French rule in the Ionian Islands (1797–1799)

The first period of French rule in the Ionian Islands (Greek: Πρώτη Γαλλοκρατία των Επτανήσων, romanized: Próti Gallokratía ton Eptaníson) lasted from June 1797 to March 1799. Following the fall of the Republic of Venice in May 1797, the Ionian Islands, a Venetian possession, were occupied by Revolutionary France. The French instituted a new, democratic regime and, following the Treaty of Campo Formio, annexed the islands to France, forming the three departments of Corcyre (Corfu), Ithaque (Ithaca) and Mer-Égée (Aegean Sea).

| French rule in the Ionian Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overseas departments of the French First Republic | |||||||||

| 1797–1799 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

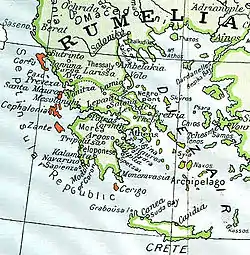

Map of the Ionian Islands ("Septinsular Republic") in orange, in 1801; Ottoman territory in green | |||||||||

| Capital | Corfu | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| Government | |||||||||

| • Type | Republic | ||||||||

| Commissioner-general | |||||||||

• June 1797 – January 1798 | Antoine Gentili | ||||||||

• January–August 1798 | Pierre-Jacques Bonhomme de Comeyras | ||||||||

• October 1798 – March 1799 | François Louis Dubois | ||||||||

| Historical era | French Revolutionary Wars | ||||||||

| 12 May 1797 | |||||||||

• French occupation of Corfu | 28 June 1797 | ||||||||

| 17 October 1797 | |||||||||

| 3 March 1799 | |||||||||

| 2 April 1800 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Greece | ||||||||

Originally widely welcomed, French rule began to grow oppressive to the islanders, and aroused the enmity of the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire. In 1798, a joint Russo-Ottoman campaign was launched against the islands, culminating in the four-month siege of Corfu. Its fall in March 1799 signalled the end of French rule, and the islands were reorganized as the Russo-Ottoman protectorate of the Septinsular Republic. The islands were again annexed to France in 1807 after the Treaty of Tilsit, but retained many of the institutions of the Septinsular Republic. The French were evicted from most of the islands by the British in 1809–10; only Corfu resisted until 1814. In 1815, the British established the United States of the Ionian Islands.

Background

At the end of the 18th century, the Ionian Islands (Corfu, Zakynthos, Cephalonia, Lefkada, Ithaca, and Kythira) along with a handful of exclaves on the Epirote mainland, namely the coastal towns of Parga, Preveza, Vonitsa, and Butrint, were the sole remaining overseas possessions of the once mighty Republic of Venice in the East.[1] In 1795, the Islands' population was counted as 152,722.[2]

Under Venetian rule, the society of the Ionian Islands was divided into three classes, analogous to those of Venice itself: the privileged nobility, the urban middle class (cittadini) and the commoners (popolari).[3] The noble families, who enjoyed full Venetian citizenship, were on top of the pyramid, and provided the members of the ruling council of each island. Originally restricted to Italian settler families, from the 16th century on this group also included Greek families. As in Venice, Corfu, Cephalonia, and Zakynthos each had a Libro d'Oro, where the aristocratic families were inscribed.[3] Their nature differed from island to island: in Corfu, they were obliged to reside in Corfu city; likewise in Kythira and Zakynthos they mostly dwelled in the capital, whereas in Cephalonia a rural nobility persisted, and no clear distinction was evident in Lefkada.[4] Nevertheless, the power of the nobility rested on the ownership of land, and as a class they derided mercantile activity, which was left to the urban burghers; as a result, the latter also came to amass wealth and land.[3] The burghers in turn challenged the nobility's claim to monopolize local authority and aspired to join the ruling class, while the peasantry was largely politically marginalized.[4]

The Venetian authorities were left in a position of mediator, but still had to acknowledge the power of the noble families, who often were a law on themselves and could even raise military corps of their own; while the nobles were content to pursue their private feuds and plot and conspire against each other for local office, they were also able of concerted action against the Venetian authorities, when they felt their interests threatened. Venetian writ ran lightly in the cities, and was almost non-existent in the countryside; not infrequently, Venetian official who ventured to the country to arrest some outlaw, were forced back in humiliation.[5] The Venetian regime was more concerned with maintaining its rule than providing efficient administration. Thus ten murders were punished with ten years in prison, while speaking ill of the Venetian governor—the provveditore generale da Mar—was punished with twenty. Out of a mix of governmental ineffectiveness and deliberate policy, the bulk of the local populace was kept in a state of ignorance: there were no printing presses or schools, and the majority of the population was illiterate. Only the privileged classes, who could send their sons to study abroad, had access to higher education.[6] As the medievalist William Miller remarked, "If the Corfiotes of that day seemed [...] to be ignorant and superstitious, poor and indolent, they were what Venice had made them".[7]

