Jousting

Jousting is a medieval and renaissance martial game or hastilude between two combatants either on horse or on foot.[1] The joust became an iconic characteristic of the knight in Romantic medievalism.

Renaissance-era depiction of a joust in traditional or "high" armour, based on then-historical late medieval armour (Paulus Hector Mair, De arte athletica, 1540s) | |

| First played | 14th century, Europe |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Yes |

| Type | Hastilude |

| Venue | Castles, tiltyards |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Europe |

The term is derived from Old French joster, ultimately from Latin iuxtare "to approach, to meet". The word was loaned into Middle English around 1300, when jousting was a very popular sport among the Anglo-Norman knighthood. The synonym tilt (as in tilting at windmills) dates c. 1510.

Jousting on horse is based on the military use of the lance by heavy cavalry. It transformed into a specialized sport during the Late Middle Ages, and remained popular with the nobility in England and Wales, Germany and other parts of Europe throughout the whole of the 16th century (while in France, it was discontinued after the death of King Henry II in an accident in 1559).[2] In England, jousting was the highlight of the Accession Day tilts of Elizabeth I and of James VI and I, and also was part of the festivities at the marriage of Charles I.[3]

Jousting was discontinued in favour of other equestrian sports in the 17th century, although non-contact forms of "equestrian skill-at-arms" disciplines survived. There has been a limited revival of theatrical jousting re-enactment since the 1970s.

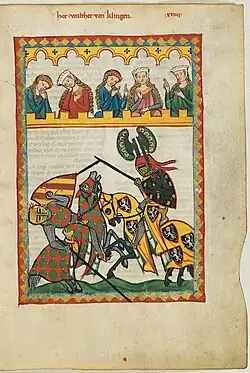

Medieval joust

The medieval joust has its origins in the military tactics of heavy cavalry during the High Middle Ages. By the 14th century, many members of the nobility, including kings, had taken up jousting to showcase their own courage, skill and talents, and the sport proved just as dangerous for a king as a knight, and from the 15th century on, jousting became a sport (hastilude) without direct relevance to warfare.

High Middle Ages

From the 11th to 14th centuries when medieval jousting was still practised in connection to the use of the lance in warfare, armour evolved from mail (with a solid, heavy helmet, called a "great helm", and shield) to plate armour. By 1400, knights wore full suits of plate armour, called a "harness" (Clephan 28–29).

In this early period, a joust was still a (martial) "meeting", i.e. a duel in general and not limited to the lance. Combatants would begin riding on one another with the lance, but might continue with shorter range weapons after the distance was closed or after one or both parties had been unhorsed. Tournaments in the High Medieval period were much rougher and less "gentlemanly" affairs than in the late medieval era of chivalry. The rival parties would fight in groups, with the aim of incapacitating their adversaries for the sake of gaining their horses, arms and ransoms.[4]

Late Middle Ages

With the development of the courtly ideals of chivalry in the late medieval period, the joust became more regulated. This tendency is also reflected in the pas d'armes in general. It was now considered dishonourable to exploit an opponent's disadvantage, and knights would pay close attention to avoid being in a position of advantage, seeking to gain honour by fighting against the odds. This romanticised "chivalric revival" was based on the chivalric romances of the high medieval period, which noblemen tried to "reenact" in real life, sometimes blurring the lines of reality and fiction.

The development of the term knight (chevalier) dates to this period. Before the 12th century, cniht was a term for a servant. In the 12th century, it became used of a military follower in particular. Also in the 12th century, a special class of noblemen serving in cavalry developed, known as milites nobiles. By the end of the 13th century, chivalry (chyualerye) was used not just in the technical sense of "cavalry" but for martial virtue in general. It was only after 1300 that knighthood (kniȝthod, originally a term for "boyhood, youth") came to be used as a junior rank of nobility. By the later 14th century, the term became romanticised for the ideal of the young nobleman seeking to prove himself in honourable exploits, the knight-errant, which among other things encompassed the pas d'armes, including the joust. By the 15th century, "knightly" virtues were sought by the noble classes even of ranks much senior than "knight".[5] The iconic association of the "knight" stock-character with the joust is thus historical, but develops only at the end of the Middle Ages.

