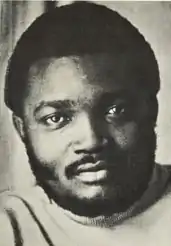

Franco Luambo

François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi (6 July 1938 – 12 October 1989) was a Congolese musician. He was a major figure in 20th-century Congolese music, and African music in general, principally as the leader for over 30 years of TPOK Jazz, the most popular and significant African band of its time. He is referred to as Franco Luambo or simply Franco. Known for his mastery of African Rumba, he was nicknamed by fans and critics "Sorcerer of the Guitar" and the "Grand Maître of Zairean Music", as well as Franco de Mi Amor by female fans.[1] His most known hit, "Mario", sold more than 200,000 copies and was certified gold.[2]

Franco Luambo | |

|---|---|

Luambo Makiadi In the early 1970s | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | François Luambo Luanzo Makiadi |

| Also known as | Franco |

| Born | 6 July 1938 Sona Bata, Belgian Congo (modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo) |

| Origin | |

| Died | 12 October 1989 (aged 51) Mont-Godinne, Province of Namur, Belgium |

| Genres | African rumba, soukous |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) | Guitar vocals |

| Years active | 1950s–1980s |

| Labels | |

Early life

Born 6 July 1938 in his mother's hometown of Sona-Bata in what was then the Belgian Congo, he grew up in the capital city, Léopoldville (now Kinshasa). When his father, a railroad worker, died in 1949, he ended his formal education at age 10 or 11 and helped his mother by playing a homemade guitar, harmonica and other instruments to attract customers to her market stall in Léopoldville's Ngiri-Ngiri neighborhood. He also honed his guitar-playing by working with Paul "Dewayon" Ebengo, a slightly older friend who had a real guitar.[3][4]

In 1950, Franco (then age 12), Dewayon (age 16), and others formed a group called Watam, which played together for three years, playing weddings and funerals and with the help of a mentor of Franco's, the established musician Albert Luampasi, recording a few songs on the Ngoma record label.[5]: 53

Career

In 1953, Franco and Dewayon auditioned for musician and producer Henri Bowane, then with Leopoldville's Loningisa record label and studio, who hired both as studio musicians.[5]: 54 Franco released at least three records in 1953 with Watam on Loningisa, on which he was credited as Lwambo François.[6] Also in 1953, Franco released on Loningisa his first solo record, "Bolingo Na Ngai Na Beatrice" (my love for Beatrice), which made Franco a local celebrity in Kinshasa.[5]: 55 [7]: 188 Bowane is also said to have given the young musician his lifelong name, Franco.[5]: 52

In 1955, Franco was among a loose group of Leopoldville musicians that began working together under the auspices of the Loningisa studio; the group was known as Bana Loningisa (children of Loningisa). In 1956, an original founding core of six of those musicians, with Franco as the sole guitarist, agreed to accept a regular, paid gig at the O.K. Bar, named after its owner, Oskar Kashama. A few weeks later, needing a name for a contract, the band used OK Jazz, from the place it had begun (it has also been said that O.K. stood for Orchestre Kinois, or the band of Kinshasa), and they were "baptized" under that name at a June 6, 1956 show at the O.K. Bar. While clarinetist Jean Serge Essous was the original leader of O.K. Jazz, Franco was a prolific songwriter; Essous called him a "kind of genius" for having written over a hundred songs in his notebooks at that time. O.K. Jazz quickly became a rival to the leading established local band of that time, African Jazz under Joseph Kabasele. In December 1956, after some personnel changes, the new (and short-lived) lineup of O.K. Jazz released a rumba written by Franco' that would become the band's motto: "On Entre O.K., On Sort K.O."[5]: 56–59 [8]

In 1957, O.K. Jazz lost its leader, Essous, as well as original vocalist Philippe "Rossignol" Lando, when they were hired away by Bowane for his new record label, Esengo (Bowane had left Loningisa after being outshone there by O.K. Jazz).[5]: 64–65 While vocalist Vicky Longomba became the band's new leader, Franco also stepped up.

In 1958, after O.K. Jazz returned to Leopoldville after a year in Brazzaville, Franco was arrested and jailed for a "motoring offence."[7]: 188 Upon his release, he regained and reinforced his local reputation as the "Sorcerer of the Guitar."[7]: 188 His guitar technique was so influential that by the end of the 1950s and for years afterward, Congolese guitarists were divided into two camps, one led by Franco and the other led by Docteur Nico of Joseph Kabasele's African Jazz.[7]: 188

Through the 1960s, Franco and O.K. Jazz "toured regularly and recorded prolifically."[7]: 188 By 1967 Franco was a co-leader of the band, with vocalist Vicky.[4] When Vicky left in 1970, Franco became the sole leader of the band.[4]

And then, another change to Tout Puissant O.K. Jazz (T.P.O.K. Jazz) (which stands in French for The Almighty O.K. Jazz)

In 1978, Franco was imprisoned for two months by Zaire's President Mobutu for the lyrics to his songs "Helene" and "Jackie."[7]: 189 Later the same year, however, President Mobutu decorated him for his musical contributions.[7]: 189

Luambo recorded a 21-minute track, “Na Lingaka Yo Yo Te”. It is the longest song recorded by a Congolese artist.

