Frente de Liberación Homosexual

The Frente de Liberación Homosexual (Homosexual Liberation Front, sometimes abbreviated FLH) was a gay rights organization in Argentina.[1] Formed at a meeting of Nuestro Mundo in August 1971, the FLH eventually dissolved in 1976 as a result of severe repression after the 1976 Argentine coup d'état.

Two hooded FLH members pose for a photo published in an August 1972 magazine article. | |

| Abbreviation | FLH |

|---|---|

| Formation | August 1971 |

| Founded at | Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Dissolved | June 1976 |

| Merger of |

|

The FLH was made up of a variety of semi-autonomous groups that operated individually but maintained contact with one another through a non-hierarchical organizational structure, enabling coordination and collaboration on actions and documents. Many of these groups were on the far left, and expressed anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism along with their advocacy for LGBT rights, women's rights, and labor rights; a view of all forms of oppression as interconnected was a key aspect of the FLH overall.

In 1973 and 1974, a large section of the FLH led by Néstor Perlongher became involved in Peronism, over the objections of other FLH members who noted Juan Perón's past involvement in repression of homosexuals. Members of the group were present at the inauguration of Héctor José Cámpora in May 1973, and at the Ezeiza massacre in June of the same year. By the end of 1974, the FLH had entirely separated itself from Peronism after Perón once again became president and reinstated the "Morality Brigade" tasked with state repression of sexuality.

In September 1973, the FLH published 5,000 copies of a one-off newspaper titled Homosexuales. They subsequently published six issues of an underground magazine called Somos from December 1973 through January 1976. Somos included criticism of capitalism, patriarchy, and heteronormativity as well as utopian messaging about sexual freedom; as time passed it became less journalistic and more cultural, and began to include art and poetry.

After the death of Juan Perón in 1974, attacks on gay people by right-wing paramilitary groups became more frequent, causing FLH membership to drop from about a hundred to roughly a dozen people. José López Rega called for homosexuals to be exterminated, and police officers were ordered to "scare [them] off the streets". The FLH eventually dissolved in June 1976 as a result of severe political repression. Some members fled to Europe and to other countries in Latin America, and many others were tortured, disappeared, or murdered during the Dirty War.

Formation

According to Héctor Anabitarte, the FLH began during an afternoon meeting in August 1971 at the home of Pepe Bianco, an intellectual who disagreed with the idea of a movement for homosexual rights but nevertheless allowed his home to be used for meetings of Nuestro Mundo and translated their articles to English so they could be read by groups in North America. In the book Historia de la homosexualidad en Argentina, Osvaldo Bazán wrote that Bianco lived with his mother and that the meeting actually took place in the apartment of Blas Matamoro in Once. In the meeting, the group of Nuestro Mundo members was joined by a group of others, many of them university students who were studying the social sciences[2] at the University of Buenos Aires.[3] People who were present and would go on to be members of the FLH when it was created include Héctor Anabitarte, Blas Matamoro, Juan José Sebreli, Manuel Puig, and Juan José Hernández.[2] Néstor Perlongher, another member who joined the FLH by way of the student organization Eros,[4] would quickly become a core figure in the FLH.[5]

Structure and ideology

Soon after the formation of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual, the members removed their initial leadership, deciding instead on a non-hierarchical organization to avoid authoritarianism and have a structure that was not reminiscent of a patriarchical family.[2] Different groups within the FLH were semi-autonomous from each other,[6] operating individually but remaining in contact to facilitate the organization of joint actions and agree on the content of documents. Large informational meetings were held in private residences to provide information about the FLH; after a general explanation of the organization's political platform, people who became interested could join an "awareness group" called Alborada from which they could transfer to one of the other factions that made up the FLH.[7]