Records of jousting by Froissart

The Chronicles of Froissart, written during the 1390s, and covering the period of 1327 to 1400, contain many details concerning jousting in this era. The combat was now expected to be non-lethal, and it was not necessary to incapacitate the opponent, who was expected to honourably yield to the dominant fighter. The combat was divided into rounds of three encounters with various weapons, of which the joust proper was one. During this time, the joust detached itself from the reality on the battlefield and became a chivalric sport. Knights would seek opportunities to duel opponents from the hostile camp for honour off the battlefield.

As an example, Froissart[6][7] records that, during a campaign in Beauce in the year 1380, a squire of the garrison of Toury castle named Gauvain Micaille (Michaille)—also mentioned in the Chronique du bon duc Loys de Bourbon as wounded in 1382 at Roosebeke, and again in 1386; in 1399 was in the service of the duke of Bourbon[8][9]—yelled out to the English,

Is there among you any gentleman who for the love of his lady is willing to try with me some feat of arms? If there should be any such, here I am, quite ready to sally forth completely armed and mounted, to tilt three courses with the lance, to give three blows with the battle axe, and three strokes with the dagger. Now look, you English, if there be none among you in love.

The challenge was answered by a squire named Joachim Cator, who said "I will deliver him from his vow: let him make haste and come out of the castle."

Micaille came to meet his opponent with attendants carrying three lances, three battle-axes, three swords and three daggers. The duel began with a joust, described as follows:

When they had taken their stations, they gave to each of them a spear, and the tilt began; but neither of them struck the other, from the mettlesomeness of their horses. They hit the second onset, but it was by darting their spears.[10]

The meeting was then adjourned, and continued on the next day.

They met each other roughly with spears, and the French squire tilted much to the satisfaction of the earl: but the Englishman kept his spear too low, and at last struck it into the thigh of the Frenchman. The earl of Buckingham as well as the other lords were much enraged by this, and said it was tilting dishonorably; but he excused himself, by declaring it as solely owing to the restiveness of his horse.[11]

In spite of the French squire's injury, the duel was continued with three thrusts with the sword. After this, the encounter was stopped because of the Micaille's loss of blood. He was given leave to rejoin his garrison with a reward of a hundred francs by the earl of Buckingham, who stated that he had acquitted himself much to his satisfaction.

Froissart describes a tournament at Cambray in 1385, held on the marriage of the Count d'Ostrevant to the daughter of Duke Philip of Burgundy. The tournament was held in the market-place of the town, and forty knights took part. The king jousted with a knight of Hainault, Sir John Destrenne, for the prize of a clasp of precious stones, taken off from the bosom of the Duchess of Burgundy; it was won by Sir Destrenne, and formally presented by the Admiral of France and Sir Guy de la Trimouille.

Arena, procedure and armor

The lists, or list field, was the arena where a jousting event was held. More precisely, it was the roped-off enclosure where tournament fighting took place.[12] In the late medieval period, castles and palaces were augmented by purpose-built tiltyards as a venue for "jousting tournaments". Training for such activities included the use of special equipment, of which the best-known was the quintain.

The medieval joust took place on an open field. Indeed, the term joust meant "a meeting" and referred to arranged combat in general, not just the jousting with lances. At some point in the 14th century, a cloth barrier was introduced as an option to separate the contestants. This barrier was presumably known as tilt in Middle English (a term with an original meaning of "a cloth covering"). It became a wooden barrier or fence in the 15th century, now known as "tilt barrier", and "tilt" came to be used as a term for the joust itself by c. 1510. The purpose of the tilt barrier was to prevent collisions and to keep the combatants at an optimal angle for breaking the lance. This greatly facilitated the control of the horse and allowed the rider to concentrate on aiming the lance. The introduction of the barrier seems to have originated in the south, as it only became a standard feature of jousting in Germany in the 16th century, and was there called the Italian or "welsch" mode.[13] Dedicated tilt-yards with such barriers were built in England from the time of Henry VIII.

