Friends of Seagate Inc.

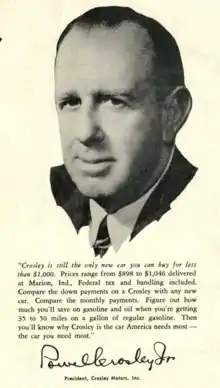

Friends of Seagate Inc. was founded in the late 1980s by Kafi Benz as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization in Sarasota, Florida. The historic preservation group lead local efforts protect historic property in the Sarasota-Bradenton area from commercial development. The group later expanded its scope to include environmental conservation. Its most notable project was the preservation of Seagate, the former home of Cincinnati, Ohio, industrialist Powel Crosley Jr. and his wife, Gwendolyn, and its later owners, Mabel and Freeman Horton. (Horton was a civil engineer who proposed the construction of the original Sunshine Skyway Bridge across Tampa Bay.) In 2002 the organization tried to secure Rus-in- Ur'be, an undeveloped parcel of land in the center of the Indian Beach Sapphire Shores neighborhood, as a local park; however, as of 2014, real estate developers intend to build condominium units at the site.

History

In the late 1980s Kafi Benz founded the Friends of Seagate, a nonprofit historic preservation organization,[1] to champion the preservation of portions of Seagate, a historic, 64-acre (26-hectare) property in Manatee County, Florida.[2][3][4]

Preservation projects

The Friends of Seagate is best known for its efforts to preserve the Seagate estate along Sarasota Bay. The bay-front property was acquired by the State of Florida in the early 1990s. The present-day, 16.5-acre (6.7-hectare) Powel Crosley Estate serves as an event rental facility.[5] A 28.4-acre (11.5-hectare) parcel of the property is the present-day site of the University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee campus.[6] Seagate's distinctive weathervane atop it tower was th inspiration for the organization's logo.

Following public acquisition of the Seagate property, the nonprofit organization's objectives expanded to include broader community development, conservation, and preservation issues that involvedg other archaeological, artistic, cultural, built and natural environmental, and historical concerns.[7] Lake Underwood, a patron to Friends of Seagate, provided much of the funding and equipment for the expansion of the organization.

Seagate

Ownership

Platted as a residential subdivision named Sea Gate in 1925, Cincinnati, Ohio, industrialist Powel Crosley Jr. acquired the property that became known as Seagate in 1929. Crosley had a two-and-a-half-story Mediterranean Revival style house, built on the site on Sarasota Bay for his wife, Gwendolyn, who died there in 1939. Crosley rarely used the home after her death and sold the property in 1947.[2][8][9]

Seagate changed ownership several times, and several unsuccessful plans were submitted for its commercial development, until a local campaign for its preservation resulted in the property's public acquisition. Subsequent owners included Mabel and Freeman Horton, who was a civil engineer who proposed the construction of the original Sunshine Skyway Bridge across Tampa Bay. The Horton family lived at Seagate from 1948 until 1977.[9][10] The Campeau Corporation of American purchased Seagate in the early 1980s for development into a condominium project, but the condominium market in Florida collapsed shortly after Campeau acquired the property and the company's plans to convert the home and auxiliary buildings into a clubhouse and headquarters of the development were never realized. However, the company was successful it its efforts to have the Crosley estate was formally added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 1983.[2][11][12]

In 1990 the State of Florida acquired the property, which was divided into two portions. The bay front residence and 16.5 acres (6.7 hectares) were overseen by Manatee County, Florida. The much larger, eastern portion of the property along Tamiami Trail was overseen by New College and University of South Florida until their separation and the resulting development of this portion into a new satellite campus for the university.

Preservation efforts

In the late 1980s Kafi Benz founded Friends of Seagate Inc., a local, nonprofit preservation organization, and initiated a campaign for Seagate's preservation. Benz and her group also began a fundraising effort for its acquisition.[13] Benz, the Friends and Seagate, and area residents successfully opposed several proposals for the property's commercial development.[14]

Prior to the property's public acquisition in the early 1990s, the property was assessed for its archaeological, architectural, biological, cultural, environmental, and historical aspects. Dudley E. DeGroot,[15] a member of the Friends of Seagate board of directors, led an archaeological survey of the area that Benz conducted and registered.[16] Jerris Foote, a fellow director with Benz of the Sarasota Alliance for Historic Preservation, Inc., also participated in the survey.. The archaeological survey was provided to Frank Perkins IV,[17] the Manatee County property appraiser, for inclusion in the assessment and proposal for Seagate's public acquisition.

