Gürdal Duyar

Gürdal Duyar (20 August 1935 – 18 April 2004) was a Turkish sculptor who is known for his monuments to Atatürk and his busts of famous people. His art is characterized as a modern expressionist style that is balanced with abstraction. He is considered one of the pioneers of modern figurative sculpture in Turkey. Duyar was also a painter and is noted for his sketches but his best-known works are the public sculptures that are placed in Istanbul's parks and public squares.

Gürdal Duyar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 August 1935 Nişantaşı, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Died | 18 April 2004 (aged 68) Nişantaşı, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Resting place | Zincirlikuyu Cemetery |

| Education | Rudolf Belling, Ali Hadi Bara |

| Alma mater | State Academy of Fine Arts |

| Organization | Turkish High Sculptors Society |

| Known for | Sculpture, painting, sketching |

| Works |

|

| Movement | Republic Era Turkish Sculpture (Turkish: Cumhuriyet Dönemi Heykel Sanatı) |

| Family | Neşe Aybey (sister) |

| Signature | |

| |

Duyar was a student of Rudolf Belling and Ali Hadi Bara at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul, after graduating from which he spent some time abroad. At the start of his career as a freelance artist, Duyar worked on sculpture, especially busts, in Belgium, France and Switzerland. He later returned to Turkey, where he became known for his Atatürk monuments, including his Uşak Atatürk Monument (1965). He made several more Atatürk monuments in Turkey and held the first exhibition of his work in 1968.

Late in his career, many of Duyar's sculptures were damaged, removed or lost; these include the controversial 1974 removal of Güzel İstanbul. Duyar was a member of the joined the Turkish High Sculptors Society and was commissioned for several works; these include the Borazan İsmail Monument (1972), Kayseri Atatürk Monument (1974) and Âşık Seyrani Monument (1976). Duyar exhibited his sculptures and paintings, both individually and alongside other artists. His later major sculptures are Şairler Sofası (1998), Abdi İpekçi Peace Monument (2000) and Necati Cumalı (2002), and many of his busts that can be found in Sanatçılar Park. Duyar died in 2004 in Istanbul at age 69.

Early life and work

Gürdal Duyar was born on 20 August 1935 in Istanbul; he was the youngest child of Fikri Duyar and Nezahat Duyar (née Erişkin). His older siblings were Erdal Duyar (1927-1975) and Neşe Aybey (1930-2015).[1][2][3] His sister Neşe became a well-known miniature artist who graduated from and later taught at the State Academy of Fine Arts.[4]

Duyar attended the İstanbul Haydarpaşa School. After finishing middle school in 1951, he took high-school-level classes at the sculpture faculty of the State Academy of Fine Arts,[5] which was possible due to a special government regulation.[6] At the academy, which in now Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, he was a student of German sculptor Rudolf Belling.[6][7] In 1952, Duyar entered the high-sculpture division of the academy and studied in the atelier of Ali Hadi Bara.[6][8][9] At the academy he also learned from Zühtü Müridoğlu, and İlhan Koman.[10] When Duyar was 17, one of his sculptures was exhibited in the Painting and Sculpture Museum at Dolmabahçe Palace and at 19, he had a work exhibited in the State Painting and Sculpture Museum.[7][11] He graduated from the academy in 1959 and became a freelance artist.[6][10]

After finishing his studies at the academy, Duyar worked in Belgium, France and Switzerland for some time, sculpting busts and studying architecture.[10][12][13] During this time abroad he developed his stonework skills while working with the sculptor León Perrin, a close friend of Le Corbisier.[10][13][14] One of his works was erected on Paris' Place de la Concorde.[15][16] One of his early major busts was a 1.5-metre (4.9 ft)-tall bust of Atatürk that was commissioned by the Düzce municipality in 1962.[note 1] His early plaster busts Portrait of Bilge (Turkish: Bilge’nin portresi) and Head of a Woman (Turkish: Kadın Başı) were also exhibited at İstanbul State Art and Sculpture Museum.[18][19]

Career breakthrough (1963–1973)

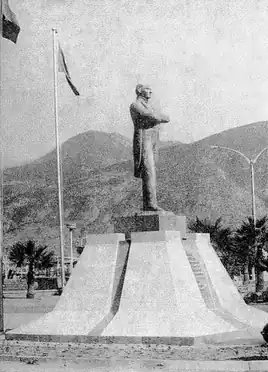

Duyar returned to Istanbul around 1963.[13][note 2] At that time, a campaign by the newspaper Milliyet was raising money to erect monuments to Atatürk in some provinces of Turkey. Duyar was the youngest participant in the competition to select the sculptors of these monuments.[10][21] He was one of eight winners and was allocated to Uşak province.[22] Duyar's design was an 7.5-metre (25 ft)-tall sculpture depicting a caped Ataturk with his left hand raised and right hand in motion.[23][24]

