Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater inflow into the bay is the Hillsborough River, which flows into Hillsborough Bay in downtown Tampa. Many other smaller rivers and streams also flow into Tampa Bay, resulting in a large watershed area.

| Tampa Bay | |

|---|---|

Tampa Bay from a NASA satellite in 2006 | |

Tampa Bay | |

| Coordinates | 27°45′45″N 82°32′45″W |

| Type | harbor, estuary |

| Primary outflows | Gulf of Mexico |

| Managing agency | |

The shores of Tampa Bay were home to the Weedon Island Culture and then the Safety Harbor culture for thousands of years. These cultures relied heavily on Tampa Bay for food, and the waters were rich enough that they were one of the few Native American cultures that did not have to farm. The Tocobaga was likely the dominant chiefdom in the area when Spanish explorers arrived in the early 1500s, but there were likely smaller chiefdoms on the eastern side of the bay which were not well documented. The indigenous population had been decimated by disease and warfare by the late 1600s, and there were no permanent human settlements in the area for over a century. The United States took possession of Florida in 1821 and established Fort Brooke at the mouth of the Hillsborough River in 1824.

The communities surrounding Tampa Bay grew tremendously during the 20th century. Today, the area is home to about 4 million residents, making Tampa Bay a heavily used commercial and recreational waterway and subjecting it to increasing amounts of pollutants from industry, agriculture, sewage, and surface runoff. The bay's water quality was seriously degraded by the early 1980s, resulting in a sharp decline in sea life and decreased availability for recreational use. Greater care has been taken in recent decades to mitigate the effects of human habitation on Tampa Bay, most notably upgraded sewage treatment facilities and several sea grass restoration projects, resulting in improved water quality over time. However, occasional red tide and other algae blooms have caused concern about the ongoing health of the estuary.[1]

The term "Tampa Bay" is often used as shorthand to refer to all or parts of the Tampa Bay area, which comprises many towns and cities in several counties surrounding the large body of water. Local marketing and branding efforts (including several professional sports teams, tourist boards, and chambers of commerce) commonly use the moniker "Tampa Bay", furthering the misconception that it is the name of a particular municipality when this is not the case.[2][3]

Geography

Origin

Tampa Bay formed approximately 6,000 years ago as a brackish drowned river valley type[4] estuary with a wide mouth connecting it to the Gulf of Mexico. Prior to that time, it was a large fresh water lake, possibly fed by the Floridan Aquifer through natural springs.[5] Though the exact process of the lake-to-bay transformation is not completely understood, the leading theory is that rising sea levels following the last ice age coupled with the formation of a massive sink hole near the current mouth of the bay created a connection between the lake and the gulf.[6]

Ecology

Tampa Bay is Florida's largest open-water estuary, extending over 400 square miles (1,000 km2) and forming coastlines of Hillsborough, Manatee and Pinellas counties. The freshwater sources of the bay are distributed among over a hundred small tributaries, rather than a single river.[7] The Hillsborough River is the largest such freshwater source, with the Alafia, Manatee, and Little Manatee rivers the next largest sources. Because of these many flows into the bay, its large watershed covers portions of five Florida counties[8] and approximately 2,200 square miles (5,700 km2).

The bottom of Tampa Bay is silty and sandy, with an average water depth of only about 12 feet (3.7 m).[9] The relatively shallow water and tidal mud flats allow for large sea grass beds, and along with the surrounding mangrove-dominated wetlands, the bay provides habitat for a wide variety of wildlife. More than 200 species of fish are found in the waters of the bay, along with bottlenose dolphins and manatees, plus many types of marine invertebrates including oysters, scallops, clams, shrimp and crab. More than two dozen species of birds, including brown pelicans, several types of heron and egret, Roseate spoonbills, cormorants, and laughing gulls make their year-round home along its shores and small islands, with several other migratory species joining them in the winter. The cooler months are also when warm-water outfalls from power plants bordering the bay draw one out of every six West Indian manatees, an endangered species, to the area.[10]

Conservation

Tampa Bay was designated as an "estuary of national significance" by the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 1990. Two National Wildlife Refuges are located in Tampa Bay: Pinellas National Wildlife Refuge and the refuge on Egmont Key. Most of the islands (including several man-made islands built from dredge spoil[9][11]) and sandbars are off-limits to the public, due to their fragile ecology and their use as nesting sites by many species of birds. The Tampa Bay Estuary Program keeps watch over the Bay's health.[9]