A further distinguishing feature between rulers and ruled was religion, where the official Roman Catholicism of the Venetian authorities was opposed by the popular Greek Orthodox identity, expressed in the veneration of each island's saint or saints.[8] Increasingly during the 18th century, Orthodoxy also provided a link to a rising European power, the Russian Empire. A pro-Russian current emerged, and several Islanders entered Russian service, especially during Catherine the Great's "Greek Project".[9] Disregarding Venetian neutrality, many Isladers, including nobles, participated in attempts to provoke a Greek uprising against Ottoman rule, such as the Orlov Revolt or the raids of Lambros Katsonis and Andreas Verousis.[9][10] Others, especially from Cephalonia, settled in the Crimea, recently conquered by the Russian Empire.[11] Nevertheless, support for the Venetian regime was still widespread enough that when the new provveditore generale, Carlo Aurelio Widmann, arrived in 1795, he could rely on the assistance of the local communes, leading nobles, the Jewish community of Corfu, and both Orthodox and Catholic clergy, to raise the necessary funds to pay for the garrisons and administrative personnel.[12][13] This also shows the parlous state of Venetian defences of the Islands at that time, crippled by lack of money, interest, and supplies from the metropole.[13]

As the French Revolutionary Wars erupted into northern Italy, Venice was shaken to its core: the spread of radical Jacobin ideals among her subjects, the undisguised hostility of the victorious French armies to the ancient aristocratic republic, and the dismal state of Venetian finances and military preparedness led to the gradual erosion of Venetian rule in its mainland possessions (Terraferma), and the eventual Fall of the Republic of Venice to Napoleon Bonaparte in May 1797.[1] In the Ionian Islands, the news of the French advance into Lombardy in 1796 led Widmann to take extraordinary measures to strengthen the defence of the Islands, even investing his own private fortune for the cause.[14][15] French agents were already active in the islands, most notably the French consul in Zakynthos, the merchant Constantine Guys, who not only fomented anti-Venetian feeling, but was suspected of orchestrating the arson of his own consulate on 29 October, an event that was used by Napoleon as one of the pretexts for his declaration of war against Venice.[14] Rumours of the self-abolition of the Great Council of Venice on 12 May spread quickly to the islands. While pro-French elements (the karmanioloi) were instructed by Guys on the meaning of concepts like "liberty" and "equality", many nobles mobilized against them, with proposals were made to kill all French sympathizers. Despite such agitation, order was kept, and the definite news of the political change in the metropolis, with the establishment of a new, republican Provisional Municipality of Venice, in early June, was met with calm and restraint.[14]

Start of the French occupation

The fate of Venice and of its possessions was to be decided between France and Austria. No mention of the Ionian Islands was made in the Preliminaries of Leoben. The two sides had different objectives: the Austrians wanted to keep the French out, and welcomed the possibility that the islands would come under the rump Venetian Republic envisaged at Leoben, as a buffer between French and Austrian territories in the Adriatic; whereas for Napoleon the islands were a critical stepping-stone for his ambitions in the Eastern Mediterranean, which would soon lead to his invasion of Egypt.[16][17] As the French diplomat Jacques Baeyens notes, the whole "Ionian adventure" was a personal project for Napoleon, who consulted nobody, least of all the ruling French Directory, before sending French troops to occupy the islands.[18] The Islands were to be

Consequently, on 26 May, Napoleon ordered his fellow Corsican, the général de division Antoine Gentili, to begin preparations for a military occupation of the Ionian Islands. A mixed Franco-Venetian fleet with 3,159 men sailed on 13 June from Malamocco. The ships flew the Venetian flag of St. Mark, since Gentili was ostensibly merely the representative of the new, pro-French Provisional Municipality of Venice, and the expedition intended to avoid possible secession of the colony from the metropolis. In reality, Napoleon instructed Gentili to encourage the local inhabitants to pursue independence, by reminding them of the glories of Ancient Greece; the scholar Antoine-Vincent Arnault was sent along as observer for Napoleon and a political advisor and propagandist.[19]

In the meantime, commissioners from the Provisional Municipality of Venice arrived in Corfu, informing Widmann of events and bringing orders to maintain order and begin the democratization of the local administration. Widmann tried to ensure consensus by issuing a notarized declaration of public concord, but only 177 citizens, of whom 71 nobles, signed it.[19] The French fleet arrived on 27 June, and the French troops disembarked on the next day, amidst tumultuous reception by the local populace, led by the Orthodox primate (protopapas), Georgios Chalikiopoulos Mantzaros, who gifted Gentili with a copy of Homer's Odyssey; the nobility reacted to Gentili's proclamation, on 29 June, that the French brought liberty to the Islands with reserve and suspicion.[19] Nevertheless, with the support of the populace and the resigned stance of the Venetian authorities, the imposition of French rule was rapidly accomplished not only on Corfu, but on the other islands as well. The only resistance was provided by some elements of the Venetian garrison troops, but these were quickly disarmed and disbanded; only the volunteer companies at the exposed possessions of Butrinto, Parga, Lefkada, and Kythira, as well as the armatoloi troops in Preveza and Vonitsa, were retained in French pay.[19] Although Widmann nominally remained the head of the administration, actual power lay with Gentili.[20] When Venetian commissioners arrived bearing 60,000 ducats for the payment of army and fleet and the loans Widmann had contracted, the money was simply confiscated by the French.[19]

The Austrian court protested the unilateral French occupation, but could do little about it. In the ongoing negotiations, Napoleon for a while pretended that the islands were to be incorporated into the Cisalpine Republic, but in the end, Austria was forced to accept the fait accompli to secure her own control over Dalmatia from the spoils of the Venetian state.[21]

Establishment of a democratic regime

As in the Venetian metropolis, the French established new administrations in the form of Provisional Municipalities. In Corfu, the body comprised the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Corfu, Francisco Fenzi, the protopapas Mantzaros, a Catholic and an Orthodox priest, two Jews, six nobles, ten burghers, two craftsmen and six peasants. Widmann was appointed to chair the body, but he resigned during its first session, and was replaced by the Corfiot noble Spyridon Georgios Theotokis. The nobles tried to mobilize anti-Jewish sentiment against the council, and a riot broke out on its second session on 28 June, but was suppressed.[19][22]