All groups in the FLH agreed to the Puntos Básicos de acuerdo del Frente de Liberación Homosexual ("Basic Points of Agreement of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual),[8] an agreement created in May 1972[9] which had an advanced view of homosexuality for its time.[8] The stipulations of the agreement included that "homosexuals are socially, culturally, morally and legally oppressed. They are ridiculed and marginalized, severely suffering the brutally imposed absurdity of the monogamous heterosexual society"[lower-alpha 1] and that "this oppression comes from a social system that considers reproduction as the sole objective of sex".[lower-alpha 2][8] Many FLH factions were on the far left, holding radical positions and espousing anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism along with their advocacy for LGBT rights, women's rights, and labor rights;[10] this view of all forms of oppression as interconnected was a key aspect of the FLH.[8][11] Marxism and feminism were core aspects of the political analysis of the FLH,[12] and homosexuality was therefore understood as subversive because it challenged patriarchy.[13] The Black Panther Party was among the inspirations of the FLH;[2] member Juan José Hernández provided the group with a publication by the Black Panthers which he had been sent by a friend in the United States, and the text was translated to Spanish by Pepe Bianco.[14]

The Frente de Liberación Homosexual was clandestine throughout its existence.[15] When the magazine Panorama interviewed two of its members in 1972, the two men wore ski masks that covered their faces[16] and explained that this and other secretive practices were due to the persecution they faced.[17]

Member groups

The Frente de Liberación Homosexual would come to include more than ten groups.[9] Nuestro Mundo, Eros, and Alborada were involved early, as were the Profesionales, a group of well-known writers.[7] Safo, which was made up of lesbians, joined after the FLH was created, as did Emmanuel, a group of Christians.[9] Two other religious groups joined, for a total of three: one Catholic, one Protestant, and one centered around Third-Worldism. Bandera Negra ("Black Flag") separated from Eros due to disagreement about anarchism and became an anarchist group within the FLH.[7]

There was tension between intellectualism and militantism within the FLH, particularly between the Profesionales and Eros. The Profesionales were older and more moderate, and members of that faction were publicly known due to their writing; member Juan José Sebreli argued that Eros' desire to take action was a disruption from the discussion of theory and ideas.[7]

Relationship with Peronism

Despite the anti-authoritarianism of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual, many members of the group became interested in the left wing of Peronism[18] during its rise in 1973. A large group of the younger FLH members, including Eros[19] and led by Nestor Perlongher, believed that a connection between Peronism and the FLH was a desirable possibility.[18] Another large faction within the FLH was distrustful of Peronism, in part because the first and second governments under Juan Perón had repressed homosexuals with more arrests and police raids than any other government in Argentine history.[19] Juan José Sebreli, a member of an FLH group called Triángulo Rosa ("pink triangle"), left the FLH because he did not agree that the FLH should form a connection with Peronism.[20]

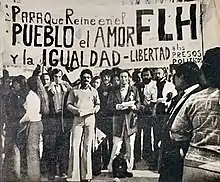

There was an FLH presence at the inauguration of Héctor José Cámpora in May 1973, where the group held a large banner with a slogan based on a lyric from the Peronist March: Para que reine en el pueblo el amor y la igualdad – Libertad a los presos políticos ("So that love and equality may reign among the people – freedom to the political prisoners").[18] After Cámpora became president, police repression of homosexuals essentially ceased for a two-month period, during which Peronism became more popular within the FLH and the pro-Peronist faction of the group gained more power. As a result, the FLH began dialogues with Peronist leaders and the government; the main focus of the FLH during this period was lobbying in an attempt to influence public policy.[19]

A group of FLH members was also present when Perón returned to Argentina on June 20, 1973, an event that would come to be known as the Ezeiza massacre; they handed out pamphlets signed by the FLH and Eros,[21] and carried a banner that proclaimed FLH support for both Peronism and Perón himself. However, there was not a full consensus within the FLH in favor of Peronism, nor was there one that members should be present in Ezeiza for the event.[22]