Pollution

Tampa Bay was once teeming with fish and wildlife. People of the Safety Harbor culture lived almost entirely from mullet, shellfish, sea turtles, manatees, crabs, and other bounties harvested from the sea. As late as the early 20th century, visitors still reported huge schools of mullet swimming across the bay in such numbers that they "impeded the passage of boats".[12]

The establishment and rapid growth of surrounding communities during the 20th century caused serious damage to the bay's natural environment. Heavy harvesting of fish and other sea life, constant dredging of shipping channels, and the clearing of mangroves for shoreline development were important factors.[13] Most damaging was the discharge of waste water and other pollutants into the bay, which drastically degraded water quality.[14] The bay's health reached a low point in the 1970s. The water was so murky that sunlight could not reach the shallow bottom, reducing sea grass coverage by more than 80% compared to earlier in the century and severely impacting the marine ecosystem. Many previously common species became scarce, and bay beaches were regularly closed due to unsafe levels of bacteria and pollutants.[14][15]

Beginning in the early 1980s after federal and state legislation to improve water quality, authorities installed improved water treatment plants and tightened regulation of industrial discharge, leading to slow but steady improvement in water quality and general ecological health.[16] By 2010, measures of sea grass coverage, water clarity, and biodiversity had improved to levels last seen in the 1950s.[17]

However, industrial and agricultural runoff along with runoff from developed areas pose a continuing threat to marine ecosystems in the bay, particularly by clouding the water with sediments and algae blooms, and seagrass coverage declined slightly in the late 2010s.[15][18][1] Wastewater pollution from old phosphate plants near the shoreline has been a particular problem. For example, in 2004, a leak of 65 million gallons of acidic water from a Cargill phosphate plant on the bay's southern shore severely impacted wetlands in the vicinity of the spill.[19]

And in April 2021, a breach of a wastewater reservoir at the long-closed Piney Point phosphate plant sent over 200 millions gallons of nutrient-rich mine tailings streaming into lower Tampa Bay.[20] The resulting growth of red tide algae led to an ecocide and killed over 1000 tons of fish in the bay and along the nearby gulf coast and may lead to further damage to seagrass beds.[1]

Climate change

Tampa Bay, like other parts of Florida, is extremely vulnerable to sea level rise caused by climate change.[18] The sea level has risen 8 inches (200 mm) since 1946.[18] Tampa Bay is also one of the areas in the US most at risk when hurricanes arrive because of its location, growing population, and the geography of the bay.[21]

The Tampa Bay Regional Resiliency Coalition coordinates the region's response to climate change.[22] Communities throughout the Bay, including St. Petersburg and Tampa are adapting infrastructure and buildings to face changes in sea level.[18]

Human habitation

Early inhabitants

Humans have lived in Florida for millennia, at least 14,000 years. Due to worldwide glaciation, sea levels were much lower at the time, and Florida's peninsula extended almost 60 miles west of today's coastline. Paleo-Indian sites have been found near rivers and lakes in northern Florida, leading to speculation that these first Floridians also lived on Tampa Bay when it was still a freshwater lake.[23] Evidence of human habitation from this early period has been found at the Harney Flats site, which is approximately 10 miles east of the current location of Tampa's downtown waterfront.[24]

The earliest evidence of human habitation directly on the shores of Tampa Bay comes from the Manasota culture, a variant of the Weeden Island culture, who lived in the area beginning around 5,000–6,000 years ago, after sea levels had risen to near modern levels and the bay was connected to the Gulf of Mexico.[25] This culture, which relied almost exclusively on the bay for food and other resources, was in turn replaced by the similar Safety Harbor culture by approximately 800 AD. The pre-contact Indigenous nation most associated with the Tampa Bay are the historic Tocobaga nation,[26] who are known to be among the ancestors of the contemporary Seminole and Miccosukee Tribes of Florida. [27]

European exploration

The Safety Harbor culture was dominant in the area at the time of first contact with Europeans in the mid-1500s. The Tocobaga, who built their principal town near today's Safety Harbor in the northwest corner of Old Tampa Bay, are the most documented group from that era because they had the most interactions with Spanish explorers. However, there were many other coastal villages organized into various small chiefdoms all around the bay.[28]

Not finding gold or silver in the vicinity and unable to convert the native inhabitants to Christianity, the Spanish did not remain in the Tampa Bay area for long. However, diseases they introduced decimated the native population over the ensuing decades,[29] leading to the near-total collapse of every established culture across peninsular Florida. Between this depopulation and the indifference of its colonial owners, the Tampa Bay region would be virtually uninhabited for almost 200 years.

