Friedrich Ebert

Friedrich Ebert (German: [ˈfʁiːdʁɪç ˈeːbɐt] ⓘ; 4 February 1871 – 28 February 1925) was a German politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the first president of Germany from 1919 until his death in office in 1925.

Friedrich Ebert | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Ebert in 1925 | |

| President of Germany | |

| In office 11 February 1919 – 28 February 1925 | |

Minister President (1919) | Philipp Scheidemann Gustav Bauer |

Chancellor (1919–1925) | |

| Preceded by | Wilhelm II (as Emperor) |

| Succeeded by | Paul von Hindenburg |

| Head of government of Germany | |

| De facto 9 November 1918 – 13 February 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Max von Baden (as Chancellor) |

| Succeeded by | Philipp Scheidemann (as Minister President) |

| Leader of the Social Democratic Party | |

| In office 20 September 1913 – 15 June 1919 | |

| Preceded by | August Bebel |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Member of the Reichstag for Düsseldorf 2 | |

| In office 7 February 1912 – 9 November 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Friedrich Linz |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 February 1871 Heidelberg, Grand Duchy of Baden, German Empire |

| Died | 28 February 1925 (aged 54) Berlin, Weimar Republic |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including Friedrich Jr. |

| Signature |  |

Ebert was elected leader of the SPD on the death in 1913 of August Bebel. In 1914, shortly after he assumed leadership, the party became deeply divided over Ebert's support of war loans to finance the German war effort in World War I. A moderate social democrat, Ebert was in favour of the Burgfrieden, a political policy that sought to suppress squabbles over domestic issues among political parties during wartime in order to concentrate all forces in society on the successful conclusion of the war effort. He tried to isolate those in the party opposed to the war and advocated a split.

Ebert was a pivotal figure in the German Revolution of 1918–19. When Germany became a republic at the end of World War I, he became its first chancellor. His policies at that time were primarily aimed at restoring peace and order in Germany and suppressing the left, to establish a democracy. To accomplish these goals, he allied himself with conservative and nationalistic political forces, in particular the leadership of the military under General Wilhelm Groener and the right-wing Freikorps. With their help, Ebert's government crushed a number of liberal, socialist, communist and anarchist uprisings as well as those from the right, including the Kapp Putsch, a legacy that has made him a controversial historical figure.

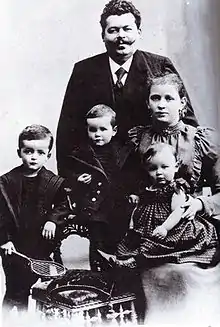

Early life

Ebert was born in Heidelberg in the Grand Duchy of Baden, on 4 February 1871, shortly after the creation of the German Empire, the seventh of nine children of the tailor Karl Ebert (1834–1892) and his wife Katharina (née Hinkel; 1834–1897). Three of his siblings died at a young age.[1][2][3][4] Although he wanted to attend university, this proved impossible due to his family's lack of funds.[5] Instead, he trained as a saddle-maker from 1885 to 1888.[1] After he became a journeyman in 1889 he travelled, according to the German custom, from place to place in Germany, seeing the country and learning fresh details of his trade. In Mannheim, he was introduced by an uncle to the Social Democratic Party, joining it in 1889.[5][6] Although Ebert studied the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, he was less interested in ideology than in practical and organisational issues that would improve the lot of the workers then and there.[5] Ebert was placed on a police "black list" due to his political activities, so he kept changing his place of residence. Between 1889 and 1891, he lived in Kassel, Braunschweig, Elberfeld-Barmen, Remscheid, Quakenbrück and Bremen, where he founded and chaired local chapters of the Sattlerverband (Association of Saddlers).[1]

After settling in Bremen in 1891, Ebert made a living doing odd jobs.[1] In 1893, he obtained an editorial post on the socialist Bremer Bürgerzeitung. In May 1894, he married Louise Rump (1873–1955), daughter of a manual labourer, who had been employed as a housemaid and in labelling boxes and who was active in union work.[1][7] He then became a pub owner that became a centre of socialist and union activity and was elected party chairman of the Bremen SPD.[1] In 1900, Ebert was appointed a trade-union secretary (Arbeitersekretär) and elected a member of the Bremer Bürgerschaft (comitia of citizens) as the representative of the Social Democratic Party.[8] In 1904, Ebert presided over the national convention of the party in Bremen and became better known to a wider public.[1] He became a leader of the "moderate" wing of the Social Democratic Party and in 1905 Secretary-General of the SPD, at which point he moved to Berlin.[5] At the time, he was the youngest member of the Parteivorstand (party executive).[7]