Left-wing Peronism and the revolutionary left as a whole were somewhat inaccessible to the FLH due to homophobia;[23] the left-wing consensus was that homosexuality was a counterrevolutionary product of moral degeneration under capitalism, and would fade away after the revolution along with issues like illiteracy and unemployment.[24] Marginalization by other left-wing organizations was a common complaint within the group,[12] and at both the Cámpora inauguration and the return of Perón, other groups that attended remained a few meters away from the FLH demonstrators on all sides.[21] Antonio Cafiero acknowledged in 2009 that gay people had not been wanted as part of the Justicialist Party during the time of the FLH, and FLH activists reported having met with advisers of Héctor José Cámpora who told them that homosexuals could be cured in rehabilitation camps when Cámpora took power.[23][24]

Members of the FLH expressed affinity with left-wing Peronism in an interview with the magazine Así, which was published in the July 1973 issue. Colonel Jorge Osinde used this association to discredit the left-wing Peronist organizations Peronist Youth and Montoneros, putting up posters that accused both groups of being drug addicts and homosexuals. The response from both the Montoneros and the Youth was homophobic; they began using a chant at marches in which they denied being putos (literally "man-whores", used as a pejorative term for gay men) and faloperos (a pejorative slang term for people addicted to drugs).[lower-alpha 3][24]

In 1974, four months after reentering office, Perón reinstated the "Morality Brigade" tasked with state repression of sexuality. Repression of homosexuals exceeded historical levels, and the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance became active. By the end of 1974, the FLH had entirely separated itself from Peronism.[24]

In the media

In August 1972, the first interview with the Frente de Liberación Homosexual was published by the magazine Panorama in an article titled Homosexualidad, las voces clandestinas ("Homosexuality, clandestine voices"). The interview was with two FLH members who wore ski masks[16] that covered their faces.[25] In the interview, the two denounced the political repression that was ongoing at the time, debunked multiple pseudoscientific beliefs about homosexuality, and expressed that the FLH was interested in working with other left-wing groups.[16] They additionally compared machismo to fascism, describing it as "the fascism of the home".[lower-alpha 4][26] The Panorama article sensationalized the FLH and emphasized the similarities between it and the guerrilla groups in Argentina at the time.[16]

In September 1972, the FLH issued a press release after members were attacked by police officers while graffitiing the phrase Lesbiana no estás sola ("Lesbian you are not alone"). The statement denounced the aggression of the police, and was republished by many news outlets including Crónica and La Opinión.[16]

Members of the FLH were interviewed for the July 1973 issue of the magazine Así, which was titled Temores y deseos del homosexual argentino ("Fears and desires of the Argentine homosexual").[5] In the interview, they identified the FLH as connected to the Peronist left. On the front page of the September 1973 issue, the FLH endorsed the Justicialist Party.[24]

The final public appearance of the FLH was in an article published in Crónica on February 11, 1976, and titled Extraña protesta: Homosexuales se quejan de persecución ("Strange protest: Homosexuals complain of persecution"). The group effectively disbanded shortly afterward due to political repression.[27]

Publications

"The same system that oppresses and exploits you is the one that discriminates against us"

– Slogan used on FLH flyers from 1972[lower-alpha 5][16]

In 1972, in an effort to take advantage of public dissatisfaction with the government, the Frente de Liberación Homosexual began a propaganda campaign in which flyers on colored paper were thrown into public spaces. Each flyer was cut into an eye-catching shape and bore the image of a raised fist along with a slogan. The goal of the campaign was to foster empathy for gay people by equating the repression of homosexuals with political repression as a whole.[16]

Banners, flyers, and other communications by the group characteristically used non-uniform capitalization styles, as seen on the banner carried by FLH members at the inauguration of Héctor José Cámpora in May 1973.[28]

Homosexuales

In September 1973, the Frente de Liberación Homosexual published 5,000 copies of a one-off newspaper titled Homosexuales. Intended for public consumption, the newspaper was circulated among government officials and activists, and additionally sold at some newsstands; copies were sent to some international organizations as well. The articles were intended to appeal to political factions with which the FLH was interested in collaborating, and to respond to the most popular homophobic rhetoric of the time.[29]

