Congolese rumba

Congolese rumba, also known as African rumba, is a dance music genre originating from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) and the Republic of the Congo (formerly French Congo). With its rhythms, melodies, and lyrics, Congolese rumba has gained global recognition and remains an integral part of African music heritage. In December 2021, it was added to the UNESCO list of intangible cultural heritage.[1][2][3]

| Congolese rumba | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Late 1930s in the Congos (esp. Kinshasa and Brazzaville) |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Derivative forms | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Other topics | |

| Music of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| Congolese rumba | |

|---|---|

Bakolo Music International, the oldest traditional Congolese rumba music group, during a rehearsal in 2014 | |

| Country | Democratic Republic of the Congo and Republic of the Congo |

| Reference | 01711 |

| Region | Central Africa |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2021 |

Emerging in the mid-20th century in the urban centers of Kinshasa and Brazzaville during the colonial era, Congolese rumba originated from a fusion of various musical influences, including traditional Kongolese rhythms and Cuban rumba.[4][5] Congolese rumba customarily features lively guitar melodies, groovy basslines, catchy rhythms, and danceable beats.[6] The genre's roots can be traced to the 1930s, when African musicians, particularly those from the Congo Basin, incorporated guitar, bottles, and ikembe to perform songs in traditional forms combined with Cuban rumba and son.[7][8][9][10][11] This gave rise to soukous, a genre characterized by its lively rhythms, intricate high-pitched guitar melodies, and large brass and polyrhythmic percussion sections.[12]

The style has gained widespread popularity in Africa, reaching countries like Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Zimbabwe, Madagascar, Zambia, Ivory Coast, Gambia, Nigeria, Ghana, South Sudan, Senegal, Burundi, Malawi, and Namibia. Additionally, it has found a following in Europe, particularly in France, Belgium, Germany, and the UK, as well as the US, as a result of touring by Congolese musicians, who have performed at various festivals internationally. Musicians such as Henri Bowane, Wendo Kolosoy, Franco Luambo Makiadi, Le Grand Kallé, Nico Kasanda, Tabu Ley Rochereau, Sam Mangwana, Papa Noel Nedule, Vicky Longomba, and Papa Wemba have made significant contributions to the genre, pushing its boundaries and incorporating modern musical elements.[13][14][1]

History

Origins

A proposed etymology for the term "rumba" is that it derives from the Kikongo word nkumba, meaning "belly button", denoting the native dance practiced within the former Kingdom of Congo, encompassing parts of the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo, Republic of the Congo, and Angola.[15][16][17] Its rhythmic foundation draws from Bantu traditions, notably the Palo Kongo religion, which traces back to the Kongo people who were unceremoniously transported to Cuba by Spanish settlers in the 16th century.[4][18][19][20] According to Miguel Ángel Barnet Lanza's On Congo Cults of Bantu Origin in Cuba, the majority of African slaves brought to Cuba were of Bantu origin, although later, the Yoruba from Nigeria became the primary group of slaves in Cuba.[21] Despite the tribulations endured by enslaved Africans, their musical traditions, dance forms, and spiritual practices from were covertly preserved across generations within regions characterized by significant populations of enslaved Africans.[10] Musical instruments like the conga, makuta, catá, yambu, claves, güiro, and cajón de rumba were used to craft a musical dialogue that engaged in call-and-response with ancestral spirits and the deceased.[22][4] Notable figures like Arsenio Rodríguez blended traditional Bakongo sounds with Cuban son.[20]

Late 1930s–1950s

In the 1930s and 1940s, the music of Cuban son groups, such as Septeto Habanero, Trio Matamoros, and Los Guaracheros de Oriente, was played on Radio Congo Belge in Léopoldville, gaining popularity in the country during the following decades.[23][24] Once local bands tried to emulate this sound—referred to as "rumba" in Africa, although it is unrelated to Cuban rumba)—their music became known as "soukous", a derivative of the French word "secouer" (literally, "to shake").[25] By the late 1960s, soukous was an established genre in most of Central Africa, and it would also impact the music of West and East Africa.[26][27][13]