With Arnault as its political advisor, the Provisional Municipality of Corfu became the supreme executive authority on the island. Its chairman and vice-chairman were elected by secret ballot among its members for terms of one month. Sessions of the council were opened to the public (but confined to 40 attendees); closed sessions could be held to discuss a subject, but all decision-making had to be public, and every citizen could request to speak during these sessions.[19] Eight committees (comitati) were created for Public Salvation, Health, Food, Commerce and the Arts, Economy, Police, Public Education, and Military Affairs. These committees exercised administration in their respective fields and could propose laws and select their officials, but their approval was the purview of the Provisional Municipality council.[19]

Justice was reformed wholesale, with the introduction of French legal principles and the establishment of civil courts—seven county courts, two courts of first instance, and a court of appeal—and criminal courts—two magistrate's courts and an appeals court.[19] Unlike Venetian times, when judges were chosen by the heads of the noble families, now the judges were appointed by the Provisional Municipality, which had also the right to issue pardons.[19][23] A similar pattern was followed in the other islands, with the notable exception of Cephalonia, which traditionally had been divided into multiple provinces; now no less than five Provisional Municipalities were established on the island, at Argostoli, Livatho, the Castle of Saint George, Asos, and Lixouri.[19]

On 5 July, in an official ceremony, the liberty tree was planted in the main square of Corfu city, while the flag of St. Mark was thrown into a pyre, to be replaced by the French tricolour. On the next day, the Provisional Municipality of Corfu ordered the Libro d'Oro, the emblems of the Venetian Republic, the patents of nobility and coats of arms of the noble families to be likewise destroyed. This provoked the reaction of the nobles, who destroyed the liberty tree. Although a bounty of 500 thaler was placed on the unknown perpetrators, they were never found.[19] Similar events spread across the islands: at Zakynthos, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Cephalonia and Zakynthos, Francesco Antonio Mercati and the Greek Orthodox protopapas, Gerasimos Soumakis, led the ceremony of planting the tree of liberty on 23 July; at Cephalonia, Jacobin clubs were established, and proposed the abolition of Christianity and the restoration of Ancient Greek religion and of the Olympic Games; everywhere the burning of the Libro d'Oro and the symbols of nobility was accompanied by festivities by the populace.[24] In Zakynthos, the more established presence of pro-French and Jacobin-influenced elements led to some violence against the nobility, but elsewhere the new regime took power mostly peacefully, and proceeded to reform society and administration; following the abolition of the nobility's privileges, proposals were made for debt relief, and a land reform involving the feudal lands, increasing the competences of local government, etc.[25]

The French revolutionary songs Carmagnole and the Marseillaise, in their original lyrics or in various translations and adaptations, traditional Greek revolutionary songs, and the works of Rigas Feraios and the democratic Zakynthian poet Antonios Martelaos, enjoyed great popularity.[24] For the first time, extensive use of the Greek language was made in public documents, which were headed with the words "Liberty" and "Equality", and dated, in imitation of the French Revolutionary calendar, as the "First Year of Greek Liberty" (Χρόνος πρῶτος τῆς Ἐλευθερίας τῶν Γραικῶν). The new political and administrative reality also demanded that new terms were invented, and thus introduced into the modern Greek language along with the ideas of the French Revolution.[24] All these events signified a complete break from the Venetian regime. The Provisional Municipality of Venice was left to lodge a formal but ineffective protest, on 4 August, to the French ambassador, Lallemant.[24]

In August, Gentili began a 40-day tour of the Islands, confirming the firm installation of the new regime,[24] but Arnault resigned on 29 July.[26] The lawyer Pierre-Jacques Bonhomme de Comeyras was appointed as his successor on 7 January 1798. He did not immediately come to the Islands, however; informed of the bad state of public finances, he toured Italy for several months trying to secure funds, mostly in vain, until he succeeded in concluding a 500,000-franc loan with the Republic of Ragusa.[27][28]

Annexation to France

The pro-French elements in Zakynthos soon sent emissaries to Napoleon for an outright annexation of the Islands to France. In Corfu, the pro-Venetian tendency initially prevailed in the Provisional Municipality, hoping to be included in a reorganized Venetian state. Eventually, however, the pro-French faction won out, particularly after attempts to get Austria to intervene in Corfu failed to elicit any response; on 5 October Napoleon declared himself ready to cede Venice itself to the Austrians, but was determined to keep the Ionian Islands. The pro-French faction eventually prevailed in Lefkada as well, while Cephalonia remained divided, and Preveza pro-Venetian.[29] Finally, in the Treaty of Campo Formio of 17 October, the last vestiges of the Republic of Venice were swept away. According to its provisions, Austria annexed most of the mainland domains of Venice, including the city itself. The Ionian Islands, the "most valuable part of Venice" according to French Foreign Minister Talleyrand, were left to the "full sovereignty" of France.[24] Very quickly, the Provisional Municipalities of the islands petitioned Napoleon to annex the islands outright, and Gentili's reports to Napoleon also indicated that the population was favourable to a full integration with the French Republic. On 1 November Napoleon's stepson Eugène de Beauharnais arrived at Corfu, and on the same day announced to the Provisional Municipality the terms of the Treaty of Campo Formio, and the annexation of the islands to France. The news was received with great enthusiasm by the council, which awarded Eugene with a sword, and voted to send a delegation to convey its gratitude to Napoleon.[30]

