National Rally

The National Rally (French: Rassemblement National, pronounced [ʁasɑ̃bləmɑ̃ nɑsjɔnal]; RN), until 2018 known as the National Front (French: Front National, pronounced [fʁɔ̃ nɑsjɔnal]; FN), is a far-right[9][10][11][12][13] political party in France. It is the largest parliamentary opposition group in the National Assembly and the party has seen its candidate reach the second round in the 2002, 2017 and 2022 presidential elections. It is an anti-immigration party, advocating significant cuts to legal immigration and protection of French identity,[14] as well as stricter control of illegal immigration. It also advocates for a 'more balanced' and 'independent' French foreign policy by opposing French military intervention in Africa and by distancing France from the American sphere of influence by leaving NATO's integrated command. It supports reform of the European Union (EU) and its related organisations. It also supports economic interventionism and protectionism, and zero tolerance of breaches of law and order.[15] The party has been accused of promoting xenophobia and antisemitism.[13]

National Rally Rassemblement National | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | RN |

| President | Jordan Bardella |

| Vice Presidents | |

| Parliamentary party leader | Marine Le Pen (National Assembly) |

| Founder | Jean-Marie Le Pen[1] |

| Founded | 5 October 1972 |

| Headquarters | 114 bis rue Michel-Ange 75016 Paris |

| Youth wing | Rassemblement national de la jeunesse |

| Security wing | Department for Protection and Security |

| Membership (2023) | 45,000[2] |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right[A] |

| National affiliation | Rassemblement bleu Marine (2012–2017) |

| European affiliation | Identity and Democracy Party |

| European Parliament group | Identity and Democracy[nb 1] |

| Colours | Navy blue[nb 2] |

| National Assembly | 87 / 577 |

| Senate | 3 / 348 |

| European Parliament | 19 / 79 |

| Presidencies of Regional Councils | 0 / 17 |

| Regional Councillors | 252 / 1,758 |

| Presidencies of Departmental Councils | 0 / 101 |

| Departmental Councillors | 26 / 4,108 |

| Website | |

| rassemblementnational | |

^ A: The RN is considered part of the radical right, a subset of the far-right that does not oppose democracy.[6][7][8] | |

The party was founded in 1972 to unify the French nationalist movement. Its political views are nationalist, nativist and anti-globalist. Jean-Marie Le Pen founded the party and was its leader until his resignation in 2011. While the party struggled as a marginal force for its first ten years, it has been a major force of French nationalism since 1984.[16] It has put forward a candidate at every presidential election but one since 1974. In 2002, Jean-Marie came second in the first round, but finished a distant second in the runoff to Jacques Chirac.[17] His daughter Marine Le Pen was elected to succeed him as party leader in 2012. She temporarily stepped down in 2017 in order to concentrate on her presidential candidacy; she resumed her presidency after the election.[18] She headed the party until 2021, when she temporarily resigned again. A year later, Jordan Bardella was elected as her successor.[19]

The party has seen an increase in its popularity and acceptance in French society in recent years. While her father was nicknamed the "Devil of the Republic" by mainstream media and sparked outrage for hate speech, including Holocaust denial and Islamophobia, Marine Le Pen pursued a policy of "de-demonisation" of the party by softening its image and trying to frame the party as being neither right nor left.[20] She endeavoured to extract it from its far-right roots, as well as censuring controversial members like her father, who was suspended and then expelled from the party in 2015.[21] Following her election as the leader of the party in 2011, the popularity of the FN grew.[22] By 2015, the FN had established itself as a major political party in France.[23][24]

At the FN congress of 2018, Marine Le Pen proposed renaming the party Rassemblement national (National Rally),[25] and this was confirmed by a ballot of party members.[26] Formerly strongly Eurosceptic, the National Rally changed policies in 2019, deciding to campaign for a reform of the EU rather than leaving it and to keep the euro as the main currency of France (together with the CFP franc for some collectivities).[27] In 2021, Le Pen announced that she wanted to remain in the Schengen Area, citing "an attachment to the European spirit", but to reserve free movement to nationals of a European Economic Area country, excluding residents and visitors of another Schengen country.[28][29]

Le Pen reached the second round of the 2017 presidential election, receiving 33.9% of the votes in the run-off and losing to Emmanuel Macron. Again in the 2022 election, she faced Macron in the run-off, receiving 41.45% of the votes. In the 2022 parliamentary elections, the National Rally, increased the number of its MPs in the National Assembly from 7 to 89 seats.

Background

The party's ideological roots can be traced to both Poujadism, a populist, small business tax protest movement founded in 1953 by Pierre Poujade and right-wing dismay over the decision by French President Charles de Gaulle to abandon his promise of holding on to the colony of French Algeria, (many frontistes, including Le Pen, were part of an inner circle of returned servicemen known as Le cercle national des combattants).[30][31] During the 1965 presidential election, Le Pen unsuccessfully attempted to consolidate the right-wing vote around the right-wing presidential candidate Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour.[32] Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, the French far-right consisted mainly of small extreme movements such as Occident, Groupe Union Défense (GUD), and the Ordre Nouveau (ON).[33]

Espousing France's Catholic and monarchist traditions, one of the primary progenitors of the party was the Action Française, founded at the end of the 19th century, and its descendants in the Restauration Nationale, a pro-monarchy group that supports the claim of the Count of Paris to the French throne.[34][35]

History

Foundation (1972–1973)

While the ON had competed in some local elections since 1970, at its second congress in June 1972 it decided to establish a new political party to contest the 1973 legislative elections.[36][37] The party was launched on 5 October 1972 under the name National Front for French Unity (Front national pour l'unité française), or Front National.[38] In order to create a broad movement, the ON sought to model the new party (as it earlier had sought to model itself) on the more established Italian Social Movement (MSI), which at the time appeared to establish a broad coalition for the Italian right. The FN adopted a French version of the MSI tricolour flame as its logo.[39][40][41] It wanted to unite the various French far-right currents, and brought together "nationals" of Le Pen's group and Roger Holeindre's Party of French Unity; "nationalists" from Pierre Bousquet's Militant movement or François Brigneau's and Alain Robert's Ordre Nouveau; the anti-Gaullist Georges Bidault's Justice and Liberty movement; as well as former Poujadists, Algerian War veterans, and some monarchists, among others.[38][42][43] Le Pen was chosen to be the first president of the party, as he was untainted with the militant public image of the ON and was a relatively moderate figure on the far-right.[44][45]

The National Front fared poorly in the 1973 legislative elections, receiving 0.5% of the national vote (although Le Pen won 5% in his Paris constituency).[46] In 1973 the party created a youth movement, the Front national de la jeunesse (National Front of the Youth, FNJ). The rhetoric used in the campaign stressed old far-right themes and was largely uninspiring to the electorate at the time.[47] Otherwise, its official program at this point was relatively moderate, differing little from the mainstream right.[48] Le Pen sought the "total fusion" of the currents in the party, and warned against crude activism.[49] The FNJ were banned from the party later that year.[50][47] The move towards the mainstream cost it many leading members and much of its militant base.[50]

In the 1974 presidential election, Le Pen failed to find a mobilising theme for his campaign.[51] Many of its major issues, such as anti-communism, were shared by most of the mainstream right.[52] Other FN issues included calls for increased French birth rates, immigration reduction (although this was downplayed), establishment of a professional army, abrogation of the Évian Accords, and generally the creation of a "French and European renaissance."[53] Despite being the only nationalist candidate, he failed to gain the support of a united far-right, as the various groups either rallied behind other candidates or called for voter abstention.[54] The campaign further lost ground when the Revolutionary Communist League published a denunciation of Le Pen's alleged involvement in torture during his time in Algeria.[54] In his first presidential election, Le Pen gained only 0.8% of the national vote.[54]

FN–PFN rivalry (1973–1981)

