Southern fulmar

The southern fulmar (Fulmarus glacialoides) is a seabird of the Southern Hemisphere. Along with the northern fulmar, F. glacialis, it belongs to the fulmar genus Fulmarus in the family Procellariidae, the true petrels. It is also known as the Antarctic fulmar[1] or silver-grey fulmar.[2]

| Southern fulmar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Procellariiformes |

| Family: | Procellariidae |

| Genus: | Fulmarus |

| Species: | F. glacialoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Fulmarus glacialoides (Smith, 1840) | |

| |

It is largely pale grey above and white below with a distinctive white patch on the wing. It breeds on the coast of Antarctica and on surrounding islands, moving north in winter. It nests in colonies on cliffs, laying a single egg on a ledge or crevice. Its diet includes krill, fish and squid picked from the water's surface.

Taxonomy

The southern fulmar formally described and illustrated in 1840 by the Scottish zoologist Andrew Smith in his major work Illustrations of the Zoology of South Africa. He placed it with all the other petrels in the genus Procellaria and coined the binomial name Procellaria glacialoides.[3] The southern fulmar is now placed with the northern fulmar in the genus Fulmarus that was introduced in 1826 by the English naturalist James Stephens.[4][5] The genus name comes from the Old Norse Fúlmár meaning "foul-mew" or "foul-gull" because of the birds' habit of ejecting a foul-smelling oil. The specific epithet glacialoides combines the specific glacialis introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1761 for the northern fulmar with the Ancient Greek -oidēs meaning "resembling". [6] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[5] Molecular data suggests that the two fulmar species diverged during the Pleistocene epoch.[7]

Description

It is a fairly large, bulky petrel, 45 to 50 cm (18–20 in) long with a wingspan of 110 to 120 cm (43–47 in).[8] The male has an average weight of 795 g (28.0 oz) while the smaller female weighs around 740 g (26 oz). These weights increase to 1,005 and 932 g (35.5 and 32.9 oz) at the start of a shift incubating the eggs.[7] The male has a wing length of 34 cm (13 in), bill length of 44.6 mm (1.76 in), tarsus length of 52.1 mm (2.05 in) and tail length of 12.4 cm (4.88 in). The female has a wing length of 33.9 cm (13.3 in), bill length of 43 mm (1.69 in), tarsus length of 51.5 mm (2.03 in) and tail length of 12.1 cm (4.8 in).[7]

The bird flies with a mixture of shallow flaps and long glides, often looking down to scan the water. The wings are fairly broad and rounded and are held stiff. The plumage is mainly pale silvery-grey above and white below. The head is white with a pale grey crown. The wingtips are blackish with a large white patch and the wings have a dark rear edge. The legs and feet are pale blue. The bill is pink with a black tip and dark bluish naricorns. First-year birds have a more slender bill than the adults.[9]

It is usually silent but has loud, cackling calls which are uttered at the nest or in feeding flocks. Courting birds produce soft droning and guttural croaking calls.

Distribution and habitat

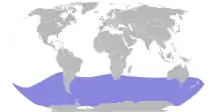

There are colonies on a number of the islands around Antarctica such as the South Sandwich Islands, South Orkney Islands, South Shetland Islands, Bouvet Island, and Peter I Island. The bird also breeds at several sites along the mainland coast of Antarctica.[10]

At sea, it mainly occurs along the outer edge of the pack ice in summer with water temperatures of −1.5 to 0.5 °C.[7] In winter, it regularly ranges north to around 40°S latitude. It occurs further north in the cool waters of the Humboldt Current, reaching Peru. Small numbers are seen off the coasts of South Africa, southern Australia and New Zealand. Many birds can be washed up on beaches after storms. There are several unconfirmed reports from the west coast of North America.[11]

It is a common species with a population of at least 4 million individuals.[7] About a million pairs breed on the South Sandwich Islands alone.[12] The species is not thought to be at risk of extinction and is classed as least concern by Birdlife International.[13]

Behaviour

Breeding

The breeding colonies may contain hundreds of birds and are on cliffs in ice-free areas with the birds arriving in October. The courtship display consists of a pair sitting alongside each other while calling, waving their heads and nibbling and preening each other. The nest is a shallow scrape lined with stone chips. It is built in a spot sheltered from the wind on a ledge or scree slope or in a crevice. A single, white egg is laid during late November or early December. It measures 76 by 51 mm (2.99 by 2.01 in) and weighs about 103 g (3.6 oz).[9] It is incubated for about 45 days with both parents taking turns in stints of 3–9 days. The down feathers of the young birds are initially white apart from a blue-grey wash on the mantle. The second set of down feathers is grey on the upperparts and flanks while the rest of the underparts and the forehead remain white.[9] The young fledge after around 52 days. Poor weather can lead to high mortality rates among eggs and chicks and they are also preyed on by skuas and sheathbills.[14] Breeding success increases as the parents mature, improving from 48% at age 6–8 to 87% at age 18–20.[7]

Feeding

Southern fulmars frequently gather in flocks, often with other species of seabird such as Cape petrels, when there is a concentration of food like a school of krill or around whaling ships and trawlers. Krill and other crustaceans are the most important component of the diet but the species also feeds on small fish such as the Antarctic silverfish and squid such as Psychroteuthis, Gonatus and Galiteuthis.[14] Food is usually picked from the surface of the water but the bird will occasionally dive.[14]

References

- BirdLife International (2018). "Fulmarus glacialoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22697870A132609920. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22697870A132609920.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Hockey, P.A.R. (1994). Birds of Southern Africa, Checklist and Alternative Names. Cape Town: Struik. p. 47. ISBN 1-86825-631-6.

- Smith, Andrew (1840). Illustrations of the Zoology of South Africa. Vol. 2, Aves. London: Smith, Elder. Plate 51, text.

- Stephens, James Francis (1826). Shaw, George (ed.). General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History. Vol. 13, Part 1. London: Kearsley et al. p. 236.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2022). "Petrels, albatrosses". IOC World Bird List Version 12.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 166, 173. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Brooke, M. (2004). "Procellariidae". Albatrosses And Petrels Across The World. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-850125-0.

- Pizzey, Graham; Knight, Frank (1997). The Graham Pizzey & Frank Knight Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. London, UK: HarperCollins.

- Watson, George E. (1975). Birds of the Antarctic and Subantarctic. Washington, D.C. USA: American Geophysical Union.

- Harrison, Peter (1987). A Field Guide to Seabirds of the World. Lexington, Massachusetts: The Stephen Greene Press.

- Banks, Richard C. (1998). "Supposed northern records of the Southern Fulmar". Western Birds. 19 (3): 121–124.

- Heather, Barrie D.; Robertson, Hugh A. (1997). The field guide to the birds of New Zealand. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- BirdLife International (2009). "Southern Fulmar – BirdLife Species Factsheet". Data Zone. Retrieved 17 Jul 2009.

- del Hoyo, Joseph; Elliot, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (1992). Ostrich to ducks. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 1. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.