Herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant specimens and associated data used for scientific study.[2]

.jpg.webp)

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sheet of paper (called exsiccatum, plur. exsiccata) but, depending upon the material, may also be stored in boxes or kept in alcohol or other preservative.[3] The specimens in a herbarium are often used as reference material in describing plant taxa; some specimens may be types.

The same term is often used in mycology to describe an equivalent collection of preserved fungi, otherwise known as a fungarium.[4] A xylarium is a herbarium specialising in specimens of wood.[5] The term hortorium (as in the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium) has occasionally been applied to a herbarium specialising in preserving material of horticultural origin.[6]

History

The making of herbaria is an ancient phenomenon, at least six centuries old, although the techniques have changed little, and has been an important step in the transformation of the study of plants from a branch of medicine to an independent discipline, and to make available plant material from far away places and over a long period of time.[7]

The oldest traditions of making herbarium collections have been traced to Italy. The Bologna physician and botanist, Luca Ghini (1490–1556) reintroduced the study of actual plants as opposed to relying on classical texts, such as Dioscorides, which lacked sufficient accuracy for identification. At first, he needed to make available plant material, even in winter, hence his Hortus hiemalis (winter garden) or Hortus siccus (dry garden). He and his students placed freshly gathered plants between two sheets of paper and applied pressure to flatten them and absorb moisture. The dried specimen was then glued onto a page in a book and annotated.[8] This practice was supplemented by the parallel development of the Hortus simplicium or Orto botanico (botanical garden) to supply material, which he established at the University of Pisa in 1544.[9]

Although Ghini's herbarium has not survived,[10] the oldest extant herbarium is that of Gherardo Cibo from around 1532.[11] While most of the early herbaria were prepared with sheets bound into books, Carl Linnaeus came up with the idea of maintaining them on free sheets that allowed their easy re-ordering within cabinets.[12]

Specimen preservation

Commensurate with the need to identify the specimen, it is essential to include in a herbarium sheet as much of the plant as possible (e.g., roots, flowers, stems, leaves, seed, and fruit), or at least representative parts of them in the case of large specimens. To preserve their form and colour, plants collected in the field are carefully arranged and spread flat between thin sheets, known as flimsies (equivalent to sheets of newsprint), and dried, usually in a plant press, between blotters or absorbent paper.[13]

During the drying process the specimens are retained within their flimsies at all times to minimise damage, and only the thicker, absorbent drying sheets are replaced. For some plants it may prove helpful to allow the fresh specimen to wilt slightly before being arranged for the press. An opportunity to check, rearrange and further lay out the specimen to best reveal the required features of the plant occurs when the damp absorbent sheets are changed during the drying/pressing process.

The specimens, which are then mounted on sheets of stiff white paper, are labelled with all essential data, such as date and place found, description of the plant, altitude, and special habitat conditions. The sheet is then placed in a protective case. As a precaution against insect attack, the pressed plant is frozen or poisoned, and the case disinfected.

Certain groups of plants are soft, bulky, or otherwise not amenable to drying and mounting on sheets. For these plants, other methods of preparation and storage may be used. For example, conifer cones and palm fronds may be stored in labelled boxes. Representative flowers or fruits may be pickled in formaldehyde to preserve their three-dimensional structure. Small specimens, such as mosses and lichens, are often air-dried and packaged in small paper envelopes.[3]

No matter the method of preservation, detailed information on where and when the plant was collected, habitat, color (since it may fade over time), and the name of the collector is usually included.

The value of a herbarium is much enhanced by the possession of types, that is, the original specimens on which the study of a species was founded. Thus the herbarium at the British Museum, which is especially rich in the earlier collections made in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, contains the types of many species founded by the earlier workers in botany. It is also rich in types of Australian plants from the collections of Sir Joseph Banks and Robert Brown, and contains in addition many valuable modern collections.[14]

Collections management

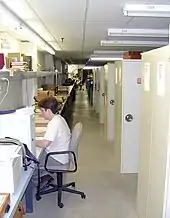

Most herbaria utilize a standard system of organizing their specimens into herbarium cases. Specimen sheets are stacked in groups by the species to which they belong and placed into a large lightweight folder that is labelled on the bottom edge. Groups of species folders are then placed together into larger, heavier folders by genus. The genus folders are then sorted by taxonomic family according to the standard system selected for use by the herbarium and placed into pigeonholes in herbarium cabinets.[15]

Locating a specimen filed in the herbarium requires knowing the nomenclature and classification used by the herbarium. It also requires familiarity with possible name changes that have occurred since the specimen was collected, since the specimen may be filed under an older name.

Modern herbaria often maintain electronic databases of their collections. Many herbaria have initiatives to digitize specimens to produce a virtual herbarium. These records and images are made publicly accessible via the Internet when possible.

Uses

Herbarium collections can have great significance and value to science, and have many uses.[16][17] Herbaria have long been essential for the study of plant taxonomy, the study of geographic distributions, and the stabilizing of nomenclature. Linnaeus's herbarium, which contains over 4,000 types, now belongs to the Linnean Society in England.[18] Modern scientists continue to develop novel, non-traditional uses for herbarium specimens that extend beyond what the original collectors could have anticipated.[19]

Specimens housed in herbaria may be used to catalogue or identify the flora of an area. A large collection from a single area is used in writing a field guide or manual to aid in the identification of plants that grow there. With more specimens available, the author or the guide will better understand the variability of form in the plants and the natural distribution over which the plants grow.