Congolese bands started doing Cuban covers, singing the Spanish lyrics phonetically. Eventually, they created original compositions with lyrics in French or Lingala, a lingua franca of the western Congo region, and adapted Cuban guajeos to guitars.[28] Antoine Kolosoy, also known as Papa Wendo, became the first star of African rumba, touring Europe and North America in the 1940s and 1950s with his regular band, Victoria Bakolo Miziki, or Victoria Kin.[29] Kolosoy was inspired by Paul Kamba's band, Victoria Brazza. Before Kamba, a Martinican man named Jean Réal had formed the band Congo Rumba in Brazzaville.[30][31]

By the 1950s, big bands had become the preferred format, using acoustic bass guitars, multiple electric guitars, conga drums, maracas, scrapers, flutes, or clarinets, saxophones, and trumpets. Grand Kalle et l'African Jazz (also known as African Jazz), led by Joseph Kabasele Tshamala, and OK Jazz, later renamed TPOK Jazz, led by Franco Luambo, became the leading bands. One of the musical innovations of Franco's band was the mi-solo (meaning "half solo") guitarist, playing arpeggio patterns and filling a role between the lead and rhythm guitars.[32]

1960s–1970s

In the 1950s and 1960s, some artists who had performed in the bands of Franco Luambo and Grand Kalle formed their own groups. Tabu Ley Rochereau and Nico Kasanda created African Fiesta and transformed their music further by fusing Congolese folk with soul, as well as Caribbean and Latin beats and instrumentation. They were joined by Papa Wemba and Sam Mangwana, and classics like "Afrika Mokili Mobimba" made them one of Africa's most prominent bands.[33][34][35] Other greats of this period include Koffi Olomide, Tshala Muana, and Wenge Musica.

While the rumba influenced bands such as Lipua-Lipua, Veve, TPOK Jazz, and Bella Bella, younger Congolese musicians looked for ways to reduce that influence and play a faster-paced soukous.[36] A group of students called Zaiko Langa Langa came together in 1969 around founding vocalist Papa Wemba.[37] Pepe Kalle, a protégé of Grand Kalle, created the band Empire Bakuba together with Papy Tex, and they too became popular.

East Africa in the 1970s

Soukous now spread across Africa and became an influence on virtually all the styles of modern African popular music, including highlife, palm-wine music, taarab, and makossa. As political conditions in Zaire, as the Democratic Republic of the Congo was then known, deteriorated in the 1970s, some groups made their way to Tanzania and Kenya.[13] By the mid-1970s, several Congolese groups were playing soukous at Kenyan nightclubs.[38] The lively cavacha, a dance craze that swept East and Central Africa during the 1970s, was popularized through recordings of bands such as Zaïko Langa Langa and Orchestra Shama Shama, influencing Kenyan musicians.[39] This rhythm, played on the snare drum or hi-hat, briskly became a hallmark of the Congolese sound in Nairobi and was frequently used by regional bands. Several of Nairobi's renowned Swahili rumba bands formed around Tanzanian groups like Simba Wanyika and their offshoots, Les Wanyika and Super Wanyika Stars.[40][39][38]

In the late 1970s, Virgin Records produced albums from the Tanzanian–Congolese Orchestra Makassy and the Kenya-based Super Mazembe, with the Swahili song "Shauri Yako" becoming a hit in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Les Mangelepa was another influential Congolese group that moved to Kenya and became popular throughout East Africa. Around this same time, the Nairobi-based Congolese vocalist Samba Mapangala and his band, Orchestra Virunga, issued the album Malako, which became one of the pioneering releases of the newly emerging world music scene in Europe. The musical style of the East Africa-based Congolese bands gradually incorporated new elements, including Kenyan benga music, and spawned what is sometimes called the "Swahili sound" or "Congolese sound".[41][42][43]

21st century

In December 2021, Congolese rumba was added to the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[44][45]

Congolese rumba is a musical genre and a dance used in formal and informal spaces for celebration and mourning. It is primarily an urban practice danced by a male-female couple. Performed by professional and amateur artists, the practice is passed down to younger generations through neighbourhood clubs, formal training schools and community organisations. The rumba is considered an integral part of Congolese identity and a means of promoting intergenerational cohesion and solidarity.