Duyar's Atatürk monument was different from typical Atatürk monuments of the time, which were in a more-established academic style.[25][26] The sculpture was erected on 10 November 1965 in the same park that also contains Duyar's Monument to the Unknown Soldier (1964).[18][27][28] The Uşak Atatürk Monument was Duyar's first major commission.[18][29] During the next decade, he was commissioned to create many similar monuments around Turkey.[note 3] becoming well-known as a sculptor of Atatürk.[32]

Duyar's first personal exhibition was at the Taksim Art Gallery in 1968 and his second was held in 1970.[42][43] He also participated in group exhibitions, including those organised by the Turkish High Sculptors Society, of which he was a member.[32]

.jpg.webp) Monument to the Unknown Soldier (1964).

Monument to the Unknown Soldier (1964). The Burhaniye Atatürk Monument (1967) before it was removed.

The Burhaniye Atatürk Monument (1967) before it was removed. The Ataturk and Mining Monument (1971) in the garden of the MTA in Ankara.

The Ataturk and Mining Monument (1971) in the garden of the MTA in Ankara. The İskenderun Ataturk Monument (1972).

The İskenderun Ataturk Monument (1972).

Mid-career (1973–1987)

As the 50th anniversary of the Turkish Republic neared, celebrations were planned. Duyar, by this time an established sculptor and well-known in Istanbul, was chosen as one of several sculptors to make works for the occasion.[44] Duyar proposed a sculpture named Güzel İstanbul that would personify Istanbul as a nude woman[45] whose arms would be bound by a chain, representing the defensive chain constructed by the Byzantines to close off the Golden Horn from the Ottoman fleet.[46] The woman would be depicted breaking the chain, representing both the Ottoman takeover of Istanbul from Byzantine rule and the emancipation of women. The organising committee accepted the proposal and the sculpture was erected in 1974 in a public square in Karaköy.[47]

The sculpture became the subject of heated debate due to its nudity, leading to its removal after nine days at the behest of a conservative faction of the national coalition government.[47] According to Seyhun Topuz, this affair almost brought an end to the coalition.[48] Güzel İstanbul was eventually moved to Yıldız Park where it is placed with its back towards the park and its face towards a wall in a damaged state.[49][50][51] The Association of Turkish Sculptors organized a nude-centric exhibition as a protest against the removal of Güzel İstanbul.[52][53]

Around 1972, Duyar made a monument for the town Burhaniye to memorialise Borazan İsmail, a Çanakkale and Independence War fighter who had recently died.[note 4] A sculpture named Süvari Atatürk Anıtı (Mounted Atatürk Monument) was erected on Kayseri's Republic Square in 1974.[56][57][58][59] It was covered in a tarp for years and was later moved to the Kültürpark.[60] In 1976, Kayseri municipality commissioned Duyar to place a modern Atatürk sculpture next to the old Atatürk sculpture of the city.[61] The sculpture depicted the War of Independence and incorporated a depiction of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk wearing a kalpak. Despite being appreciated at the time of its completion, it was found split in two, and was left in that state.[54][note 5] The same year, the mayor of Develi Mehmet Özdemir commissioned Duyar to make a sculpture of the Develi-born Turkish folk poet Âşık Seyrani. This sculpture was erected on 30 April 1976 in a park in front of Çarşı Mosque and became a symbol of Develi district.[63][64][note 6]

Throughout the 1970s, some of Duyar's sculptures were moved or hidden following the removals of Güzel İstanbul and the War of Independence Monument in Kayseri, such as the sculpture of Tamburi Cemil Bey in Emirgan Park, which was removed at the behest of a manager;[note 7] and the sculpture of Borazan İsmail in Burhaniye, which was removed at the behest of the mayor.[54] Some of his earlier Atatürk monuments were also removed, such as his 1967 Burhaniye monument.[33]

Duyar was involved in a 1980 design interventions for the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Ankara as a jury member involved in the evaluation of the submitted proposals.[note 8]

