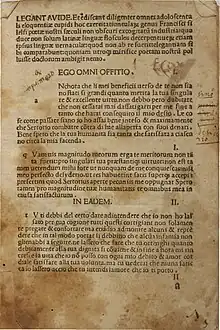

Francesco Filelfo

Francesco Filelfo (Latin: Franciscus Philelphus; 25 July 1398 – 31 July 1481) was an Italian Renaissance humanist and author of the philosophic dialogue On Exile.

Biography

Filelfo was born at Tolentino, in the March of Ancona. He is believed to be a third cousin of Leonardo da Vinci. At the time of his birth, Petrarch and the students of Florence had already begun to exalt the recovery of classic texts and culture. They had created an eager appetite for the antique, had rediscovered many important Roman authors, and had freed Latin scholarship to some extent from the restrictions of earlier periods. Filelfo was destined to carry on their work in the field of Latin literature and as an agent in the still unaccomplished recovery of Greek culture.[1]

In Venice

His earliest studies in grammar, rhetoric and the Latin language were conducted at Padua under the Humanist educator Gasparino Barzizza.[2] During these studies, Filelfo acquired so great a reputation for learning that in 1417, when he was eighteen,[3] he was invited to teach eloquence and moral philosophy at Venice. According to the custom of that age in Italy, it became his duty to explain the language, and to illustrate the beauties of the principal Latin authors, with Cicero and Virgil considered the chief masters of moral science and of elegant diction.[1]

He was admitted to the society of the first scholars and the most eminent nobles. In 1419 he received an appointment from the state, which enabled him to reside as notary and chancellor to the Baile of the Venetians in Constantinople. This appointment was an honour for Filelfo as a man of trust and general ability, and gave him the opportunity of acquiring the most coveted of all possessions at that moment — a scholar's knowledge of the Greek language. Immediately after his arrival in Constantinople at the end of 1420, Filelfo placed himself under the tuition of John Chrysoloras, whose name was already well known in Italy as that of his uncle Manuel Chrysoloras, the first Greek to profess the literature of his ancestors in Florence.[1]

He assumed his charge of chancellor for the bailo Benedetto Emo (summer 1421 to summer 1423), with diplomatic missions. In late 1421, he accompanied Emo during an embassy to the Ottoman Sultan Murad II, who was the candidate supported by Venice for the succession of the late Sultan Mehmed I. In contrast, the Byzantines supported the candidacy of the pretender Mustafa. This would have been difficult for the pupil of John Chrysoloras. The final victory of Murad II resulted in the siege of Constantinople in spring 1422. It was during the great assault of 22 August 1422 that his professor, mortally ill, dictated to him his will. Nominated executor of this will with the widow of the dead, Manfredina Doria, he was also designated tutor of Chrysoloras' girls. After the completion of his term as chancellor in July 1423, he entered the service of the emperor John VIII Palaeologus who sent him immediately to Sigismond, King of Hungary. Before his departure, his marriage with Theodora, the daughter of John Chrysoloras, was decided, and was concluded when he returned from Hungary after sixteenth months of absence (end October 1424). With a new teacher, Chrysococes, he acquired a thorough knowledge of Greek and formed a large collection of Greek manuscripts. In 1427, he accepted an invitation from the Venetian Republic, and set sail for Italy, intending to resume his professorial career. From this time forward until the date of his death, Filelfo's biography consists of a record of the various towns in which he lectured, the masters whom he served, the books he wrote, the authors he illustrated, the friendships he contracted, and the wars he waged with rival scholars. He was a man of vast physical energy, of inexhaustible mental activity, of quick passions and violent appetites; vain, restless, greedy of gold and pleasure and fame; unable to stay quiet in one place, and perpetually engaged in quarrels with his peers.[1]

In Tuscany

When Filelfo arrived at Venice with his family in 1427, he found the city had almost been emptied by the plague. He therefore moved to Bologna; but the city was too much disturbed with political dissensions to attend to him; so Filelfo crossed the Apennines and settled in Florence. During the week he lectured to large audiences of young and old on the principal Greek and Latin authors, and on Sundays he explained Dante to the people in the Duomo.[1]

In addition to these labours of the chair, he found time to translate portions of Aristotle, Plutarch, Xenophon and Lysias from the Greek. Nor was he dead to the claims of society. At first, he seems to have lived with the Florentine scholars on tolerably good terms; but he was so arrogant that Cosimo de' Medici's friends were not long able to put up with him. Filelfo hereupon broke out into open and violent animosity; and when Cosimo was exiled by the Albizzi party in 1433, he urged the signoria of Florence to pronounce upon him the sentence of death. On the return of Cosimo to Florence, Filelfo's position in that city was no longer tenable. His life, he asserted, had been already once attempted by a cut-throat in the pay of the Medici; and now he readily accepted an invitation from the state of Siena. In Siena, however, he was not destined to remain more than four years. His fame as a professor had grown great in Italy, and he daily received tempting offers from princes and republics. The most alluring of these, made him by the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, he decided to accept; and in 1440 he was received with honour by his new master in the capital of Lombardy.[1]