— UNESCO, news release

Musical examples

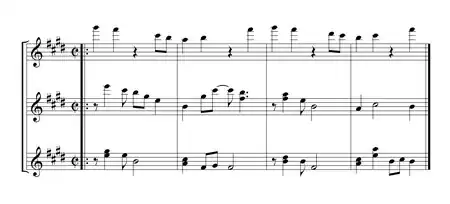

The following example is from the Congolese rumba "Passi ya boloko" by Franco (Luambo Makiadi) and O.K. Jazz (c. mid-1950s).[46] The bass is playing a tresillo-based tumbao, typical of son montuno. The rhythm guitar plays all of the offbeats, the exact pattern of the rhythm guitar in Cuban son. According to the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, the lead guitar part "recalls the blue-tinged guitar solos heard in bluegrass and rockabilly music of the 1950s, with its characteristic insistence on the opposition of the major-third and minor-third degrees of the scale."[47]

Banning Eyre distills down the Congolese guitar style to this skeletal figure, where the guide-pattern clave is sounded by the bass notes (notated with downward stems).[48]

In a densely textured seben section of a soukous song (below), the three interlocking guitar parts are reminiscent of the contrapuntal structure of Cuban music, with its layered guajeos.[49]

Influence

Colombian champeta

African music has been popular in Colombia since the 1970s and has had a significant impact on the local musical genre known as champeta.[50][51] In the mid-1970s, a group of sailors introduced records from the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria to Colombia, including a plate-numbered 45 RPM titled El Mambote by Congo's l'Orchestre Veve, which gained popularity when played by DJ Victor Conde.[52][53][54][55] Record labels proactively dispatched producers to find African records that would resonate with DJs and audiences. The music gained traction, especially in economically underprivileged urban areas, predominantly inhabited by Afro-Colombian communities, where it was incorporated into sound systems at parties across cities such as Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Palenque de San Basilio.[52]

The emergence of champeta involved replicating musical arrangements by Congolese artists like Nicolas Kasanda wa Mikalay, Tabu Ley Rochereau, M'bilia Bel, Syran Mbenza, Lokassa Ya M'Bongo, Pépé Kallé, Rémy Sahlomon, and Kanda Bongo Man.[54][53] Local artists such as Viviano Torres, Luis Towers, and Charles King, all from Palenque de San Basilio, started composing their own songs and producing unique musical arrangements, while still maintaining the Congolese soukous influence, a derivative of Congolese rumba.[52] They composed and sang in their native language, Palenquero, a creole mix of Spanish and Bantu languages like Kikongo and Lingala.[52][56]

Champeta's sound is intimately intertwined with Congolese rumba, particularly the soukous style, sharing the same rhythmic foundation. The guitar and the use of the Casio brand synthesizer for sound effects are instrumental in shaping champeta's distinct sound.[55]

During the Super Bowl LIV halftime show on 2 February 2020, at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Florida, Shakira danced to the song "Icha" by the Congolese artist Syran Mbenza, accompanied by several dancers. The track is colloquially known as "El Sebastián" in Colombia. Shakira's performance inspired the #ChampetaChallenge on various social media platforms.[55][57]

Ivorian coupé-décalé

The Congolese rumba dance called ndombolo has significantly impacted coupé-décalé dance music with the incorporation of atalaku, a term referencing animators or hype men who enhance the rhythm and interactivity of performances, into its songs.[58][59][60][61] The first Congolese band to employ atalaku was Zaïko Langa Langa, in the 1980s. In one of their early compositions featuring these animators, the repeated chant "Atalaku! Tala! Atalaku mama, Zekete" (Look at me! Look! Look at me, mama! Zekete!) echoed, commanding attention.[62][63] As coupé-décalé emerged, the Congolese rumba influence remained conspicuous. Notably, with the release of "Sagacité", Douk Saga's debut hit, the explicit imprint of atalaku was apparent.[58] In an RFI interview, DJ Arafat, an Ivorian musician, acknowledged atalaku's influence on his artistic approach. The term has transcended its origins, becoming embedded in the lexicon of Ivory Coast and neighboring countries, though it now signifies "flattery".[55][64]