Duyar continued to sculpt busts, such as one of theatrical actor Bedia Muvahhit; she had portraits painted before but had rejected offers to be depicted in sculpture. She accepted an offer by Duyar in 1980 and posed at Duyar's workshop in three-hour-long sessions.[66] Muvahhit was also later gifted a sculpture Duyar was commissioned to make.[note 9] Duyar also sculpted a bust of short-story writer Sait Faik Abasıyanık, which now stands in front of Abasıyanık's former house in Burgazada that is now a museum. [3][35][68] Duyar's other busts include one of Franz Schubert that has decorates the concert hall of the White Villa at Emirgan Park since 1983,[69] and a bust of İdil Biret.[70]

In 1984, Kemal Özkan, a renowned circumcision doctor, commissioned Duyar to make a sculpture for the garden of a building in Levent, which was inaugurated on 18 September that year.[71] In 1985, Duyar held an exhibition, displaying almost 30 years of his work including six drawings, 16 busts, 30 figures and 60 previously unseen oil paintings. Over the next few years, he held several other exhibitions and participated in group exhibitions.[9]

Later career (1987–2004) and death

In the late 1980s, Duyar discovered Emel Say, who was not yet an established artist. She had finished a painting of Maui by her mother Zehra Say, a famous painter who had been unable to finish the work due to Alzheimer's disease. When Duyar saw the painting at an exhibition at Çiçek Bar, he asked who had altered it. Say replied she had retouched it a little but Duyar replied; "it seems that you have been a painter all along". Duyar had a significant influence on Say's career, and hers and Duyar's works were exhibited together at the inaugural exhibition of Asmalımescit Art Gallery in 1995.[72][73]

In 1995, Duyar's bronze sculptural relief of the poet Gunnar Ekelöf was placed in the garden of the Swedish Research Institute in the grounds of the Swedish Consulate General in Istanbul.[74][75][76][note 10] Duyar initially did not want to make the sculpture but after visiting an atelier by invitation of the architect Erkan Güngören, he accepted the commission. The sculpture was originally located in the Çiçek Bar and was moved to the Swedish Consulate General.[78][79] In 1997, on the 111th Anniversary of the Fevziye Mektepleri, an Atatürk monument by Duyar was inaugurated in the Nişantaşı Campus of the Özel Işık Lisesi school.[80]

In 1998 Duyar sculpted Şairler Sofası for the Hall of Poets park within Vişnezade, which was opened that year. The sculpture depicts the poets Behçet Necatigil, Sabahattin Kudret Aksal, Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı, Oktay Rıfat, Orhan Veli, Neyzen Tevfik and Nigâr Hanım together.[81][note 11]

In 2000, Şişli municipality commissioned Duyar to create a monument to the editor-in-chief of Milliyet Abdi İpekçi to be erected where the journalist was killed 20 years earlier. Duyar's 3.5-metre (11 ft)-tall Abdi İpekçi Peace Monument, a bronze sculpture on a 70-centimetre (28 in) granite base.[83] It depicts two students—one male and one female—holding a bust of İpekçi, and above it, a dove on the top of an arch symbolizing peace. The municipality erected the monument on 1 February 2000 in Nişantaşı on what is now called Abdi İpekçi Avenue.[3][84]

In 2001, Beşiktaş municipality commissioned Duyar for a sculpture to memorialize writer Necati Cumalı shortly after his death. The sculpture, which was sponsored by Türkiye İş Bankası, was to be placed in Şairler Sofası park.[85] Duyar created a bronze sculpture of Cumalı, which was inaugurated in a ceremony in 2002 on the 81st anniversary of Cumalı’s birth.[85][86][87] Cumalı's wife Berrin expressed her appreciation of the sculpture, stating Cumalı was "born again today".[85] Akatlar İstanbul Artists Park was opened on 13 June 2003, and incorporates many of Duyar's sculptures, including busts of artists Kemal Sunal, Barış Manço, Sadri Alışık, Bedia Muvahhit and Kuzgun Acar.[3][35][88]

.jpg.webp) Duyar's Şairler Sofası (1998) in 2022

Duyar's Şairler Sofası (1998) in 2022.JPG.webp) The Abdi İpekçi Peace Monument (2000) in 2006

The Abdi İpekçi Peace Monument (2000) in 2006 Duyar's Necati Cumalı sculpture (2002) in 2017

Duyar's Necati Cumalı sculpture (2002) in 2017.jpg.webp) Duyar's bust of Barış Manço in 2019.

Duyar's bust of Barış Manço in 2019.