Meanwhile, Ebert had run for a seat in the Reichstag (parliament of Germany) several times in constituencies where the SPD had no chance of winning: 1898 Vechta (Oldenburg), 1903 and 1906 Stade (Province of Hanover).[7] However, in 1912, he was elected to the Reichstag for the constituency of Elberfeld-Barmen (today part of Wuppertal).[1] This was the election that also made the SPD the strongest party in the Reichstag with 110 out of a total of 397 members, surpassing the Centre Party. On the death of August Bebel on 13 August 1913, Ebert was elected as joint party chairman at the convention in Jena on 20 September with 433 out of 473 votes.[5][6] His co-chairman was Hugo Haase.[1]

World War I

When the July Crisis of 1914 erupted, Ebert was on vacation. After war was declared in early August, Ebert travelled to Zürich with party treasurer Otto Braun and the SPD's money to be in a position to build up a foreign organisation if the SPD should be outlawed in the German Empire. He returned on 6 August and led the SPD Reichstag members to vote almost unanimously in favour of war loans, accepting that the war was a necessary patriotic, defensive measure, especially against the autocratic regime of the Tsar in Russia.[9] In January 1916, Haase resigned.[1] Under the leadership of Ebert and other "moderates" such as Philipp Scheidemann, the SPD party participated in the Burgfrieden, an agreement among the political parties in the Reichstag to suppress domestic policy differences for the duration of the war in order to concentrate the energies of the country solely on bringing the conflict to a successful conclusion for Germany. This positioned the party in favour of the war with the aim of a compromise peace, a stance that eventually led to a split in the SPD, with those radically opposed to the war leaving the SPD in early 1917 to form the Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, or USPD. Similar policy disputes caused Ebert to end his parliamentary alliance with several left-wing members of the Reichstag and start to work closely with the Centre Party and the Progress Party in 1916.[5] Later those kicked out by Ebert called themselves "Spartacists". Beginning in 1916, Ebert shared the leadership of his Reichstag delegates with Scheidemann.[5] Although he opposed a policy of territorial gains secured through military conquest on the western front (aside from Luxembourg which was German speaking and could be easily incorporated), Ebert supported the war effort overall as a defensive struggle.[5] Ebert experienced the traumatic loss of having two of his four sons killed in the war: Heinrich died in February 1917 in Macedonia, whereas Georg was killed in action in May 1917 in France.[7] In June 1917, a delegation of social democrats led by Ebert travelled to Stockholm for talks with socialists from other countries about a conference that would have sought to end the war without any annexations of territory on the western front except for Luxembourg and giving back most of Alsace and Loraine with blessings from the German government. The initiative failed, however.[7]

In January 1918, when the workers in munition factories in Berlin went on strike, Ebert joined the strike leadership, but worked hard to get the strikers back to work.[5] He was pilloried by a few politicians from the extremist left as a "traitor to the working class", and from the right as a "traitor to the fatherland".[1]

Revolution of 1918–19

Parliamentisation

As the war continued, the military Supreme Command (OHL), nominally headed by Paul von Hindenburg, but effectively controlled by his subordinate Erich Ludendorff, became the de facto ruler of Germany.[10]: 19–20 When it became clear that the war was lost in late summer and fall of 1918, Ludendorff started to favour the "parliamentisation" of the German Empire, i.e. a transfer of power to those parties that held the majority in the Reichstag (SPD, Centre Party and Progress Party). The goal was to shift the blame for the military defeat from the OHL to the politicians of the majority parties.[10]: 25–26

On 29 September 1918, Ludendorff suddenly informed Paul von Hintze, the German Foreign Minister, that the Western Front could collapse at any moment and that a ceasefire had to be negotiated without delay. However, he suggested that the request for the ceasefire should come from a new government sanctioned by the Reichstag majority. In his view, a "revolution from above" was needed. Chancellor Georg von Hertling and Kaiser Wilhelm II agreed, although the former resigned.[10]: 36–40 Scheidemann and a majority of SPD deputies were opposed to joining "a bankrupt enterprise", but Ebert convinced his party, arguing that "we must throw ourselves into the breach" and "it is our damned duty to do it".[10]: 44–45 In early October, the Kaiser appointed a liberal, Prince Maximilian of Baden, as chancellor to lead peace negotiations with the Allies. The new government for the first time included ministers from the SPD: Phillip Scheidemann and Gustav Bauer. The request for a ceasefire went out on 4 October.[10]: 44 On 5 October, the government informed the German public about these events. However, there was then a delay, as the American President Wilson initially refused to agree to the ceasefire. His diplomatic notes seemed to indicate that the changes to the German government were insufficient and the fact that Wilhelm II remained head of state was a particular obstacle.[10]: 52–53 Ebert did not favour exchanging the monarchy for a republic, but like many others, he was worried about the danger of a socialist revolution, which seemed more likely with every day that passed. On 28 October, the constitution was changed to make the chancellor dependent on the confidence of the Reichstag rather than the emperor. At this point, the majority parties of the Reichstag, including Ebert's SPD, were quite satisfied with the state of affairs; what they now needed was a period of calm to deal with the issue of negotiating an armistice and a peace treaty.[11]: 6