A knightly duel in this period usually consisted in three courses of jousting, and three blows and strokes exchanged with battle-axes, swords, and daggers. This number tended to be extended towards the end of the century, until the most common number was five, as in the duel between Sir Thomas Harpenden and Messire Jean des Barres, at Montereau sur Yonne in 1387 (cinq lances a cheval, cinq coups d'épée, cinq coups de dague et cinq coups de hache). Later it could be as high as ten or even twelve. In the 1387 encounter, the first four courses of the joust were run without decisive outcome, but in the fifth Sir Thomas was unhorsed and lost consciousness. He was revived, however, and all the strokes and blows could be duly exchanged, without any further injury.

On another instance, a meeting with sharp lances was arranged to take place near Nantes, under the auspices of the Constable of France and the Earl of Buckingham. The first encounter was a combat on foot, with sharp spears, in which one of the cavaliers was slightly wounded; the pair then ran three courses with the lance without further mishap. Next Sir John Ambreticourt of Hainault and Sir Tristram de la Jaille of Poitou advanced from the ranks and jousted three courses, without hurt. A duel followed between Edward Beauchamp, son of Sir Robert Beauchamp, and the bastard Clarius de Savoye. Clarius was much the stronger man of the two, and Beauchamp was unhorsed. The bastard then offered to fight another English champion, and an esquire named Jannequin Finchly came forward in answer to the call; the combat with swords and lances was very violent, but neither of the parties was hurt.

Another encounter took place between John de Chatelmorant and Jannequin Clinton, in which the Englishman was unhorsed. Finally Chatelmorant fought with Sir William Farrington, the former receiving a dangerous wound in the thigh, for which the Englishman was greatly blamed, as being an infraction of the rules of the tourney, but an accident was pleaded just as in the case of the 1380 duel between Gauvain Micaille and Joachim Cator.[14]

Specialised jousting armour was produced in the late 15th to 16th century. It was heavier than suits of plate armour intended for combat, and could weigh as much as 50 kg (110 lb), compared to some 25 kg (55 lb) for field armour; as it did not need to permit free movement of the wearer, the only limiting factor was the maximum weight that could be carried by a warhorse of the period.[15]

Horses

The two most common kinds of horses used for jousting were warmblood chargers and larger destriers. Chargers were medium-weight horses bred and trained for agility and stamina. Destriers were heavier, similar to today's Andalusian horse, but not as large as the modern draft horse.

During a jousting tournament, the horses were cared for by their grooms in their respective tents. They wore caparisons, a type of ornamental cloth featuring the owner's heraldic signs. Competing horses had their heads protected by a chanfron, an iron shield for protection from otherwise lethal lance hits.

Other forms of equipment on the horse included long-necked spurs that enabled the rider to control the horse with extended legs, a saddle with a high back to provide leverage during the charge or when hit, as well as stirrups for the necessary leverage to deliver blows with the lance.

15th century

From 10 July to 9 August 1434, the Leonese knight Suero de Quiñones and ten of his companions encamped in a field beside a bridge and challenged each knight who wished to cross it to a joust. This road was used by pilgrims all over Europe on the way to a shrine at Santiago de Compostela, and at this time of the summer, many thousands would cross the bridge. Suero and his men swore to "break 300 lances" before moving on. The men fought for over a month, and after 166 battles Suero and his men were so injured they could not continue and declared the mission complete.[16]

During the 1490s, emperor Maximilian I invested much effort into perfecting the sport, for which he received his nickname of "The Last Knight". Rennen and Stechen were two sportive forms of the joust developed during the 15th century and practised throughout the 16th century. The armours used for these two respective styles of the joust were known as Rennzeug and Stechzeug, respectively. The Stechzeug in particular developed into extremely heavy armour which completely inhibited the movement of the rider, in its latest forms resembling an armour-shaped cabin integrated into the horse armour more than a functional suit of armour. Such forms of sportive equipment during the final phase of the joust in 16th-century Germany gave rise to modern misconceptions about the heaviness or clumsiness of "medieval armour", as notably popularised by Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.[17][18] The extremely heavy helmets of the Stechzeug are explained by the fact that the aim was to detach the crest of the opponent's helmet, resulting in frequent full impact of the lance to the helmet.

By contrast the Rennen was a type of joust with lighter contact. Here, the aim was to hit the opponent's shield. The specialised Rennzeug was developed on the request of Maximilian, who desired a return to a more agile form of joust compared to the heavily armoured "full contact" Stechen. In the Rennzeug, the shield was attached to the armour with a mechanism of springs and would detach itself upon contact.

