Freddie Brown (cricketer)

Frederick Richard Brown CBE (16 December 1910 – 24 July 1991[1]) was an English amateur cricketer who played Test cricket for England from 1931 to 1953, and first-class cricket for Cambridge University (1930–31), Surrey (1931–48), and Northamptonshire (1949–53). He was a genuine all-rounder, batting right-handed and bowling either right-arm medium pace or leg break and googly.

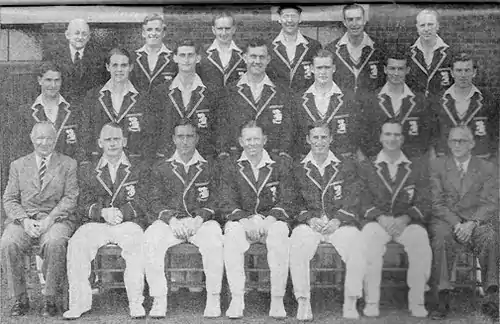

Brown in about 1935 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Frederick Richard Brown | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 16 December 1910 Lima, Peru | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 July 1991 (aged 80) Ramsbury, Wiltshire, England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting | Right-handed | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling | Right-arm medium Right-arm legbreak | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut | 29 July 1931 v New Zealand | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 30 June 1953 v Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: Cricinfo, 23 January 2022 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Brown was named one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1933, but his career declined thereafter until he was made captain of Northamptonshire and England in 1949. Brown was an England selector from 1951 to 1953 and Chairman of Selectors in 1953 when England regained the Ashes. Subsequently, he was involved in cricket administration including tour management. He was elected President of Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) in 1971–72 and Chairman of the Cricket Council in 1977. He was awarded the MBE in 1942 for his gallantry in the evacuation of the British Army from Crete and the CBE in 1980 for services to cricket.

Early life and development as a cricketer

Brown was the son of Roger Grounds Brown, an English businessman in Peru who was a keen cricketer, opening the batting and taking 5/50 for Lima Cricket and Football Club against Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) in 1926–27.[2] Brown's sister Aline was a left-handed batter for the Women's Cricket Association from 1934 to 1948 and, later, his sons Richard Philip and Christopher Frederick played minor cricket.[3][4] Brown was naturally left-handed, but forced to use his "proper" right hand from an early age, fortunately without affecting his cricket.[5]

He was educated at the Saint Peter's School in Chile, where he played little cricket, and from 1921 at St Piran's school in Maidenhead, where he was taught googly bowling by South African all-rounder Aubrey Faulkner.[6] In 1925, Brown moved to The Leys School in Cambridge and topped the school batting and bowling averages.[5] He continued his studies at St John's College, Cambridge and played for Cambridge University Cricket Club, making his debut in 1930.[5]

First-class career

Pre-war years

Brown scored 52 against the 1930 Australians[7] and took 5/9 against the Free Foresters in the following match, bowling leg-spin.[8] His first century was 150 against Surrey at The Oval, sharing a partnership of 257 for the seventh wicket. He scored his second century in his next innings, making 140 against H. D. G. Leveson-Gower's XI at The Saffrons. At the end of the season, he was top of the Cambridge batting averages.[5]

In 1931, Brown continued to play for Cambridge, taking 5/153 against Oxford University when Iftikhar Ali Khan Pataudi made 238 not out.[5] Brown joined Surrey and ended the season with 107 wickets at an average of 22.65 runs per wicket. He was called up to play against New Zealand in two Test matches; he did not bat in the rain-affected series but took three wickets and held one catch. In 1932, Brown took 120 wickets at 20.46 and made 1,135 runs at 32.42.[9][10] He made his highest first-class score of 212 against Middlesex at The Oval, Wisden Cricketers' Almanack commenting on "a glorious display of fearless hitting" with two sixes out of the ground, another five into the stands and fifteen fours.[5] Brown played against India at Lord's, taking three wickets and scoring 1 and 29. He was subsequently selected for the 1932–33 MCC tour of Australia under his Surrey captain Douglas Jardine. He played in none of the controversial "Bodyline" Tests against Australia, playing only in state matches.[11][12] He played in the two Tests in New Zealand, scoring 74 in 83 minutes in the first Test at Lancaster Park, but was dropped from the England team for its 1933 matches.