French hip hop

With the emergence of satellite television across Africa in the early 1990s, coupled with the subsequent development and expansion of the internet across the continent in the subsequent decades, French hip hop flourished within the African francophone market.[65][66][67] Originating in the United States, the genre rapidly gained popularity among youth of African descent in France and various other European nations.[65][68][69] Initially molded by American hip hop, the French variant has since developed a distinct identity and sound, drawing influences from the African musical heritage shared by many French rappers.[65]

By the late 1990s, Bisso Na Bisso, a collective of French rappers from the Republic of the Congo, pioneered the infusion of Congolese rumba rhythms into French rap.[70][71][72] Their album Racines melds hip hop, Congolese rumba, soukous, and zouk rhythms, featuring collaborations with African artists like Koffi Olomidé, Papa Wemba, Ismaël Lô, Lokua Kanza, and Manu Dibango, alongside the French-Caribbean zouk group Kassav'.[73] Nearly all their thematic elements revolve around a reconnection with their roots, evident through samples sourced directly from Congolese rumba and soukous.[70][73] In the early 2000s, the lingua franca of many French rap tracks was Lingala, accompanied by resonant rumba guitar riffs.[74][75] Mokobé Traoré, a Malian–French rapper, further accentuated this influence on the album Mon Afrique, where he featured artists like Fally Ipupa on the soukous-inspired track "Malembe".[73] The far-reaching impact of "Congolization" transcends hip hop, permeating other genres like French R&B and religious music, all while concurrently gaining traction across Europe and francophone Africa.[55] Prominent artists include Youssoupha, Maître Gims, Dadju, Niska, Singuila, Damso, KeBlack, Naza, Zola, Kalash Criminel, Ninho, Kaysha, Franglish, Gradur, Shay, Bramsito, Baloji, Tiakola, and Ya Levis Dalwear—all descendants of Congolese musical lineage.[74][75][76][77]

See also

References

- Stewart, Gary (5 May 2020). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. ISBN 9781789609110.

- Pietromarchi, Virginia (15 December 2021). "'The soul of the Congolese': Rumba added to UNESCO heritage list". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "43 elements inscribed on UNESCO's inscribed on UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage lists". UNESCO. 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021.

- Jelly-Schapiro, Joshua (22 November 2016). Island People: The Caribbean and the World. New York City, New York State, United States: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780385349772.

- "Beneath the rhythm, Congolese rumba is a link to the past". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- "Congolese rumba: why the dance recognised by Unesco is special". South China Morning Post. 16 December 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- Davies, Carole Boyce (29 July 2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture [3 volumes]. Santa Barbara, California: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 848–849. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- Erenberg, Lewis A. (14 September 2021). The Rumble in the Jungle: Muhammad Ali and George Foreman on the Global Stage. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780226792347.

- Mongrue, Jesse (10 June 2016). What's Working in Africa?: Examining the Role of Civil Society, Good Governance, and Democratic Reform. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse. ISBN 9781491795019.

- Silusawa, Lwanga Kakule (1 October 2022). "DR Congo. Dancing to the Rumba Rhythm". www.southworld.net. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- "Congolese Rumba | Tom Schnabel's Rhythm Planet". KCRW. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Stone, Ruth M., ed. (2 April 2010). The Garland Handbook of African Music. Thames, Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9781135900014.

- "La Rumba Congolaise". L'Institut français d'Oak Park – French Institute of Oak Park. 28 February 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Daniel, Yvonne L. P. (1989). Ethnography of Rumba: Dance and Social Change in Contemporary Cuba · Volume 1. Berkeley, California, United States: University of California, Berkeley. p. 88.

- Clark, Duncan A.; Lusk, Jon; Ellingham, Mark; Broughton, Simon, eds. (2006). The Rough Guide to World Music: Africa & Middle East. London, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 75. ISBN 9781843535515.