On 18 April 2004, after a month of treatment at the American Hospital in Istanbul, Duyar died due to lung cancer.[35][89] The sculptors association organized a memorial ceremony for him in the morning at Vişnezade poets park in Beşiktaş.[12] Then after the noon prayer at Teşvikiye Mosque, he was laid to rest at Zincirlikuyu Cemetery.[35][62]

Style and position in sculpture history

Duyar is a primary example of the Turkish school of sculpture, which was formed under the influence of Zühtü Müridoğlu and Ali Hadi Bara. This school saw the rise of abstractionism, and the use of non-classical tools and methods of sculpture.[90][91] Duyar and his classmates, including Kuzgun Acar, Ali Teoman Germaner, Füsun Onur and Tamer Başoğlu, increased the dynamism of sculpture in Turkey and expanded its role in the art world.[92] They are known as the pioneers of abstract sculpture in Turkey.[93]

Duyar was well-known for his monumental sculptures of Atatürk, busts and other sculpted portraits. He experimented with new techniques and sought to use the natural flow of his materials. His monuments were considered contemporary in style, in contrast with the more-widespread traditional monuments in Turkey.[94] Duyar was talented in figurative sculpture, and his strong artistic ability was apparent in his drawing skills and was honed in his busts.[95] According to critic Nebil Özgentürk Duyar "thinks with his hands and portrays his thoughts in with clay".[96] According to fellow sculptor Hüseyin Gezer, Duyar was especially successful with busts. The character of the subject would be convincingly and expressively realized, and the busts would remain within the fluid boundaries of fine art.[6][97] Duyar's ability to capture the character of his subjects and the balance in his compositions was noted by critics, some of whom described his work as expressionist.[7][42][98][99] For figurative sculpture and busts, Duyar was lauded as one Turkey's top artists.[97]

Drawing

Duyar's drawings have been treated as secondary to his sculpture but his talent was noted during his lifetime.[95] Duyar sketched a lot, often late at night, and would leave the sketch behind.[100] At Refik restaurant, which was frequented by poet Özdemir Asaf, Duyar sketched Asaf and left the drawing behind. The work was later used as the cover of Asafs book Ça.[101][note 12] The cover of the book Şiirin Lüzumu Yok! by M. Yılmaz Öner[note 13] and the cover of the 1984 Yalçın Küçük book were also sketched by Duyar.[102][103]

Legacy

Duyar's legacy is strongest in Istanbul, where many of his sculptures continue to stand, and discourse continues around those of his works that were removed or damaged.[54] The removal of the Güzel İstanbul sculpture remains controversial.[104][105] Duyar influenced a generation of pioneering Turkish sculptors; he and his contemporaries introduced abstract and modernist concepts to the classical Turkish sculptural tradition.[90][92][93] Duyar's influence was especially strong in monumental sculpture.[94][97]

Notes

- At the time, it was the largest bust of Atatürk in Turkey.[14][17]

- The poet Cemal Süreya mentions that works of Duyar from the 1960s can also be found in the house of Nahit Hanım.[20]

-

These monuments include:

- Burhaniye (1967); a bronze Atatürk sculpture for Burhaniye/Edremit,[30][31][3] which was 3 metres (9.8 ft) tall.[32] The sculpture was removed with a bulldozer some years after it was made.[33]

- Alaşehir (1967); a bronze Atatürk sculpture at Alaşehir is 3 m (9.8 ft) tall. It depicts Atatürk in civilian dress.[3][34]

- Atatürk Mask (1971) was made for Gülhane Hospital in Ankara and is 0.9 m (3.0 ft) tall.[3][32][35]

- Atatürk ve Madencilik Anıtı (1971) (The Atatürk and Mining monument)[36][37] stands in the garden of the General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration (Turkey) in Ankara.[18][26][38] The 3.50-metre (11.5 ft) stone sculpture[32] responds to classic monumental sculpture ideals.[5][39]

- İskenderun (1972); Atatürk Monument for İskenderun[3][35][40] is 3 m (9.8 ft) tall, is made of bronze, has a stone base and depicts Atatürk wearing civilian dress.[41]

- Burhaniye was saved from destruction by the efforts of Borazan İsmail during the Turkish Independence War. The sculpture was removed around 1992 by the mayor at the time.[54][55]

- Other sources state that it was removed in the mid-90s on the grounds that it was being damaged,[61] or that it was removed in 1992 by civil authorities.[62]

- It stands 2.40 metres (7.9 ft) high, weighs 3,000 kilograms (6,600 lb), and cost 55,000 lira.[64] During the renovations of the mosque and the park, the sculpture was moved to the old market square of Develi.