Herbaria also preserve a historical record of change in vegetation over time. In some cases, plants become extinct in one area or may become extinct altogether. In such cases, specimens preserved in a herbarium can represent the only record of the plant's original distribution. Environmental scientists make use of such data to track changes in climate and human impact.

Herbaria have also proven very useful as source of plant DNA for use in taxonomy and molecular systematics. Even ancient fungaria represent a source for DNA-barcoding of ancient samples.[20]

Many kinds of scientists and naturalists use herbaria to preserve voucher specimens; representative samples of plants used in a particular study to demonstrate precisely the source of their data, or to enable confirmation of identification at a future date.[13]

They may also be a repository of viable seeds for rare species.[21]

Institutional herbaria

Many universities, museums, and botanical gardens maintain herbaria. Each is assigned an alphabetic code in the Index Herbariorum, between one and eight letters long.[22]

The largest herbaria in the world, in approximate order of decreasing size, are:

- Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (P) (Paris, France)

- New York Botanical Garden (NY) (Bronx, New York, US)

- Komarov Botanical Institute (LE) (St. Petersburg, Russia)

- Royal Botanic Gardens (K) (Kew, England, UK)

- Missouri Botanical Garden (MO) (St. Louis, Missouri, US)

- Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de la Ville de Genève (G) (Geneva, Switzerland)

- Naturalis Biodiversity Center (Nationaal Herbarium Nederland) (AMD, L, U, WAG) (Leiden, Netherlands)

- The Natural History Museum (BM) (London, England, UK)

- Harvard University (HUH) (Cambridge, Massachusetts, US)

- Museum of Natural History of Vienna (W) (Vienna, Austria)

- Swedish Museum of Natural History (S) (Stockholm, Sweden)

- United States National Herbarium (Smithsonian Institution) (US) (Washington, DC, US)

- Université Montpellier (MPU) (Montpellier, France)

- Université Claude Bernard (LY) (Villeurbanne, France)

- Herbarium Universitatis Florentinae (FI) (Florence, Italy)

- National Botanic Garden of Belgium (BR) (Meise, Belgium)

- University of Helsinki (H) (Helsinki, Finland)

- Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem, Zentraleinrichtung der Freien Universität Berlin (B) (Berlin, Germany)

- The Field Museum (F) (Chicago, Illinois, US)

- University of Copenhagen (C) (Copenhagen, Denmark)

- Chinese National Herbarium, (Chinese Academy of Sciences) (PE) (Beijing, People's Republic of China)

- University and Jepson Herbaria (UC/JEPS) (Berkeley, California, US)

- Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh (E) (Edinburgh, Scotland, UK)

- Herbarium Bogoriense (BO) (Bogor, West Java, Indonesia)

- Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden (Central National Herbarium (CAL), Howrah, India)

- Herbarium Hamburgense (HBG) (Hamburg, Germany)

See also

References

- "Herbarius continens species plantarum tum patriarum tum exoticarum ad vivum prout nascuntur in horto infirmariae celeberrimae Abbatiae Diligemensis". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- Edinburgh, Royal Botanic Garden. "Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh - What is a herbarium". www.rbge.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- "Preparing and Storing Herbarium Specimens" (PDF). Conserve O Gram. National Park Service. November 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- "Fungarium". www.kew.org. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Wood collection (xylarium)". www.kew.org. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Archived from the original on 17 July 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium". plantbio.cals.cornell.edu. Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Thiers 2020, p. 13.

- Thiers 2020, pp. 15–16.

- Thiers 2020, p. 16.

- Thiers 2020, p. 20.

- Sprague & Nelmes 1931, p. 546.

- Müller-Wille, Staffan (2006-06-01). "Linnaeus' herbarium cabinet: a piece of furniture and its function". Endeavour. 30 (2): 60–64. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2006.03.001. PMID 16600379.

- Chater, Arthur O. "Collecting and Pressing Specimens" (PDF). www.bsbi.org.uk. Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Herbarium", Parkstone Press International 2014

- "HerbWeb - What is a Herbarium". apps.kew.org. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- Funk, Vicki (January 2003). "The Importance of Herbaria". Plant Science Bulletin. 49 (3): 94. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Funk, Vicki. "100 Uses for an Herbarium (Well at Least 72)" (PDF). peabody.yale.edu. The Yale University Herbarium. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Linnaean Collections". The Linnean Society. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- Heberling, J. Mason; Isaac, Bonnie L. (2017). "Herbarium specimens as exaptations: New uses for old collections". American Journal of Botany. 104 (7): 963–965. doi:10.3732/ajb.1700125. ISSN 1537-2197. PMID 28701296.

- Forin, Niccolò; Nigris, Sebastiano; Voyron, Samuele; Girlanda, Mariangela; Vizzini, Alfredo; Casadoro, Giorgio; Baldan, Barbara (2018). "Next Generation Sequencing of Ancient Fungal Specimens: The Case of the Saccardo Mycological Herbarium". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 6. doi:10.3389/fevo.2018.00129.

- Wiley online library

- "Learn more - The William & Lynda Steere Herbarium". Index Herbariorum, New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved 2023-05-16.

Bibliography

- Thiers, Barbara M. (2020). Herbarium: The Quest to Preserve and Classify the World's Plants. Timber Press. ISBN 978-1-64326-052-5.

- Sprague, T. A.; Nelmes, E. (1 October 1931). "The Herbal of Leonhart Fuchs". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 48 (325): 545–642. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1931.tb00596.x.

External links

- For links to a specific herbarium or institution, see the List of herbaria.

- Index Herbariorum

- Linnean Herbarium

- Lamarck's Herbarium (online database with 20,000 sheets in HD)

- French Herbaria Network

- Montpellier Herbarium