- Malu, Muriel D. M. (2019). Congo Brazzaville (in French). Paris, France: Éditions Karthala. p. 242. ISBN 9782811125943.

- Green, Thomas A.; Svinth, Joseph R. (11 June 2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation [2 Volumes]. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 44. ISBN 9781598842432.

- Ochoa, Todd Ramón (2010). Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba. Oakland, California, United States: University of California. p. 79. ISBN 9780520256835.

- Perkins, William Eric, ed. (1996). Droppin' Science: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hip Hop Culture. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States: Temple University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 9781566393621.

- Lanza, Miguel Á. B. (September 1997). "On Congo Cults of Bantu Origin in Cuba". Sage Journals. Thousand Oaks, California, United States. 45 (179): 141–164. doi:10.1177/039219219704517912. S2CID 143537762.

- Pietrobruno, Sheenagh (29 August 2023). Salsa and Its Transnational Moves. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Lexington Books. p. 35. ISBN 9780739110539.

- The Encyclopedia of Africa v. 1. 2010 p. 407.

- Storm Roberts, John (1999). The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-19-976148-7.

- "Soukous dance king rules Kinshasa (BBC)"

- Anheier, Helmut K.; Isar, Yudhishthir R., eds. (21 January 2010). Cultures and Globalization: Cultural Expression, Creativity and Innovation. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. p. 119. ISBN 9780857026576.

- Knights, Vanessa (29 April 2016). Music, National Identity and the Politics of Location: Between the Global and the Local. Thames, Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. p. 45. ISBN 9781317091608.

- Roberts, Afro-Cuban Comes Home (1986).

- "Wendo Kolosoyi". Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- Gary Stewart, Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos, Verso Books, 2003, p.17-21

- Antoine Manda Tchebwa, Terre de la chanson. La musique zaïroise hier et aujourd'hui, De Boeck – Duculot, 1996

- "An Introduction to Franco Luambo Makiadi". kenyapage.net. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- Roberts, John Storm. Afro-Cuban Comes Home: The Birth and Growth of Congo Music. Original Music cassette tape (1986)

- "La Rumba Congolaise". L'Institut français d'Oak Park – French Institute of Oak Park. 28 February 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Network, World Music. "Tabu Ley Rochereau Receives Award". World Music Network. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Ray, Rita. "What made Papa Wemba so influential?". Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- Trillo, Richard (2016). The Rough Guide to Kenya. London, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 598. ISBN 9781848369733.

- "congolese rumba". Cavacha Express! Classic congolese hits. 19 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Stone, Ruth M., ed. (2 April 2010). The Garland Handbook of African Music. Thames, Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9781135900014.

- "Shauri Yako — Orchestra Super Mazembe". Last.fm. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- "congo in kenya". muzikifan.com. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Nyanga, Caroline. "Stars who came for music and found eternal resting place". The Standard. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- Pietromarchi, Virginia. "'The soul of the Congolese': Rumba added to UNESCO heritage list". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- "43 elements inscribed on UNESCO's inscribed on UNESCO's intangible cultural heritage lists". UNESCO. 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021.

- Stone, Ruth. Ed. (1998: 360). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. v. 1 Africa. New York: Garland. ISBN 0824060350

- Stone, Ruth. Ed. (1998: 361). The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. v. 1 Africa.

- After Banning Eyre (2006: 13). "Highlife guitar example" Africa: Your Passport to a New World of Music. Alfred Pub. ISBN 0-7390-2474-4

- Stone, Ruth. Ed. (1998: 365). Excerpt from a Choc Stars seben. Original transcription by Banning Eyre. The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. v. 1 Africa.

- Malandra, Ocean (December 2020). Moon Cartagena & Colombia's Caribbean Coast. New York City, New York State, United States: Avalon Publishing. ISBN 9781640499416.

- Koskoff, Ellen, ed. (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Africa; South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean; The United States and Canada; Europe; Oceania. Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 9780415994033.

- Valdés, Vanessa K., ed. (June 2012). Let Spirit Speak!: Cultural Journeys Through the African Diaspora. Albany, New York City, New York State: State University of New York Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781438442174.