Following the 1974 election, the FN was obscured by the appearance of the Party of New Forces (PFN), founded by FN dissidents (largely from the ON).[55][56] Their competition weakened both parties throughout the 1970s.[55] Along with the growing influence of François Duprat and his "revolutionary nationalists", the FN gained several new groups of supporters in the late 1970s and early 1980s: Jean-Pierre Stirbois (1977) and his "solidarists", Bruno Gollnisch (1983), Bernard Antony (1984) and his Catholic fundamentalists, as well as Jean-Yves Le Gallou (1985) and the Nouvelle Droite.[57][58] Following the death of Duprat in a bomb attack in 1978, the revolutionary nationalists left the party, while Stirbois became Le Pen's deputy as his solidarists effectively ousted the neo-fascist tendency in the party leadership.[59] A radical group split off in 1980 and founded the French Nationalist Party, dismissing the FN as becoming too Zionist and Le Pen as the "puppet" of the Jews.[60] The far right was marginalised altogether in the 1978 legislative elections, although the PFN was better off.[61][62] For the first election for the European Parliament in 1979, the PFN had become part of an attempt to build a "Euro-Right" alliance of European far-right parties, and was in the end the only one of the two that contested the election.[63] It fielded Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour as its primary candidate, while Le Pen called for voter abstention.[64]

For the 1981 presidential election, both Le Pen and Pascal Gauchon of the PFN declared their intentions to run.[64] However, an increased requirement regarding obtaining signatures of support from elected officials had been introduced for the election, which left both Le Pen and Gauchon unable to stand for the election. In France, parties have to secure support from a specific number of elected officials, from a specific number of departments, in order to be eligible to run for election. In 1976, the number of required elected officials was increased fivefold from the 1974 presidential cycle, and the number of departments threefold.[64] The election was won by François Mitterrand of the Socialist Party (PS), which gave the political left national power for the first time in the Fifth Republic; he then dissolved the National Assembly and called a snap legislative election.[65] The PS attained its best ever result with an absolute majority in the 1981 legislative election.[66] This "socialist takeover" led to a radicalisation in centre-right, anti-communist, and anti-socialist voters.[67] With only three weeks to prepare its campaign, the FN fielded only a limited number of candidates and won only 0.2% of the national vote.[52] The PFN was even worse off, and the election marked the effective end of competition from the party.[52]

Electoral breakthrough (1982–1988)

While the French party system had been dominated by polarisation and competition between the clear-cut ideological alternatives of two political blocs in the 1970s, the two blocs had largely moved towards the centre by the mid-1980s. This led many voters to perceive the blocs as more or less indistinguishable, particularly after the Socialists' "austerity turn" (tournant de la rigueur) of 1983,[68] in turn inducing them to seek out to new political alternatives.[69] By October 1982, Le Pen supported the prospect of deals with the mainstream right, provided that the FN did not have to soften its position on key issues.[70] In the 1983 municipal elections, the centre-right Rally for the Republic (RPR) and centrist Union for French Democracy (UDF) formed alliances with the FN in a number of towns.[70] The most notable result came in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, where Le Pen was elected to the local council with 11% of the vote.[70][71] Later by-elections kept media attention on the party, and it was for the first time allowed to pose as a viable component of the broader right.[72][73] In a by-election in Dreux in October, the FN won 17% of the vote.[70] With the choice of defeat to the political left or dealing with the FN, the local RPR and UDF agreed to form an alliance with the FN, creating national sensation, and together won the second round with 55% of the vote.[70][71] The events in Dreux were a monumental factor for the rise of the FN.[74]

Le Pen protested the media boycott against his party by sending letters to President Mitterrand in mid-1982.[72] After some exchanges of letters, Mitterrand instructed the heads of the main television channels to give equitable coverage to the FN.[72] In January 1984, the party made its first appearance in a monthly poll of political popularity, in which 9% of respondents held a "positive opinion" of the FN and some support for Le Pen.[72] The next month, Le Pen was for the first time invited onto a prime-time television interview programme, which he himself later deemed "the hour that changed everything".[72][75] The 1984 European elections in June came as a shock, as the FN won 11% of the vote and ten seats.[76] Notably, the election used proportional representation and was considered to have a low level of importance by the public, which played to the party's advantage.[77] The FN made inroads in both right-wing and left-wing constituencies, and finished second in a number of towns.[78] While many Socialists had arguably exploited the party in order to divide the right,[79] Mitterrand later conceded that he had underestimated Le Pen.[72] By July, 17% of opinion poll respondents held a positive opinion of the FN.[80]

By the early 1980s, the FN featured a mosaic of ideological tendencies and attracted figures who were previously resistant to the party.[80] The party managed to draw supporters from the mainstream right, including some high-profile defectors from the RPR, UDF, and the National Centre of Independents and Peasants (CNIP).[80] In the 1984 European elections, eleven of the 81 FN candidates came from these parties, and the party's list also included an Arab and a Jew (although in unwinnable positions).[80] Former collaborators were also accepted in the party, as Le Pen urged the need for "reconciliation", arguing that forty years after the war the only important question was whether or not "they wish to serve their country".[80] The FN won 8.7% overall support in the 1985 cantonal elections, and over 30% in some areas.[81]

For the 1986 legislative elections, the FN took advantage of a new proportional representation system that had been imposed by Mitterrand in order to moderate a foreseeable defeat for his PS.[81][82] In the election, the FN won 9.8% of the vote and 35 seats in the National Assembly.[81] Many of its seats could be filled by a new wave of respectable political operatives, notables, who had joined the party after its 1984 success.[83][84] The RPR won a majority with smaller centre-right parties, and thus avoided the need to deal with the FN.[81] Although it was unable to exercise any real political influence, the party could project an image of political legitimacy.[84][85] Several of its legislative proposals were extremely controversial and had a socially reactionary and xenophobic character, among them attempts to restore the death penalty, expel foreigners who "proportionally committed more crimes than the French", restrict naturalisation, introduce a "national preference" for employment, impose taxes on the hiring of foreigners by French companies, and privatise Agence France-Presse.[86] The party's time in the National Assembly effectively came to an end when Jacques Chirac reinstated the two-round system of majority voting for the next election.[87] In the regional elections held on the same day, it won 137 seats, and gained representation in 21 of the 22 French regional councils.[81] The RPR depended on FN support to win presidencies in some regional councils, and the FN won vice-presidential posts in four regions.[81]

Consolidation (1988–1997)

Le Pen's campaign for the upcoming presidential election unofficially began in the months following the 1986 election.[88] To promote his statesmanship credentials, he made trips to South East Asia, the United States, and Africa.[88] The management of the formal campaign, launched in April 1987, was entrusted to Bruno Mégret, one of the new notables.[88] With his entourage, Le Pen traversed France for the entire period and, helped by Mégret, employed an American-style campaign.[89] Le Pen's presidential campaign was highly successful; no candidates came close to rival his ability to excite audiences at rallies and boost ratings at television appearances.[88] Using a populist tone, Le Pen presented himself as the representative of the people against the "gang of four" (RPR, UDF, PS, Communist Party), while the central theme of his campaign was "national preference".[88] In the 1988 presidential election, Le Pen won an unprecedented 14.4% of the vote,[90] and double the votes from 1984.[91]

The FN was hurt in the snap 1988 legislative elections by the return two-ballot majority voting, by the limited campaign period, and by the departure of many notables.[85][92] In the election the party retained its 9.8% support from the previous legislative election, but was reduced to a single seat in the National Assembly.[92] Following some anti-Semitic comments made by Le Pen and the FN newspaper National Hebdo in the late 1980s, some valuable FN politicians left the party.[93][94] Other quarrels soon also left the party without its remaining member of the National Assembly.[95] In November 1988, general secretary Jean-Pierre Stirbois, who, together with his wife Marie-France, had been instrumental in the FN's early electoral successes, died in a car accident, leaving Bruno Mégret as the unrivalled de facto FN deputy leader.[88][95] The FN only got 5% in the 1988 cantonal elections, while the RPR announced it would reject any alliance with the FN, now including at local level.[96] In the 1989 European elections, the FN held on to its ten seats as it won 11.7% of the vote.[97]

In the wake of FN electoral success, the immigration debate, growing concerns over Islamic fundamentalism, and the fatwa against Salman Rushdie by Ayatollah Khomeini, the 1989 affaire du foulard was the first major test of the relations between the values of the French Republic and Islam.[98] Following the event, surveys found that French public opinion was largely negative towards Islam.[99] In a 1989 legislative by-election in Dreux, FN candidate Marie-France Stirbois, campaigning on an anti-Islamism platform, returned a symbolic FN presence to the National Assembly.[100] By the early 1990s, some mainstream politicians began employing anti-immigration rhetoric.[101] In the first round of the 1993 legislative elections the FN soared to 12.7% of the overall vote, but did not win a single seat due to the nature of the electoral system (if the election had used proportional representation, it would have won 64 seats).[102][103] In the 1995 presidential election, Le Pen rose slightly to 15% of the vote.[104]