Post-medieval period

In France, the death of King Henry II in 1559 from wounds suffered in a tournament led to the end of jousting as a sport.[19]

The tilt continued through Henry VIII and onto the reign of Elizabeth I. Under her rule, tournaments were seen as more of a parade or show than an actual martial exercise.[20]

The last Elizabethan Accession Day tilt was held in November 1602; Elizabeth died the following spring. Tilts continued as part of festivities marking the Accession Day of James I, 24 March, until 1624, the year before his death.[21][22] In the early 17th century, the joust was replaced as the equine highlight of court festivities by large "horse-ballet" displays called carousels, although non-combat competitions such as the ring-tilt lasted until the 18th century. Ring tournaments were introduced into North America, and jousting continues as the state sport of Maryland.[23]

One attempt to revive the joust was the Eglinton Tournament of 1839.

_MET_DT773.jpg.webp)

_MET_DP256960.jpg.webp) Parade Armour of Henry II of France, c. 1553-55

Parade Armour of Henry II of France, c. 1553-55_MET_DT205963.jpg.webp) Armour for King Henry VIII by Matthew Bisanz, 1544

Armour for King Henry VIII by Matthew Bisanz, 1544 Armour worn by King Henry VIII

Armour worn by King Henry VIII

Modern revivals

Modern-day jousting

Jousting reenactors have been active since the 1970s. A more popular modern-day jousting show took place in 1972 at the Principality of Gwrych in North Wales near Abergele. Various companies, such as Knights Limited, held organized shows with anywhere between five and fifty actors present.

Between 1980 and 1982, the Little England theme park in Orlando, Florida was planned to become a jousting stadium, ultimately being cancelled due to high-interest rates. Other companies such as The Medieval Times include this sport in its dinner show. Jousting shows are also held seasonally at Warwick Castle and Hever Castle in England. Groups like the Knights of Royal England travel around Britain and Europe staging medieval jousting tournaments. At the Danish museum Middelaldercentret, daily jousting tournaments are held during the season.[24][25]

Competitive jousting

The Knights of Valour was a theatrical jousting group formed by Shane Adams in 1993. Members of this group began to practice jousting competitively, and their first tournament was held in 1997. Adams founded the World Championship Jousting Association (WCJA) as a body dedicated to jousting as a combat sport, which held its inaugural tournament in Port Elgin, Ontario on 24 July 1999.[26][27] The sport is presented in the 2012 television show Full Metal Jousting, hosted by Adams. The rules are inspired by Realgestech (also Plankengestech), one of the forms of stechen practised in 16th-century Germany, where reinforcing pieces were added to the jousting armour to serve as designated target areas. Instead of using a shield, the jousters aim for such a reinforcing piece added to the armour's left shoulder known as Brechschild (also Stechtartsche). A number of Jousting events are held regularly in Europe, some organised by Arne Koets, including The Grand Tournament of Sankt Wendel and The Grand Tournament at Schaffhausen.[28] Koets is one of a number of Jousters who travel internationally to events.

In popular culture

Medieval jousting and the culture surrounding it are main plot points in the 2001 film A Knight's Tale.[29]

References

- Hart, Clive (2022). The Rise and Fall of the Mounted Knight. note 55 of Ch. 6: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-3990-8205-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Barber, Richard; Barker, Juliet (1989). Tournaments: Jousts, Chivalry and Pageants in the Middle Ages. Boydell. pp. 134, 139. ISBN 978-0-85115-470-1.

- Young 1987, pp. 201–208.

- L.F. Salzman, "English Life in the Middle Ages," Oxford, 1950. "These early tournaments were very rough affairs and in every sense, quite unlike the chivalrous contests of later days; the rival parties fought in groups, and it was considered not only fair but commendable to hold off until you saw some of your adversaries getting tired and then to join in the attack on them; the object was not to break a lance in the most approved style, but frankly to disable as many opponents as possible for the sake of obtaining their spears, arms, and ransoms."

- OED, s.v. "knight", "knighthood", "chivalry".

