Frank Howard (baseball)

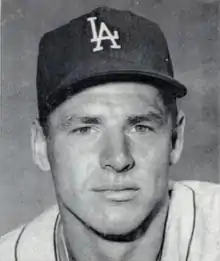

Frank Oliver Howard (born August 8, 1936), nicknamed "Hondo", "the Washington Monument" and "the Capitol Punisher", is an American former player, coach and manager in Major League Baseball who played most of his career for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Washington Senators/Texas Rangers franchises. One of the most physically intimidating players in the sport, Howard was 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m) tall and weighed between 275 to 290 pounds (125 to 132 kg), according to former Senators/Rangers trainer Bill Zeigler.

| Frank Howard | |

|---|---|

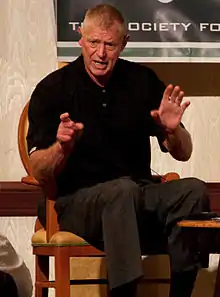

Howard in 2009 | |

| Outfielder / First baseman | |

| Born: August 8, 1936 Columbus, Ohio, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 10, 1958, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 30, 1973, for the Detroit Tigers | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .273 |

| Home runs | 382 |

| Runs batted in | 1,119 |

| Teams | |

As player

As manager As coach | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Howard was named the National League's Rookie of the Year in 1960 for the Dodgers. He twice led the American League in home runs and total bases and once each in slugging percentage, runs batted in and walks. His 382 career home runs were the eighth most by a right-handed hitter when he retired; his 237 home runs and 1969 totals of 48 home runs and 340 total bases in a Washington uniform are a record for any of that city's several franchises. Howard's Washington/Texas franchise records of 1,172 games, 4,120 at bats, 246 home runs, 1,141 hits, 701 RBI, 544 runs, 155 doubles, 2,074 total bases and a .503 slugging percentage have since been broken.

Early life

Howard was born in Columbus, Ohio, to John and Erma Howard, the third of six children. His father was a machinist for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway and had played semi-professional baseball, later on encouraging his son's interest in the game.[1]

Howard attended South High School in Columbus, Ohio, and Ohio State University, where he played college baseball and college basketball for the Ohio State Buckeyes. He was an All-American in both basketball and baseball.[2] He averaged 20.1 points and 15.3 rebounds in 1957, and was drafted the following year by the Philadelphia Warriors of the National Basketball Association.[1]

Professional career

Los Angeles

Howard instead signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers organization, and won The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year Award in 1959 after hitting 43 homers in the Pacific Coast League. After a handful of appearances in 1958 and 1959 he succeeded former Brooklyn Dodger All-Star Carl Furillo as Los Angeles' right fielder in 1960. He was named the NL's Rookie of the Year after batting .268 with 23 home runs and 77 runs batted in (RBIs). His teammates gave him the nickname "Hondo" after the character in a John Wayne film.[3]

Howard hit 98 home runs in the following four seasons, most prominently in a 1962 campaign in which he batted .296 with 31 home runs and finished among the NL's top five players in RBIs (119) and slugging (.560). He won the NL Player of the Month award in July with a .381 average, 12 home runs, and an incredible 41 RBIs. As an outfielder starting 127 games (completing just 91), Howard was credited with 19 outfield assists (the league leader, Johnny Callison, starting 147 games had just five more). The season ended with the Dodgers and San Francisco Giants tied for first place. In the three-game pennant playoff that followed Howard had only a single in 11 at-bats and struck out three times against Billy Pierce in the first game, including the final out; but he had a run and an RBI in the second contest, an 8–7 win. The Giants took the pennant in three games, but Howard ended up ninth in the MLB Most Valuable Player award voting.

In 1963 his production dropped off to a .273 average, 28 homers and 64 RBIs; but the Dodgers won the pennant, and his upper-deck solo home run off Whitey Ford broke a scoreless tie in the fifth inning of Game 4 of the World Series, helping Los Angeles to a 2–1 win and a sweep of the New York Yankees. He again hit over 20 home runs in 1964, and on June 4 his three-run home run in the seventh inning provided all the scoring in Sandy Koufax's third no-hitter, a 3–0 defeat of the Philadelphia Phillies; Howard had also homered for the final run in Koufax's first no-hitter on June 30 two years earlier, a 5–0 win over the New York Mets. But the team's 1962 move into pitcher-friendly Dodger Stadium hurt power hitters, and speedier outfielders like spray-hitting Willie Davis were seen as more in line with the club's future.

Howard's .226 batting average in 1964—combined with regularly high strikeout totals—led to his December trade to the Washington Senators, an expansion franchise that replaced the original Senator team, which had relocated to Minnesota and become the Minnesota Twins. The seven-player deal included future All-Star pitcher Claude Osteen to Los Angeles to further strengthen its already powerful starting rotation. In 2005 Howard recalled welcoming the trade despite going from a pennant contender to a weak expansion team, noting, "I was essentially a fourth outfielder in L.A., hitting 25 home runs a year in the biggest baseball park in America and doing it on 400 at-bats." He added, "What could I do if I get 550 at-bats? I had my best years here."

