Freydal

Freydal is an uncompleted illustrated prose narrative commissioned by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I in the early 16th century. It was intended to be a romantic allegorical account of Maximilian's own participation in a series of jousting tournaments in the guise of the tale's eponymous hero, Freydal. In the story, Freydal takes part in the tournaments to prove that he is worthy to marry a princess, who is a fictionalised representation of Maximilian's late wife, Mary of Burgundy.

The text was never completed, although a manuscript draft is held by the Austrian National Library. Over 200 high quality drawings were created to be used as planning sketches, 203 of which are held in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., with a small number of others preserved in the British Museum and the Vatican Library. Based on these drawings, 256 miniature paintings were created by court painters, and 255 are preserved in an illuminated manuscript, the Freydal tournament book held by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. These miniatures vividly record the different types of jousts that were popular at the time as well as the court masquerades, or ‘mummeries’, that took place at the end of the day after each tournament. It is the most extensive visual record of late medieval tournaments and court masquerades that exists.

The written story and illustrations were never brought together in a single work, as Maximilian had originally intended. Freydal survives as three separate elements: a draft incomplete text, the planning drawings and the tournament book.

Background

Maximilian I and his father Frederick III were part of what was to become a long line of Holy Roman Emperors from the House of Habsburg. Maximilian was elected King of the Romans in 1486; upon his father's death in 1493 he succeeded to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire.[2]

During his reign, Maximilian commissioned a number of humanist scholars and artists to assist him in completing a series of projects, in different art forms, intended to immortalize his life and deeds and those of his Habsburg ancestors.[3] He referred to these projects as Gedechtnus ("memorial"),[4] and included a series of stylised autobiographical works: Freydal, the prose romance Weisskunig, and the poem Theuerdank.[3]

Freydal and Theuerdank are closely linked and together give an allegorical account of the events leading to Maximilian's marriage to Mary of Burgundy in 1477.[5] Mary died five years later, in 1482.[6] In Freydal, which is partly a tribute to Mary,[7] the eponymous hero pursues his fair lady by jousting in tournaments.[8] Theuerdank is effectively a sequel in which the hero overcomes dangers on the journey to his wedding.[5] Freydal has a comedic tone which contrasts with Theuerdank, which has more of the character of a tragedy.[9]

The theme of Freydal reflects Maximilian's lifelong enthusiasm for jousting. He attended his first tournament at the age of 14 and was captivated by its traditions and spectacle.[8] He staged many tournaments, with major ones held to celebrate his wedding to Mary of Burgundy in 1477, his coronation as King of the Romans in 1486 and on the occasion of the First Congress of Vienna in 1515.[8] Unusually for a powerful ruler, Maximilian was himself a frequent participant in tournaments.[10] The first tournament he is recorded as participating in was in 1485 when he was 26[11] and he continued until 1511, when he was in his 50s.[10] His affinity for jousting contributed to his soubriquet the “last knight”.[8]

Creation and history

Maximilian took a leading part in the creation of Freydal,[13] a name derived from Freyd-alb, meaning "white joyful young man".[14] He appears to have begun planning the work in 1502 when he instructed his court taylor, Martin Trummer, "to have drawn in a book all those costumes as yet seen in mummeries organised by his majesty".[15] A “mummery” was a late medieval courtly masquerade or costumed dance.[16]

The next development was the commissioning of planning sketches for the entire work, created over the following ten years. They were drawn in pen on laid paper, using brown and black ink with watercolour over black chalk and leadpoint.[15] A collection of 203 of these are housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.[17] A small number of additional drawings are held at the British Museum and the Vatican Library. Maximilian's instructions on the subjects to be illustrated as well as corrections, in his own hand, of some of the proofs have survived.[15]

In 1511, Maximilian dictated some of the text to his secretary, Max Trytssaurwein,[13] (or Marx Treitzsauerwein[18]) and the following year wrote "Freydal is half conceived, the largest part of which we have made in Cologne".[15] The work was never completed,[19] however, and the text exists only in draft form.[20] The manuscript text dictated to Treitzsauerwein, and corrected in Maximilian's hand, is held by the Austrian National Library in Vienna.[21]

(Volume_II)%252C_c._1515%252C_NGA_216067.jpg.webp)

Although the text was never finalised, 256 high quality miniatures,[20] based on the planning sketches, were created between 1512 and 1515 to illustrate the text.[5] These were painted on paper in gouache with gold and silver highlights over pen, pencil and leadpoint[5] by two dozen anonymous[9] court artists under the direction of the imperial master-taylor.[19] All but one of the paintings are preserved in an illuminated manuscript ‘tournament book’ held by the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.[5] The remaining painting has been missing since at least 1600.[5]