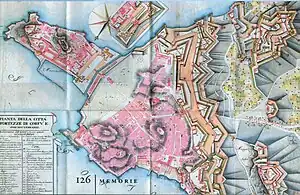

On 7 November, Napoleon issued a decree creating the departments (départements in French, πολιτομερίδια in Greek) of Corcyre, Ithaque, and Mer-Égée. Corcyre comprised the island of Corfu and its neighbouring island groups, and the mainland exclaves of Butrint and Parga; Ithaque comprised Lefkada, Ithaca, Cephalonia and other minor islands, as well as Preveza and Vonitsa on the mainland; Mer-Égée comprised Zakynthos, Kythira and Antikythira, and other minor islands.[31] Each department was run by a five-member committee (commission départementale) and its administration was divided into twelve sections (Commerce and Arts, Police, Gambling, Theatre, National Guard, Waters and Cisterns, Public Buildings, Military Lodgings, Furniture and Food Provisions, Health and Prisons, Public and Private Schools, Mores and Religions).[32] Each department was further subdivided into cantons with a municipal committee for each (five-member for cantons under 5,000 residents, seven-member for above). Cities were also divided into cantons, which received new names evocative of the new ethos: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, France, Greece, Commerce, etc.[27] A French commissioner, who had to sign off on all decisions, was assigned to each department; a commissioner-general of the Directory was established at Corfu, a post provisionally occupied by Gentili. In turn, each department was to send a representative to the Directory in Paris. As an integral part of the French Republic, the French Constitution of 1795 was applied across the islands, and all Ionian public authorities and vessels were to be issued with French insignia and passports.[27] The defence of the new French possession was assumed by the Division du Levant, whose commanding general was also the supreme police authority, and a naval squadron of ten ships.[27]

Due to a sudden illness, Gentili had to return to Corsica to recuperate, where he died almost immediately. As his replacement, the Directory briefly envisaged the distinguished general and future King of Sweden, Jean Bernadotte; but in the event, the général de division Louis François Jean Chabot was chosen.[27][33] The new commissioner-general, Comeyras, did not arrive in Corfu until 28 July 1798, and immediately engaged in the reorganization of the islands' administration with much energy.[34][35] His tenure proved brief, however, as barely a month later he was recalled and replaced with François Louis Dubois. Among his achievements were the establishment of a five-man team of legal experts to revise the appeals process, and of three gendarmerie companies to provide police services. Comeyras left Corfu in early September, before his successor arrived; he died at Ancona of an epidemic.[34]

Among the beneficial measures of the French authorities were the great care shown to public health and education. The public school system—which was partly funded by secularizing Catholic Church property—was expanded and French-language public schools founded. A "National Library" was opened in May, and a "National Printing Office" under the Frenchman Jouenne on 11 August. The French also planned to establish further printing presses, send children to France for education, and create a regular shipping route to Italy.[27]

Reactions to French rule: From enthusiasm to disenchantment

The French occupation of the Islands gave rise to hopes among Greek emigrants and intellectuals in Western Europe that they could be used as a springboard for a liberation of Greece. In July 1797, Rigas Feraios published his Constitution of the Hellenic Republic, based on the French revolutionary constitutions of 1793 and 1795.[36] For a time Napoleon appeared receptive to proposals of a Greek uprising, and entertained contacts with the Maniots in southern Greece, Ali Pasha of Yanina, and Ibrahim Pasha of Scutari. He even sent the Corsican Greek military officer Demetrio Stefanopoli as his envoy to the Ionian Islands and Mani, who on his return in 1798 openly spoke of a restored Byzantine Empire and "Franco-Greek liberty" up to the Bosporus. At the same time, in Ancona, an "Executive Directory for the Commerce of Corsica, Malta, Zakynthos, Cephalonia, Corfu, the French Isles of the Adriatic, the Archipelago, and Egypt" was established with Greek and French members, aiming to collect intelligence and foment insurrection. In the event these machinations came to nothing, once the French were committed to the invasion of Egypt, rather than the Balkan provinces of the Ottoman Empire.[37]

While initially enjoying broad support, the French regime soon began to loose some of its appeal. The heavy taxation and strict fiscal administration were widely resented, while the dismissive attitude of the French towards religion and the traditions of the Ionian people, coupled with the predatory behaviour of French troops, made them increasingly unpopular.[27] The quartering of troops among the Corfiot citizenry—a necessity due to the complete lack of barracks—was also greatly resented.[38]

Although the Greek clergy had supported the installation of the democratic regime and even participated actively in it, the French generally treated the clergy with hostility, as can be seen by their demand that all clerics wear the tricolour revolutionary cockade on pain of execution.[27][39] The nobles were opposed to the French from the outset, and maintained contacts with Austria, never losing the opportunity to foment popular resentment, but even the new democratic clubs like the "Patriotic Society" and the "Constitutional Club", making full use of the very liberty granted by the French, began criticizing Gentili and questioning the necessity of French presence in the Ionian Islands; the Constitutional Club was eventually closed by the French authorities.[27]