Washington

Shifted to left field in Washington, Howard was unquestionably the center of the offense, leading the team in homers and RBI in each of his seven seasons there. But under managers Gil Hodges, Jim Lemon, and Ted Williams, the Senators were a woeful bunch, achieving only one winning season in that time. In 1967 he hit 36 homers, third in the AL behind Harmon Killebrew and Carl Yastrzemski, as he entered the peak years of his career. During an amazing one-week stretch in the spring of 1968 (May 12–18), Howard hammered 10 home runs in 20 at bats, with at least one in six consecutive games; his 10 home runs are also the most ever in one week. He would go on to hit 13 homers in 16 games, a mark that still stands, matched only by Albert Belle in 1995. Howard finished the season leading the AL with 44 home runs, a .552 slugging percentage and 330 total bases, and was second to Ken Harrelson with 106 RBI; he made his first of four consecutive All-Star teams that year (notably, at the rather late-maturing age of 31 after winning Rookie-of-the-Year honors with the Dodgers at age 23 eight seasons before) and placed eighth in the MVP balloting, although the Senators finished in tenth (last) place with a 65–96 record. His hitting accomplishments in 1968 were all the more impressive, considering that pitching dominated that year; 1968 has often been referred to as the "Year of the Pitcher".

Howard wore #9 from the time he joined the Senators through 1968. When new owner Bob Short signed retired slugger Williams to manage the club, Howard happily surrendered #9 so the Hall of Famer could wear it once again; Howard donned #33 for the start of the 1969 season. Williams played a major role in teaching him to be more patient at the plate, asking the slugger, "Can you tell me how a guy can hit 44 home runs and only get 48 bases on balls?" He encouraged Howard to lay off the first fastball he saw, and work pitchers deeper into the count, advice which resulted in Howard's walk totals nearly doubling and 45 fewer strikeouts the first year. A year later Howard added 32 more walks to lead the AL with a whopping 132.

Beginning in 1968 Howard appeared semi-regularly at first base in order to limit the wear and tear of playing the outfield daily. In 1969, he hit career highs with 48 homers (one behind Killebrew's league lead), 111 runs (second in the AL to Reggie Jackson), a .296 batting average and a .574 slugging mark. On Howard's broad shoulders, the Senators had their best year ever, 86–76, but still finished far behind the Baltimore Orioles in the Eastern Division. He again led the AL with 340 total bases, the most ever by a Washington player, and added 111 RBI; his fourth-place finish in the MVP vote was the highest of his career. In 1970 he led the AL both in home runs (44) and RBI (126); his 132 walks in that year also topped the league, and remain a franchise record. On September 2, he received three intentional walks from flamethrowing southpaw Sam McDowell—two of them to lead off an inning. He came in fifth in the 1970 MVP race, and received one first-place vote.

Howard hit the last regular-season home run for the Senators in RFK Stadium in his final at bat on September 30, 1971 off Yankees pitcher Mike Kekich. After waving to the cheering fans, Howard tossed his batting helmet into the stands, and after the game said "This is utopia for me."[4]

Later years

The Senators moved to Dallas/Fort Worth in 1972, becoming the Texas Rangers. Howard batted only .244 with 9 home runs in 95 games before his contract was sold to the Detroit Tigers in August; he had just one home run in 33 games for division champion Detroit, and was ignominiously left off its postseason roster. His final big league season was 1973, hitting .256 average and 12 home runs playing DH. Unable to find a job in the majors in 1974, Howard signed to play in Japan's Pacific League for the Taiheiyo Club Lions. In his first at bat there he swung mightily and hurt his back, and never played again.

In 16 Major League seasons Howard batted .273, had a .499 slugging percentage, hit 382 home runs, and drove in 1,119 RBI in 1,895 games played. His lifetime marks included 864 runs, 1,774 hits, 245 doubles, 35 triples, eight stolen bases and a .352 on-base percentage; his 1,460 strikeouts, the product of a long swing, fence-busting power, and an enormous strike zone, were then the fifth highest total in major league history.

As manager and coach

Following his retirement as a player Howard coached for the Milwaukee Brewers from 1977 to 1980 before being named manager of the 1981 San Diego Padres. The team finished in last place in both halves of that strike-marred season, and Howard was let go. Catching on as a coach with the Mets in 1982, he took over as manager for the last 116 games in 1983 after George Bamberger resigned,[5] but again finished in last place.

In all he posted a 93–133 career managerial record. Howard also coached again for the Brewers (1985–86), Mets (1994–96), Seattle Mariners (1987–88), Yankees (1989, 1991–93), and Tampa Bay Devil Rays (1998–99). Since 2000 he has worked for the Yankees as a player development instructor.

Back in 1972 Howard had thought that before much time had passed another President would deliver the opening-day pitch in the capital; he was only off by over three decades. On April 14, 2005, baseball returned to Washington. Reflecting on its '71 departure he remarked, "I thought that within five years it would be back. Well, 34 years later, here we are." During pregame ceremonies before the Washington Nationals–Arizona Diamondbacks game at RFK Stadium which featured players from both former Senators clubs, Howard walked out to left field and was greeted by a raucous ovation. At age 68, he joked, "I know I'm going to left field – if I can make it that far without having a coronary! I used to be able to sprint out there but I don't even know if I'll be able to jog. I told (former Senator Ed) Brinkman, 'For crissakes, call 911 if I have a blowout in left field.'"[6]

Howard now helps raise money for St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Personal life

Howard has married twice. His first marriage was to Carol Johanski, a secretary who worked at the Green Bay Gazette. The couple met and married in 1958 and settled in Green Bay, Wisconsin, going on to raise six children. The marriage ended in divorce and Howard remarried in 1991, to his second wife Donna.[1]

See also

References

- "Frank Howard (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

- "Frank Howard, Class of 2008". Ohio Basketball Hall of Fame.

- Jaffe, Harry (April 4, 2009). "Heavy Hitters". washingtonian.com. Washingtonian Media Inc. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- "The Milwaukee Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- Bamberger quits as Mets manager; Howard names

- Oldenburg, Don (March 22, 2005). "No Place Like Home". The Washington Post.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Frank Howard managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Frank Howard at the SABR Baseball Biography Project