It was intended to print and publish the work with woodcut illustrations derived from the miniatures.[19] Although Maximilian never succeeded in doing this,[19] and the text remained only a draft, five of the illustrations were trial printed.[20] These were from woodcuts made in about 1516 by Albrecht Dürer, albeit the cutting was somewhat rough. A sixth woodcut has been attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder.[22] One of the woodcut blocks has survived, and is held by the Kupferstichkabinett Berlin.[23]

In modern times, the Kunsthistorisches Museum illuminated manuscript tournament book has been published twice. A multi-volume edition, edited by Quirin von Leitner (de), was published in Vienna in stages between 1880 and 1882.[13][24] In 2019, the German publisher, Taschen, published the entire tournament book in a single volume, edited by Stefan Krause.[9][25]

Content

Narrative

Based on the draft text preserved in the Austrian National Library,[27][28] the story is an account of a series of tournaments in which Freydal – a young knight and Maximilian's literary alter ego – demonstrates his valour in combat in order to earn honour and fame[29] and to win the hand of a princess.[20] Freydal is the son of a “mighty prince” and he is born with “noble virtue”; his heraldic colours are white, red, and black, symbolising purity, fire, and bravery.[29]

The narrative begins with three noble ladies asking Freydal to compete in the tournaments.[20] A description of sixty-four tournaments follows in a ritualised and repetitive pattern.[29] Each is hosted by one of the finest courts in the land and comprises three events: two different types of jousting; a foot combat; and a masquerade ball.[20] Freydal competes in each tournament and almost always wins.[13] Once all the tournaments are completed, Freydal receives a letter from one of the noble ladies who, it transpires, is a powerful queen; in the letter, she professes her love for him. The narrative ends with Freydal setting out to search for her, and Theuerdank then takes up the subsequent story.[20]

The work reflects Maximilian's vanity, as exemplified by a poem which forms part of the draft text:[7]

This did the gallant Freydal

In knightly deeds of fame

Thus rendering illustrious

The glories of his name.

His virtues and his goodness

Are manifest to all;

His many glorious triumphs

At tilt, at masks and ball...

His like will ne’er be seen again.[30]

However, the tournaments described are based on encounters Maximilian actually had. This is evidenced by a list of people involved in the story in the first seven quires of the draft text, and who are known to have been actual courtiers.[29]

Illuminated manuscript tournament book

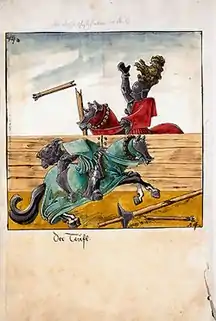

The miniatures in the tournament book manuscript illustrate the types of jousting popular at the time, both on horse and on foot.[9] Freydal features in each illustrated combat and his opponent is an historical figure with whom Maximilian actually jousted.[9] Each picture, in the lower margin, identifies the name of the opponent and the other courtiers depicted.[12]

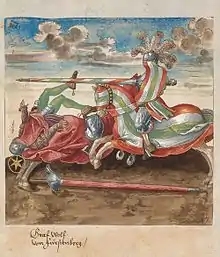

Two types of joust – Rennen and Stechen – are depicted for each tournament.[13][20] Rennen, or “jousts of war”, are where the lance has a sharpened tip and Stechen, or “jousts of peace”, are where the lance has a blunted tip.[32][21] Within these two broad groupings, eleven sub-types are shown.[20] In the Welsches Gestecht (Italian joust of peace) a board separates the jousters so that they can ride more closely to each other and strike their opponent frontally with greater force. This results in a spectacular splintering of the lances. In the Scharfrennen (joust of war with flying shields) the shield is shown loosely fixed to the rider's breastplate, the aim being to dislodge it. In contrast, the objective of the Antzogenrennen is to unseat the opponent and his shield is fixed to his armour.[20] The Feldrennen (or Kampfrennen) jousts replicate skirmishes in war and the riders wear battlefield armour. The rarest type of joust depicted is the Krönlrennen where one rider wears the armour of a joust of peace but wields the lance of a joust of war and the other rider has the opposite combination.[16]

One of the most spectacular jousts depicted is the Bundrennen (joust of war with flying shields without bevors)[20] and its variation, Geschifttartschen-Rennen (joust of war with flying and exploding shields).[33] In the Bundrennen, the shield is held in place on the rider's breastplate with a complicated spring mechanism and when it is struck in the right place by the opponent it is ejected high into the air.[20] The Geschifttartschen-Rennen increases the spectacle by attaching multiple triangular platelets to the shield which, when the shield is ejected, come loose and explode into the air like a firework display.[33] Maximilian claimed to have invented this type of joust.[8]