French diplomatic manoeuvring, notably the cession of Venice to Austria, also estranged parts of the populace: in December 1797, rumours began circulating that the same fate awaited the Ionian Islands, with the mainland exclaves to be sold to the Ottomans. Chabot intervened forcefully to quell the rumours, and expelled the Catholic archbishop Francisco Fenzi, who was considered as the instigator of the rumours, on 11 April 1798.[27][39] Conversely, the news of the French occupation of Malta and Alexandria, as part of Napoleon's invasion of the Ottoman territories in the Levant, were received with enthusiasm.[39][40]

French relations with Ali Pasha

The main external concern of the French administration was its relationship to its most important neighbour, the powerful and ambitious Ali Pasha of Yanina, semi-autonomous Ottoman ruler of much of Albania and mainland Greece. Already on 1 June 1797, Ali Pasha himself had taken the initiative, sending a letter to Napoleon expressing his respect and admiration, hopes of friendly relations, and the dispatch of four French artillery NCOs to train the Pasha's own artillery. Both Napoleon and the Directory received this with favour, and instructed Gentili to establish amicable relations with the ruler of Yanina.[34]

Gentili met in person with Ali at Butrint during his tour of the islands, and French envoys, notably adjudant-général Roze, were frequent visitors at his court in Yanina. Roze was even wed to an adopted daughter of Ali's. Ali managed to convince the French of his good intentions, showering them with honours and providing food—and even feigning interest in Jacobin ideals—but his main objective, the cession of the mainland exclaves of the Ionian Islands, was rebuffed. Gentili did, however, lift the prohibition on Ottoman ships from traversing the Straits of Corfu, which had been in place since the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz. This allowed Ali to move over sea against his rival, Mustafa Pasha of Delvino. In July/August 1797 (or in Easter 1798, according to other sources), his forces sailed to Lukovo and committed massacres against the local population, forcing them to submit to Ali's authority.[34]

Relations became strained in 1798, after Ali received orders from the Sultan to provide troops for a campaign against another powerful regional ruler, the pasha of Vidin, Osman Pazvantoğlu. Chabot sent his adjutant, Schaeffer, ostensibly to demarcate the boundaries at Butrint, but in reality to dissuade Ali from obeying, as the French had good relations with Pazvantoğlu. Ali Pasha used the opportunity to complain of the lack of reciprocation for his friendly gestures, and claimed that only if the French provided him with 10,000 troops and 100,000 sequins would he be able to disobey the Sultan.[34] In mid-June, Napoleon's aide-de-camp, Lavalette, arrived in the Islands, bearing news of the capture of Malta and a letter from Napoleon to Ali Pasha, urging him to put faith in Lavalette and in turn send a trusted envoy of his own to Napoleon. As Ali was absent in the campaign against Pazvantoğlu, Lavalette was unable to hand over the letter.[34] In reality, Napoleon's invasion of Egypt caused Ali deep concern about ultimate French designs. While the French authorities in the Islands believed in Ali's friendship and considered that his domains shielded them from attack by the Sultan's forces, Ali decided to side with the Sultan, particularly after news of the French defeat in the Battle of the Nile arrived. In preparation for the inevitable conflict, the ruler of Yanina patched up his differences with all neighbouring rulers and magnates, as with the Souliotes.[34]

Russo-Ottoman conquest of the Ionian Islands

The French invasion of Egypt had upset the balance of power in the East, and caused a rapprochement between the Ottomans and the Russian Empire, who concluded an alliance in July 1798 (although the official treaty was delayed until January 1799).[41] As the joint Russo-Ottoman fleet set sail for the Ionian Islands, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory V sent a missive to the clergy and people of the Islands, denouncing the impious and godless French, urging the inhabitants to drive them off, and assuring them that the Sublime Porte would allow them to choose their own form of government, on the model of the Republic of Ragusa. The same assurances were repeated in a proclamation by the head of the Russian fleet, Fyodor Ushakov, who also emphasized that the joint fleets were operating to liberate the Islanders from the "heathen French".[41] The French fought back in the propaganda war, with pamphlets like the To the Rhomaioi of Greece by the Greek Konstantinos Stamatis and Emile Gaudin's Reflections of a Philhellene (translated into Greek by Stamatis) being printed and circulated in large numbers.[41]

Ali Pasha's attacks on Butrint and Preveza

Chabot, the military governor of the Islands, received news of the Russo-Ottoman declaration of war on France on 3 October 1798, at Lixouri.[34] At this time, Ali Pasha's forces had already assembled in the settlements around Butrint. Biding his time, Ali invited adjudant-général Roze for negotiations to Filiates, but once he had learned as much as he could about French strength and dispositions at Corfu and elsewhere, he ordered him taken prisoner to Yanina. Ali tried to repeat the same stratagem with the commandant of Butrint, but he sent only Lieutenant Steil and a Greek priest; both were arrested and brought to Yanina.[42] Ali composed a letter to Chabot, demanding the cession of the mainland exclaves, as well as the Castle of Santa Maura on Lefkada. A second letter followed soon after, where he demanded the surrender of Corfu itself.[41] The new commissioner-general, Dubois, arrived at about the same time, and on 13 October issued a proclamation to the inhabitants of the three departments.[41]

During the following days, the commandant of Butrint reported that Ali's troops were moving to occupy the heights around the town, and asked for reinforcements. The attack began on 18 October. Chabot sent général de brigade Nicolas Grégoire Aulmont de Verrières with 300 men, and came himself to supervise the defence. Unable to withstand the vastly larger numbers of Ali's troops, on 25 October the French blew up the fortifications and evacuated to Corfu, along with the Greek inhabitants of the town and its environs.[41]