November Revolution

The plans of the new German government were thrown into disarray when a confrontation between officers and crews on board the German fleet at Wilhelmshaven on 30 October set in motion a train of events that would result in the German Revolution of 1918–19 that spread over a substantial part of the country over the next week.[10]: 59–72 Against the backdrop of a country falling into anarchy, the SPD led by Ebert on 7 November demanded a more powerful voice in the cabinet, an extension of parliamentarism to the state of Prussia and the renunciation of the throne by both the Emperor and his oldest son, Crown Prince Wilhelm. Ebert had favoured retaining the monarchy under a different ruler, but at this time told Prince Maximilian von Baden, "If the Kaiser does not abdicate, the social revolution is inevitable. But I do not want it, I even hate it like sin."[12] On the left, the Spartacists (numbering around 100 in Berlin) and a group of around 80 to 100 popular labour leaders from Berlin known as Revolutionary Stewards (Revolutionäre Obleute) prepared for a revolution in the capital.[11]: 7

On 9 November, the revolution reached Berlin as the larger companies were hit by a general strike called by the Spartacists and the Revolutionary Stewards, but also supported by the SPD and the mainstream unions. Workers' and soldiers' councils were created, and important buildings occupied. As the striking masses marched on the centre of Berlin, the SPD, afraid of losing its influence on the revolution, announced that it was resigning from the government of Prince Maximilian.[11]: 7

Meanwhile, Prince Maximilian had failed to convince Emperor Wilhelm II, who was at the army headquarters at Spa, Belgium, of the need to abdicate. Wilhelm had resigned himself to the loss of the imperial crown, but still thought he could remain king of Prussia. However, under the imperial constitution, the imperial crown was tied to the Prussian crown. When Maximilian failed to convince him of the unreality of giving up one crown and not the other, he unilaterally and untruthfully announced that Wilhelm had in fact abdicated both titles and that the Crown Prince had agreed to relinquish his right of succession.[11]: 7 Shortly thereafter, the SPD leadership arrived at the chancellery and Ebert asked Prince Maximilian to hand over the government to him.[11]: 7 After a short meeting of the cabinet, the chancellor resigned and, in an unconstitutional move, handed his office over to Ebert, who thus became Chancellor of Germany and Minister President of Prussia. He was the first socialist, the second politician and the second commoner to hold either office.[10]: 87 Ebert left the government of Prince Maximilian mostly unchanged, but appointed SPD operatives for the Prussian Minister of War and for the military commander of the Berlin area.[11]: 7

Ebert's first action as chancellor was to issue a series of proclamations asking the people to remain calm, stay out of the streets and to restore peace and order. It failed to work. Ebert then had lunch with Scheidemann at the Reichstag and, when asked to do so, refused to speak to the masses gathered outside. Scheidemann however seized upon the opportunity,[10]: 88–90 and in hopes of forestalling whatever the Communist leader Karl Liebknecht planned to tell his followers at the now-former royal palace, proclaimed Germany a republic.[13] A furious Ebert promptly reproached him: "You have no right to proclaim the Republic!" By this he meant that the decision was to be left to an elected national assembly, even if that decision might be the restoration of the monarchy.[11]: 7–8 Later that day, Ebert even asked Prince Maximilian to stay on as regent, but was refused.[10]: 90

Since Wilhelm II had not actually abdicated on 9 November, Germany legally remained a monarchy until the Emperor signed his formal abdication on 28 November.[10]: 92 But when Wilhelm handed over supreme command of the army to Paul von Hindenburg and left for the Netherlands on the morning of 10 November, the country was effectively without a head of state.[11]: 8

An entirely Socialist provisional government based on workers' councils was about to take power under Ebert's leadership. It was called the Council of the People's Deputies (Rat der Volksbeauftragten). Ebert found himself in a quandary. He had succeeded in bringing the SPD to power, and he was now in a position to put into law social reforms and improve the lot of the working class. Yet as a result of the revolution, he and his party were forced to share power with those on the left whom he despised: the Spartacists and the Independents.[10]: 96 In the afternoon of 9 November, he grudgingly asked the USPD to nominate three ministers for the future government. Yet that evening a group of several hundred followers of the Revolutionary Stewards occupied the Reichstag building and were holding an impromptu debate. They called for the election of soldiers' and workers' councils the next day with an eye to name a provisional government: the Council of the People's Deputies.[10]: 100–103 In order to keep control of events and against his own anti-revolutionary convictions, Ebert decided that he needed to co-opt the workers' councils and thus become the leader of the revolution while at the same time serving as the formal head of the German government.