- Froissart, John, Chronicles of England, France, Spain and the adjoining countries from the latter part of the reign of Edward II to the coronation of Henry IV in 12 volumes, vol. 1 (1803–10 ed.), Global folio, pp. 613–615

- Gauvain, CA: Nipissingu, archived from the original on 14 July 2009, retrieved 26 February 2007

- Luce, Siméon (1869), Chroniques, Paris J. Renouard, p. cvii

- Coltman 1919, p. 29.

- Johnes, Thomas. Sir John Froissart's Chronicles of England, 208

- "Froissart: A Challenge is Fought Before the Earl of Buckingham". uts.nipissingu.ca.

- Hopkins, Andrea (2004). Tournaments and Jousts: Training for War in Medieval Times. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8239-3994-7.

- Frieder, Braden K. (2008). Chivalry & The Perfect Prince: Tournaments, Art, and Armor at the Spanish Habsburg Court. Truman State University Press. p. 7f. ISBN 978-1-931112-69-7.

- Coltman 1919, p. 30 summarizing "5", Froissart's Chronicles, p. 47

- Edge, David; Paddock, John Miles (1988). Arms & armor of the medieval knight. Crescent Books. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-517-64468-3.

- Pedro Rodríguez de Lena (1930), A Critical Annotated Edition of El Passo Honroso de Suero de Quiñones, 1977 edition ISBN 978-84-7392-010-0

- Ellis, John (1978). Cavalry: The History of Mounted Warfare. Putnam.

- Woosnam-Savage, Robert C; Anthony Hall (2002). Brassey's Book of Body Armor. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1-57488-465-4.

- Martin, Graham (May 2001). "The death of Henry II of France: A sporting death and post-mortem". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 71 (5): 318–20. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1622.2001.02102.x. PMID 11374484. S2CID 22308185.

- Schulze, Ivan L. (1933). "Notes on Elizabethan Chivalry and "The Faerie Queene"". Studies in Philology. 30 (2): 148–159. JSTOR 4172200.

- Strong 1977, pp. 137–38.

- Young 1987, p. 208.

- Orians, G. Harrison (1941). "The Origin of the Ring Tournament in the United States" (PDF). Maryland Historical Magazine. 36: 263–277.

- "Historic Royal Palaces > Home > Hidden > Press releases 2006–2008 > Tournament at the Tower". Hrp.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Ridderturneringer". Middelaldercentret.dk. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ICE: Webmaster. "Mounted Training at AEMMA". Aemma.org. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- Slater, Dashka (8 July 2010). "Is Jousting the Next Extreme Sport?". New York Times.

- "An Interview with Arne Koets, jouster" The Jousting Life, December 2014

- Ebert, Roger (11 May 2001). "A Knight's Tale movie review and film summary (2001)". rogerebert.com. Ebert Co. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

Sources

- Coltman, C. R. (1919), The tournament; its periods and phases.

- Nadot, Sébastien (2010), Rompez les lances ! Chevaliers et tournois au Moyen Age [Break lances! Knights and tournaments in the Middle Ages] (in French), Paris: Autrement.

- Strong, Roy (1977), The Cult of Elizabeth: Elizabethan Portraiture and Pageantry, Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-23263-7.

- Young, Alan (1987), Tudor and Jacobean Tournaments, Sheridan House, ISBN 978-0-911378-75-7

- Clayton, Eric, Justin Fyles, Erik DeVolder, Jonathan E.H. Hayden. "Arms and Armor of the Medieval Knight." Arms and Armor of the Medieval Knight (2008): 1–115. Web. 8 Mar. 2016.

- Clephan, R. Coltman. The Medieval Tournament. New York: Dover Publications, 1995. Print.

External links

- The Chronicles of Froissart excerpts from 1849 edition of the Thomas Johnes translation (1805).

- Tales from Froissart excerpts from 1849 edition of the Thomas Johnes translation (1805).

- From Lance to Pistol: The Evolution of Mounted Soldiers from 1550 to 1600 (myArmoury.com article)

- "Tudor Joust Game (free, educational, online)". British Galleries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- Giostra Del Saracino, Arezzo Archived 20 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- History of Jousting (middle-ages.org.uk)

- U.S.A. Hall of Fame

- Maryland Jousting Tournament Association

- Sport jousting in the U.S.A.

- Capwell, Tobias (27 April 2017). Deeds Not Words: The History of Modern Jousting. The Wallace Collection. Video on YouTube.