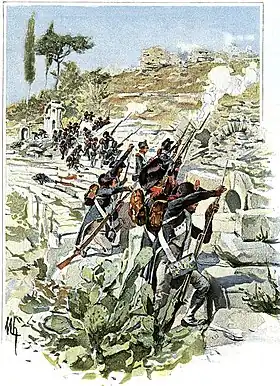

At the same time, Ali's forces moved on Preveza. There the French, anticipating an attack, had begun erecting fieldworks at the isthmus leading to the town, at the site of ancient Nicopolis. On 22 October Ali himself, accompanied by his son Mukhtar and some 4,000 foot and 3,000 horse, appeared. The French, under général de brigade Jean Jacques Bernardin Colaud de La Salcette, could muster only 440 French regulars, 200 militiamen, and 60 Souliotes. The ensuing Battle of Nicopolis was extremely bloody, with most of the French troops killed or captured, the latter including La Salcette. After capturing Preveza, Ali had the pro-French inhabitants publicly executed, and torched the town. Using the unsuspecting Metropolitan of Arta, Ali then lured the Prevezans who had fled to Aktion to return, and had them too beheaded. The French prisoners were subjected to torture, and those who survived were sent to Constantinople.[41] Vonitsa too surrendered afterwards, and only Parga was left to resist Ali's forces.[41] General Chabot tried to enlist Mustafa Pasha of Delvino against Ali Pasha, but failed.[43]

Operations of the Russo-Ottoman fleet

The Russo-Ottoman fleet arrived at Kythira on 7 October 1797. The French garrison, 68 strong under Captain Michel, refused repeated offers of surrender. After naval bombardment and attacks by Ottoman infantry, on 13 October the French agreed to surrender the island's fort under terms.[44] From Kythira the fleet sailed to Zakynthos via Koroni. On Zakynthos, the French position was precarious. The nobles on the island were joined by a large pro-Russian faction, while leading members of the French administration were missing at this crucial moment: commissioner Chriseuil de Rulhière was in Paris, the head of the administration was in Corfu for consultations, and general La Salcette was in Lefkada and then Preveza. The burden of defending the island fell on Major Vernier, who disposed of 400 French soldiers and 500 militia.[44] The fleet appeared off the island on 24 October. While many of the inhabitants of Zakynthos town fled to the interior in fear of bombardment, large numbers of peasants, bearing Russian flags, streamed into the town to prevent the French and their supporters from providing any resistance. The latter were forced to retreat behind the walls of the citadel, while the peasants opened the jails, looted the administrative buildings, and burned the tree of liberty along with all official documents at the Square of St. Mark's. The looting spread to the houses of individual pro-democratic citizens, as well as to the Jewish quarter.[44] A delegation of nobles, led by Count Nikolaos Gradenigos Sgouros and the protopapas Soumakis went to Ushakov to offer the capitulation of the island. A detachment of 700 Russians, along with a few Turks, landed on the island and joined the mass assembled in the town, laying siege to the citadel. The French garrison surrendered on 25 October. Vernier and 54 others were left free to return to France, while the rest were moved to Glarentza as prisoners of war, before being shipped to Constantinople.[44]

.jpg.webp)

The next target of the Russo-Ottoman fleet was Cephalonia. As in Zakynthos, there too a broad pro-Russian movement, fanned by Russian agents, the clergy, and the nobility, had come into existence. The French under Captain Royer disposed of no more than 350 men, who had to defend the island's two major towns, Argostoli and Lixouri. Given that both were completely unfortified, and amidst daily growing and more blatant hostility by the population, the French decided to withdraw to the Assos Castle, and thence evacuate to Lefkada.[44] Upon their departure from Argostoli, the inhabitants, joined by armed peasants, tore down the French flag and hoisted the Russian one instead. Amidst rioting and violence, the democratic regime was abolished. When the Russo-Ottoman fleet arrived on 29 October, the island was no longer under French control. The French garrison of Lixouri successfully evaded to Lefkada, but was taken captive by armed peasants, while those of Argostoli managed to reach Assos only to surrender to the Russians, and be in turn transported to Constantinople.[44] In Ithaca, the local inhabitants convinced the French garrison, under Captain Millet, that resistance was futile, and urged them to withdraw to Corfu. Unlike the other islands, the withdrawal of the French took place in an orderly and friendly atmosphere. When Ushakov sent two of his ships to the island, the inhabitants submitted.[44]

In Lefkada, the anti-French agitation had also had a profound effect; the local authorities informed the French that they could not count on the support of the populace, which was rapidly arming itself, against the Russians. The French, under Major Mialet, withdrew to the Castle of Santa Maura. Reinforced by the garrison of Vonitsa, and some remnants of the garrison of Preveza, he disposed of about 500 men.[45] On 28 October, the Russian flag was hoisted in the town hall, and remained there despite French threats to the inhabitants. A squadron of the Russo-Ottoman fleet arrived soon after, and after the refusal of the French to surrender, began to besiege the fortress. Eventually the rest of the fleet under Ushakov arrived, and after several days of close blockade and bombardment, the French surrendered on 17 November. Ushakov allowed 20 French officers to depart for France immediately, but the rest were sent to captivity in Constantinople.[43]