Brown was chosen as one of the 1933 Wisden Cricketers of the Year for his "double" of 100 wickets and 1,000 runs in 1932.[5] He played less cricket after 1933 but was recalled for the second Test against New Zealand in 1937 when he hit 57 with a six and 8 fours and took 3/81 and 1/14. He was dropped again and it was thought that his Test career was over. His career-best bowling was 8/34, achieved against Somerset just two weeks before the Second World War began.[13]

Brown took a commission in the Royal Army Service Corps. He helped evacuate the British Army from Crete in 1941 for which he was awarded the MBE in the 1942 New Year Honours List. He played cricket with Lindsay Hassett in Cairo, but was captured with Bill Bowes at Tobruk in 1942 and spent the rest of the war in prisoner-of-war camps in Italy and Germany,[1] where they organised games of cricket, baseball and rugby. He lost over 60lbs (30 kilos) before being liberated by the Americans in 1945.[14]

Career revival

Brown became a medium-paced seamer after the war and organised cricket while working as a welfare officer in a Doncaster colliery. When the coal mines were nationalised Brown lost his job and became the captain and assistant-secretary of Northamptonshire County Cricket Club (Northants) in 1949.[15] This revitalised his career as he scored 1,077 runs at 24.47 and took 111 wickets at 27.00 in 1949, Northants improving from seventeenth and last place in the 1948 County Championship to sixth in 1949.[16] As a result, Brown was asked to captain England in the last two Tests against New Zealand, taking two wickets and four catches in a 0–0 series draw. In 1950, he scored 1,108 runs at 38.20 and took 77 wickets at 28.38.[9][10]

When George Mann and Norman Yardley turned down the captaincy of the 1950–51 tour of Australia, Brown came into consideration and was made captain of the Gentleman against Players at Lord's. He came in at 194/6 and scored 122 out of 131 runs inside two hours, including a six into the Lord's Pavilion. He followed up with three quick wickets and was offered the tour captaincy the same afternoon.[17] Brown had only a modest Test career up to that point, having made only 233 runs at 23.30 and taken 14 wickets at 40.79,[18][19] but this was still a time when the England captain had to be an amateur even if he was a "passenger" in terms of ability. Brown was made captain for the last Test against the West Indies with England already 2–1 down in the series; they lost the final Test by an innings, which did not bode well for the team in Australia.

Australia and New Zealand 1950–51

The 1950–51 England team under Brown's captaincy was regarded as one of the weakest sent to Australia and John Kay commented that without the key players Alec Bedser and Len Hutton, England's standard would have been little better than that of a club team.[20] England lost the Test series 4–1, their only victory being a consolation win in the final Test. Despite his team's poor performance, the forty-year-old Brown enjoyed personal success and won considerable popularity among Australian supporters with his determination to fight on regardless of the odds. Unexpectedly, he scored 210 runs at 26.25 and took 18 wickets at 21.61 in the series, coming third in the England batting averages after Hutton and Reg Simpson and third in the bowling averages after Bedser and Trevor Bailey.[21]

Despite his determination, Brown was an unsuccessful captain and his greatest mistake was to move Hutton down the batting order from one to six in a bid to strengthen the lower order: the result was that Hutton ran out of partners three times in the first two Tests.[11] Kay summarised the tour as "one long succession of inglorious displays that had riled the critics without exception".[22] The team's poor fielding came in for especial criticism and earned them the nickname of Brown's Cows.[23] However, Bill O'Reilly wrote that Brown did a magnificent job as both player and captain through his unselfish devotion to the job, earning the admiration of the Australian supporters.[24]