In each of the tournaments, the participants are shown engaging in a foot combat. A variety of weapons are used, including iron clubs (Eisenkolben), flails (Drischel), swords (Turnierschwert)[34] and daggers.[35] The mêlée is also shown in the manuscript.[13]

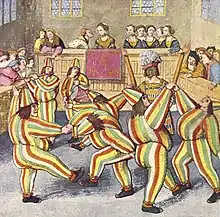

After each of the sixty-four tournaments is a scene depicting a moresca (a pantomime dance) or other post-tournament festivities with male courtiers, including the knights who had competed in the tournament, dressing up to dance in a variety of exotic costumes.[19] Known as ‘mummeries’, these were a regular feature of the evening entertainment after tournaments.[16] Although the illustrations usually depict dances — either row or circle dancing — sometimes other types of mummeries are shown, such as burlesques of little known court ceremonies, prize-givings and mock battles, for example a pike battle between peasants and Landsknechte.[36]

The male courtiers in the mummeries in the manuscript dress up, amongst other things, in costumes based on nationality or ethnicity, for example Turkish, Venetian or Burgundian costume, or as animals such as apes and creatures with bird's heads.[19] In one masquerade illustrated, the male participants engage in cross-dressing and wear women's gowns.[16]

In each scene, all the men are dressed in the same costume and normally wear a mask. Women, however, are always shown wearing their usual court attire.[19] In each of these post-tournament pictures, Freydal appears carrying a torch and wearing a mask.[19]

Scenes from the Kunsthistorisches Museum Freydal illuminated manuscript

Significance

Tournament books were a feature of late medieval and renaissance courtly culture and provide a graphic record of jousting and its associated rituals. Notable examples include King René's Tournament Book and the tournament books of the Electors of Saxony.[37] The Freydal illuminated manuscript is considered one of the most important[37] and precious[13] of this genre. As the largest surviving tournament book, it provides an unparalleled pictorial source of jousting from the late medieval period.[38]} It is also the only one to depict spectacular falls.[8] In addition to illustrating the jousts themselves, it represents a remarkable catalogue of the weaponry used during tournaments [8] and is the most extensive record of mummery, the early court masquerade, that exists.[16] The manuscript has been recognised in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme.[39]

However, Freydal was intended to be not only an artistic work but also political propaganda.[40] As part of what he called his ‘memorial projects’ or Gedechtnus, Maximilian I used literary and visual works such as Freydal to model and enhance his public image.[41] Traditionally, Maximilian is seen as doing this in a backward-looking and, even, in a delusional way, by harking back to a former age.[42] As part of this view, his aim was perceived as making up for the limitations to his actual power by the use of media like printing to maximize his imperial aura.[41] As the historian Jan-Dirk Müller (de) has said, the extent to which Maximilian employed this strategy meant that his court “literally existed on paper: to a large extent it was a virtual quantity”.[41] However, the notion that Maximilian was an unsuccessful ruler who indulged in his Gedechtnus projects either because he was fantatasist or to compensate for his weakness has been challenged.[42] According to Klaus Albrecht Schröder, Maximilian was "the world's most powerful monarch at the time".[43] Increasingly, his skilful use of new media, such as the printing press, for propaganda purposes is seen as part of his success in laying the foundations of future Habsburg power.[42]

References

- Krause 2014, pp. 177–178.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 303.

- Watanabe-O'Kelly 2000, p. 94.

- Kleinschmidt 2008, p. 162.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 120.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 300.

- Clephan 1995, p. 88.

- Freeman 2019.

- McLaren 2019.

- Anderson 2020, pp. 192–193.

- Anderson 2017, pp. 104–105.

- Locke 2015, p. 123.

- Clephan 1995, p. 87.

- Strobl 1913, p. 4.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 123.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 122.

- Terjanian 2019, pp. 120, 123.

- Kleinschmidt 2008, p. 178.

- Locke 2015, p. 121.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 121.

- Silver 2002, p. 63.

- Kurth 1963, p. 36.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 129.

- Leitner 1880–1882.

- Krause 2019.

- Krause 2014, pp. 172, 174.

- Terjanian 2019, pp. 121, 122 note 2.

- Silver 2002, pp. 63–64.

- Silver 2002, p. 64.

- Clephan 1995, p. 88, note 1.

- Krause 2014, pp. 175–176.

- Jackson 2001, p. 759.

- Terjanian 2019, p. 125.