The FN won an absolute majority (and thus the mayorship) in three cities in the 1995 municipal elections: Toulon, Marignane, and Orange.[105] (It had won a mayorship only once before, in the small town of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard in 1989.)[106] Le Pen then declared that his party would implement its "national preference" policy, with the risk of provoking the central government and being at odds with the laws of the Republic.[106] The FN pursued interventionist policies with regards to the new cultural complexion of their towns by directly influencing artistic events, cinema schedules, and library holdings, as well as cutting or halting subsidies for multicultural associations.[107] The party won Vitrolles, its fourth town, in a 1997 by-election, where similar policies were pursued.[108] Vitrolles' new mayor Catherine Mégret (who ran in place of her husband Bruno)[109] went further in one significant measure, introducing a special 5,000-franc allowance for babies born to at least one parent of French (or EU) nationality.[108] The measure was ruled illegal by a court, also giving her a suspended prison sentence, a fine, and a two-year ban from public office.[108]

Turmoil and split of the MNR (1997–2002)

In the 1997 legislative elections, the FN polled its best-ever result with 15.3% support in metropolitan France.[110][111] The result also showed that the party had become established enough to compete without its leader, who had decided not to run in order to focus on the 2002 presidential election.[112] Although it won only one seat in the National Assembly (Toulon),[113] it advanced to the second round in 132 constituencies.[114] The FN was arguably more influential now than it had been in 1986 with its 35 seats.[115] While Bruno Mégret and Bruno Gollnisch, favoured tactical cooperation with a weakened centre-right following the left's victory, Le Pen rejected any such compromise.[116] In the tenth FN national congress in 1997, Mégret stepped up his position in the party as its rising star and a potential leader following Le Pen.[117] Le Pen however refused to designate Mégret as his successor-elect, and instead made his wife Jany the leader of the FN list for the upcoming European election.[118]

Mégret and his faction left the FN in January 1999 and founded the National Republican Movement (MNR), effectively splitting the FN in half at most levels.[119][120] Many of those who joined the new MNR had joined the FN in the mid-1980s, in part from the Nouvelle Droite, with a vision of building bridges to the parliamentary right.[119] Many had also been particularly influential in intellectualising the FN's policies on immigration, identity and "national preference", and, following the split, Le Pen denounced them as "extremist" and "racist".[119] Support for the parties was almost equal in the 1999 European election, as the FN polled its lowest national score since 1984 with just 5.7%, and the MNR won 3.3%.[121] The effects of the split, and competition from more moderate nationalists, had left their combined support lower than the FN result in 1984.[122]

Presidential run-off (2002)

For the 2002 presidential election, opinion polls had predicted a run-off between incumbent President Chirac and PS candidate Lionel Jospin.[123][124] The shock was thus great when Le Pen unexpectedly outperformed Jospin (by 0.7%) in the first round, placing second and advancing to the runoff.[124] This resulted in the first presidential run-off since 1969 without a leftist candidate and the first ever with a candidate of the far-right.[125] To Le Pen's advantage, the election campaign had increasingly focused on law and order issues, helped by media attention on a number of violent incidents.[126] Jospin had also been weakened due to the competition between an exceptional number of leftist parties.[127] Nevertheless, Chirac did not even have to campaign in the second round, as widespread anti-Le Pen protests from the media and public opinion culminated on May Day, with an estimated 1.5 million demonstrators across France.[128] Chirac also refused to debate with Le Pen, and the traditional televised debate was cancelled.[129] In the end, Chirac won the presidential run-off with an unprecedented 82.2% of the vote and with 71% of his votes—according to polls—cast simply "to block Le Pen".[129] Following the presidential election, the main centre-right parties merged to form the broad-based Union for a Popular Movement (UMP).[130] The FN failed to hold on to Le Pen's support for the 2002 legislative elections, in which it got 11.3% of the vote.[131] It nevertheless outpolled Mégret's MNR, which won a mere 1.1% support, even though it had fielded the same number of candidates.[132]

Decline (2003-2010)

A new electoral system of two-round voting had been introduced for the 2004 regional elections, in part in an attempt to reduce the FN's influence in regional councils.[133] The FN won 15.1% of the vote in metropolitan France, almost the same as in 1998, but its number of councillors was almost halved due to the new electoral system.[134] For the 2004 European elections, too, a new system less favourable to the FN had been introduced.[135] The party regained some of its strength from 1999, earning 9.8% of the vote and seven seats.[135]

For the 2007 presidential election, Le Pen and Mégret agreed to join forces. Le Pen came fourth in the election with 11% of the vote, and the party won no seats in the legislative election of the same year. The party's 4.3% support was the lowest score since the 1981 election and only one candidate, Marine Le Pen in Pas de Calais, reached the runoff (where she was defeated by the Socialist incumbent). These electoral defeats partly accounted for the party's financial problems. Le Pen announced the sale of the FN headquarters in Saint-Cloud, Le Paquebot, and of his personal armoured car.[136] Twenty permanent employees of the FN were also dismissed in 2008.[137] In the 2010 regional elections the FN appeared to have re-emerged on the political scene after surprisingly winning almost 12% of the overall vote and 118 seats.[138]

Revival of the FN (2011–2012)

Jean-Marie Le Pen announced in September 2008 that he would retire as FN president in 2010.[123] Le Pen's daughter Marine Le Pen and FN executive vice-president Bruno Gollnisch campaigned for the presidency to succeed Le Pen,[123] with Marine's candidacy backed by her father.[123] On 15 January 2011, it was announced that Marine Le Pen had received the two-thirds vote needed to become the new leader of the FN.[139][140] She sought to transform the FN into a mainstream party by softening its xenophobic image.[123][139][140] Opinion polls showed the party's popularity increase under Marine Le Pen, and in the 2011 cantonal elections the party won 15% of the overall vote (up from 4.5% in 2008). However, due to the French electoral system, the party only won 2 of the 2,026 seats up for election.[141]

At the end of 2011, the National Front withdrew from the far-right Alliance of European National Movements and joined the more moderate European Alliance of Freedom. In October 2013, Bruno Gollnisch and Jean-Marie Le Pen resigned from their position in the AENM.

For the 2012 presidential election, opinion polls showed Marine Le Pen as a serious challenger, with a few polls even suggesting that she could win the first round of the election.[142][143] In the event, Le Pen came third in the first round, scoring 17.9% – the best showing ever in a presidential election for the FN at that time.

In the 2012 legislative election, the National Front won two seats: Gilbert Collard and Marion Maréchal.[144][145][146]

In two polls about presidential favourites in April and May 2013,[147] Marine le Pen polled ahead of president François Hollande but behind Nicolas Sarkozy.[147]

Electoral successes (2012–2017)

In the municipal elections held on 23 and 30 March 2014, lists officially supported by National Front won mayoralties in 12 cities: Beaucaire, Cogolin, Fréjus, Hayange, Hénin-Beaumont, Le Luc, Le Pontet, Mantes-la-Ville, the 7th arrondissement of Marseille, Villers-Cotterêts, Béziers and Camaret-sur-Aigues. While some of these cities were in southern France (like Fréjus) which traditionally votes more for right-wing parties than the rest of the country, others were located in northern France, where Socialist Party was strong until 2010s. Following the municipal elections, the National Front had, in cities of over 1,000 inhabitants, 1,546 and 459 councilors at two different levels of local government.[148] The international media described the results as "historic",[149][150][151] and "impressive", although the International Business Times suggested that "hopes for real political power remain a fantasy" for the National Front.[152]

The National Front received 4,712,461 votes in the 2014 European Parliament election, finishing first with 24.86% of the vote and 24 of France's 74 seats.[153] This was said to be "the first time the anti-immigrant, anti-EU party had won a nationwide election in its four-decade history."[154] The party's success came as a shock in France and the EU.[155][156]

Presidential and parliamentary election, rebranding (2017–2022)

On 24 April 2017, a day after the first round of the presidential election, Marine Le Pen announced that she would temporarily step down as the party's leader in an attempt to unite voters.[18] In the second round of voting, Le Pen was defeated 66.1% to 33.9% by her rival Emmanuel Macron of En Marche![157]

During the following parliamentary elections, the FN received 13.02% of the vote, which represented a disappointment compared to the 13.07% of the 2012 elections. The party appeared to have suffered from the demobilisation of its voters from the previous vote. However, 8 deputies were elected (6 FN and 2 affiliated), the best number for the FN in a parliamentary election using a majoritarian electoral system since its creation (proportional representation was used in the 1986 elections). Marine Le Pen was elected to the National Assembly for the first time, and Gilbert Collard was re-elected. Ludovic Pajot became the youngest member of the French parliament at 23.

