Francesco Hayez

Francesco Hayez (Italian: [franˈtʃesko ˈaːjets]; 10 February 1791 – 12 February 1882) was an Italian painter. He is considered one of the leading artists of Romanticism in mid-19th-century Milan, and is renowned for his grand historical paintings, political allegories, and portraits.[1]

Francesco Hayez | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait at the age of 88 in 1879 | |

| Born | 10 February 1791 |

| Died | 12 February 1882 (aged 91) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Romanticism |

Biography

Francesco Hayez was from a relatively poor family from Venice. His father, Giovanni, was of French origin while his mother, Chiara Torcella, was from Murano. Francesco was the youngest of five sons. He was brought up by his mother's sister, who had married Giovanni Binasco, a well-off shipowner and art collector. Hayez displayed a predisposition for drawing since childhood. His uncle, having noticed his precocious talent, apprenticed him to an art restorer in Venice. Hayez would later become a pupil of the painter Francesco Maggiotto with whom he continued his studies for three years. He was admitted to the painting course of the New Academy of Fine Arts in Venice in 1806, where he studied under Teodoro Matteini. In 1809 he won a competition from the Academy of Venice for a one-year residency at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome. He remained in Rome until 1814, then moved to Naples where he was commissioned by Joachim Murat to paint a major work depicting Ulysses at the court of Alcinous. In the mid-1830s he attended the Maffei Salon in Milan, hosted by Clara Maffei. Maffei's husband would later commission Hayez a portrait of his wife. In 1850 Hayez was appointed director of the Brera Academy.

Over the course of a long career, Hayez proved to be particularly prolific. His output included historic paintings designed to appeal to the patriotic sensibility of his patrons as well as works reflecting the desire to accompany a Neoclassic style to grand themes, either from biblical or classical literature. He also painted scenes from theatrical presentations. Conspicuously absent from his oeuvre, however, are altarpieces - possibly due to the Napoleonic invasions that deconsecrated many churches and convents in Northern Italy. Art historian Corrado Ricci described Hayez as a classicist who then evolved into a style of emotional tumult.[2]

.jpg.webp)

His portraits have the intensity of Ingres and the Nazarene movement. Often sitting, Hayez's subjects are often dressed in austere, black and white clothing, with little to no accoutrements. While Hayez made portraits for the nobility, he also explored other subjects like fellow artists and musicians. Late in his career, he is known to have worked using photographs.

One of Hayez's favorite themes was semi-clothed Odalisque evocative of oriental themes – a favorite topic of Romantic painters.[3] The depictions of harems and their women allowed artists the ability to paint scenes otherwise not acceptable within society. Even Hayez's Mary Magdalene has more sensuality than religious fervor.

Hayez's painting The Kiss was considered among his best work by his contemporaries, and is possibly his most well-known effort. The anonymous, unaffected gesture of the couple does not require knowledge of myth or literature to interpret, and appeals to a modern gaze.[4]

A scientific assessment of Hayez's career has been made complicated by his proclivity for not signing or dating his works. Often dates in his paintings indicate when the work was acquired or sold, not the time of its creation. Moreover, he often painted the same compositions several times with minimal variations if any at all.

Among his pupils from the Brera Academy were Carlo Belgioioso, Amanzio Cattaneo, Alessandro Focosi, Giovanni Battista Lamperti, Livo Pecora, Angelo Pietrasanta, Antonio Silo, Ismaele Teglio Milla and Francesco Valaperta.[5][6]

Hayez died in Milan, age 91. His studio at the Brera Academy is marked with a plate.

Gallery

- See also Category:Paintings by Francesco Hayez.