- Krause 2014, p. 179.

- Krause 2014, p. 181.

- Silver 2013, p. 184.

- Krause 2014–2015.

- Terjanian 2019, pp. 120–121.

- Taschen Catalogue.

- Barber 1974, p. 298.

- Müller 2003, pp. 307–308.

- Whaley 2012, pp. 1237–1238.

- Schröder 2012, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Natalie (2017). The Tournament and its Role in the Court Culture of Emperor Maximilian I (1459-1519) (phd). University of Leeds White Rose eTheses.

- Anderson, Natalie (2020). "Power and Pageantry: The Tournament at the Court of Maximilian I". In Murray, Alan V.; Watts, Karen (eds.). The Medieval Tournament as Spectacle: Tourneys, Jousts and Pas d'Armes 1100-1600. The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-542-7.

- Barber, Richard W. (1974). The Knight and Chivalry. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-041-3.

- Clephan, Robert Coltman (1995) [1919]. The Mediaeval Tournament. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-28620-4.

- Freeman, Laura (4 May 2019). "The joy of jousting". The Spectator. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Jackson, William (2001). "Tournaments". In Jeep, John M. (ed.). Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-66540-7.

- Kleinschmidt, Harald (2008). Ruling the Waves: Emperor Maximilian I, the Search for Islands and the Transformation of the European World Picture C. 1500. Brill. ISBN 978-90-6194-020-3.

- Krause, Stefan (2014–2015). "Freydal, the Tournament Book of Emperor Maximilian I: The Washington Manuscript". National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

- Krause, Stefan (2014). "Die ritterspiel als ritter Freydalb hat gethon aus ritterlichem gmute – Das Turnierbuch Freydal Kaiser Maximilians I.". In Haag, Sabine; et al. (eds.). Kaiser Maximilian I: der letzte Ritter und das höfische Turnier. Schnell & Steiner. ISBN 978-3-7954-2842-6.

- Krause, Stefan, ed. (2019). Das Turnierbuch Kaiser Maximilians I. Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-7681-9.

- Kurth, Willi (1963). The Complete Woodcuts of Albrecht Dürer. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-21097-1.

- Leitner, Quirin von, ed. (1880–1882). Freydal. Des Kaisers Maximilian I. Turniere und Mummereien. Holzhausen.

- Locke, Ralph P. (2015). Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01237-0.

- McLaren, Iona (25 May 2019). "Freydal: the 16th-century comic that captures the thrill of jousting". The Telegraph. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Müller, Jan-Dirk (2003). "The Court of Emperor Maximilian I". In Gosman, Martin; et al. (eds.). Princes and Princely Culture: 1450-1650 Vol. 1. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-13572-7.

- Schröder, Klaus Albrecht (2012). "Foreword and acknowledgements". In Michel, Eva; Sternat, Maria Luise (eds.). Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Dürer (PDF). Prestel; Albertina. ISBN 978-3-7913-5172-8.

- Silver, Larry (2002). "Shining Armor: Emperor Maximilian, Chivalry and War". In Cuneo, Pia F. (ed.). Artful Armies, Beautiful Battles: Art and Warfare in the Early Modern Europe. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11588-0.

- Silver, Larry (2013). "Caesar Ludens: Emperor Maximilian I and the WAninf Middle Ages". In Sax, Benjamin C.; Gold, Penny Schine (eds.). Cultural Visions: Essays in the History of Culture. ISBN 978-90-420-0490-0.

- Strobl, Joseph (1913). Studien über die literarische Tätigkeit Kaiser Maximilian I. Georg Reimer. ISBN 978-3-11-148391-7.

- Taschen Catalogue. "The Legendary Tales of Emperor Maximilian I". Taschen.

- Terjanian, Pierre, ed. (2019). The Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-674-7.

- Watanabe-O'Kelly, Helen (2000). The Cambridge History of German Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78573-0.

- Whaley, Joachim (2012). "Heinz Noflatscher, Michael A. Chisholm, and Bertrand Schnerb, eds. Maximilian I. (1459–1519): Wahrnehmung — Übersetzungen — Gender.". Review. Renaissance Quarterly. 65 (4). doi:10.1086/669392. S2CID 163874672.

External links

- Freydal. Des Kaisers Maximilian I. Turniere und Mummereien 1880-1882 edition (Q.von Leitner, ed.) from Internet Archive

- Kunsthistorisches Museum: Freydal – Das Turnierbuch Kaiser Maximilians I. (in German)

- National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.: Freydal drawings

- Freydal. Medieval Games. The Book of Tournaments of Emperor Maximilian I, Taschen Catalogue (in English)