In late 2017, Florian Philippot split from FN and formed The Patriots, due to the FN weakening its position on leaving the EU and abandoning the Euro.[158]

At the conclusion of the party congress in Lille on 11 March 2018, Marine Le Pen proposed renaming the party to Rassemblement national (National Rally) while keeping the flame as its logo. The new name was put to a vote of party members.[25] Rassemblement national had already been used as the name of a French party, the Rassemblement National Français, led by the radical right lawyer Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour. His presidential campaign in 1965 was managed by Jean-Marie Le Pen.[159] The name had also been used by the FN previously, for its parliamentary group between 1986 and 1988. However, the name change faced opposition from an already-existing party named "Rassemblement national", whose president, Igor Kurek, described it as "Gaullist and republican right": the party had previously registered its name with the National Institute of Industrial Property in 2013.[160][161] On 1 June, Le Pen announced that the name change was approved by party adherents with 80.81% in favour.[26]

During that party congress, Steve Bannon, former advisor to Donald Trump before and after his election, gave what has been described as a "populist pep talk".[162] Bannon advised the party members to "Let them call you racist, let them call you xenophobes, let them call you nativists. Wear it like a badge of honor. Because every day, we get stronger and they get weaker. ... History is on our side and will bring us victory." Bannon's remarks brought the members to their feet.[163][164][165]

In January 2019, ex-Sarkozy minister Thierry Mariani and former conservative lawmaker Jean-Paul Garraud, left Les Republicains (LR), joining the National Rally.[166]

During a 2021 debate Marine Le Pen was called "soft" on Islam by the Minister of the Interior in Macron's government, Gérald Darmanin.[167] Marine Le Pen has also called for a "national unity government" that would include people such as Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, former LR officials, and souverainistes on the left, such as former economy minister Arnaud Montebourg.[168]

In the months before the 2021 French regional elections political commentators noted an increased moderation in the party in order to attract conservative voters,[169] as well as a new image of the party as a force of "la Droite populaire" or the Social Right.[170][171] The party fared badly in these elections.[172]

In the 2022 French presidential election, Le Pen again reached the second round with 23.15% of the votes. Nonetheless she was ultimately defeated by incumbent Macron, receiving 41.45% of the votes in the run-off.[173]

In the 2022 French legislative election, the party received 18.68% of the votes in the first round[174] and won 89 seats in the National Assembly in the second round,[175] an increase on the previous total of 8 seats. Polling had indicated that the party would win only 15 to 45 seats. The 89 seats enabled National Rally to form a parliamentary group (for which 15 deputies are required) for the first time since 1986, when the national assembly was elected by proportional voting. The result made the party the third largest party in the assembly and the largest parliamentary opposition group.[176]

Jordan Bardella's leadership (from 2022)

Bardella was elected president of RN on 5 November 2022, ending Marine Le Pen's period as president of the party. Le Pen remained president of RN's parliamentary group[19]

Political profile

The party's ideology has been broadly described by scholars, including James Shields, Nonna Mayer, Jean-Yves Camus, Nicolas Lebourg and Michel Winock as nationalist, far-right (or Nouvelle droite) and populist.[177] Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg, following Pierre-André Taguieff's analysis, include the party in an old French tradition of "national populism" that can be traced back to Boulangism. National populists combine the social values of the left and the political values of the right, and advocate a referendary republic that would bypass traditional political divisions and institutions. Aiming at a unity of the political (the demos), ethnic (the ethnos) and social (the working class) interpretations of the "people", they claim to defend the "average Frenchman" and "common sense", against the "betrayal of inevitably corrupt elites".[178] The party has been also described as national conservative.[179][180]

The FN changed considerably since its foundation, as it pursued the principles of modernisation and pragmatism, adapting to the changing political climate.[181][182] Its message increasingly influenced mainstream political parties,[182][183] and some commentators described it as right-wing, moving closer towards the centre-right.[184][190] In the 2010s, the party attempted to "de-demonise" its image and changed its name to National Rally. A 2022 Kanar survey found that 46% of French voters saw Marine Le Pen as "representing a patriotic Right attached to traditional values", although 50% saw her as "a danger to democracy".[191]

Law and order

In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen campaigned on a law-and-order platform of zero tolerance, harsher sentencing, increased prison capacity, and a referendum on re-introducing the death penalty.[125] In its 2001 programme, the party linked the breakdown of law and order to immigration, deeming immigration a "mortal threat to civil peace in France."[127]

Marine Le Pen rescinded the party's traditional support for the death penalty with her 2017 campaign launch, instead announcing support for imprisonment "in perpetuity" for the "worst crimes" in February 2017.[192] In 2022, she proposed to hold a referendum on capital punishment in France if she were elected.[193][194]

The party opposed the 2016 criminalisation of the use of prostitution in France, on the grounds that it would negatively affect the safety of sex workers.[195]

Immigration

Since its early years, the party has called for immigration to be reduced.[196] The theme of exclusion of non-European immigrants was brought into the party in 1978 and became increasingly important in the 1980s.[197]

After the 1999 split, the FN cultivated a more moderate image on immigration and Islam, no longer calling for the systematic repatriation of legal immigrants but still supporting the deportation of illegal, criminal or unemployed immigrants.[198]

Following the Arab Spring (2011) rebellions in several countries, Marine Le Pen campaigned for a halt to the migration of Tunisian and Libyan immigrants to Europe.[199]

In November 2015, the party stated as its goal to have a net legal immigration rate (immigrants minus emigrants) of 10,000 in France per year. Since 2017, that yearly net immigration rate was around 182,000[200] if one takes into account only people born abroad from non-French parents, but was around 44,000 if one includes also the departures and returns of French expatriates.[201]

In 2022, Marine Le Pen proposed an end to “family reunification” rights for foreigners with residency permits and the end to the right to automatic citizenship for children born in France to foreigners living there.[191] She also supported a referendum on immigration policy.[193]

Islamism and Islamisation

Representatives of the party have connected immigration to Islamic terrorism.[202] In 2011, Marine Le Pen warned that wearing full face veils are "the tip of the iceberg" of Islamisation of French culture.[203] In 2021, the party proposed laws banning the hijab and the dissemination of Islamist ideologies.[204] In 2022, Le Pen stated that there was a difference between “fighting immigration and fighting immigrants” just as there was between respecting religious freedoms and tackling “religious totalitarianism”.[191]

Economy

At the end of the 1970s, Jean-Marie Le Pen broke away from the anti-capitalist heritage of Poujadism and espoused a market liberal and anti-statist programme which included lower taxes, reducing state intervention, reducing the size of the public sector, privatisation, and scaling back government bureaucracy. Some scholars have charaterised the FN's 1978 programme as "Reaganite before Reagan".[197]

The party's economic policy shifted from the 1980s to the 1990s from neoliberalism to protectionism.[205][206] This occurred within the framework of a changed international environment, from a battle between the Free World and Communism, to one between nationalism and globalisation.[115] During the 1980s, Jean-Marie Le Pen complained about the rising number of "social parasites", and called for deregulation, tax cuts, and the phasing-out of the welfare state.[206] As the party gained growing support from the economically vulnerable, it converted towards politics of social welfare and economic protectionism.[206] This was part of its shift away from its former claim of being the "social, popular and national right" to its claim of being "neither right nor left – French!"[207] Increasingly, the party's program became an amalgam of free market and welfarist policies. By the 2010s, some political commentators described its economic policies as left-wing.[115][208][209]

Under Marine Le Pen, the RN has supported economic nationalism,[210] which it calls "economic patriotism" and has advocated populist policies such as tax cuts for those under 30 and cuts in VAT on energy and essential products. The party has supported public services, protectionism and economic intervention, and opposed the increase in the fuel tax in 2018 and the increase in the retirement age in 2023.[191][211][212]