On 10 November, the SPD, led by Ebert, managed to ensure that a majority of the newly elected workers' and soldiers' councils came from among their own supporters. Meanwhile, the USPD agreed to work with him and share power in the Council of the People's Deputies, the new revolutionary government. Ebert announced the pact between the two socialist parties to the assembled councils who were eager for a unified socialist front and approved the parity of three members each coming from SPD and USPD.[10]: 109–119 Ebert and Haase for the USPD were to be the joint chairmen.[1] That same day, Ebert received a telephone call from OHL chief of staff Wilhelm Groener, who offered to cooperate with him. According to Groener, he promised Ebert the loyalty of the military in exchange for some demands: a fight against Bolshevism, an end to the system of soldiers' and workers' councils, a national assembly and a return to a state of law and order.[10]: 120 This initiated a regular communication between the two that involved daily telephone conversations over a secret line, according to Groener.[10]: 121 The agreements between the two became known as the Ebert–Groener pact.[14]

Council of the People's Deputies

In domestic policy, a number of social reforms were quickly introduced by the Council of the People's Deputies under Ebert's leadership, including unemployment benefits,[15] the eight-hour workday, universal suffrage for everyone over the age of 20,[15] the right of farmhands to organise,[16] and increases in workers' old-age, sick and unemployment benefits.[17]

A decree of 12 November 1918 established the Reich Office for Economic Demobilization,[18] with the purpose of carrying the German economy over "to peace conditions". On 22 November 1918, a regulation was issued by the Reich Food Office for election to "peasants' and workers' councils" which were subscribed to "by all agricultural associations".[19] On 23 November 1918, the Reich Office for Economic Demobilization issued twelve regulations which set forth rules governing duration of the working day, sick leaves, paid vacations, "and other aspects of labour relations within the German economy".[20] A decree of the Office for Economic Demobilization made on 9 December 1918 provided that the state governments "should require the communes and communal unions to establish departments for general vocational guidance and for placement of apprentices".[21]

On 23 November 1918, an Order was introduced prohibiting work in bakeries between the hours of 10 p.m. and 6 am.[22] In December 1918, the income limit for entitlement to health insurance coverage was raised from 2,500 to 5,000 marks.[23] The right of free assembly and association, which was extended even to government workers and officials, was made universal, and all censorship was abolished. The Gesindeordnung (servant's ordinance promulgated in Prussia in 1810) was revoked, and all discriminatory laws against agricultural workers were removed.[24] A Provisional Order on 24 January 1919 provided various rights for agricultural workers.[25] In addition, provisions for labour protection (suspended during the war) were restored,[24] and a number of decrees were issued establishing freedom of the press, religious freedom, and freedom of speech, and amnesty of political prisoners.[26] Protections for homeworkers were also improved,[27][28] and housing provision was increased.[29]

A decree of 23 December 1918 regulated wage agreements, laying down that a wage agreement that had been concluded in any branch of employment between the competent trade union authority and the competent employers' authority had absolute validity, meaning that no employer could enter into any other agreement of his own initiative. In addition, an organisation of arbitral courts was set up to decide all disputes. A decree of 4 January 1919 compelled employers to reinstate their former labourers on demobilisation, while measures were devised to safeguard workers from arbitrary dismissal. Workers who felt that they had been treated unfairly could appeal to an arbitration court, and in case of necessity the demobilisation authorities "had the power to determine who should be dismissed and who should be retained in employment".[30] On 29 November 1918, the denial of voting rights to welfare recipients was repealed.[31]

A government proclamation of December 1918 ordered farmers to re-employ returning soldiers "at their former working place and to provide work for the unemployed",[19] while an important decree was issued that same month in support of Jugendpflege (youth welfare).[32] In December 1918, the government granted provisionally the continuation of a maternity allowance introduced during the Great War,[33] while a decree issued in January 1919 mandated the employment of disabled veterans.[34] A Settlement Decree was issued by the government on 29 January 1919[35] "concerning the acquisition of land for the settlement of workers on the land"[36] that foresaw "the possibility of expropriating estates over 100 hectares to facilitate settlement". However, only just over 500,000 hectares were freed by 1928, benefiting 2.4% of the farming population.[37]

In addition, Ebert's government got food supplies moving again[29] and issued various decrees related to the promotion of civil aviation[38] and restrictions on firearm possession.[39]