- Several years prior to 1995, Duyar had made a sculpture of the composer Tanburi Cemil Bey, which should have been located at the White Villa in Emirgan Park. It was missing on his visit to the park around November 1995.[55] It had been removed at the behest of a manager.[54]

- Duyar was the only jury member from the field of sculpture. He was joined by the Architects Doğan Kuban, Ziya Payzın, Nezih Eldem, Sadun Ersin, and Interior Architect Orhan Akyürek; as well as calligrapher Emin Barın, painter Devrim Erbil and ceramicist Sadi Diren.[65]

- Duyar was also chosen by Tüm Tiyatro Sanatçıları Birliği, a union of all Turkish theater actors, to sculpt a gift to the older generation of actors in appreciation of their efforts over the years. The sculpture was to be presented by the younger generation of theater actors at Istanbul Sanat Merkezi (Istanbul Arts Center).[67]

- In conjucntion with Duyar's work, a selection of Ekelöf's poems were translated into Turkish from French by Hüseyin Baş and published as Emgion Prensi İçin Divan in 2003.[77]

- As of the day of the inauguration of the park, Duyars main sculpture was accompanied by those created by Yunus Tonkuş, and Namık Denizhan. The design for the park was done by Architect Erhan Işözen.[82]

- Özdemir Asaf (30 January 1993). Ça (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Adam Yayıncılık. ISBN 9789754181999.

- M. Yılmaz Öner (2003). Şiirin Lüzumu Yok ! (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Belge Yayıları. ISBN 9789753442886.

References

Citations

- Elibal 1973, pp. 295, 371.

- Duyar 2022.

- Durbaş 2004.

- Hürriyet 2015.

- EdebiyatSanat 2012.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, p. 196.

- Kuzucular 2012.

- Elibal 1973, pp. 295, 377.

- Köksal 1985, p. 8.

- Elibal 1973, p. 295.

- Taktak 1985, p. 5.

- Evrensel 2004.

- KimKimdir.com 2016.

- Sezer 2004.

- Şenol 1974, p. 1.

- Hayat 1974, p. 3.

- Aliyev 2016, p. 353.

- Akay 1984, pp. 1869–1870.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, p. 199.

- Karataş 2020, p. 40.

- Alsaç & Alsaç 1993, p. 72.

- Elibal 1973, p. 293.

- Dinçol et al. 1982, p. 1147.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, p. 197.

- Okumuş 2021, p. 154.

- Atatürk Anıtları 2017.

- Elibal 1973, pp. 290, 293, 380.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, pp. 16, 277.

- Elibal 1973, p. 298.

- Elibal 1973, pp. 380, 383.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, p. 278.

- Elibal 1973, p. 299.

- Arslan.

- Elibal 1973, pp. 380, 383, 299.

- Hürriyet 2004.

- Gurur 2014.

- Aliyev 2016, p. 354.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, pp. 200, 280.

- Filozof.net Encyclopedia 2017.

- Berk & Gezer 1973, p. 198.

- Elibal 1973, pp. 293, 382, 299.

- Akyunak 1968, p. 25.

- Elibal 1973, pp. 299, 381.

- Yaman 2011, p. 68.

- Güngören 2018, p. 542.

- Hürriyet 2008.

- Antmen 2009, pp. 369–372.

- Antmen 2009, p. 374.

- Kemal 1988.

- Sönmez 2013.

- Antmen 2009, p. 367.

- Üstünipek 2019.

- Pınarbaş 2021, p. 1829.

- Özgentürk 2004.

- Özgentürk 1995.

- Okumuş 2021, p. 329.

- Karatepe 2021, p. 144.

- Taştan et al. 2015, p. 152.

- Yalçın 2012, pp. 73–74.

- Dayıoğlu 2020, p. 124.

- Dayıoğlu 2020, pp. 113–114.

- Radikal 2004.

- Yiğit.

- Aydoğdu 2011, p. 1516.

- Demirkol 2014, p. 81.

- Milliyet 1980, p. 16.

- Oral.

- Toygar 2022.

- Cumhuriyet 1983, p. 5.

- Hızlan 2022b.

- Hızlan 2022a.

- Karakartal 2004.

- Asmalımescit 2017.

- Spring, Schimanski & Aarbakke 2021, p. 161.

- Sandell 2016, p. 70.

- Ekeloifiana 2022.

- Bodin 2014, p. 14.

- Cumhuriyet 2005, p. 4.

- Kızılkaya 2022.

- Mersinoğlu 2022f.

- Demir 1998.

- Ertem 1998.

- Şişli 2021.

- Milliyet 2000.

- Demir 2002.

- Beşiktaş 2016.

- Sezer & Özyalçıner 2010.

- Mersinoğlu 2022e.

- CNN Türk 2022.

- H62.

- Doğan 2004, p. 463.

- Sülün 2012.

- Türkçe Bilgi 2010.