Feminism

In the 2002 legislative elections, the first under the new gender parity provision in the French Constitution, Le Pen's National Front was among the few parties to come close to meeting the law, with 49% female candidates; Jospin's Socialists had 36%, and Chirac's UMP had 19.6%.[213] Women voters in France were traditionally more attracted to mainstream conservative parties than the radical right until the 2000s. The proportion of women in the party has risen to 39% by 2017.[214]

Foreign policy

From the 1980s to the 1990s, the party's policy shifted from favouring the European Union to turning against it.[206] In 2002, Jean-Marie Le Pen campaigned on pulling France out of the EU and re-introducing the franc as the country's national currency.[125] In the early 2000s the party denounced the Schengen, Maastricht, and Amsterdam treaties as foundations for "a supranational entity spelling the end of France."[215] In 2004, the party criticised the EU as "the last stage on the road to world government", likening it to a "puppet of the New World Order."[216] It also proposed breaking all institutional ties back to the Treaty of Rome, while it returned to supporting a common European currency to rival the United States dollar.[216] Further, it rejected the possible accession of Turkey to the EU.[216] The FN was also one of several parties that backed France's 2005 rejection of the Treaty for a European Constitution. In other issues, Le Pen opposed the invasions of Iraq, led by the United States, both in the 1991 Gulf War and the 2003 Iraq War.[198] He visited Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 1990, and subsequently considered him a friend.[217]

Marine Le Pen advocated France leaving the euro (along with Spain, Greece and Portugal) – although that policy has been dropped in 2019.[218][219] She also wants to reintroduce customs borders and has campaigned against allowing dual citizenship.[220] During both the 2010–2011 Ivorian crisis and the 2011 Libyan civil war, she opposed the French military involvements.[203]

Russia and Ukraine

Marine Le Pen described Russian President Vladimir Putin as a "defender of the Christian heritage of European civilisation."[221] The National Front considers that Ukraine has been subjugated by the United States, through the Revolution of Dignity. The National Front denounces anti-Russian feelings in Eastern Europe and the submission of Western Europe to "Washington's" interests in the region.[222] Marine Le Pen is very critical against the threats of sanctions directed by the international community against Russia: "European countries should seek a solution through diplomacy rather than making threats that could lead to an escalation." She argues that the United States is leading a new Cold War against Russia. She sees no other solution for peace in Ukraine than to organise a kind of federation that would allow each region to have a large degree of autonomy.[223] She thinks Ukraine should be sovereign and free as any other nation.[224]

Luke Harding wrote in The Guardian that the National Front's MEPs were a "pro-Russian bloc."[225] In 2014, the Nouvel Observateur said that the Russian government considered the National Front "capable of seizing power in France and changing the course of European history in Moscow's favour."[226] According to the French media, party leaders had frequent contact with Russian ambassador Alexander Orlov and Marine Le Pen made multiple trips to Moscow.[227] In May 2015, one of her advisers, Emmanuel Leroy, attended an event in Donetsk marking the "independence" of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic.[228]

European Union

Since their entry into the European Parliament in 1979, the National Rally has promoted a message of being pro-Europe, but anti-EU.[229] However, in 2019 the proposal that France leave the Eurozone and the EU was removed from the party's manifesto, which has since called for "reform from within" the union.[230][231][232] The party advocates that EU legislation should be initiated by the Council of the EU rather than the European Commission, and that French laws should have primacy over EU laws.[28][193]

NATO

The party's stance on NATO has varied throughout the years, under Jean-Marie Le Pen's leadership the party advocated for a complete withdrawal from the organization, while under Marine Le Pen's leadership the party has softened its stance to instead advocate leaving NATO's integrated military command structure, which France joined in 2009.[233][234][235][236]

Electoral reform and referendums

The National Rally has advocated for full proportional representation in France, claiming that the two-round system disenfranchises voters. In early 2021, Marine Le Pen, along with centrist politician François Bayrou and green politician Julien Bayou, cosigned a letter asking President Emmanuel Macron to implement proportional representation for future elections.[237]

The party advocates referendums on key issues such as the death penalty, immigration policy and constitutional change. In 2022, Marie Le Pen stated, "“I want the referendum to become a classic operating tool."[193]

Controversies

View on Nazi history and relations with Jewish groups

There has been a difference between Marine Le Pen's and her father's views concerning the Holocaust and Jews. In 2005, Jean-Marie Le Pen wrote in the far-right weekly magazine Rivarol that the German occupation of France "was not particularly inhumane, even if there were a few blunders, inevitable in a country of 640,000 square kilometres (250,000 sq. mi.)" and in 1987 referred to the Nazi gas chambers as "a point of detail of the history of the Second World War". He has repeated the latter claim several times.[238] In 2004, Bruno Gollnisch said, "I do not question the existence of concentration camps but historians could discuss the number of deaths. As to the existence of gas chambers, it is up to historians to determine" (de se déterminer).[239] Jean-Marie Le Pen was fined for these remarks, but Gollnisch was found not guilty by the Court of Cassation.[240][241][242] The leader of the party, Marine Le Pen, distanced herself for a time from the party machine in protest at her father's comments.[243] In response to her father's remarks Marine Le Pen referred to the Holocaust as the "abomination of abominations".[244]

During the 2012 presidential election, Marine Le Pen sought the support of Jewish people in France.[245] Interviewed by the Israeli daily newspaper Haaretz about the fact that some of her European senior colleagues had formed alliances with, and visited, some Israeli settlers and groups, Marine Le Pen said: "The shared concern about radical Islam explains the relationship ... but it is possible that behind it is also the need of the visitors from Europe to change their image in their countries ... As far as their partners in Israel are concerned, I myself don't understand the idea of continuing to develop the settlements. I consider it a political mistake and would like to make it clear in this context that we must have the right to criticise the policy of the State of Israel – just as we are allowed to criticise any sovereign country – without it being considered anti-Semitism. After all, the National Front has always been Zionistic and always defended Israel's right to exist". She has opposed the emigration of French Jews to Israel in response to radical Islam, explaining: "The Jews of France are Frenchmen, they're at home here, and they must stay here and not emigrate. The country is obligated to provide solutions against the development of radical Islam in problematic areas".[246]

Czecho-Russian bank loan

In November 2014, Marine Le Pen confirmed that the party had received a €9 million loan from the First Czech Russian Bank (FCRB) in Moscow to the National Front.[247][248] Senior FN officials from the party's political bureau informed Mediapart that this was the first instalment of a €40 million loan, although Marine Le Pen has disputed this.[221][248] The Independent said the loans "take Moscow's attempt to influence the internal politics of the EU to a new level."[221] Reinhard Bütikofer stated, "It's remarkable that a political party from the motherland of freedom can be funded by Putin's sphere—the largest European enemy of freedom."[249] Marine Le Pen argued that it was not a donation from the Russian government but a loan from a private Russian bank because no other bank would give her a loan. This loan is meant to prepare future electoral campaigns and to be repaid progressively. Marine Le Pen has publicly disclosed all the rejection letters that French banks have sent to her concerning her loan requests.[250] Since November 2014, she insists that if a French bank agrees to give her a loan, she would break her contract with the FCBR, but she has not received any other counter-propositions.[251] Le Pen accused the banks of collusion with the government.[250] In April 2015, a Russian hacker group published texts and emails between Timur Prokopenko, a member of Putin's administration, and Konstantin Rykov, a former Duma deputy with ties to France, discussing Russian financial support to the National Front in exchange for its support of Russia's annexation of Crimea, though this has not coalesced.[252]

Links with the far-right

A 2019 undercover investigation by Al Jazeera uncovered links between high-ranking National Rally figures and Generation Identity, a far-right group. In secretly taped conversations, National Rally leaders endorsed goals of Generation Identity and discussed plans to "remigrate" immigrants, effectively sending them back to their countries of origin, if National Rally came to power. Christelle Lechevalier, a National Rally Member of the European Parliament (MEP), said many National Rally leaders held similar views as the GI, but sought to hide them from voters.[253]

International relations

The FN has been part of several groups in the European Parliament. The first group it helped co-establish was the European Right after the 1984 election, which also consisted of the Italian Social Movement (MSI), its early inspiration, and the Greek National Political Union.[254] Following the 1989 election, it teamed up with the German Republicans and the Belgian Vlaams Blok in a new European Right group, while the MSI left due to the Germans' arrival.[255] As the MSI evolved into the National Alliance, it chose to distance itself from the FN.[256] From 1999 to 2001, the FN was a member of the Technical Group of Independents. In 2007, it was part of the short-lived Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty group. Between the mentioned groups, the party sat among the non-affiliated Non-Inscrits. It is part of the Identity and Democracy group, which also includes the Freedom Party of Austria, Italian Northern League, Vlaams Belang, the Alternative for Germany, the Czech Freedom and Direct Democracy, the Dutch Freedom Party, the Conservative People's Party of Estonia, the Finns Party, and the Danish People's Party. It was formerly known as the Europe of Nations and Freedom group, during which time it also included the Polish Congress of the New Right, a former member of the UK Independence Party and a former member of Romania's Conservative Party. They have also been part of the Identity and Democracy Party (formerly the Movement for a Europe of Nations and Freedom) since 2014, which additionally includes Slovakia's We Are Family and the Bulgarian Volya Movement.