Siege and fall of Corfu

With the fall of Lefkada, Corfu remained as the last bastion of French control in the Ionian Islands. There too, the anti-French and pro-Russian sentiment had been gaining ground, and the exhortations of commissioner-general Dubois largely failed to have an impact. French forces on the island, augmented by the garrisons of Ithaca and Parga, amounted to 1,500 infantry and some 300 artillerymen, as well as 8 naval vessels.[43] To augment this force, on 23 October martial law was declared and a militia formed, followed by compulsory levies from the wealthy and confiscations of food and animals. On 2 November, the inhabitants of Corfu city were disarmed, but when the French tried to repeat this at the suburb of Mantouki the next day, they met violent resistance, leading to the bombardment and evacuation of the suburb, and the looting of the Platytera Monastery. The rest of the suburbs were disarmed without major incident. Preparations for a siege also included the levelling of the quarter of Sano Rocco at the main entrance to the city, and the fortification of the island of Vido.[43]

The first enemy ships arrived off the city on 5 November, landing troops north and south of the city. Russian offers for a capitulation, including the immediate transfer of the garrison to a French port, were rejected. Hostilities began on 9 November with skirmishes between the two sides. On 19 November, Ushakov arrived from Lefkada with the remainder of the fleet. His main priority was to restore order to the island, where the collapse of French authority had unleashed an orgy of looting, murder, and arson. Count Nikolettos Voulgaris was appointed to head the civil administration, while the peasantry was organized to support the siege.[46] The Russo-Ottoman forces were further augmented by 3,000 Albanians sent by Ali Pasha, while on the French side volunteer detachments from Corfu and Cephalonia distinguished themselves. On 3 February 1799, three French ships managed to break the blockade and went to Ancona, carrying pleas for reinforcements—as well as art objects looted from Corfu—but the reinforcements never arrived. The capture of Vido island on 1 March 1799 signalled the beginning of the end for the besieged, and the garrison capitulated on 4 March, on condition that the French troops be repatriated immediately.[47]

Aftermath

In all the islands they occupied, the Russians installed provisional administrations of nobles and burghers. Very soon, the Russian authorities invited assemblies of the nobles to undertake the governance of the Ionian Islands, thereby restoring the previous status quo.[47] On 6 May, the commanders of the two fleets announced that the Ionian Islands would comprise a unitary state, governed by a Senate (Γερουσία) in Corfu city, composed of three representatives each from Corfu, Cephalonia, and Zakynthos, two from Lefkada, and one each from Ithaca, Kythira, and Paxoi. The Venetian nobleman Angelo Orio, the last Venetian provveditore of Argostoli, was appointed head of the Senate, and entrusted with the creation of a constitution for the new state.[47] Orio's constitution envisaged a thoroughly aristocratic regime, with each island headed by a Great Council composed of the nobles and the upper bourgeoisie. The Great Councils would elected the senators. Each island would retain a local administration and a treasury, but a central treasury would exist in Corfu. The Senate was the ultimate executive authority, and its chairman the head of state. A Minor Council of 40 would be elected by the Great Councils of the three largest islands, and would be responsible for justice, the selection of officials, and advising on legislation.[47] On 21 June, at Ushakov's instigation, a Greek Orthodox archbishopric was re-established on the islands as the Metropolis of Corfu. The aged protopapas Mantzaros elected to fill the post, but died before he could be consecrated. A heated and protracted struggle between the priest Petros Voulgaris and the scholar and former archbishop of Kherson and Astrakhan, Nikiforos Theotokis, followed, but with Ushakov's intervention the new see was finally filled with the election of the Ierotheos Kigalas on 19 February 1800.[48]

On 21 June 1799, the Senate decided to send a twelve-member delegation to Constantinople and Saint Petersburg to express its gratitude to the Sultan and Tsar, but also press for the restoration of the Islands' maritime and land frontier with the withdrawal of Ali Pasha from Butrint, Preveza, and Vonitsa, and their recognition as an independent state. As Angelo Orio participated in the delegation, he was replaced as head of the Senate by Spyridon Theotokis. Once in Constantinople, however, the delegation quickly realized that the Porte was not interested in recognizing the Islands' independence, but rather in creating a vassal state under Ottoman suzerainty. At the suggestion of the Russian ambassador, Vasily Tomara, the delegation submitted a memorandum to the other ambassadors, requesting the recognition of the Islands as an independent and federal state, under the protection of the European powers. Two of the delegates, the Corfiot Count Antonio Maria Capodistrias and the Zakynthian Count Nikolaos Gradenigos Sigouros Desyllas remained in Constantinople to conduct negotiations with the Porte, while Orio and another delegate, Kladas, were to represent the Ionian cause in Saint Petersburg.[49] The negotiations between Russia, the Porte, and the Islands, led to the signing of the Treaty of Constantinople on 2 April 1800, which created the Septinsular Republic, under joint Russian and Ottoman protection.[50]

The new state proved politically unstable, but retained its precarious autonomy. The islands remained de facto under Russian influence and military protection, becoming thus involved in the Russian conflicts with France and Ali Pasha. The Septinsular Republic survived until 1807, when the Treaty of Tilsit once again surrendered the islands to France.[51] While the Republic was abolished, its constitution and forms of governance were retained during this second period of French rule. The renewed French presence in the area aroused the opposition of the British, who instigated a naval blockade of the islands. In October 1809, British forces easily took Zakynthos, Cephalonia, Ithaca, and Kythira, followed by Lefkada in April 1810. Only Corfu, Parga, and Paxoi held out, amidst a deteriorating supply situation, until the 1814 and the resignation of Napoleon. The Islands then passed under British control, and were formed into the United States of the Ionian Islands in 1815.[52]

References

- Moschonas 1975, p. 382.