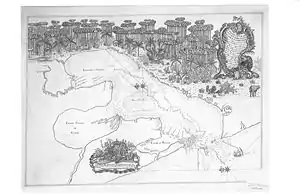

Tampa Bay was given different names by early mapmakers. Spanish maps dated from 1584 identifies Tampa Bay as Baya de Spirito Santo ("Bay of the Holy Spirit").[30] A map dated 1695 identifies the area as Bahia Tampa.[31] Later maps dated 1794[32] and 1800[33] show the bay divided with three different names, Tampa Bay west of the Interbay peninsula and Hillsboro Bay on the east with an overall name of Bay of Spiritu Santo. At other times, the entire bay was identified as The Bay of Tocobaga.[34]

United States control

The United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821. The name Spirito Santo seems to have disappeared from maps of the region in favor of "Tampa Bay" (sometimes divided into Tampa and Hillsboro Bays) soon after the US established Fort Brooke at the mouth of the Hillsborough River in 1824.[35] For the next several decades, during the Seminole Wars, the Tampa Bay would be a primary point of confrontation, detention, and forced expulsion of the Seminole & Miccosukee people of Florida. Fort Brooke,[36] Fort Dade, and the American military's miscellaneous Egmont Key facilities [37][38] were the primary sites associated with the removal of the Seminole in the Floridian leg of the Trail of Tears.[39][40]

For the next 100 years, many new communities were founded around the bay. Fort Brooke begat Tampa on the northeast shore, Fort Harrison (a minor military outpost on Florida's west coast) begat Clearwater, the trading post of "Braden's Town" developed into Bradenton on the south, and St. Petersburg grew quickly after its founding in the late 19th century, on the western bay shore opposite Tampa. By 2010, the Tampa Bay Area was home to over 4 million residents.

By sea

As Tampa began to grow in the mid-1800s, roads across central Florida were still just rough trails and rail lines did not yet extend down the Florida peninsula, so the most convenient means of traveling to and from the area was by sea. By the late 19th century, however, the shallow nature of Tampa Bay made it impossible for large modern vessels with deeper drafts to reach the city of Tampa's downtown wharves on Hillsboro Bay. Most ships would anchor well out from shore and transfer cargo and passengers to and from the city in smaller boats.[12]

Henry B. Plant's railroad line reached the area in 1884 and ran across the Interbay Peninsula to Old Tampa Bay, where he built the town and shipping facility of Port Tampa at its terminus.[41] In 1898, Plant used his connections in the federal government to make Port Tampa a major embarkation point for the U.S. Army during the Spanish–American War, leading to the U.S. Congress appropriating funds for the United States Army Corps of Engineers to begin the first large dredging operation in Tampa Bay. A deep shipping channel was created which linked Port Tampa to the mouth of the bay, enabling Plant to greatly expand his steamship line.[42][43] In 1917, the Corps of Engineers dredged another channel from the mouth of Tampa Bay to the Port of Tampa, instantly making the city an important shipping center.

The Corps of Engineers currently maintains more than 80 miles of deep-water channels in Tampa Bay up to a depth of 47 feet. These must be continuously re-dredged and deepened due to the sandy nature of the bay bottom. While dredging has enabled seaborne commerce to become an important part of the Tampa Bay area's economy, it has also damaged the bay's water quality and ecology. More care has been taken in recent decades to lessen the environmental impact of dredging.[44] Dredged material has also been used to create several spoil islands on the eastern side of Hillsboro Bay. These islands have become important nesting sites for many seabirds, including threatened species such as oystercatchers, and have been designated as "sanctuary islands" that are off-limits to boaters.[45][46]

Tampa's waterfront, 1890.

Tampa's waterfront, 1890..jpg.webp) Port Tampa, c. 1900.

Port Tampa, c. 1900.

Ports on Tampa Bay

- Port Tampa Bay (known as the Port of Tampa until 2014): Oldest port on Tampa Bay, can trace its roots to the wharves of Fort Brooke in the 1820s. Currently centered east and southeast of downtown Tampa on Hillsboro and McKay Bays. Largest port in Florida; 10th largest in the nation. Port Tampa Bay accommodates half of Florida's cargo in the form of bulk, roll-on/roll-off, refrigerated and container cargo, and petroleum products.[47] Home to extensive ship repair and building industry and several cruise ship terminals.[48]

- Port Tampa: Established in 1885 by Henry B. Plant at the terminus of the Plant System railroad line on the eastern shore of Old Tampa Bay. Eclipsed in tonnage and importance by the Port of Tampa in the early 1900s, but still an important arrival point for aviation fuel which is piped to nearby Tampa International Airport and MacDill Air Force Base.