Reclining Odalisque (1839)

Reclining Odalisque (1839) Portrait of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli

Portrait of Gian Giacomo Poldi Pezzoli_La_distruzione_del_tempio_di_Gerusalemme_-Francesco_Hayez_-_gallerie_Accademia_Venice.jpg.webp) Destruction of Temple of Jerusalem (1867)

Destruction of Temple of Jerusalem (1867) Crusaders Thirsting near Jerusalem (1836–1850)

Crusaders Thirsting near Jerusalem (1836–1850) Refugees of Parga (1831)

Refugees of Parga (1831) Scene from Byron's drama The Two Foscari (Antonio Bernocchi family collection, today in the Museum of Fondazione Cariplo)

Scene from Byron's drama The Two Foscari (Antonio Bernocchi family collection, today in the Museum of Fondazione Cariplo) Sicilian Vespers scene 1 (1821–22)

Sicilian Vespers scene 1 (1821–22) Sicilian Vespers scene 3 (1821–22)

Sicilian Vespers scene 3 (1821–22) Meeting of Esau and Jacob

Meeting of Esau and Jacob New Favorite in Harem

New Favorite in Harem Portrait, Ballerina Carlotta Chabert as Venus (1830)

Portrait, Ballerina Carlotta Chabert as Venus (1830) Ruth (1835)

Ruth (1835) Odalisque (1867)

Odalisque (1867) Susanna at her Bath (1859)

Susanna at her Bath (1859) Nude Bather

Nude Bather Odalisque with Book (1866)

Odalisque with Book (1866) The Meditation (1851)

The Meditation (1851) Ciociara[7]

Ciociara[7] Samson and the Lion (1842)

Samson and the Lion (1842) Portrait, Matilde Juva-Branca (1851)

Portrait, Matilde Juva-Branca (1851) Portrait, Princess di Sant' Antimo (1840–1844)

Portrait, Princess di Sant' Antimo (1840–1844) Portrait, Antonietta Tarsis Basilico (1851)

Portrait, Antonietta Tarsis Basilico (1851) Portrait, Felicina Caglio Perego di Cremnago (1842)

Portrait, Felicina Caglio Perego di Cremnago (1842) Portrait, Antonietta Vitali Sola (1823)

Portrait, Antonietta Vitali Sola (1823) Portrait, Antonio Rosmini (1835)

Portrait, Antonio Rosmini (1835) Portrait, Camillo Benso, Conte of Cavour (1864)

Portrait, Camillo Benso, Conte of Cavour (1864) Portrait, Massimo d'Azeglio (1860)

Portrait, Massimo d'Azeglio (1860) Portrait, Alessandro Manzoni (1841)

Portrait, Alessandro Manzoni (1841) Portrait, Conte Ninni (1823)

Portrait, Conte Ninni (1823) Levite Ephraim (1842–1844)

Levite Ephraim (1842–1844) The Victorious Athlete (1813)

The Victorious Athlete (1813) Vengeance is Sworn (1851)

Vengeance is Sworn (1851) Secret Accusation (1847–1848)

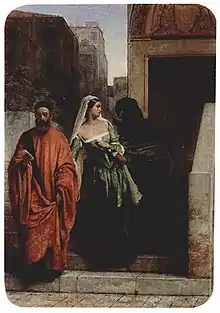

Secret Accusation (1847–1848) Revenge of a Rival (The Venetian Woman) (1853)

Revenge of a Rival (The Venetian Woman) (1853)

References

- "PITTORI e SCULTORI ITALIANI" (in Italian).

- Corrado Ricci (1911) Art in Northern Italy. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 95.

- See Ingres' Grande Odalisque

- Alfredo Melani (1905). "Tranquillo Cremona - Painter", Studio International, Vol. 33, pp. 43-45.

- Delle arti del designo e degli artisti nelle provincie di Lombardia dal 1777-1862 by Antonio Caini (1862). Presso Luigi di Giacomo Pirola, Milan. Page 61.

- Angelo Pietrasanta: un protagonista della pittura lombarda, by Laura Putti, Sergio Rebora, editor Silvana, 2009.

- A derogatory term used in Rome in the nineteenth century to ridicule the poor shepherds of the mountain regions; the term was then used by the painters of the time for their portraits.