During Jean-Marie Le Pen's presidency, the party has also been active in establishing extra-parliamentary confederations. During the FN's 1997 national congress, the FN established the loose Euronat group, which consisted of a variety of European right-wing parties. Having failed to cooperate in the European Parliament, Le Pen sought in the mid-1990s to initiate contacts with other far-right parties, including from non-EU countries. The FN drew most support in Central and Eastern Europe, and Le Pen visited the Turkish Welfare Party. The significant Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) refused to join the efforts, as Jörg Haider sought to distance himself from Le Pen, and later attempted to build a separate group.[217][257] In 2009, the FN joined the Alliance of European National Movements; it left the alliance since. Along with some other European parties, the FN in 2010 visited Japan's Issuikai ("right-wing") movement and the Yasukuni Shrine.[258]

At a conference in 2011, the two new leaders of the FN and the FPÖ, Marine Le Pen and Heinz-Christian Strache, announced deeper cooperation between their parties.[259] Pursuing her de-demonisation policy, in October 2011, Marine Le Pen, as new president of the National Front, joined the European Alliance for Freedom (EAF).[260] The EAF is a pan-European sovereigntist platform founded late 2010 that is recognised by the European Parliament. The EAF has individual members linked to the Austrian Freedom Party of Heinz-Christian Strache, the UK Independence Party, and other movements such as the Sweden Democrats, Vlaams Belang (Belgian Flanders), Germany (Bürger in Wut), and Slovakia (Slovak National Party).[261]

During her visit to the United States, Marine Le Pen met two Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives associated with the Tea Party movement, Joe Walsh, who is known for his strong stance against Islam, which Domenic Powell argues, rises to Islamophobia[262] and three-time presidential candidate Ron Paul, whom Le Pen complimented for his stance on the gold standard.[263] In February 2017, two more conservative Republican Congressmen, Steve King and Dana Rohrabacher, also met with Le Pen in Paris.[264] The party also has ties to Steve Bannon, who served as White House Chief Strategist under President Donald Trump.[265][266]

In 2017, Marine Le Pen met with and was interviewed for the British radio station LBC by former UK Independence Party leader Nigel Farage, who had previously been critical of the FN.[267] Apart from the party's membership in the Identity and Democracy parliamentary group and the Identity and Democracy Party, the RN also has contacts with Giorgia Meloni's Brothers of Italy,[268] Krasimir Karakachanov's IMRO – Bulgarian National Movement,[269] Nenad Popović's Serbian People's Party,[270] and Santiago Abascal's Vox in Spain.[271]

In 2019, RN MEPs participated in the first international delegation to visit India's Jammu and Kashmir following the decision by Narendra Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party government to revoke the special status of Jammu and Kashmir. The delegation was not sanctioned by the European Parliament, and consisted mostly of right-wing populist politicians including MEPs from Vox, Alternative for Germany, the Northern League, Vlaams Belang, the British Brexit Party, and Poland's Law and Justice party.[272][273]

In October 2021, Le Pen met with Fidesz leader and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki from the Law and Justice party, and Slovenian Democratic Party leader and Slovenian Prime Minister Janez Janša.[274]

Leadership

The executive bureau features: Jordan Bardella (president), Steeve Briois (vice-president), Louis Aliot (vice-president), David Rachline (vice-president), Kévin Pfeffer (treasurer), Julien Sanchez (spokesperson), Gilles Pennelle (regional councilor), Edwige Diaz (deputy regional councilor), Hélène Laporte, Philippe Olivier, and Jean-Paul Garraud.[275]

Presidents

| No | President | Term start | Term end |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  Jean-Marie Le Pen |

1972 | 2011 |

| Jean-Marie Le Pen founded the National Front for French Unity party in 1972 and contested the Presidency of France in 1974, 1988, 1995, 2002 and 2007. He served several terms as a deputy of the National Assembly of France and a Member of the European Parliament. He later served as honorary president of the party from January 2011 to August 2015[276] | |||

| 2 | .jpg.webp) Marine Le Pen |

2011 | 2021 |

| Marine Le Pen took over as the president of the party in 2011 and contested the 2012, 2017 and 2022 French presidential elections. She served as a Member of the European Parliament from 2004 to 2017 and has served as a deputy of the National Assembly of France since 2017. Under her leadership the party was renamed National Rally in 2018. | |||

| 3 | .jpg.webp) Jordan Bardella |

2021 | Incumbent |

| Jordan Bardella became acting president of RN after Marine Le Pen launched her presidential campaign in September 2021.[277] He was elected president in November 2022. | |||

Vice Presidents

The party had five vice presidents between July 2012 and March 2018 (against three previously).[278]

- Alain Jamet, first vice president (2011–2014)[279]

- Louis Aliot, in charge of training and demonstrations (2011–2018)[280]

- Marie-Christine Arnautu, in charge of social affairs (2011–2018)[281]

- Jean-François Jalkh, in charge of elections and electoral litigations (2012–2018)[282]

- Florian Philippot, in charge of strategy and communication (2012–2017)[283]

- Steeve Briois, in charge of local executives and supervision (2014–2018)[284]

- Jordan Bardella, (2019–2022)

In March 2018, the position of vice-president replaced that of General Secretary.[276] It became a duo in June 2019:[285]

- Steeve Briois (2018–present)

- Louis Aliot

- David Rachline

General Secretaries

The position of General Secretary was held between 1972 and 2018:[276]

- Alain Robert (1972–1973)

- Dominique Chaboche (1973–1976)

- Victor Barthélémy (1976–1978)

- Alain Renault (1978–1980)

- Pierre Gérard (1980–1981)

- Jean-Pierre Stirbois (1981–1988)

- Carl Lang (1988–1995)

- Bruno Gollnisch (1995–2005)

- Louis Aliot (2005–2010)

- Jean-François Jalkh (2010–2011; interim period during the internal campaign)

- Steeve Briois (2011–2014)

- Nicolas Bay (2014–2017)

- Steeve Briois (2017–2018)

Elected representatives

As of February 2023, National Rally has 88 MPs. They sit in the National Assembly as members of the National Rally group.

Election results

The National Front was a marginal party in 1973, the first election it participated in, but the party made its breakthrough in the 1984 European Parliament election, where it won 11% of the vote and ten MEPs. Following this election, the party's support mostly ranged from around 10 to 15%, although it saw a drop to around 5% in some late 2000s elections. Since 2010, the party's support seems to have increased towards its former heights. The party managed to advance to the final round of the 2002 French presidential election, although it failed to attract much more support after the initial first round vote. In the late 2000s the party suffered decline in elections. Under Marine Le Pen's presidency the party has increased its vote share significantly. The National Front came first in a national election for the first time during the 2014 European elections, when it gained 24% of the vote. During the 2017 presidential election the party advanced to the second round of the election for the second time, and doubled the percentage it received in the 2002 presidential election, earning 34%. In the 2019 European elections the rebranded National Rally retained its spot as first party.

National Assembly

| National Assembly | |||||||

| Election year | Leader | 1st round votes | % | 2nd round votes | % | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973[286] | Jean-Marie Le Pen | 108,616 | 0.5% | — | — | 0 / 491 |

|

| 1978[286] | 82,743 | 0.3% | — | — | 0 / 491 |

||

| 1981[286] | 44,414 | 0.2% | — | — | 0 / 491 |

||

| 1986[286] | 2,703,442 | 9.6% | — | — | 35 / 573 |

||

| 1988[286] | 2,359,528 | 9.6% | — | — | 1 / 577 |

||

| 1993[287] | 3,155,702 | 12.7% | 1,168,143 | 5.8% | 0 / 577 |

||

| 1997[287] | 3,791,063 | 14.9% | 1,435,186 | 5.7% | 1 / 577 |

||

| 2002[287] | 2,873,390 | 11.1% | 393,205 | 1.9% | 0 / 577 |

||

| 2007[287] | 1,116,136 | 4.3% | 17,107 | 0.1% | 0 / 577 |

||

| 2012 | Marine Le Pen | 3,528,373 | 13.6% | 842,684 | 3.7% | 2 / 577 |

|

| 2017 | 2,990,454 | 13.2% | 1,590,858 | 8.8% | 8 / 577 |

||

| 2022 | 4,248,626 | 18.7% | 3,589,465 | 17.3% | 89 / 577 |

||

Presidential

| Election year | Candidate | First round | Second round | Result | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Rank | Votes | % | Rank | |||

| 1974 | Jean-Marie Le Pen | 190,921 | 0.75 | — | Lost | |||

| 1981 | did not participate | |||||||

| 1988 | Jean-Marie Le Pen | 4,375,894 | 14.39 | — | Lost | |||

| 1995 | 4,570,838 | 15.00 | — | Lost | ||||

| 2002 | 4,804,713 | 16.86 | 5,525,032 | 17.70 | Lost | |||

| 2007 | 3,834,530 | 10.44 | — | Lost | ||||

| 2012 | Marine Le Pen | 6,421,426 | 17.90 | — | Lost | |||

| 2017 | 7,678,491 | 21.30 | 10,638,475 | 33.90 | Lost | |||

| 2022 | 8,133,828 | 23.15 | 13,288,686 | 41.45 | Lost | |||

Regional councils

| Regional councils | ||||||||||

| Election | Leader | 1st round votes | % | 2nd round votes | % | Seats | Regional presidencies | +/– | Winning party | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1986[286] | Jean-Marie Le Pen | 2,654,390 | 9.7% | — | — | 137 / 1,880 |

0 / 26 |

Union for French Democracy | 4th | |

| 1992[286] | 3,396,141 | 13.9% | — | — | 239 / 1,880 |

0 / 26 |

Rally for the Republic | 3rd | ||

| 1998[286][288] | 3,270,118 | 15.3% | — | — | 275 / 1,880 |

0 / 26 |

||||

| 2004[289] | 3,564,064 | 14.7% | 3,200,194 | 12.4% | 156 / 1,880 |

0 / 26 |

Socialist Party | |||

| 2010[290] | 2,223,800 | 11.4% | 1,943,307 | 9.2% | 118 / 1,749 |

0 / 26 |

||||

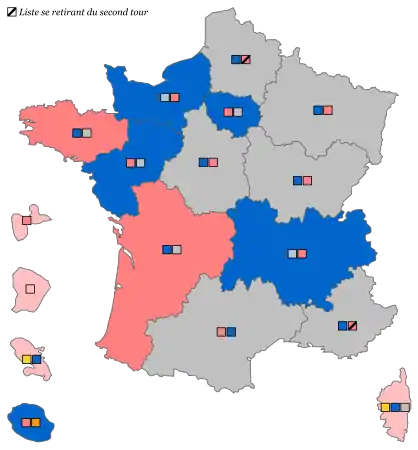

| 2015[291] | Marine Le Pen | 6,018,672 | 27.7% | 6,820,147 | 27.1% | 358 / 1,722 |

0 / 18 |

The Republicans | ||

| 2021[292][293] | 2,743,497 | 18.7% | 2,908,253 | 19.1% | 252 / 1,926 |

0 / 18 |

Leftist Union + Ecologists | |||

European Parliament

| European Parliament See also Elections to the European Parliament | ||||||||

| Election | Leader | European alliance | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Winning party | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984[286] | Jean-Marie Le Pen | DR | 2,210,334 | 11.0% | 10 / 81 |

Union for French Democracy | 4th | |

| 1989[286] | 2,129,668 | 11.7% | 10 / 81 |

3rd | ||||

| 1994[286] | NI | 2,050,086 | 10.5% | 11 / 87 |

5th | |||

| 1999[286] | TGI | 1,005,113 | 5.7% | 5 / 87 |

Socialist Party | 8th | ||

| 2004[286] | NI | 1,684,792 | 9.8% | 7 / 78 |

4th | |||

| 2009[287] | EURONAT | 1,091,691 | 6.3% | 3 / 74 |

Union for a Popular Movement | 6th | ||

| 2014[294] | Marine Le Pen | EAF | 4,712,461 | 24.9% | 24 / 74 |

National Front | 1st | |

| 2019 | Jordan Bardella | ID | 5,286,939 | 23.3% | 23 / 79 |

|||

Notes

- The party was formerly part of the European Right (1984–1989), the European Right (1989–1994), the Technical Group of Independents (1999–2001) and Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty (2007).

- Other customary colours[5] include the following:

Black Grey Brown Red

References

- "Vive la difference – has France's Front National changed?". BBC News. 5 December 2015. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Lignier, Sebastien (22 June 2023). "Le Rassemblement national bat son record d'adhésions". Valeurs actuelles (in French). Retrieved 4 August 2023.

-

- Jens Rydgren (2008). "France: The Front National, Ethnonationalism and Populism". Twenty-First Century Populism. Link.springer.com. pp. 166–180. doi:10.1057/9780230592100_11. ISBN 978-1-349-28476-4.

- "'The nation state is back': Front National's Marine Le Pen rides on global mood". the Guardian. 18 September 2016.

- "Marine Le Pen says sanctions on Russia are not working". The Economist.

-

- "Depuis 2011, le FN est devenu "protectionniste au sens large"". Liberation. 21 April 2014. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Taylor, Adam (8 January 2015). "French far-right leader seeks to reintroduce death penalty after Charlie Hebdo attack". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Garnier, Christophe-Cécil (7 December 2015). "Quelle doit être la couleur du Front national sur les cartes électorales?" (in French). Slate. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- Ivaldi, Gilles (18 May 2016). "A new course for the French radical right? The Front National and "de-demonisation"". In Akkerman, Tjitske; de Lange, Sarah L.; Rooduijn, Matthijs (eds.). Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Into the Mainstream?. Routledge. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-317-41978-5. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Forchtner, Bernhard (September 2019). "Climate change and the far right". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change. 10 (5): e604. doi:10.1002/wcc.604. S2CID 202196807.

- Forchtner, Bernhard (2020). The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-10402-9. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Abridged list of reliable sources that refer to National Rally as far-right:

Academic:

- Azéma, Jean-Pierre; Winock, Michel (1994). Histoire de l'extrême droite en France. Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 9782020232005.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017

- DeClair 1999

- Hobolt, Sara; De Vries, Catherine (16 June 2020). Political Entrepreneurs: The Rise of Challenger Parties in Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691194752.

- Joly, Bertrand (2008). Nationalistes et Conservateurs en France, 1885–1902. Les Indes Savantes.

- Kitschelt, Herbert; McGann, Anthony (1995). The radical right in Western Europe: a comparative analysis. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. pp. 91–120. ISBN 0472106635.

- McGann, Anthony; Kitschelt, Herbert (1997). The Radical Right in Western Europe A Comparative Analysis. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472084418.

- Mayer, Nonna (January 2013). "From Jean-Marie to Marine Le Pen: Electoral Change on the Far Right". Parliamentary Affairs. 66 (1): 160–178. doi:10.1093/pa/gss071.

- Messina, Anthony (2015). "The political and policy impacts of extreme right parties in time and context". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 38 (8): 1355–1361. doi:10.1080/01419870.2015.1016071. S2CID 143522149.

- Mondon, Aurelien (2015). "The French secular hypocrisy: the extreme right, the Republic and the battle for hegemony". Patterns of Prejudice. '49 (4): 392–413. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2015.1069063. S2CID 146600042.

- Mudde, Cas (25 October 2019). The Far Right Today and The ideology of the extreme right. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1509536856.

- Rydgren, Jens (2008). France: The Front National, Ethnonationalism and Populism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781349284764.

- Shields 2007

- Simmons, Harvey G. (1996). The French National Front: The Extremist Challenge To Democracy. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813389790.

- Williams, Michelle Hale (January 2011). "A new era for French far right politics? Comparing the FN under two Le Pens and The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties in West European Democracies". Análise Social. 201 (1): 679–695.

- "Victory for France's conservatives in local elections". Deutsche Welle. AP, AFP, Reuters. 30 March 2015. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Bamat, Joseph (23 April 2011). "New poll shows far right could squeeze out Sarkozy". France 24. Archived from the original on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- Dodman, Benjamin (23 November 2014). "France's cash-strapped far right turns to Russian lender". France24. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015.

- Erlanger, Steven; de Freytas-Tamura, Kimiko (17 December 2016). "E.U. Faces Its Next Big Test as France's Election Looms". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Frosch, Jon (7 March 2011). "Far-right's Marine Le Pen leads in shock new poll". France 24. Archived from the original on 10 March 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- Lichfield, John (1 March 2015). "Rise of the French far right: Front National party could make sweeping gains at this month's local elections". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Meichtry, Stacy; Bisserbe, Noemie (19 August 2015). "Le Pen Family Drama Splits France's Far Right National Front Party". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Polakow-Suransky, Sasha. "The ruthlessly effective rebranding of Europe's new far right". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Tourret, Nathalie (14 August 2010). "Japanese and European far right gathers in Tokyo". France 24. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- Van, Sonia (29 July 2011). "France – A Guide to Europe's Right-Wing Parties and Extremist Groups". Time. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- "Jews in Le Pen's party make blacklist of candidates with neo-Nazi ties". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Factsheet: National Rally (Rassemblement National, previously Front National or National Front)". Bridge Initiative. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- GALBREATH, MEGAN (2017). "An Analysis of Donald Trump and Marine le Pen". Harvard International Review. 38 (3): 7–9. ISSN 0739-1854. JSTOR 26528673.

Marine Le Pen, leader of the far-right National Front

- "National Rally". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Davies 2012, pp. 46–55.

- "22 MESURES POUR 2022 (22 measures for 2022)". Rassemblement National. 2022. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- Shields 2007, p. 229.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 46, 56 and 71.

- "Marine Le Pen temporarily steps down as Front National leader to concentrate on presidential bid". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- "France's far right replaces Le Pen with Jordan Bardella – DW – 11/05/2022". dw.com. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- Softening image:

- "The French National Front: On its way to power?". Policy-network.net. 22 January 2015. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

Devil of the Republic:- Craw, Victoria (23 January 2015). "Marine Le Pen National Front leader | Who is Marine Le Pen?". News.com.au. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

Holocaust denial:- "Jean-Marie Le Pen fined again for dismissing Holocaust as 'detail'". theguardian. 6 April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

Islamophobia:- "Jean-Marie Le Pen condamné pour incitation à la haine raciale". Le Monde.fr. lemonde.fr. 24 February 2005. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Jean-Marie suspension and expulsion:

- "France National Front: Jean-Marie Le Pen suspended". BBC News. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Jean-Marie Le Pen, exclu du Front national, fera "bien évidemment" un recours en justice". L'Express. 20 August 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- "Local elections confirm a quarter of French voters support Front National". openeurope.org.uk. 23 March 2015. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- John Lichfield (1 March 2015). "Rise of the French far right: Front National party could make sweeping gains at this month's local elections". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "France – Poll gives France's far-right National Front party boost ahead of regional vote". France24.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Marine Le Pen propose de renommer le FN " Rassemblement national "". Le Monde. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Marine Le Pen annonce que le Front national devient Rassemblement national". Le Monde. 1 June 2018. Archived from the original on 1 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Barbière, Cécile (16 April 2019). "Le Pen's Rassemblement National revises stance towards EU and the euro". euractiv.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- "Après l'euro et le Frexit, nouveau revirement européen de Marine Le Pen". Le HuffPost (in French). 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 21 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- "Marine Le Pen n'envisage plus de suspendre les accords de Schengen". 20minutes.fr (in French). 12 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- Davies 2012, pp. 31–35.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 21–24.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 25–27.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 27–31.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 13–17.

- Day, Alan John (2002). Political parties of the world. University of Michigan. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-9536278-7-5.

- Shields 2007, pp. 163–164.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 36 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 169.

- Shields 2007, pp. 159, 169.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 31, 36–37.

- Kitschelt & McGann 1997, p. 94.

- DeClair 1999, p. 13.

- De Boissieu, Laurent. "Chronologie du Front National FN". France Politique. ISSN 1765-2898. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 38 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 170.

- Shields 2007, p. 171.

- DeClair 1999, p. 39.

- Shields 2007, pp. 173 f.

- Shields 2007, pp. 174 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 175.

- Shields 2007, p. 176 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 183.

- Shields 2007, pp. 177, 185.

- Shields 2007, p. 177.

- DeClair 1999, p. 41.

- Shields 2007, p. 178 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 180–184.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 121.

- Shields 2007, pp. 181, 184.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 106.

- Shields 2007, pp. 179–180, 185–187.

- DeClair 1999, p. 43.

- Shields 2007, p. 181 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 182.

- Shields 2007, pp. 182, 198.

- Shields 2007, p. 182 f.

- White, John Kenneth (1998). Political parties and the collapse of the old orders. SUNY. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-7914-4067-4.

- Birch, Jonah (19 August 2015). "The Many Lives of François Mitterrand". Jacobin. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Kitschelt & McGann 1997, pp. 95–98.

- Shields 2007, p. 195.

- DeClair 1999, p. 60.

- Shields 2007, p. 196.

- DeClair 1999, p. 61.

- Kitschelt & McGann 1997, p. 100.

- DeClair 1999, p. 76.

- DeClair 1999, p. 62.

- DeClair 1999, p. 63.

- Shields 2007, p. 194.

- Shields 2007, p. 230.

- Shields 2007, p. 197.

- Shields 2007, p. 209.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 66.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 64–66.

- Shields 2007, p. 216.

- DeClair 1999, p. 80.

- Fabre, Clarisse (4 May 2002). "Entre 1986 et 1988, les députés FN voulaient rétablir la peine de mort et instaurer la préférence nationale" (In French). Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- Shields 2007, p. 217.

- Shields 2007, p. 219.

- DeClair 1999, p. 68.

- Shields 2007, p. 224.

- DeClair 1999, p. 70.

- Shields 2007, p. 227.

- Shields 2007, pp. 223 f.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 89.

- DeClair 1999, p. 90.

- Shields 2007, p. 233.

- Shields 2007, p. 234.

- Shields 2007, pp. 235–237.

- Shields 2007, p. 237.

- Shields 2007, pp. 236 f.

- DeClair 1999, p. 93.

- Shields 2007, pp. 247–249.

- DeClair 1999, pp. 94 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 252.

- Shields 2007, pp. 260 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 261.

- Shields 2007, pp. 262 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 263.

- DeClair 1999, p. 101.

- Shields 2007, p. 264.

- DeClair 1999, p. 104.

- DeClair 1999, p. 103.

- "Archives". Archives.lesoir.be. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Shields 2007, pp. 264 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 275.

- Shields 2007, p. 276.

- Shields 2007, pp. 271 f.

- Shields 2007, pp. 277–279.

- Shields 2007, p. 279.

- McLean, Iain; McMillan, Alistair (2009). "National Front (France)". The concise Oxford dictionary of politics. Oxford University. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-19-920516-5. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Shields 2007, p. 280.

- Shields 2007, pp. 280 f.

- Samuel, Henry (11 September 2008). "French far-right leader Jean-Marie Le Pen sets retirement date". The Telegraph. Paris. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- Shields 2007, p. 281.

- Shields 2007, p. 282.

- Shields 2007, p. 283.

- Shields 2007, p. 284.

- Shields 2007, pp. 288 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 289.

- Shields 2007, p. 291.

- Shields 2007, pp. 291–293.

- Shields 2007, pp. 292 f.

- Shields 2007, p. 297.

- Shields 2007, p. 298.

- Shields 2007, p. 300.

- Riché, Pascal (29 April 2008). "Après le "Paquebot", Le Pen vend sa 605 blindée sur eBay". Rue 89 (in French). Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Sulzer, Alexandre (30 April 2008). "La Peugeot de Le Pen à nouveau mise en vente sur ebay". 20 Minutes. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Samuel, Henry (15 March 2010). "Far-Right National Front performs well in French regional elections". The Telegraph. Paris. Archived from the original on 18 March 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- "Marine Le Pen 'chosen to lead Frances National Front'". BBC News. 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.