Civil war

In the weeks following the creation of the Council of the People's Deputies, Ebert and the leadership of the SPD sided with the conservative and nationalistic elements in German society (the civil servants, the armed forces, the police, the judiciary) against the forces of the revolution. The latter wanted to eliminate the challenge to the existing order posed by the workers' councils as soon as possible.[10]: 129 Yet the majority of those in the workers' and soldiers' councils viewed themselves as supporters of the government. It was only the Spartacists who wanted a dictatorship of the workers.[10]: 130 Ebert and Groener worked out a "program" to restore order in Berlin by having army units returning from the Western Front move in and disarm all paramilitary forces from 10 to 15 December.[10]: 132–134 However, after the ten divisions had arrived, rather than remaining as a cohesive force, they dispersed. On 16 December, the Reichsrätekongress (congress of councils) met in Berlin and set the date for elections to the National Assembly for 19 January 1919. However, it also passed a resolution that was aimed at ensuring that the military would be under the strict control of the civilian government, i.e. the Council of the People's Deputies. It also called for a powerful position of the soldiers' councils vis-à-vis the professional officer corps. This was unacceptable to the leaders of the military and the OHL began to establish volunteer regiments in the Berlin area.[10]: 136–138

Fighting erupted on 24 December on the Schlossplatz in Berlin (the Skirmish of the Berlin Schloss). On 23 December, dissatisfied members of the Navy occupied the chancellery and put the Peoples' Deputies under house arrest. Ebert asked the OHL for help over the phone and troops assembled on the outskirts of the capital. During the night, Ebert then ordered these troops to attack, which they did in the morning of 24 December. When the fighting stopped in the afternoon, the Navy forces held the field, but they returned to their barracks, ending the crisis.[10]: 139–147 As a result of this event, which Karl Liebknecht called "Ebert's Bloody Christmas", the USPD members left the Council of the Peoples' Deputies on 29 December. The next day, SPD members Gustav Noske and Rudolf Wissell took their place and from that point on, government communiques were signed Reichsregierung (i.e. federal government) instead of "Council of the Peoples' Deputies".[10]: 151–152 That same day, the Spartacists severed their remaining links with the USPD and set themselves up as the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).[10]: 152

The week of 5–12 January 1919 became known as "Spartacus week", but historians view this as a misnomer.[10]: 155 The "Spartacist uprising" was more an attempt by the Berlin workers to regain what they thought had been won in the November revolution and what they now seemed to be in the process of losing. The trigger was a trivial event: the head of the Berlin police, a member of the USPD, refused to accept his dismissal.[10]: 155 The USPD called for a demonstration of solidarity, but was itself surprised by the reaction as hundreds of thousands, many of them armed, gathered in the city centre on 5 January. They seized the newspapers and railway stations. Representatives from the USPD and KPD decided to topple the Ebert government. However, the next day, the gathered masses did not seize government buildings, as the expected support from the military did not materialize. Ebert started to negotiate with the leaders of the uprising, but simultaneously prepared for military action. Noske was made commander of the Freikorps (a right-wing paramilitary organization) and Ebert worked to mobilise the regular armed forces of the Berlin area on the government's side.[10]: 162 From 9 to 12 January on Ebert's orders, regular forces and Freikorps successfully and bloodily suppressed the uprising.[10]: 163–168

President of Germany

In the first German presidential election, held on 11 February 1919, five days after the Nationalversammlung (constituent assembly) convened in Weimar, Ebert was elected as provisional president of the German Republic.[40] He remained in that position after the new constitution came into force and was sworn in as Reichspräsident on 21 August 1919.[1] He was Germany's first-ever democratically elected head of state, and was also the first commoner, the first social democrat, the first civilian, and the first person from a proletarian background to hold that position. In the whole time of the unified German Reich's existence from 1871 to 1945, he was also the only head of state who was unequivocally committed to democracy.[7]

.jpg.webp)

One of Ebert's first tasks as president was to deal with the Treaty of Versailles. When the treaty's terms became public on 7 May 1919, it was cursed by Germans of all political shades as an onerous "Diktat", particularly because Germany had essentially been handed the treaty and told to sign without any negotiations. Ebert himself denounced the treaty as "unrealizable and unbearable".[41] However, Ebert was well aware of the possibility that Germany would not be in a position to reject the treaty. He believed that the Allies would invade Germany from the west if Germany refused to sign. To appease public opinion, he asked Hindenburg if the army was capable of holding out if the Allies renewed hostilities. He promised to urge rejection of the treaty if there was even the remote possibility that the army could make a stand. Hindenburg, with some prodding from Groener, concluded that the army was not capable of resuming the war even on a limited scale. Rather than tell Ebert himself, he dispatched Groener to deliver the Army's conclusion to the president. Ebert thus advised the National Assembly to approve the treaty, which it did by a large majority on 9 July.[42][41]