- Eczacıbaşı Encyclopedia of Art 1997, p. 491.

- Dinçol et al. 1982, p. 1141.

- Özgentürk 2005.

- Celâl et al. 1997, p. 564.

- Hürriyet 2000.

- Güngören 2018, p. 543.

- Durbaş 2017.

- Durbaş 2002.

- IDEFIX 2022.

- Mersinoğlu 2022g.

- Şendul 2021, pp. 73, 118–127.

- Antmen 2009.

Print sources

- Akay, Ezel, ed. (9 July 1984). "Gürdal Duyar". Türk ve Dünya Ünlüleri Ansiklopedisi. 34 (in Turkish). Vol. 4. Maslak-Istanbul: Anadolu Yayıncılık. pp. 1869–1870. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2017 – via Issuu.

- Akyunak, Nezahat (1968). "Güzel Sanatlar Akademisinin 85. kuruluş yıldönümü" [85th Anniversary of the Fine Arts Academy] (PDF) (in Turkish). p. 25. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- Aliyev, Ilham, ed. (2016). "Duyar, Gürdal". National Encyclopedia of Azerbaijan (in Azerbaijani). Baku. pp. 353–354. ISBN 978-9952-441-12-3.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Alsaç, Birsen; Alsaç, Üstün (June 1993). "II. Bölum: Yontu. ii. Cumhuriyet Dönemi" [Section II: Statue. ii. Republic Era]. Türk Resim ve Yontu Sanatı [The Art of Turkish Painting and Statue]. Cep Üniversitesi 123 (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları. pp. 70–75. ISBN 975-470-341-8.

- "Askeri Müze'de ilk kez çağdaş sanat" (PDF). Cumhuriyet (Press Cutting). 18 September 1987. Retrieved 18 October 2022 – via Salt Research, Nur Koçak Archive.

- Aydoğan, Bilge Evrim (May 2004). "Bir Modern Zaman Çilekeşi, Gürdal Duyar" [A present day ordeal, Gürdal Duyar]. rh+ sanat (in Turkish). No. 10. Istanbul. pp. 25–29. ISSN 1303-751X.

- "Bedia Muvahhit'in büstü" [The Bust of Bedia Muvahhit]. Milliyet (in Turkish). 9 March 1980. p. 16. section "Magazin". Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Berk, Nurullah; Gezer, Hüseyin (1973). 50 Yılın Türk Resim Ve Heykeli [Turkish Painting and Sculpture of the first half century] (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Istanbul: İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları : 123.

- Celâl, Metin; Katoğlu, Murat; Özdemir, Hikmet; Tuncay, Mete; Koçak, Cemil; Ödekan, Ayla; Boratav, Korkut (1997). "4.3 Heykel" [4.3 Sculpture]. Çağdaş Türkiye 1908-1980 [Contemporary Turkey 1908-1980]. Türkiye Tarihi (in Turkish). Vol. 4. Cem Yayınevi. pp. 561–565.

- "Cumhuriyet 22 Mayıs 2005 Pazar Haberler" [Cumhuriyet 22 May 2005 Monday News]. Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). 22 May 2005. p. 4. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "Çağdaş sanat sergileri açılıyor" (PDF). Güneş. 25 September 1987. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022 – via Nur Koçak Archive, Salt Research.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Dayıoğlu, Kadir (April 2020). Kuruluşundan Günümüze Kayseri Belediye Başkanları [Mayors of Kayseri Since Its Establishment] (PDF). Kayseri Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür Yayınları Tarih Dizisi (in Turkish) (2 ed.). Kayseri Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür Yayınları. ISBN 9786059117449. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Demir, Bülent (26 November 1998). "Akaretler'de şairler parkı" [Poets Park in Akaretler] (PDF). Hürriyet (in Turkish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Dinçol, Ali; Belli, Oktay; Sevin, Veli; Özsait, Mehmet; Onurkan, Somay; Yıldız, Hakkı D.; Eyice, Semavi; Halaçoğlu, Yusuf; Baykara, Tuncer; Sözen, Metin; Sönmez, Zeki; Demiriz, Yıldız; Çağman, Filiz; Tansuğ, Sezer (1982). "Türk Resim ve Heykel Sanatı" [The Art of Turkish Painting and Sculpture]. Anadolu Uygarlıkları: Görsel Anadolu Tarihi Ansiklopedisi [Anatolian Civilizations: Visual Encyclopedia of Anatolia] (in Turkish). Istanbul: Görsel Yayınlar.