Public acquisition and redevelopment

In 1990 the state of Florida acquired the property, which was divided into two parcels. The Manatee County Commission paid $1.6 million in 1991 for the bay-front residence and 16.5 acres (6.7 hectares) of land, intending to preserve and renovate the property. The present-day Crosley Estate has been restored. It is used as a meeting, conference, and event rental venue. sometimes referred to as the Crosley mansion. The estate is aided by fundraising efforts of the Crosley Estate Foundation.[5] The University of South Florida controlled 28.4 acres (11.5 hectares) of the property, which it acquired for $2 million for future expansion if a satellite campus for the Tampa-based university along Tamiami Trail.[9]

The design process for the University of South Florida's satellite campus (the present-day University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee) was extensive. Kafi Benz participated in a design charrette that lasted several days, providing tours of the property and suggesting many details to the design team. The location of the campus's three-story building is derived from a plan that Benz proposed, which included use of open space on the parcel of land in order to preserve the uplands slash pine forest that dominated the eastern portion of the property. Although Benz's initial design plan was built, the university sacrificed the pine forest to reduce costs. Instead of constructing a planned parking facility, the university created surface parking. Except for a small stand in which gopher tortoise habitat existed, most of the mature pine trees were lost to a clear-cut of the land that would become the campus parking lot. A new entrance driveway also divided a small stand of pine trees. The driveway was elevated to accommodate tunnels designed for animals to use to avoid crossing the roadway. The former wetlands on the property was excavated to create a storm-water retention area landscaped to resemble a lake. Oak seedlings were planted in the landscaped islands created among the rows of asphalt. The university projected that it would outgrow the facility within twenty years.

Wildlife habitat

An eagle nest found on the Seagate property was registered through Florida's department of environmental protection. It was designated as nest "Number Nine" for Manatee County after the state completed its assessment. Photographer Arthur E. "Mike" DeLoach, a board member of Friends of Seagate, assisted with the documentation.

In addition, the property was the subject of other environmental studies that indicated the habitat supported two populations of gopher tortoise; the concomitant animals associated with that habitat, such as indigo snakes; and the registered eagle nesting site. Other birds associated with the site include hawks, osprey, owls, woodpeckers, and waders, such as the roseate spoonbill. A great rookery of herons and egrets also took advantage of the isolated property. Horseshoe crabs used the secluded beach as a breeding location.

A small portion of the natural habitat remains to the north of the Crosley home, beyond the yacht basin. A narrow beachfront extends into the bay from a steep bank that was enlarged by fill that was dumped from dredges for access to the basin beginning in 1929. Beyond the fill are a few exotic trees introduced for flood control and landscape value, but native vegetation remains among a few invasive species. Longleaf pine as well as second growth slash pine of great age remain in undisturbed areas. Plans for potential use of the remaining portion of the property must be presented to the county government officials for review.

Rus-in-Ur'be

In November 2002 the Friends of Seagate partnered as the nonprofit environmental entity with the Sarasota municipal government as the eligible local governmental entity for a grant of $1,505,625 through the Florida Communities Trust's "Florida Forever Program," a state conservation and recreation lands acquisition grant program. The partners intended to hold the Rus In Ur'be property in the center of the Indian Beach Sapphire Shores neighborhood of Sarasota for use as a local park. The grant request was approved as part of the Series FF2 funding cycle,[18] but the partners were unable to acquire it before the land was sold for private development.[19]

The parcel of more than 11 acres (4.5 hectares) contained a wooded and undeveloped land, wetlands, a tennis court, and a Sarasota School of Architecture structure that served as a private clubhouse or recreational lounge for a bay-front home on Bay Shore Road opposite the property. (The Bay Shore Road home was sold separately from the Rus In Ur'be and held by a real estate developer.) The timber-framed clubhouse of pecky cypress included a roof with glazed blue Japanese ceramic tiles and expansive glass partitions along the western elevation, facing the tennis courts.

The clubhouse structure and the tennis courts were demolished. The property was subsequently cleared and surveyed, then platted for development with single-family homes. A private road was paved through the parcel, but no structures were built prior to the downturn of the real estate market as the speculation boom of the 1990s and 2000s collapsed. Other development projects have been proposed for the vacant parcel of land, but local residents opposed them. Some of the neighborhood residents still wanted the remaining undeveloped property to be a community park; however, a real estate developer purchased two parcels of vacant land in 2014, intending to build single-family homes and condominium units on the sites.[20]

Notes

- "Tax Exempt Organizations in Zip Code 34230". Nonprofitdata.com. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- Zimny, Michael and Sarah Kearns (January 21, 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory ––Nomination Form: Seagate" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Caranna, Kenwyn, and Carlos Galarza (August 15, 1990). "Historic But Dilapidated Estate Wins Reprive". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: A1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Unknown title". Sarasota Magazine. May 1, 1992.