- Port Manatee: Located on the southern shore of Lower Tampa Bay. Most refrigerated dockside space of any Gulf of Mexico port. Ranked fifth among Florida's fourteen seaports in total annual cargo tonnage.[49]

- The Port of St. Petersburg: Located on the St. Petersburg waterfront on Old Tampa Bay and operated by the city. Smallest of Florida's ports, caters mainly to private vessels. Site of U.S. Coast Guard station.[50]

By land

In the early 20th century, traveling overland between the growing communities around Tampa Bay was an arduous process. The trip between Tampa and St. Petersburg was almost 50 miles (80 km) around the north end of Old Tampa Bay and took up to 12 hours by train and over a full day over uncertain roads by car.[51][52] The trip between St. Petersburg and Bradenton was even longer – over 70 miles (110 km) all the way around Tampa Bay, a trip that still took about two hours into the 1950s.[53]

In 1924, the Gandy Bridge over Old Tampa Bay reduced the driving distance between Tampa and St. Petersburg to 19 miles (31 km).[54] Ten years later, the Davis Causeway (later renamed the Courtney Campbell Causeway) was built between Clearwater and Tampa. More bridges criss-crossed Tampa Bay over the ensuing decades, making travel between the surrounding communities much faster and furthering the economic development of the Tampa Bay area.

Bridges that cross Tampa Bay

- Sunshine Skyway Bridge: Opened 1954. Spans Lower Tampa Bay from Bradenton on the south to St. Petersburg on the north, greatly reducing travel times between Manatee and Pinellas Counties. Part of I-275 & US 19.

- Gandy Bridge: Opened 1924 (first roadway bridge over Tampa Bay). Spans Old Tampa Bay from Tampa on the east to St. Petersburg on the west. Part of U.S. Route 92.

- Howard Frankland Bridge: Opened 1960. Spans middle of Old Tampa Bay from Tampa on the east to St. Pete on the west. Part of I-275.

- Courtney Campbell Causeway: Opened 1934. Spans northern Old Tampa Bay from Tampa on the east to Clearwater on the west. Part of Florida State Road 60.

- Bayside Bridge: Opened 1993. Runs roughly parallel to the western shore of Old Tampa Bay from Largo / St. Petersburg on the south to Clearwater on the north. Built to help relieve traffic congestion on nearby US-19.

- 22nd Street Causeway: Opened 1926. Bridge portion spans the mouth of McKay Bay near Port Tampa Bay. Part of U.S. Route 41.

By air

The difficulty of traveling between Tampa and St. Petersburg in the early 20th century inspired the world's first scheduled air service, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line, which operated during the tourist season of 1914.[51][52]

While the construction of bridges made air travel across Tampa Bay unnecessary, several airports have been built along the shoreline. Albert Whitted Airport on the St. Petersburg waterfront and Peter O. Knight Airport on Davis Island near downtown Tampa were both established in the 1930s. Later, Tampa International Airport and St. Pete–Clearwater International Airport were established on opposite sides of Old Tampa Bay, and MacDill Air Force Base opened on the southern tip of Tampa's Interbay Peninsula.

References

- Sampson, Zachary; Weber, Natalie (July 23, 2021). "Red Tide's return raises fears about the health of Tampa Bay". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- Craig Pittman (July 7, 2008). "Media found the Rays, lost the 'Bay'". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- Guzzo, Paul (November 16, 2022). "Tampa Bay is not the name of a city, locals say. History proves it was". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved November 16, 2022.

- Kunneke, J.T., and T.F. Palik, 1984. "Tampa Bay environmental atlas", U.S. Fish Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rep. 85(15) Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, page 3. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- Edgar, N. T.; Willard, D. A.; Brooks, G. R.; Cronin, T. D.; Hastings, D. W.; Flower, B. P.; Swarzenski, P. W.; Hollander, D. J.; Larson, R.; Hine, A. C.; Suthard, B. C.; Locker, S. D.; Greenwood, W. J. (2002). "Holocene and Pleistocene Marine and Non-marine Sediment from Tampa Bay, Florida". Harvard.edu. 2002. Bibcode:2002AGUFMOS61A0191E.