The newspaper opened with a description of the FLH. Two articles were written by the Profesionales, with one discussing the history of homosexuality in Mesopotamia and arguing that it was not repressed, and the other drawing a connection between machismo and capitalism. A section discussed the Kinsey Report and argued that homosexuality was both inevitable and natural throughout human history. Also included were a reproduction of the leaflets distributed in Ezeiza at the return of Juan Perón, a petition to the Ministry of the Interior to repeal anti-homosexuality rules, and three articles by North American groups. One, written by a group of Catholic homosexuals, both defended the Catholic Church against common criticisms and attempted to appeal to progressive sections of the Church. The other two were both by Black groups in the United States, and included a letter from the Black Panthers as well as a leaflet from a group of Black homosexuals which rebuked revolutionaries who did not defend or support homosexuality.[29]

Somos

The Frente de Liberación Homosexual published an underground magazine titled Somos ("We Are")[9] from December 1973 through January 1976,[24] reaching a print circulation of 500 copies.[9] Mimeographed covertly in an office of the Workers' Socialist Party,[11] Somos took the form of 50-page issues published quarterly, though the two final issues in December 1975 and January 1976 were shorter.[30] In contrast to Homosexuales, which was intended to be read by non-homosexuals, the target audience of Somos was homosexuals themselves. Additionally, where previous publications by the FLH had included only text, Somos had illustrations.[30]

The first issue of Somos included the following message:[lower-alpha 6][9]

Once some of us dreamed of a place. It was an open, spacious place. There was an avenue called FREEDOM. Instead of exploiting each other, the people loved each other. Nobody attacked anyone, because everyone made love with whoever they wanted. [...] Nobody kept what the others had produced.

In addition to utopian messaging about sexual freedom, Somos included criticism of capitalism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, and the treatment of gay people in Cuba.[9] It also published messages from outside groups that were aligned with the FLH, including the Unión Feminista Argentina.[9] Articles included news from foreign homosexual groups, and recounted historical events including a major Buenos Aires police raid in 1954 and four legal actions against people accused of sodomy during the Middle Ages.[30] The FLH and Somos did not suggest that homosexuality in ancient Greece was accepted or encouraged, in contrast to many other homosexual movements which constructed founding myths involving the concept.[31]

The third issue of Somos, published in 1974, argued for pride in shared homosexual identity:[lower-alpha 7][30]

Like any oppressed group, homosexuals typically lack a satisfactory identity. [...] We must therefore construct a homosexual identity, first claiming our condition as human beings with the same rights as anyone else, free from the notions of disease or inferiority or abnormality. And secondly, we must proudly vindicate ourselves as homosexuals, throwing away once and for all the tremendous weight of shame and guilt that we have been made to feel.

It additionally included a section on methods of treatment for sexually transmitted infections.[32] Subsequent issues became less journalistic and more cultural, with articles telling stories of arrests and prison experiences in the first person, and included poetry and art. Many articles began using slang from within the community. Issue 4 included a list of hundreds of ways to refer to fellatio and anal sex, including hacer el frufrú ("to do the rustling") and tirar del fideo ("to pull the noodle").[30]

The sixth and final issue of Somos was published in January 1976, with its shorter number of pages reflecting the deterioration of the FLH under political repression. The group would dissolve shortly after.[27]

Dissolution

After the 1974 death of Juan Perón and during the presidency of Isabel Perón, Frente de Liberación Homosexual membership dropped from about a hundred to roughly a dozen people due to an increase in attacks on gay people by right-wing paramilitary groups.[33] José López Rega called for homosexuals to be exterminated, and stated that their increased visibility had been due to "international Marxism", causing the FLH to increase its secrecy. A few months later, in March 1976, police officers were ordered to "scare the homosexuals off the streets"[lower-alpha 8] as preparation began for the 1978 FIFA World Cup to be held in Argentina.[23] The FLH eventually dissolved in June 1976 as a result of severe political repression following the 1976 Argentine coup d'état.[33] Many members were tortured, disappeared, or murdered during the Dirty War, while others fled to Europe and to other countries in Latin America.[34]

Notes

- Original quote in Spanish: "los homosexuales son oprimidos social, cultural, moral y legalmente. Son ridiculizados y marginados, sufriendo duramente el absurdo impuesto brutalmente de la sociedad heterosexual monogámica"

- Original quote: "esta opresión proviene de un sistema social que considera a la reproducción como objetivo único del sexo"

- The full chant in the original Spanish was "No somos putos, no somos faloperos: somos soldados de Perón y Montoneros."