In Lombardy

Filelfo's life at Milan curiously illustrates the multifarious importance of the scholars of that age in Italy. It was his duty to celebrate his princely patrons in panegyrics and epics, to abuse their enemies in libels and invectives, to salute them with encomiastic odes on their birthdays, and to compose poems on their favorite themes. For their courtiers he wrote epithalamial and funeral orations; ambassadors and visitors from foreign states he greeted with the rhetorical lucubrations then so much in vogue. The students of the university he taught in daily lectures, passing in review the weightiest and lightest authors of antiquity, and pouring forth a flood of miscellaneous erudition.[1]

Not satisfied with these outlets for his mental energy, Filelfo went on translating from the Greek, and prosecuted a paper warfare with his enemies in Florence. He wrote, moreover, political pamphlets on the great events of Italian history; and when Constantinople was taken by the Turks, he procured the liberation of his wife's mother, Manfredina Doria, by a message addressed in his own name to the sultan. In addition to a fixed stipend of some 700 golden florins yearly, he was continually in receipt of special payments for the orations and poems he produced; so that, had he been a man of frugal habits or of moderate economy, he might have amassed a considerable fortune. As it was, he spent his money as fast as he received it, living in a style of splendour and self-indulgence. In consequence of this prodigality, he was always poor. His letters and his poems abound in demands for money from patrons, some of them couched in language of the lowest adulation, and others savouring of literary brigandage.[1]

During the second year of his Milanese residence Filelfo lost his first wife, the Greek Theodora. He soon married again; and this time he chose for his bride a young lady of good Lombard family, called Orsina Osnaga. When she died he took in wedlock for the third time a woman of Lombard birth, Laura Magiolini.[4]

On the death of Visconti in 1447, Filelfo, after a short hesitation, transferred his allegiance to Francesco Sforza, husband of Bianca, Visconti's only child, who would become Duke of Milan in 1450. In order to curry favor with this parvenu, he began his ponderous epic, the Sforziad, of which 12,800 lines were written, but which was never published. Some years after the deaths of Francesco and Bianca (1466 and 1468, respectively), Filelfo turned his thoughts towards Rome. He was now an old man of seventy-seven years, honored with the friendship of princes, recognised as the most distinguished of Italian humanists, courted by pontiffs, and decorated with the laurel wreath and the order of knighthood by kings.[5]

Crossing the Apennines and passing through Florence, he reached Rome in the second week of 1475. Pope Sixtus IV now ruled in the Vatican, and Filelfo had received an invitation to occupy the chair of rhetoric with good emoluments. At first he was pleased with the city and court of Rome; but his satisfaction turned to discontent, and he gave vent to his ill-humour in a venomous satire on the pope's treasurer, Milliardo Cicala. Sixtus himself soon fell under the ban of his displeasure; and when a year had passed he left Rome never to return. Filelfo reached Milan to find that his wife had died of the plague in his absence, and was already buried.[5]

Return to Tuscany

For some time past he had been desirous of displaying his abilities and adding to his fame in Florence. Years had healed the breach between him and the Medici family; and on the occasion of the Pazzi conspiracy against the life of Lorenzo de' Medici, he had sent violent letters of abuse to his papal patron Sixtus, denouncing his participation in a plot so dangerous to the security of Italy. Lorenzo now invited him to profess Greek at Florence, and so Filelfo went there in 1481. Two weeks after his arrival he succumbed to dysentery, and was buried at the age of eighty-three in the Church of the Annunziata.[5]

A complete edition of Filelfo's Greek letters (based on the Codex Trevulzianus) was published for the first time, with French translation, notes and commentaries, by Emile Legrand in 1892 at Paris (C. xii. of Publications de l'école des lang. orient.).[5]

Notes

- Symonds 1911, p. 341.

- Swisher, Samuel (1991). Humanism and the Council of Florence, 1438-1439 (PDF). Denton, TX. pp. 3–4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Symonds 1911, pp. 341–342.

- Symonds 1911, p. 342.

References

- Rosmini, C. (1808). Vita di Francesco Filelfo da Tolentino. Milan.

- Robin, M. (1991). Filelfo in Milan. Writings 1451-1477. Princeton.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Viti, P. (1997). "Filelfo, Francesco". Dizionario biografico degli Italiani. Rome. p. 624.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ganchou, Th. (2005). "Les ultimae voluntates de Manuel et Iôannès Chrysolôras et le séjour de Francesco Filelfo à Constantinople". Bizantinistica. VII: 195–285.

- Meserve, Margaret (2010). "Nestor Denied: Francesco Filelfo's Advice to Princes on the Crusade against the Turks". Osiris. 25 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1086/657262. S2CID 154515098.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Symonds, John Addington (1911). "Filelfo, Francesco". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 341–342. Symonds appended his own assessment of Filelfo's work.