The government's fight against Communist forces, as well as recalcitrant socialists, went on after Ebert became president. From January to May 1919, in some areas through the summer, civil war in Germany continued. Since 19 January elections had returned a solid majority for the democratic parties (SPD, Zentrum, and DDP), Ebert felt that the revolutionary forces had no legitimacy left. He and Noske now used the same forces they had earlier employed in Berlin on a national scale to dissolve the workers' councils and to restore law and order.[10]: 183–196

In March 1920, during the right-wing Kapp Putsch by some Freikorps elements, the government, including Ebert, had to flee from Berlin. However, a refusal by civil servants to accept the self-declared government and a general strike called by the legitimate cabinet led to the collapse of the putsch. After it ended, striking workers in the Ruhr region refused to return to work. Led by members of the USPD and the KPD, they presented an armed challenge to the authority of the government. The government then sent Reichswehr and Freikorps troops to quell the Ruhr Uprising by force.

To avoid an election campaign at a critical time, the Reichstag extended his term of office on 24 October 1922 until 25 June 1925, with a qualified majority vote that changed the constitution.[1][5]

As president, Ebert appointed centre-right figures like Wilhelm Cuno and Hans Luther as Chancellor and made rigorous use of his wide-ranging powers under Article 48 of the Weimar constitution. For instance, he used Article 48 powers to deal with the Kapp Putsch and the Beer Hall Putsch.[5] Through 1924, he used the presidency's emergency powers a total of 134 times.[43]: 135

After the civil war, he changed his politics to a "policy of balance" between the left and the right, between the workers and the owners of business enterprises. In that endeavor, he followed a policy of brittle coalitions. This resulted in some problems, such as the acceptance, during the crisis of 1923, by the SPD of longer working hours without extra compensation while the conservative parties ultimately rejected the other element of the compromise, the introduction of special taxes for the rich.

Death

Ebert suffered from gallstones and frequent bouts of cholecystitis. Vicious attacks by Ebert's right-wing adversaries, including slander and ridicule, were often condoned or even supported by the judiciary when Ebert sought redress through the court system. The constant necessity to defend himself against those attacks also undermined his health. In December 1924, a court in Magdeburg fined a journalist who had called Ebert a "traitor to his country" for his role in the January 1918 strike, but the court also said that, in terms of strict legalism, Ebert had in fact committed treason.[5] These proceedings prevented him from seeking medical help for a while, as he wanted to be available to give evidence.[5]

Ebert became acutely ill in mid-February 1925 from what was believed to be influenza.[44] His condition deteriorated over the following two weeks, and at that time he was thought to be suffering from another episode of gallbladder disease.[44] He became acutely septic on the night of 23 February and underwent an emergency appendectomy (which was performed by August Bier) in the early hours of the following day for what turned out to be appendicitis.[44] Four days later, he died of septic shock, aged 54.[45]

Ebert was buried in Heidelberg. Several high-ranking politicians and a trade union leader made speeches at his funeral, as did a Protestant minister: Hermann Maas, pastor at the Church of the Holy Spirit in Heidelberg (which until the 1930s was used by both Lutheran and Catholic congregations). By thus taking part in the obsequies, Maas caused something of a scandal in his church and among political conservatives, because Ebert had been an outspoken atheist (although Ebert was baptised a Catholic, he had officially abandoned Christian observance many years before his last illness).[46]

Friedrich Ebert Foundation

Ebert's policy of balancing the political factions during the Weimar Republic is seen as an important archetype in the SPD. Today, the SPD-associated Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Germany's largest and oldest party-affiliated foundation, which, among other things, promotes students of outstanding intellectual ability and personality, is named after Ebert.

Some historians have defended Ebert's actions as unfortunate but inevitable if the creation of a socialist state on the model that had been promoted by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and the communist Spartacists was to be prevented. Leftist historians like Bernt Engelmann as well as mainstream ones like Sebastian Haffner on the other hand, have argued that organized communism was not yet politically relevant in Germany at the time.[47] However, the actions of Ebert and his Minister of Defense, Gustav Noske, against the insurgents contributed to the radicalization of the workers and to increasing support for communistic ideas.

Although the Weimar constitution (which Ebert signed into law in August 1919[48]) provided for the establishment of workers' councils on different levels of society, they did not play a major part in the political life of the Weimar Republic. Ebert always regarded the institutions of parliamentary democracy as a more legitimate expression of the will of the people; workers' councils, as a product of the revolution, were only justified in exercising power for a transitive period. "All power to all the people!" was the slogan of his party, in contrast to the slogan of the far left, "All power to the (workers') councils!".[11]

In Ebert's opinion only reforms, not a revolution, could advance the causes of democracy and socialism. He therefore has been called a traitor by leftists, who claim he paved the way for the ascendancy of the far-right and even of Adolf Hitler, whereas those who think his policies were justified claim that he saved Germany from Bolshevik excesses in forming a democracy.