- Original quote: "El Machismo es el fascismo de entrecasa"

- Original quote: "El mismo sistema que te oprime y explota es el que nos discrimina a nosotros"

- Original quote: "Una vez, alguno de nosotros soñó con un lugar. Era un lugar abierto, espaciado. Había una avenida que se llamaba LIBERTAD. En lugar de explotarse los unos a los otros, la gente se amaba. Nadie agredía a nadie, porque todos hacían el amor con quien querían. (…) Nadie se quedaba con lo que habían producido los demás."

- Original quote: "Los homosexuales típicamente carecemos, como cualquier grupo oprimido, de una identidad satisfactoria. (...) Debemos pues construir una identidad homosexual, reivindicando en primer término nuestra condición de seres humanos con los mismos derechos de cualquier otro, exenta de noción de enfermedad o inferioridad o anormalidad. Y en segundo lugar, debemos reivindicaron orgullosamente como homosexuales, tirando de una vez por la borda el tremendo peso de la vergüenza y la culpa que nos han hecho sentir."

- Original quote: "espantar a los homosexuales de las calles"

References

Citations

- Encarnación 2011, p. 106.

- Bazán 2010, p. 340.

- Encarnación 2016, p. 57.

- Bazán 2010, p. 353.

- Bazán 2010, p. 341.

- Shaffer 2012, p. 66.

- Insausti 2019, p. 6.

- Bazán 2010, p. 342.

- González 2015.

- Ben & Insausti 2017, p. 299.

- Moscoso Cadavid 2011, p. 6.

- Domínguez Ruvalcaba 2016, p. 96.

- Domínguez Ruvalcaba 2016, p. 97.

- Bazán 2010, p. 340–341.

- Brown 2002, p. 120.

- Insausti 2019, p. 7.

- Bazán 2010, p. 344.

- Bazán 2010, p. 354.

- Insausti 2019, p. 8.

- Simonetto 2014, p. 2.

- Bazán 2010, p. 354–355.

- Insausti 2019, pp. 8–9.

- Modarelli 2009.

- Insausti 2019, p. 10.

- Bazán 2010, p. 343.

- Moscoso Cadavid 2011, p. 5.

- Insausti 2019, p. 13.

- Bazán 2010, p. 355.

- Insausti 2019, p. 9.

- Insausti 2019, p. 11.

- Moscoso Cadavid 2011, p. 14.

- Moscoso Cadavid 2011, p. 10.

- Brown 2002, p. 121.

- Encarnación 2018, p. 199.

Works cited

- Bazán, Osvaldo (2010). Historia de la homosexualidad en la Argentina: de la conquista de América al siglo XXI [History of homosexuality in Argentina: from the conquering of America to the 21st century] (Second ed.). Buenos Aires: Marea Editorial. pp. 340–355. ISBN 978-987-1307-35-7. OCLC 173722078.

- Ben, Pablo; Insausti, Santiago Joaquin (27 April 2017). "Dictatorial Rule and Sexual Politics in Argentina: The Case of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual, 1967–1976". Hispanic American Historical Review. 97 (2): 297–325. doi:10.1215/00182168-3824077. ISSN 0018-2168. S2CID 85560297.

- Brown, Stephen (2002). ""Con discriminación y represión no hay democracia": The Lesbian Gay Movement in Argentina". Latin American Perspectives. 29 (2): 119–138. doi:10.1177/0094582X0202900207. ISSN 0094-582X. JSTOR 3185130. S2CID 9046161.

- Domínguez Ruvalcaba, Héctor (2016). Translating the Queer: Body Politics and Transnational Conversations. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-78360-293-3. OCLC 944087265.