Franco played in the United States once, in 1983,[9] appearing twice in New York's Manhattan Center.[1]

In his thirty-three years with the band, Franco and TPOK Jazz released hundreds of singles and over 100 albums.[7]: 188

Politics

Luambo was a vocal supporter of Zaire's ruler Mobutu Sese Seko. However, they soon became enemies.[1]

Death

Franco died on 12 October 1989,[10] at Namur in Belgium, of AIDS. (He never publicly acknowledged having AIDS, and while many sources flatly report it as the cause of death, others report this as unconfirmed, e.g., The New Yorker uses "of an illness believed to be AIDS.") Upon his death, President Mobutu declared four days of national mourning in Zaire.[8][11][12][13][14]

Recorded output

It is difficult to summarize the enormous volume of recordings issued by Franco (virtually all of them with TPOK Jazz), and work remains to be done in this area. The range of estimates suggest both the size of, and the uncertainties about, his output. An often-cited number is that Graeme Ewens listed eighty-four albums in the thoroughly researched discography (based on the work of Ronnie Graham) in Ewens' 1994 biography of Franco; this list does not include compilation albums that also have other performers, or O.K. Jazz tribute albums and compilations issued after Franco's death (Ewens noted about this number that "it falls short of the 150 albums which Franco claimed back in the mid-1980s, but no doubt some of those were collections of singles for the African market"). Ten albums on the list were issued in 1983 alone.[15] Other statements include: "he released roughly 150 albums and three thousand songs, of which Franco himself wrote about one thousand;"[16] "Franco’s prolific output amounted to T.P.O.K releasing two songs a week over his nearly 40-year career, which ultimately comprised a catalogue of some 1000 songs;"[17] "With his band OK Jazz he released at least 400 singles (more than half later compiled onto LP or CD) . . . . Ewens list 36 CDs; Asahi-net has 83;"[18] and "from June 1956 to August 1961 the band recorded 320 tracks for the 78 rpm music label Loningisa."[19]

As a rough explanation of its nature, in the 1950s and 1960s Franco and TPOK Jazz issued singles, either 78rpm (1950s) or 45rpm (1960s), as well as some albums that were compilations of singles, and in the 1970s and 1980s they issued longer albums. All of this was done by a large number of record labels, in a variety of countries in Africa and Europe as well as the United States. In the 1990s, many of the albums were reissued in CD form by various record labels but haphazardly reorganized, often combining various parts of multiple albums onto single CDs. Since 2000, several compilations have been issued collecting aspects of Franco's work, most notably Francophonic, a pair of two-CD sets of highlights issued by Stern's in 2007 and 2009 and spanning Franco's entire career. Through 2020, the Planet Ilunga record label is still able to issue (on vinyl and digitally) compilations that include tracks which had never been reissued since their original release as singles.[20]

Musical style, critical evaluations, and significance

Franco's guitar playing was unlike that of bluesmen such as Muddy Waters or rock and rollers like Chuck Berry. Instead of raw, single-note lines, Franco built his band's style around crisp open chords, often of only two notes, which "bounced around the beat." Major thirds and sixths and other consonant intervals are said to play the same role in Franco's style that blues notes fill in rock and roll.[21]

Franco's music often relied on huge ensembles, with as many as six vocalists and several guitarists. According to a description, "horns might engage in an upbeat dialogue with the guitar, or set up hypnotic vamps that carried the song forward as on the crest of a wave," while percussion parts are "a cushion supporting the band, rather than a prod to raise the energy level."[21]

Franco was a member for 33 years, from its founding in 1956 until his death in 1989, of TPOK Jazz, which has been called "arguably the most influential African band of the second half of the 20th century,"[22] and he was its co-leader or sole leader for most of that period.

Franco is commonly described as the preeminent African musical figure of the 20th century. For example, world-music expert Alistair Johnston calls him "the giant of 20th century African music."[23] A reviewer in The Guardian wrote that Franco "was widely recognised as the continent's greatest musician, back in the years before Ali Farka Touré or Toumani Diabaté."[24] Ronnie Graham wrote, in his encyclopedic 1988 Da Capo Guide to Contemporary African Music, that "Franco is beyond doubt Africa's most popular and influential musician."[7]: 188 This is in addition to listing Franco first in his book's rank-ordered section on Congo and Zaire, and putting on the book's cover, to represent African music, a waist-up photo of Franco playing guitar.