Literature

- Wolfgang Abendroth: "Friedrich Ebert". In: Wilhelm von Sternburg: Die deutschen Kanzler. Von Bismarck bis Kohl. Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-7466-8032-8, pp. 145–159.

- Friedrich Ebert. Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit. Begleitband zur ständigen Ausstellung in der Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte, edited by Walter Mühlhausen. Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg 1999, ISBN 3-933257-03-4.

- Köhler, Henning: Deutschland auf dem Weg zu sich selbst. Eine Jahrhundertgeschichte. Hohenheim Verlag, Stuttgart/Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-89850-057-8.

- Eberhard Kolb (ed.): Friedrich Ebert als Reichspräsident – Amtsführung und Amtsverständnis. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, München 1997, ISBN 3-486-56107-3.[49] Containing:

- Richter, Ludwig: Der Reichspräsident bestimmt die Politik und der Reichskanzler deckt sie: Friedrich Ebert und die Bildung der Weimarer Koalition.

- Mühlhausen, Walter: Das Büro des Reichspräsidenten in der politischen Auseinandersetzung.

- Kolb, Eberhard: Vom "vorläufigen" zum definitiven Reichspräsidenten. Die Auseinandersetzung um die "Volkswahl" des Reichspräsidenten 1919–1922.

- Braun, Bernd: Integration kraft Repräsentation – Der Reichspräsident in den Ländern.

- Hürten, Heinz: Reichspräsident und Wehrpolitik. Zur Praxis der Personalauslese.

- Richter, Ludwig: Das präsidiale Notverordnungsrecht in den ersten Jahren der Weimarer Republik. Friedrich Ebert und die Anwendung des Artikels 48 der Weimarer Reichsverfassung.

- Mühlhausen, Walter: Reichspräsident und Sozialdemokratie: Friedrich Ebert und seine Partei 1919–1925.

- Georg Kotowski (1959), "Friedrich Ebert", Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German), vol. 4, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 254–256; (full text online)

- Mühlhausen, Walter:Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925. Reichspräsident der Weimarer Republik. Dietz, Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-8012-4164-5. (Rezension von Michael Epkenhans Archived 14 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine In: Die Zeit. 1 February 2007)

- Mühlhausen, Walter: Die Republik in Trauer. Der Tod des ersten Reichspräsidenten Friedrich Ebert. Stiftung Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte, Heidelberg 2005, ISBN 3-928880-28-4.

References

- "Biografie Friedrich Ebert (German)". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Biografie Friedrich Ebert (German)". Bayerische Nationalbibliothek. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Dennis Kavanagh (1998). "Ebert, Friedrich". A Dictionary of Political Biography. Oxford: OUP. p. 157. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- "Friedrich Ebert: Leben 1871–1888 (German)". Stiftung Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- Herzfeld, Hans, ed. (1963). Geschichte in Gestalten:1:A-E (German). Fischer, Frankfurt. pp. 335–336.

- Harenberg Personenlexikon: Ebert, Friedrich. Harenberg Lexikon Verlag, Dortmund. 2000. pp. 274–275. ISBN 3-611-00893-1.

- "Friedrich Ebert (1871–1925).Vom Arbeiterführer zum Reichspräsidenten (German)". Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

- Eberhard Pikart: Der deutsche Reichstag und der Ausbruch des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Der Staat 5, 1966, pp 58 ff

- Haffner, Sebastian (2002). Die deutsche Revolution 1918/19 (German). Kindler. ISBN 3-463-40423-0.

- Sturm, Reinhard (2011). "Weimarer Republik, Informationen zur politischen Bildung, Nr. 261 (German)". Informationen zur Politischen Bildung. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. ISSN 0046-9408. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Reichspräsident-Friedrich-Ebert-Gedenkstätte". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Kuhn, Gabriel (2012). All Power to the Councils!: A Documentary History of the German Revolution of 1918-19. PM Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1604861112. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "HISTORICAL EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG" (PDF).

- McEntee-Taylor, C. (2011). A Week in May 1940 & the Pencilled Message. Createspace Independent Pub. p. 330. ISBN 9781466442931.

- Fischer, R.P. (1948). Stalin and German Communism. Harvard University Press. p. 296. ISBN 9781412835015.

- The Kings Depart: The Tragedy of Germany: Versailles and the German Revolution by Richard M. Watt

- "(Nr. 6548) Anordnung über die Regelung der Arbeitszeit gewerblicher Arbeiter. Vom 23. November 1918" (PDF). 7 April 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Farm labor in Germany, 1810–1945; its historical development within the framework of agricultural and social policy by Frieda Wunderlich

- Grange, W. (2008). Cultural Chronicle of the Weimar Republic. Scarecrow Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780810859678.