The first Test at Woolloongabba was decided by a torrential rainstorm which flooded the ground after Australia had scored 228 and turned the wicket into a "sticky dog". Brown had bowled well, taking 2/63 in support of Bedser and Bailey. In the changed conditions, Brown gambled on a declaration at 68/7 so that the Australians would have to bat on the wet pitch before it dried out. Predictably, Australia's batting collapsed and their captain Lindsay Hassett declared at 32/7 to make England bat again. Brown missed an opportunity to save time when he misunderstood how long it took to roll the pitch, given that the ground still used a horse-drawn heavy roller. Next morning, England were all out for 122 and lost by 70 runs.[25][26]

In the second Test at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, Australia were dismissed for 194 and England were reduced to 54/5 before Brown came in to top-score with 62 in England's 197. He won the crowd over with this innings, especially when he hit Ian Johnson straight down the ground for six and through the covers for four. He bowled well and took 4/26 as Australia were out for 181, but England could only score 150 as the hosts won by 28 runs to take a 2–0 lead in the series.[27] In the third Test, Brown made his highest Test score of 79 with another defiant innings after England had been reduced to 137/4. Injuries to Bailey and Doug Wright seriously depleted England's bowling and Brown had to bowl 44 overs to support Bedser and debutant John Warr. He took a commendable 4/153 as Australia totalled 426 before bowling England out again to win the match by an innings and secure the series victory.[28]

The remainder of the series was an anti-climax and Australia won the fourth Test by 274 runs before England restored some pride with a consolation win in the final Test. During the fourth Test, Brown was hospitalised after a motor accident and was unfit to continue playing. He relinquished the captaincy to vice-captain Denis Compton who became the first professional England captain since Jack Hobbs in 1926,[29] Brown was fit to play in the final Test at Melbourne and achieved his best Test bowling figures of 5/49, including a spell of 3/0. England won by 8 wickets, the first Test Australia had lost since 1938.[30][31]

Brown scored 62 against New Zealand in the drawn first Test at Christchurch.[32] He scored 47 and 10 not out in the low-scoring second Test at Basin Reserve, which England won by 6 wickets to give them a 1–0 series win.[33]

Later years

Brown was retained as England captain against South Africa on his return and was made a Test selector.[34] South Africa won the first Test and England the second by 10 wickets. Brown scored 42 out of 211 in the low-scoring third Test, which England won by 9 wickets and took 3/107 in the drawn fourth Test. England sealed a 3–1 series victory with a four-wicket win in the fifth Test, Brown scoring 40.[35] He made 940 runs at 33.57 in 1951 and took 66 wickets at 23.37.[9][10] In 1952, he came close to making a double with 1,073 runs at 28.23 and 95 wickets at 24.77.[9][10] Now 41 years old, Brown retired from the England captaincy and was succeeded by the professional Len Hutton.[5]

In his final first-class season, 1953, Brown scored 849 runs (24.97) and took 87 wickets (20.74).[9][10] He was appointed chairman of the selection committee and recalled himself for the second Test against Australia at the age of 42, agreeing to play just one Test on the request of Len Hutton.[36] Ray Lindwall recalled that most of the England players remembered Brown as captain and called him Skipper out of habit, even the new captain Hutton.[37] Brown scored 22 runs off 14 balls in the first innings and Lindwall says he "pitched and turned his leg-breaks on a good length equally well from either end" to take 4/82.[38] When Hutton damaged a finger trying to take a catch, Brown took over in the field.[39] The match ended in a draw and was his last Test and Brown effectively retired from cricket at the end of the 1953 season, though he made occasional reappearances until 1961.[9][10] He worked as an administrator, tour manager and radio commentator for Test Match Special on BBC Radio and wrote his autobiography Cricket Musketeer in 1954.

Brown managed two England tours: South Africa in 1956–67, in which the Test series was drawn 2–2; and Australia and New Zealand in 1958–59, in which England lost the Ashes to Australia 4–0. In Australia, Brown wanted to make an official complaint about the bowling action of Ian Meckiff, which was widely considered illegal, but team captain Peter May insisted on a diplomatic approach. This failed when the Australian chairman of selectors, Sir Donald Bradman retorted that England must put its own house in order, referring to the dubious actions of Tony Lock and Peter Loader.

Brown was the manager of the Rest of the World cricket team in England in 1970 after the scheduled South African tour was cancelled for political reasons.[40] He was President of MCC in 1971–72.[1] He later served the National Cricket Association and the English Schools Cricket Association. In 1977, Brown was Chairman of the Cricket Council, in which capacity he removed Tony Greig from the England captaincy in the World Series Cricket crisis.[41] He was awarded the CBE for services to cricket in the 1980 Queen's Birthday Honours List.[42]

Style and technique

Brown was a leg-spinner in his youth, but turned to medium paced bowling after the war.[5] He was able to turn or cut the ball with his large hands and was a wicket taker rather than a container of batsmen, but sometimes lost his line and length.[5] As a pace bowler he was more accurate, was able to tie down even the best batsmen and proved adept at breaking solid partnerships.[5] In particular he was able to dismiss the stonewalling Australian captain Lindsay Hassett. He still used his leg-spin when required by conditions or the frailties of the batsmen, sometimes mixing them up in the same over. His bucket hands made him a good catcher and he once caught and bowled Keith Miller in both innings of a Test, so the Australian all-rounder nicknamed him 'C and B'. As a batsman he stuck to the simple expedient of blocking the good balls and thumping the bad ones. With his height, weight and strength he could strike the ball as hard as anyone and once hit a six into the Lord's Pavilion. His first-class centuries were noted for their plentiful boundaries and this was another reason why his was popular with the crowds.[5]

Like many amateur captains, Brown was happy to take advice from his senior professionals and O'Reilly says he "conferred with Len Hutton before he made a bowling change...there was little room for doubt...that Brown had tremendous respect for Hutton's advice on the cricket field".[43] He was also one of the selectors who took the radical step of making Hutton England captain, the first professional to be appointed to the position since 1877. Brown's combative captaincy is best remembered for leading poor teams regardless of the odds, Northants in 1949–53 and England in 1950–51, where he laid the foundations for future success.[5] Allen Synge wrote that Brown as captain in the field took "impressive charge" and it was noticeable that players obeyed his commanding gestures "at the double".[44]

On the 1950–51 tour, Brown allowed the team to socialize more than previous captains had done and saw no reason why he should insist that amateur undergraduates should mix awkwardly with working class professionals, or that veterans should accompany their younger teammates.[45] This led to the usual stories of dissension in the ranks when a team performs badly and Brown hotly denied this.

Personality

There are widely contrasting views about Brown's personality. He was well-liked in Australia when he captained England there in 1950–51 as recorded by O'Reilly (see above). According to Kay, Brown had a hearty appetite for food and drink and was combative and forceful by nature, which endeared him to the Australian public.[46] Jack Fingleton commented: "With his sun-hat on, a 'kerchief tied round his neck, and ambling jovially in the field, Freddie Brown lacked only a wisp of straw in his mouth to make him look like the original Farmer Brown".[6] On the other hand, professional players viewed Brown's silk neckerchief with contempt as it "enhanced the impression of a bumptious windbag".[47] Brown was considered "a bully who preyed on weakness or quirk of character".[47]

When the eighteen-year-old Brian Close was out to a poor stroke on his Ashes debut in 1950–51, Brown was extremely unsympathetic to Close who became distressed by his experiences on the tour.[47] John Kay wrote Brown gave the youngsters Berry and Close "every encouragement and seldom complained at their repeated failures" and "the Yorkshire all-rounder was not as co-operative as he might as been".[46]