- Miller 1903, p. 237.

- Mackridge 2014, p. 3.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 153.

- Karapidakis 2003, pp. 154–155.

- Baeyens 1973, pp. 15–16.

- Miller 1903, p. 238.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 155.

- Karapidakis 2003, pp. 155–156.

- Miller 1903, pp. 236–237.

- Miller 1903, p. 236.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 156.

- Miller 1903, pp. 238–239.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 157.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 382–383.

- Heppner 1985, pp. 64–67.

- Tabet 1998, pp. 133, 138–140.

- Baeyens 1973, pp. 18–19, 59.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 383.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 158.

- Heppner 1985, pp. 66–67.

- Karapidakis 2003, pp. 158–159.

- Baeyens 1973, p. 25.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 385.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 159.

- Baeyens 1973, p. 26.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 387.

- Baeyens 1973, pp. 27–28, 30–31.

- Karapidakis 2003, pp. 159–160.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 385–386.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 386.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 386–387.

- Baeyens 1973, p. 29.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 388.

- Baeyens 1973, pp. 31–32.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 161.

- Karapidakis 2003, pp. 161–162.

- Baeyens 1973, p. 24.

- Karapidakis 2003, p. 162.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 387–388.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 389.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 388–389.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 391.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 390.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 390–391.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 391–392.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 392.

- Moschonas 1975, p. 393.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 392–393.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 393–394.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 394–399.

- Moschonas 1975, pp. 400–401.

Sources

- Baeyens, Jacques (1973). Les Français à Corfou, 1797–1799 et 1807–1814 [The French in Corfu, 1797–1799 and 1807–1814] (in French). Athens: Institut français d'Athènes. OCLC 2763024.

- Heppner, Harald (1985). "Österreichische Pläne zur Herrschaft über die Ionischen Inseln" [Austrian Plans for Rule over the Ionian Islands]. Balkan Studies (in German). 26 (1): 57–72. ISSN 2241-1674.

- Karapidakis, Nikos (2003). "Τα Επτάνησα: Ευρωπαϊκοί ανταγωνισμοί μετά την πτώση της Βενετίας" [The Heptanese: European rivalries after the fall of Venice]. Ιστορία του Νέου Ελληνισμού 1770–2000, Τόμος 1: Η Οθωμανική κυριαρχία, 1770–1821 [History of Modern Hellenism 1770–2000, Volume 1: Ottoman rule, 1770–1821] (in Greek). Athens: Ellinika Grammata. pp. 151–184. ISBN 960-406-540-8.

- Mackridge, Peter (2014). "Introduction". In Anthony Hirst; Patrick Sammon (eds.). The Ionian Islands: Aspects of their History and Culture. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-4438-6278-3.

- McKnight, James Lawrence (1965). Admiral Ushakov and the Ionian Republic: The Genesis of Russia's First Balkan Satellite (PhD thesis). University of Wisconsin, Madison. OCLC 47945614.

- Miller, William (1903). "The Ionian Islands under Venetian Rule". The English Historical Review. 18 (70): 209–239. doi:10.1093/ehr/XVIII.LXX.209. JSTOR 549461.

- Moschonas, Nikolaos (1975). "Τα Ιόνια Νησιά κατά την περίοδο 1797–1821" [The Ionian Islands in the period 1797–1821]. In Christopoulos, Georgios A. & Bastias, Ioannis K. (eds.). Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, Τόμος ΙΑ΄: Ο Ελληνισμός υπό ξένη κυριαρχία (περίοδος 1669 - 1821), Τουρκοκρατία - Λατινοκρατία [History of the Greek Nation, Volume XI: Hellenism under Foreign Rule (Period 1669 - 1821), Turkocracy – Latinocracy] (in Greek). Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. pp. 382–402. ISBN 978-960-213-100-8.

- Tabet, Xavier (1998). "Bonaparte, Venise et les îles ioniennes: de la politique territoriale à la géopolitique". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (in French). 57 (1): 131–141. doi:10.3406/camed.1998.1230.

Further reading

- Bellaire, J.P. (1805). Précis des opérations générales de la Division française du Levant [Precis of the general operations of the French division in the Levant] (in French). Paris: Magimel & Humbert.

- de Rulhière, Chriseuil (1800–1801). Essai sur les isles de Zante, de Cerigo, de Cérigotto et des Strophades, composant le département de la Mer-Égée [Essay on the islands of Zakynthos, of Kythira, of Antikythira and the Strofades, forming the department of Mer-Égée] (in French). Paris: Dessenne.

- Lacroix, Louis (1853). Les Îles de la Grèce [The Islands of Greece] (in French). Firmin Didot. p. 638.

- Lunzi, Ermanno (1860). Storia delle Isole Jonie sotto il reggimento dei Repubblicani Francesi [History of the Ionian Islands under the Regime of the French Republicans] (in Italian). Venice.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pauthier, G. (1863). Les Îles Ioniennes pendant l'occupation française et le protectorat anglais [The Ionian Islands during the French occupation and the English protectorate] (in French). Paris: Benjamin Duprat.

- Rodocanachi, Emmanuel (1899). Bonaparte et les îles Ioniennes. Un épisode des conquêtes de la République et du premier Empire (1797–1816) [Bonaparte and the Ionian Islands. An episode of the conquests of the Republic and the First Empire (1797–1816)] (in French). F. Alcan.