- Hodgkinson, Will (8 July 2010). "How African music made it big in Colombia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Slater, Russ (17 January 2020). "Colombia's African Soul". Long Live Vinyl. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Mwamba, Bibi (7 February 2022). "L'influence de la rumba congolaise sur la scène musicale mondiale". Music in Africa (in French). Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Schwegler, Armin; Kirschen, Bryan; Maglia, Graciela, eds. (19 December 2017). Orality, Identity, and Resistance in Palenque (Colombia): An Interdisciplinary Approach. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 15–104. ISBN 9789027264954.

- "Shakira Brought Afro-Colombian Dance to the Super Bowl". www.okayafrica.com. 2 February 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Lavaine, Bertrand (8 January 2021). "Coupé décalé, tempo sulfureux". RFI Musique (in French). Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Ciyow, Yassin (25 July 2022). ""C'est la musique préférée des Ivoiriens" : à Abidjan, les Congolais entretiennent la flamme de la rumba". Le Monde.fr (in French). Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- Isar, Yudhishthir Raj (31 March 2012), Cultures and Globalization: Cities, Cultural Policy and Governance, London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd, p. 174, ISBN 9781446291726, retrieved 23 August 2023

- Nuttall, Sarah (2006). African and Diaspora Aesthetics. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 84–92. ISBN 978-0-8223-3907-6.

- Conteh-Morgan, John; Olaniyan, Tejumola (October 2004). African Drama and Performance. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-253-21701-1.

- White, Bob W. (27 June 2008). Rumba Rules: The Politics of Dance Music in Mobutu's Zaire. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 48–61. ISBN 978-0-8223-8926-2.

- Légendes urbaines – Dj Arafat, la renaissance [Urban legends – Dj Arafat, the rebirth] (in French), RFI Musique, 20 March 2019, retrieved 23 August 2023

- Fonseca, Anthony J.; Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn (9 September 2021). Listen to Hip Hop!: Exploring a Musical Genre. New York, New York State, United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. pp. 239–245. ISBN 978-1-4408-7488-8.

- Charry, Eric S. (2012). Hip Hop Africa: New African Music in a Globalizing World. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-253-00307-2.

- Sterling, Christopher H. (25 September 2009). Encyclopedia of journalism. 6. Appendices. Thousand Oaks, California, United States: SAGE. p. 1289. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

- Alim, H. Samy; Ibrahim, Awad; Pennycook, Alastair (October 2008). Global Linguistic Flows: Hip Hop Cultures, Youth Identities, and the Politics of Language. Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 141–145. ISBN 978-1-135-59299-8.

- Bennett, Andy; Waksman, Steve (16 December 2014). The SAGE Handbook of Popular Music. Thousand Oaks, California, United States: SAGE. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-4739-1099-7.

- "Bisso Na Bisso – Finest African Hip Hop Music". African Music Safari. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn; Fonseca, Anthony J. (1 December 2018). Hip Hop around the World [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]. Santa Barbara, California, United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-313-35759-6.

- "African Music Spotlight: Bisso Na Bisso Brought African Heritage to French Rap". AfricaOTR. 23 June 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- Paravisini-Gebert, Lisa (5 July 2017). "How French hip hop found its own voice by going back to Africa". Repeating Islands. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- Sar, Yerim (9 May 2018). "Le Congo dans le rap français". www.booska-p.com (in French). Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- Cynthia, N. (22 June 2020). "L'influence de l'Afrique dans le rap français". Youtrace.tv (in French). Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- Kambala, Etienne (11 November 2022). "France : La liste non exhaustive des rappeurs originaires de deux Congo". Eventsrdc.com (in French). Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- Kambala, Etienne (29 September 2022). "Comment le Congo a transformé le rap français ? (EXPLICATIONS)". Eventsrdc.com (in French). Retrieved 24 August 2023.

Bibliography

- Gary Stewart (2000). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-368-9.

- Wheeler, Jesse Samba (March 2005). "Rumba Lingala as Colonial Resistance". Image & Narrative (10).