- Doğan, Kutlay (2004). Akıncılar, Çiğdem; Çelik Bayrak, B. Selen; Çağıl, Cemile; Taşyürek, Nilay (eds.). Turkey 2004. Kavaklıdere, Ankara: Directorate General of Press & Information of the Prime Ministry. ISBN 9789751936400.

- Eczacıbaşı Sanat Ansiklopedisi [Eczacıbaşı Encyclopedia of Art] (in Turkish). Vol. 1. Yapı Endüstri Merkezi Yayınları. 1997. ISBN 978-9944757096.

- Elibal, Gültekin (1973). Atatürk ve Resim – Heykel [Atatürk and Painting – Sculpture] (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları.

- Ertem, Raif (10 December 1998). "Şairler Sofası'nda Beşiktaş'ta" [At the Şairler Sofa in Beşiktaş]. Rasgele (in Turkish).

- Güngören, Elâ (2018). "The changing image of Istanbul through its monuments (1923-1973)". In Catalani, A; Nour, Z; Versaci, A; Hawkes, D; Bougdah, H; Sotoca, A; Ghoneem, M; Trapani, F (eds.). Cities' Identity Through Architecture and Arts: Proceedings of the International Conference on Cities' Identity through Architecture and Arts (CITAA 2017), May 11-13, 2017, Cairo, Egypt. CRC Press. pp. 539–544. ISBN 9781351680332.

- "Gürdal Duyar'ın Yapıtı" [A Work of Gürdal Duyar]. Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). 10 December 1983. p. 5. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

Emirgan'daki Beyaz Köşk'un konser salonunu susleyen Schubert bustu bir Turk yontu sanatcısının, Gurdal Duyar'ın vapıtı.

[The bust of Schubert, which decorates the concert hall of the Beyaz Köşk in Emirgan is a work of a Turkish sculpture artist, Gurdal Duyar.] - "Güzel İstanbul'un başına gelenler: Bir dikildi... Bir söküldü..." [What happened to Güzel Istanbul: Erected... Removed...]. Hayat (in Turkish). March 1974. p. 3 – via Salt Research.

- "İstanbul'da yıl boyu şenlik" (PDF). Cumhuriyet. 5 August 1987. Retrieved 18 October 2022 – via Nur Koçak Archive, Salt Research.

- Karataş, Cengiz (2020). "Orhan Veli'den Sevgilisi Nahit Hanım'a Mektuplar: Kısa Bir Bakış" [Letters from Orhan Veli to His Beloved Nahit Hanım: A Brief Overview]. In Sakallı, Fatih (ed.). Bir Garip Orhan Veli [A Garip Orhan Veli] (PDF) (in Turkish) (1st ed.). Ankara: İlbilge. pp. 39–50. ISBN 978-605-06090-7-3.

- Karatepe, Şükrü (May 2021). Yerli, Yusuf (ed.). "Kayseri Cumhuriyet Meydanı'nın Mekânsal Gelişimi" [Spatial Development of Kayseris Republic Square] (PDF). Düşünen Şehir (in Turkish). No. 14. Kayseri: Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality. pp. 132–147. eISSN 2564-7121. ISSN 2564-6354. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Kemal, Mehmed (29 August 1988). "Orhan Veli'nin Heykeli..." [The Sculpture of Orhan Veli]. Politika Ve Ötesi (in Turkish).

- Kınık, Zeynep R. (1991). Çekmeceler / 2 [Alos, Hale Arpacıoğlu, Mustafa Ata, Metin Deniz, Gürdal Duyar, Timur Kerim İncedayı ...] (in Turkish). İstanbul: Ak Yayınları. ISBN 9789757630197. OCLC 165630979. ISBN 975-7630195

- Köksal, Ahmet (1 March 1985). "Gürdal Duyar'ın Yapıtlari" [The works of Gürdal Duyar]. Milliyet (in Turkish). p. 8. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Kutlar, Onat (25 July 1993). "Çamurla Düşünen Adam" [The Man Who Thinks with Clay]. Cumhuriyet. Gündemdeki Sanatçı [Artist on the Agenda] (in Turkish). p. 2.

- Kültür Servisi (3 November 1990). "Bir dolapta kırk beş sanatçı" (PDF). Cumhuriyet. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022 – via Nur Koçak Archive, Salt Research.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Oral, Zeynep. "Emeğe Saygı" [Respect for Hard Work]. Sanat (in Turkish). Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- Özgentürk, Nebil (12 November 1995). "Mekanini arayan heykeller!" [Sculptures searching for their place!]. Bir İnsan Bin Hayat [A Person A Life]. Sabah (in Turkish). Istanbul. p. 36.