- Encarnación, Omar G. (2011). "Latin America's Gay Rights Revolution". Journal of Democracy. 22 (2): 104–118. doi:10.1353/jod.2011.0029. ISSN 1086-3214. S2CID 145221692 – via Project MUSE.

- Encarnación, Omar (2016). Out in the Periphery: Latin America's Gay Rights Revolution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190469726.

- Encarnación, Omar G. (2018). "A Latin American Puzzle: Gay Rights Landscapes in Argentina and Brazil". Human Rights Quarterly. 40 (1): 194–218. doi:10.1353/hrq.2018.0007. ISSN 1085-794X. S2CID 149302648 – via Project MUSE.

- González, Miguel (2015). "Sexo y Revolución. El Frente de Liberación Homosexual y la moral burguesa" [Sex and Revolution. The Homosexual Liberation Front and bourgeois morality.]. Jornada Interescuelas de Historia (in Spanish) – via Academia.edu.

- Insausti, Santiago Joaquin (2019). "Una historia del Frente de Liberación Homosexual y la izquierda en Argentina" [A history of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual and the left in Argentina]. Revista Estudos Feministas (in Spanish). 27 (2). doi:10.1590/1806-9584-2019v27n254280. ISSN 1806-9584. S2CID 199172795 – via SciELO.

- Modarelli, Alejandro (20 March 2009). "Víctimas sin nombre" [Nameless victims]. Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- Moscoso Cadavid, Javier Martín (2011). "Somos: representaciones de "nosotros" y "ellos" en la revista del F.L.H" [Somos: representations of "us" and "them" in the magazine of the F.L.H.]. Jornadas de Jóvenes Investigadores (in Spanish). Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, University of Buenos Aires – via Acta Académica.

- Shaffer, Andrew (14 December 2012). The Lavender Tide: LGBTQ Activism in Neoliberal Argentina (Thesis). University of San Francisco.

- Simonetto, Patricio (30 June 2014). "Imagen, estética y producción de sentido del Frente de Liberación Homosexual (1967–1976)" [Image, aesthetics and production of meaning of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual (1967-1976)]. Corpus (in Spanish). 4 (1). doi:10.4000/corpusarchivos.709. ISSN 1853-8037. S2CID 160892560.

Further reading

- Simonetto, Patricio (2014). "Imagen, estética y producción de sentido del Frente de Liberación Homosexual (1967–1976)" [Image, aesthetics and production of meaning of the Frente de Liberación Homosexual (1967-1976)]. Corpus (in Spanish). 4 (1). doi:10.4000/corpusarchivos.709. ISSN 1853-8037. S2CID 160892560.

- Simonetto, Patricio (12 June 2020). "La otra internacional. Prácticas globales y anclajes nacionales de la liberación homosexual en Argentina y México (1967–1984)" [The Other Internationale. Global Practices and National Anchors of Homosexual Liberation in Argentina and Mexico (1967-1984)]. Secuencia (in Spanish) (107). doi:10.18234/secuencia.v0i107.1697. ISSN 2395-8464. S2CID 226491548.

- Simonetto, Patricio (2017). Entre la injuria y la revolución: El Frente de Liberación Homosexual. Argentina, 1967–1976 [Between Injury and Revolution: The Frente de Liberación Homosexual. Argentina, 1967-1976] (PDF) (in Spanish). Bernal: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes. ISBN 978-987-558-419-8.

- Cid, Jorge (2020). "Formulación poética de la persecución y el activismo: Néstor Perlongher en el Frente de Liberación Homosexual argentino" [Poetic formulation of persecution and activism: Nestor Perlongher in the Argentine Frente de Liberación Homosexual]. Nomadías (in European Spanish) (29): 155–180. doi:10.5354/0719-0905.2021.61060 (inactive 1 August 2023). ISSN 0719-0905.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link)

External links

Media related to Frente de Liberación Homosexual at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Frente de Liberación Homosexual at Wikimedia Commons