- Kuczynski, R.R. (1925). Postwar Labor Conditions in Germany: March, 1925. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 185.

- "The I.L.O. Yearbook 1931" (PDF). International Labour Office. 1931. p. 200. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Companje, K.P.; Veraghtert, K.; Widdershoven, B. (2009). Two Centuries of Solidarity: German, Belgian, and Dutch Social Health Care Insurance 1770–2008. Aksant. p. 126. ISBN 9789052603445.

- Holborn, H. (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1840–1945. Princeton University Press. p. 519. ISBN 9780691007977.

- "Full text of "Technical survey of agricultural questions. Hours of work, unemployment, protection of women and children, technical agricultural education, living-in conditions, rights of association and combination, social insurance"". Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Weitz, E.D. (2013). Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400847365.

- "de/page/68/epochen-abschnitt/12/epochen". in-die-zukunft-gedacht.de. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Micha Hoffmann. "Deutsche Sozialgeschichte: Arbeitswelt 1750 – 1950". schultreff.de. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- AQA History: The Development of Germany, 1871–1925 by Sally Waller

- Arthur Rosenberg. "A History of the German Republic by Arthur Rosenberg 1936". marxists.org. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Stolleis, M. (2013). History of Social Law in Germany. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. p. 96. ISBN 9783642384547. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Dickinson, E.R. (1996). The Politics of German Child Welfare from the Empire to the Federal Republic. Harvard University Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780674688629. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Usborne, C. (1992). The Politics of the Body in Weimar Germany: Women's Reproductive Rights and Duties. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 46. ISBN 9781349122448. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Maastrichts Europees Instituut voor Transnationaal Rechtswetenschappelijk Onderzoek (1994). "Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law". Maastricht Journal of European and Comparative Law Mj. Maklu. 1. ISSN 1023-263X. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Kovan, A.S. (1972). The Reichs-Landbund and the Resurgence of Germany's Agrarian Conservatives, 1919–1923. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- International Labour Office (1921). Technical Survey of Agricultural Questions: Hours of Work, Unemployment, Protection of Women and Children, Technical Agricultural Education, Living-in Conditions, Rights of Association and Combination, Social Insurance. International Labour Office. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Hiden, J. (2014). The Weimar Republic. Taylor & Francis. p. 34. ISBN 9781317888833. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Hirschel, E.H.; Prem, H.; Madelung, G. (2004). Aeronautical Research in Germany: From Lilienthal Until Today. Springer. p. 53. ISBN 9783540406457.

- Carter, G.L. (2012). Guns in American Society: An Encyclopedia of History, Politics, Culture, and the Law. ABC-CLIO. p. 314. ISBN 9780313386701.

- Kolb, Eberhard (2005). The Weimar Republic. Psychology Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-415-34441-8. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- William Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Touchstone Edition) (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990)

- Koppel S. Pinson (1964). Modern Germany: Its History and Civilization (13th printing ed.). New York: Macmillan. p. 397 f. ISBN 0-88133-434-0.

- von Krockow, Christian (1990). Die Deutschen in ihrem Jahrhundert 1890–1990 (German). Rowohlt. ISBN 3-498-034-52-9.

- "German president has appendicitis". The Evening Record. Ellensburg, Washington: Ellensburg Daily Record. Associated Press. 24 February 1925. p. 2. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Kershaw, I (1998). Hitler, 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 267. ISBN 0393320359.

- See Walter Mühlhausen, Friedrich Ebert 1871–1925 – Reichspräsident der Weimarer Republik, pp. 977ff; Werner Keller: "Hermann Maas – Heiliggeistpfarerr und Brückenbauer" in: Gottfried Seebaß, Volker Sellin, Hans Gercke, Werner Keller, Richard Fischer (editors): Die Heiliggeistkirche zu Heidelberg 1398–1998, Umschau Buchverlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8295-6318-3, pp. 108ff.

- Bernt Engelmann: Einig gegen Recht und Freiheit. Deutsches Anti-Geschichtsbuch. 2. Teil, Bertelsmann, München 1975

- Weimar Germany by Anthony McElligott

- Kolb, E. (1997). Friedrich Ebert als Reichspräsident: Amtsführung und Amtsverständnis. de Gruyter. p. 307. ISBN 9783486561074. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

External links

- (in German) President Friedrich Ebert Memorial in Heidelberg

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Works by Friedrich Ebert at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Friedrich Ebert on the First Post-Imperial German Government, Statement of 10 November 1918

- President Friedrich Ebert's Address to the German Assembly, 7 February 1919

- President Friedrich Ebert's Address to the German Assembly, 11 February 1919

- Newspaper clippings about Friedrich Ebert in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW