto; Andres von Brandt (2005). Fish Catching Methods of the World. Blackwell. ISBN 0-85238-280-4.

- FAO, Fishing Gear Types : Fixed Gillnets (on stakes), Fisheries and Aquaculture Department, 2011

- fyke net (2008) In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 24, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Scott, Allen J. (2014). Solway Country: Land, Life and Livelihood in the Western Border Region of England and Scotland. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1-4438-7140-2.

- Peters, Jonathan (21 January 2020). "Fight to save 1,000-year-old fishing technique". BBC News. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Fishing Tools - Landing Nets Archived 2008-09-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lave Net Fishing". severnsideforum.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2010-03-25. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- FAO, Lift net Fishing Gear Types. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- Ichthyoplankton sampling methods Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA. Modified 3 September 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Commission of the European Communities, Multilingual dictionary of fishing gear Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine, 2nd edition, 1992 (n° 3247 p.[183]205).

- studio, TalkTalk web. "TalkTalk Webspace is closing soon!!". web.onetel.net.uk.

- Commission of the European Communities, Multilingual dictionary of fishing gear Archived 2016-04-30 at the Wayback Machine, 2nd edition, 1992 (n° 3062 p.[56]78).

- "FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture - Fishing gear type". www.fao.org.

- "MONOGRAPH". map.seafdec.org.

- Selective Fishing Methods Archived 2018-02-14 at the Wayback Machine Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Fishing Gear Types: Trammel nets", Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, retrieved 2010-09-27

- Hansen, Viveka (6 October 2022) Fishing nets and lines, IK Foundation.

- Wild Singapore - Berembang Sonneratia caseolaris

- Jones, Benjamin L.; Unsworth, Richard K. F. (2019-11-11). "The perverse fisheries consequences of mosquito net malaria prophylaxis in East Africa". Ambio. 49 (7): 1257–1267. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01280-0. ISSN 1654-7209. PMC 7190679. PMID 31709492.

- "Erythrina sandwicensis (Fabaceae)". Meet the Plants. National Tropical Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- Prehistoric textiles: the development of cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze By E.J.W. Barber

- Poutiers, J. M. (1998). "Gastropods" (PDF). In Carpenter, K. E. (ed.). The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). p. 471. ISBN 92-5-104051-6.

- Purchon, R. D. & Purchon D. E. A. (1981). "The marine shelled Mollusca of West Malaysia and Singapore. Part I. General introduction and account of the collecting stations". Journal of Molluscan Studies 47: 290–312.

- "Fishing nets for a future: helping Syrian women in Lebanon". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2015-04-08.

- Stokstad, Erik. "Sea Turtles Suffer Collateral Damage From Fishing." Science AAAS 07 Apr 2010: n. pag. Web. 8 Dec 2010."Sea Turtles Suffer Collateral Damage from Fishing - ScienceNOW". Archived from the original on 2012-03-10. Retrieved 2012-05-12.

- Sasso, Christopher, and Sheryan Epperly. "Seasonal sea turtle mortality risk from forced submergence in bottom trawls." Fisheries Research 81.1 (2006): 86-88. Web. 15 Dec 2010.

- Haas, Heather, Erin LaCasella, Robin LeRoux, Henry Miliken, and Brett Hayward. "Characteristics of sea turtles incidentally captured in the U.S. Atlantic sea scallop dredge fishery." Fisheries Research 93.3 (2008): 289-295. Web. 15 Dec 2010.

- "Finnish conservationists worry about Saimaa ringed seal as fishing net ban ends". Eye On The Arctic. July 2020.

- "'Ghost fishing' killing seabirds". BBC News. 28 June 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

References

- Fridman AL and Carrothers PJG (1986) Calculations for fishing gear designs" (FAO fishing manual), Fishing News Books. ISBN 978-0-85238-141-0

- Klust, Gerhard (1982) Netting materials for fishing gear FAO Fishing Manuals, Fishing News Books. ISBN 978-0-85238-118-2. Download PHP (9MB)

- Prado J and Dremière PY (eds.) (1990) Fisherman's workbook FAO, Rome. ISBN 0-85238-163-8.

- von Brandt A (1984) Fish catching methods of the world Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-85238-280-6.