Brown caused problems for Fred Trueman when he managed the English cricket team in Australia in 1958–59. Trueman and others believed that people like Brown and his colleague Gubby Allen "epitomised the pompous nature of English cricket in the days of amateurs and professionals, gentlemen and players".[48] It was not just professionals as Brown quarreled with the amateur Trevor Bailey, which led to long-standing mutual antipathy.[49] In Trueman's autobiography, he refers to Brown as "a snob, bad-mannered, ignorant and a bigot".[50] Trueman made a formal complaint about Brown to the team captain, Peter May.[51] Although May was another public school-educated amateur, he supported Trueman and told Brown to "act in a manner befitting someone with managerial responsibility".[51] Tom Graveney commented on the lack of team spirit on the tour, saying that "Freddie Brown, in particular, did a very bad job" and was rude to several team members.[52] Graveney called Brown "a very stuck-up individual – at least when he was sober".[52] Kay said Brown had a tendency to be bombastic in speech and could be forthright and ruthless, sometimes being churlish and rude to sensation-seeking reporters, but was always ready to talk amicably to genuine cricket journalists.[53]

References

- Bateman, pp. 34–35.

- "Lima v MCC". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Lima v MCC". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Lima v MCC". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Wisden obituary". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. 1992. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Fingleton, p.124.

- "Cambridge University v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Cambridge University v Free Foresters". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Batting by season". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Bowling by season". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Kay, p. 29.

- Fingleton, p. 27.

- "Surrey v Somerset, 1939". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Fingleton, pp. 27–30.

- Fingleton, pp.30–31.

- Barclay's World of Cricket, pp.438–441.

- Fingleton, p.71.

- "First-class batting in each season by Freddie Brown". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "First-class bowling in each season by Freddie Brown". CricketArchive. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Kay, p. 220.

- Wisden 1952, pp. 795–96.

- Kay, p. 128.

- Fingleton, pp.61–66.

- O'Reilly, p. 153.

- Fingleton, pp.75–85.

- O'Reilly, pp.35–41.

- Fingleton, pp. 100–117.

- Fingleton, pp. 141–146.

- O'Reilly, p. 185.

- Fingleton, pp. 208–211

- O'Reilly, pp. 150–151.

- "New Zealand v England, First Test". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "New Zealand v England, Second Test". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Wisden 1952, p. 1002.

- "South Africans in England, 1951", Wisden 1952, pp. 209–57.

- Synge, p. 114.

- Lindwall, p. 114.

- Lindwall, p.60.

- Synge, p. 117.

- Swanton, p. 144.

- Synge, p. 165.

- "Freddie Brown". CricketArchive. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- O'Reilly, p. 25.

- Synge, p. 116.

- Fingleton, pp.58–60.

- Kay, p.33.

- Waters, p. 148.

- Waters,148–149.

- Miller, p.80.

- Trueman, p. 219.

- Waters, p. 149.

- Waters, p. 150.

- Kay, pp.30–32.

Bibliography

- E. W. Swanton, ed. (1986). Barclays World of Cricket, 3rd edition. Willow Books.

- Bateman, Colin (1993). If The Cap Fits. Tony Williams Publications. ISBN 1-869833-21-X.

- Freddie Brown, Cricket Musketeer, Nicholas Kaye, 1954

- J.H. Fingleton, Brown and Company, The Tour in Australia, Collins, 1951

- Tom Graveney and Norman Miller, The Ten Greatest Test Teams Sidgewick and Jackson, 1988

- John Kay, Ashes to Hassett, A review of the M.C.C. tour of Australia, 1950–51, John Sherratt & Son, 1951

- Ray Lindwall, Flying Stumps, Marlin Books (1977)

- W.J. O'Reilly, Cricket Task-Force, The Story of the 1950–51 Australian Tour, Werner Laurie, 1951

- Rothmans Book of Test Matches, England v Australia 1946–63, Arthur Barker Ltd (1964)

- Allen Synge, Sins of Omission, The Story of Test Selectors, Pelham Books (1990)

- E.W. Swanton, Swanton in Australia with MCC 1946–1975, Fontana/Collins, 1975

- Trueman, Fred (2004). As It Was. Macmillan. ISBN 0-330-42705-9.

- Waters, Chris (2011). Fred Trueman: The Authorised Biography. London: Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-453-2.

External links

Media related to Freddie Brown (cricketer) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Freddie Brown (cricketer) at Wikimedia Commons- Freddie Brown at ESPNcricinfo