- "Powel Crosley Estate: Rental Info and Rates". Bradenton Area Convention and Visitor's Bureau. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Facilities planning and management". University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Listing in Florida Administrative Weekly, volume 28, number 50, State of Florida, December 13, 2002 documenting participation in environmental preservation through a $1.5 million acquisition grant to Friends of Seagate in partnership with local city government to purchase land for a park in the Indian Beach Sapphire Shores neighborhood in Sarasota

- LaHurd, Jeff (November 15, 2015). "Powel Crosley, Jr. remembered as a visionary". Sarasota Herald Tribune. Sarasota, Florida: B-1. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Sullebarger, Beth (December 17, 2008). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Pinecroft" (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "The Road Not Taken: The History of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge" (PDF). University of South Florida. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- Galarza, Carlos (September 20, 1990). "Campeau's Bay Front Land Remains in Real Estate Limbo". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: B1publisher =.

- The unusual listing included all of the remaining 45 acres (18 hectares) of the property. Most historic listings only include structures. See Galarza, Carlos (September 20, 1990). "Campeau's Bay Front Land Remains in Real Estate Limbo". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: B1.

- Sarasota Magazine, May 1, 1992

- Caranna, Kenwyn and Galarza, Carlos (August 15, 1990). "Historic But Dilapidated Estate Wins Reprive". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: A1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) See also: Caranna, Kenyn (November 30, 1990). "Eagle Find Has Growth Foes Flying High". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: B1. - "Dr. Dudley E. DeGroot". Florida USA Obituaries. December 10, 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-04-02. Retrieved May 14, 2018. See also: Santee, Amy L. (December 12, 2012). "Dudley E. DeGroot, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, 1927-2012". Anthropologizing blog. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2018. Also:"Dudley Edward DeGroot: Obituary". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa, Florida. December 12, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2018. Also: Meacham, Andrew (December 19, 2012). "Eckerd professor, Navy Reserve Rear Adm. Dudley DeGroot dies at 85". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Benz was listed as a contributor to 0An Historic Resources Survey of the Coastal Zone of Sarasota County, Florida, prepared for the Sarasota County Board of County Commissioners, Sarasota County Department of Natural Resources, and the Sarasota County Department of Historical Resources by the University of South Florida Department of Anthropology, Tampa, Florida for the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation per CM.235 Agreement for Cultural Resources Management; March 1990, pp. 5, 210–13. "...A great deal of information was generously shared by colleagues and concerned Sarasota County residents. We wish to acknowledge the special contributions of the following: ... Kafi Benz, Dudley deGroot ..." (p. 5.)

- "Frank Perkins IV and the Manatee County Historical Records Library". Digital Collection. Manatee County Public Library System. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Notice of Project Approval and Funding" (PDF). Florida Administrative Weekly. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of State. 28 (50): 5538. December 13, 2002. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Parks and Open Space 2002 Funding Status Report, State of Florida, Florida Forever Cycle FF2, Florida Communities Trust - Department of Community Affairs, 2002.

- John Hielscher (July 14, 2014). "Indian Beach development to resume". Herald-Tribune. Sarasota, Florida. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

References

- Caranna, Kenwyn, and Carlos Galarza (August 15, 1990). "Historic But Dilapidated Estate Wins Reprive". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: A1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Dr. Dudley E. DeGroot". Florida USA Obituaries. December 10, 2012. Archived from the original on 2016-04-02. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Dudley Edward DeGroot: Obituary". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa, Florida. December 12, 2012.

- "Facilities planning and management". University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Frank Perkins IV and the Manatee County Historical Records Library". Digital Collection. Manatee County Public Library System. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- Galarza, Carlos (September 20, 1990). "Campeau's Bay Front Land Remains in Real Estate Limbo". Bradenton Herald. Bradenton, Florida: B1.

- Hielscher, John (July 14, 2014). "Indian Beach development to resume". Herald-Tribune. Sarasota, Florida. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- LaHurd, Jeff (November 15, 2015). "Powel Crosley Jr. remembered as a visionary". Herald-Tribune. Sarasota, Florida: B-1. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- Meacham, Andrew (December 19, 2012). "Eckerd professor, Navy Reserve Rear Adm. Dudley DeGroot dies at 85". Tampa Bay Times. Tampa, Florida. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Notice of Project Approval and Funding" (PDF). Florida Administrative Weekly. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Department of State. 28 (50): 5538. December 13, 2002. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- "Powel Crosley Estate: Rental Info and Rates". Bradenton Area Convention and Visitor's Bureau. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "The Road Not Taken: The History of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge" (PDF). University of South Florida. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- Santee, Amy L. (December 12, 2012). "Dudley E. DeGroot, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, 1927-2012". Anthropologizing. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- Sullebarger, Beth (December 17, 2008). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Pinecroft" (PDF). U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- "Tax Exempt Organizations in Zip Code 34230". Nonprofitdata.com. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- "Unknown title". Sarasota Magazine. May 1, 1992.

- Zimny, Michael, and Sarah Kearns (January 21, 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory ––Nomination Form: Seagate" (pdf). National Park Service. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- The Powel Crosley Estate, official website

- University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee, official website