Personal life

Franco was married twice.[4] He reportedly fathered eighteen children (seventeen of them girls) with fourteen women.[1]

Selected discography

This is a very preliminary, partial list.

| Year | Album |

|---|---|

| 1969 | Franco & Orchestre O.K. Jazz* – L'Afrique Danse No. 6 (LP) |

| 1973 | Franco & OK Jazz* – Franco & L'O.K. Jazz |

| 1974 | Franco Et L'Orchestre T.P.O.K. Jazz* – Untitled |

| 1977 | "Franco" Luambo Makiadi* And His O.K. Jazz* – Live Recording of the Afro European Tour Volume 2 (LP, album) |

| 1977 | "Franco" Luambo Makiadi* & His O.K Jazz* – Live Recording of the Afro European Tour |

| 1981 | Soki Odefi Zongisa (LP, album) |

| 1982 | Franco Et Sam Mangwana Avec Le T.P. O.K. Jazz* – Franco Et Sam Mangwana Avec Le T.P.O.K. Jazz (LP) |

| 1983 | Franco & Tabu Ley* – Choc Choc Choc 1983 De Bruxelles A Paris |

| 1986 | Franco & Le T.P.O.K. Jazz – Choc Choc Choc La Vie Des Hommes – Ida – Celio (30 Ans De Carrière – 6 Juin 1956 – 6 Juin 1986) (LP) |

| 1987 | Franco Et Le T.P.O.K. Jazz – L'Animation Non Stop (LP) |

| 1988 | Le Grand Maitre Franco* - Baniel - Nana et le T.P.O.K. Jazz* - Les "On Dit" (LP) |

| 1989 | Franco Et Sam Mangwana – For Ever (LP, Cass) |

Compilation albums:

| Year | Album |

|---|---|

| 1993 | Franco & son T.P.O.K. Jazz – 3eme Anniversaire de la Mort du Grand Maitre Yorgho (CD) |

| 2001 | Franco – The Rough Guide To Franco: Africa's Legendary Guitar Maestro (CD) |

| 2007 | Franco & le T.P.O.K. Jazz – Francophonic: A Retrospective Vol. 1 1953-1980 (2 CDs) |

| 2009 | Franco & le T.P.O.K. Jazz – Francophonic: A Retrospective, Vol. 2: 1980-1989 (2 CDs) |

| 2017 | O.K. Jazz – The Loningisa Years 1956-1961 (2 records, and digital) |

| 2020 | Franco & l'Orchestre O.K. Jazz – La Rumba de mi Vida (2 records, and digital) |

| 2020 | O.K. Jazz – Pas Un Pas Sans… The Boleros of O.K. Jazz 1957-77 (2 records, and digital) |

See also

References

- Christgau, Robert (3 July 2001). "Franco de Mi Amor". Village Voice. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Stewart, Gary (2003). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-85984-368-0.

- Al Angeloro (March 2005). "World Music Legends: Franco". Global Rhythm. Zenbu Media. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Stewart, Gary. "Franco (Luambo Makiadi, François)". Rumba on the River: Web home of the book. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Stewart, Gary (2000). Rumba on the river : a history of the popular music of the two Congos. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-744-7.

- "Watam". Discogs. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Graham, Ronnie (1988). The Da Capo guide to contemporary African music. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80325-9.

- Nickson, Chris (2006). "Franco: artist biography". All Music. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Giola, Ted. "The James Brown of Africa (Part One)". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Uwechue, Raph (1991). Makers of Modern Africa (Second ed.). United Kingdom: Africa Books Limited. pp. 237–238. ISBN 0903274183.

- Niarchos, Nicolas (25 June 2019). "The Death of Simaro Lutumba Closes a Chapter of Congolese Music". The New Yorker. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African Magazine. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Schnabel, Tom (4 August 2020). "Spotlight on Congolese Superstar Franco". KCRW. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Njiiri, Kari. "Jazz Safari features Congo's Music Legend Franco and His Challenge to Society: Beware of AIDS". New England Public Radio. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Ewens, Graeme (4 January 1994). "Discography". Congo Colossus: The Life and Legacy of Franco & OK Jazz. Buku Press. 270-306 320 pages. ISBN 978-0952365518.

- "Franco & le TPOK Jazz – 'Francophonic'". Brave New World (blog). 20 May 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "The Return of the Rumba. "Franco, The Sorcerer of the Guitar"". Afro-Sonic Mapping. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Johnston, Alistair. "Congo part 3". muzikifan. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "O.K. Jazz - The Loningisa Years 1956-1961 2xLP". Aguirre Records. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- "New release: Franco & l'orchestre O.K. Jazz – La Rumba de mi Vida". Planet Ilunga. 21 January 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- Giola, Ted. "The James Brown of Africa (Part Two)". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- Lusk, Jon (22 September 2007). "Madilu System (obituary)". The Independent. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- Johnston, Alastair. "Congo part 1". Muzikifan.

- Denselow, Robin (14 November 2008). "CD: Franco & Le TPOK Jazz, Francophonic Vol. 1". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

Further reading

External links

- Discography of Franco & OK Jazz

- A fan page for Franco and OK Jazz describing events decade by decade

- 1983 Interview with Franco

- Liner notes from Franco phonic – Vol. 1: 1953–1980 Archived 19 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine by Ken Braun / Sterns Music Archived 17 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine