Count (baseball)

In baseball and softball, the count refers to the number of balls and strikes a batter has in their current plate appearance. If the count reaches three strikes, the batter strikes out; if the count reaches four balls, the batter earns a base on balls (a "walk").[lower-alpha 1]

Usage

The count is usually announced as a pair of numbers, for example, 3–1 (pronounced as "three and one"), with the first number being the number of balls and the second being the number of strikes. Zero is almost always pronounced as "oh". The count is often used as adjective—an individual pitch may be referred to by the count prior to its delivery; for example, a pitch thrown with a count of three balls and one strike would be called a "three-one pitch" or a "three-and-one pitch".[lower-alpha 2]

A count of 0–0 is rarely expressed as such, as the count is typically not mentioned until at least one pitch has been thrown.[lower-alpha 3] A count of 1–1 or 2–2 may be described as even. A count of 3–2 is full, which is discussed below.

The home plate umpire will signal the count with the number of balls on his left hand, and the number of strikes on his right hand. (As a result, it reads backwards when viewed from the pitcher's point of view.) Individual umpires vary in how frequently they give this signal; it is often done as a reminder when there has been a slight delay between pitches, such as due to the batter stepping out of the batter's box. It can also be a signal to the scoreboard operator that an incorrect count is being shown on the board. Some umpires may also give the count verbally, although usually only the batter and catcher can hear it.

Significance

An important part of baseball statistics is measuring which counts are most likely to produce favorable outcomes for the pitcher or the hitter. Counts of 3–1 and 2–0 are considered advantageous to hitters ("hitters' counts"), because the pitcher—faced with the possibility of walking the batter—is more likely to throw a ball in the strike zone, particularly a fastball. Counts with two strikes (except 3–2) are considered advantageous to pitchers ("pitchers' counts"). An 0–2 count is very favorable to a pitcher. In such a count, the pitcher has the freedom to throw one (or sometimes two) pitches out of the strike zone intentionally, in an attempt to get the batter to "chase" the pitch (swing at it), and strike out.

Somewhat surprisingly, in general, a 3–0 count tends to yield fewer hittable pitches, depending on the situation. (Baseball fans have often suggested that this is because umpires are reluctant to call four straight balls and as a result "ease up" on the fourth pitch, treating it as having a wider strike zone.) Often, batters will "take" (not swing at) a 3–0 pitch, since the pitcher has missed the strike zone three straight times already, and a fourth would earn the batter a walk. This is a sound strategy because the batter is more likely to eventually reach base even if the count becomes 3–1 than he is if he puts the ball in play on 3–0.[2] In some situations, it is also advantageous to take on 2–0 and 3–1.[2]

Full count

A full count is the common name for a count where the batter has three balls and two strikes. Since a batter may maintain two strikes indefinitely by hitting foul balls,[lower-alpha 4] a full count does not always mean that only five pitches have been thrown, nor does it ensure that there is only one more pitch to be thrown in the plate appearance.

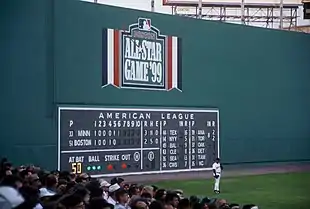

The full count term may derive from older scoreboards, which had spaces (rather than numerals) to denote up to three balls and up to two strikes, as this is the maximum number of each that can be accrued during an ongoing plate appearance. Many scoreboards still use light bulbs for this purpose, thus a 3–2 count means that all the bulbs are fully lit up. The alternate term full house (more commonly used in softball) is likely to have been influenced by the full house hand in poker, consisting of three of a kind and a pair.

A pitch thrown with a full count is often referred to as a "payoff pitch", since it is likely to be a good pitch for the batter to swing at. With three balls already called by the umpire, the pitcher cannot afford to miss the strike zone, which would result in ball four and a walk for the batter.

When there are two outs in an inning, any baserunners susceptible to being putout on a force play will normally run on any 3–2 pitch, even if they are not very fast runners. This is because either the batter will walk thus forcing such runners to advance, strike out to end the inning, foul off the pitch (allowing runners to return to their original bases), or put the ball into play.

Notes

- Arguing as to whether a pitch was a ball or a strike (which is a judgment call by the umpire) is strictly prohibited by Major League Baseball (MLB) rules. Such an infringement, known as "arguing balls and strikes," will quickly lead to a warning from the umpire, and the player or manager may be ejected from the game if they continue to argue.[1]

- Players may shorten the count even further, stating it simply as a number, for example 31 ("thirty-one") for 3–1.

- Some leagues, most commonly in slow-pitch softball, treat plate appearances as starting with non-zero counts—for example, 1–1—to speed up the game.

- Slow-pitch softball rules normally stipulate that a foul ball hit with two strikes results in the batter being called out.

References

- "Official Baseball Rules". Major League Baseball. Section 9. The Umpire.

- Bickel, J. Eric. 2009. On the decision to take a pitch. Decision Anal. 6(3) 186–193.