- St. Petersburg Times Depths detail bay's beginnings Archived 2011-12-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "GulfBase - Tampa Bay and Keys". gulfbase.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Map of the Tampa Bay Watershed". 22 March 2009. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009.

- "Tampa Bay Estuary Program" Archived 2007-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, Official Website

- "Can manatees survive without warm waters from power plants?", Tampa Tribune (tbo.com), Jan. 8, 2011.

- "Dredging and Dredged Material Management" Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Tampa Bay Estuary Program

- "Some Historical Accounts of the Natural Conditions in Tampa Bay and Hillsborough County" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- "Tampa Bay". epa.gov. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Seagrass Meadows of Tampa Bay - A Review" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- Carter, Cathy (May 17, 2021). "Seagrass In Tampa Bay Declined 13 Percent In Recent Years". WUSF Public Media. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- "Ten Communities: Profiles in Environmental Progress". nara.gov. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Tampa Bay sea grasses, a leading indicator of water health, hit 60-year high" Archived 2011-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, St. Petersburg Times

- Fortado, Lindsay (September 20, 2019). "Tampa Bay cities prepare for rising sea levels and storm risk". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- Salinero, Mike (September 2, 2012). "Mosaic Co. environmental project to revive ecological disaster area". The Tampa Tribune. Tampa Bay, Florida. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Callihan, Ryan (April 4, 2021). "A worst case at Piney Point? 20-foot (6.1 m) wall of water. DeSantis tours site, stresses safety". Miami Herald. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Resnick, Brian (2019-09-11). "26 feet of water: What the worst-case hurricane scenario looks like for Tampa Bay". Vox. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- Wilson, Kirby (February 22, 2019). "Climate change is here. Will Tampa Bay finally get ready?". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- "Florida's Indians". ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Florida anthropologist". ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Manasota". Co.pinellas.fl.us. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida. "Tocobaga Indians of Tampa Bay". Exploring Florida. University of South Florida. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- SemTribe. "The Ancestors". Seminole Tribe of Florida. Seminole Tribe. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- "Tocobaga Indians of Tampa Bay". Fcit.usf.edu. Archived from the original on 2010-04-06. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8

- "University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Books and Manuscript Library: 1584 map of La Florida". Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- "University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Books and Manuscript Library: 1695 Spanish Map". Archived from the original on June 24, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- "Historical Map Archive: The Peninsula and Gulf of Florida, or New Bahama Channel, with the Bahama Islands". Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- "University of Georgia Libraries, Hargrett Rare Books and Manuscript Library: An exact map of North and South Carolina & Georgia, with East and West Florida". Archived from the original on June 1, 2010. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Swanton, John R. (April 1952). "De Soto's First Headquarters in Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 30 (4): 311. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- "Historical Map Archive: 1933 Map of Florida by A. Finley, Philadelphia". Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- Morrow, Emerald. "'We're not extinct': Seminole Tribe of Florida highlights Tampa history for Indigenous People's Day". Channel 10 News, Tampa Bay. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Guzzo, Paul. "Seminole Tribe searches for remains of ancestors on Egmont Key". The Tampa Bay Times. The Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Guzzo, Paul. "They can't turn back waves, but USF and Seminoles are preserving Egmont Key in digital form". The Tampa Bay Times. The Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Simpson, Linda. "Seminole Trails of Tears". Seminole Nation, Indian Territory. Seminole Nation, Indian Territory. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- O'Brian, Bill. "National Wildlife Refuges Along the Trail of Tears". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- "Henry Plant's Southern Empire". plantmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Corps, Port Consider Channel Widening Options". Baysoundings.com. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "The Spanish–American War". plantmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Dredging and Dredged: Material Management" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- "Sanctuary Islands". audubon.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Hammett, Yvette (12 April 2015). "Port Tampa Bay has to dredge with care in nesting season". Tampa Tribune. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Port of Tampa will fuel region with new $56 million petroleum terminal". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "About the Tampa Port Authority". Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "Port Facts". portmanatee.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Port St. Pete - St. Petersburg". www.stpete.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-01.

- "The World's First Scheduled Airline". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Provenzo. Jr. , Eugene F. (July 1979). "The St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 58 (1): 72–77. JSTOR 3014618.

- Blizin, Jerry (20 October 2009). "Spectacular Sunshine Skyway replaced ferryboats in 1954". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- George Gandy Sr. Made $1,932,000 Span Possible St. Petersburg Times, April 18, 1956