- Özsezgin, Kaya (1977). "Görsel Sanatçılar Derneğinin yarışması sonuçlandı" [The Visual Artists Association's competition has concluded] (PDF) (in Turkish). Retrieved 18 October 2022 – via İbrahim Örs Archive, Salt Research.

- Sezer, Sennur; Özyalçıner, Adnan (October 2010). Özmen, Gonca (ed.). Öyküleriyle İstanbul Anıtları [Istanbuls' Monuments Through their Stories]. II (in Turkish) (1 ed.). Beyoğlu/Istanbul: Evrensel Basim Yayin. ISBN 9786053312628. Retrieved 1 October 2017 – via books.google.com.

- Spring, Ulrike; Schimanski, Johan; Aarbakke, Thea (2021). Transforming Author Museums: From Sites of Pilgrimage to Cultural Hubs. Museums and Collections. Vol. 13. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781800732445. LCCN 2021017499.

- Şenol, Bahattin (11 March 1974). "«Güzel Istanbul» heykeli Karaköy Meydanına kondu" [The «Güzel Istanbul» sculpture has been placed on Karaköy Square]. Milliyet (in Turkish). p. 1.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) Alternative URL - Taştan, Abdulvahap; Cihan, Ahmet Kamil; Kılıç, Atabey; Aydoğdu, Betül; Arslan, Celil; Demir, Cenk; Çapraz, Erhan; Erarslan, Fevzi; Bolat, Gokhan; Tekiner, Halil; Bicer, Hamdi (December 2015). "At Meydanı/Pazarı". Kayseri Ansiklopedisi. 70 (in Turkish). Vol. 1. Kayseri: Kayseri Metropolitan Municipality. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-605-9117-01-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - "Yabancılar Aya İrini Kilisesi'nde Türkler Mimar Sinan Hamamı'nda" [Foreigners at Hagia Irene Church Turks at Mimar Sinan Hamam] (PDF). Cumhuriyet (in Turkish). 1 May 1987 – via Nur Koçak Archive, Salt Research.

Academic articles

- Antmen, Ahu (1 April 2009). "Türk kültüründe beden ve "Güzel İstanbul" olayı" [The body in Turkish culture and the "Beautiful Istanbul" affair]. Electronic Journal of Social Sciences (in Turkish). 8 (30): 366–375. ISSN 1304-0278. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- Aydoğdu, Betül (May 2011). Türk Edebiyatinda Seyrânî Olgusu: Develili Seyrânî ve Eserleri [The Case of Seyrânî in Turkish Literature: Seyrânî from Develi and His Works]. Institute of Social Sciences (PhD) (in Turkish). Kayseri: Erciyes University.

- Bodin, Helena (2014), ""Allt vad vi önskat": På resa i Turkiet i Gunnar Ekelöfs fotspår" ["Everything we wanted": On a trip through Turkey in the footsteps of Gunnar Ekelöf], in Hesse, Kristina J. (ed.), Dragomanen [The Dragoman] (PDF) (in Swedish), Visby: Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, pp. 13–18, ISSN 1402-358X, archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2018, retrieved 1 September 2017

- Demirkol, Hatice (2014). "A Reading on Atatürk Monument in the Grand National Assembly of Turkey: From Idealized to Realized". Art-Sanat Dergisi. Istanbul University (1): 73–99. eISSN 2148-3582.

- Okumuş, Gürkan (2021). Kentsel Arayüz-Heykel Kurgusu: Atatürk Anitlari (PDF) (MSc) (in Turkish). Bursa: Bursa Uludağ University.ORCID 0000-0002-3332-7910

- Pınarbaş, Yener (30 April 2021). "Kadın Kimliği Ve Toplumsal Sorunlarının Çağdaş Türk Sanatına Yansımaları" [Reflections Of Women's Identity And Their Social Problems On Contemporary Turkish Art]. International Refereed Journal on Social Sciences (in Turkish). 7 (40): 1827–1842. doi:10.31568/atlas.686 (inactive 1 August 2023). eISSN 2619-936X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - Sandell, Håkan (2016), "Gunnar Ekelöf och Maria-Magdalena-motivet" [Gunnar Ekelöf and the Mary Magdalene motif], in Heilo, Olof (ed.), Dragomanen [The Dragoman] (in Swedish), Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul, pp. 69–78, ISSN 1402-358X, retrieved 10 September 2022

- Sülün, Ebru Nalan (2012). Türk Heykel Sanatı'nda Yeni Dönem: 1950 ve Sonrası Üzerine [The New Era in Turkish Sculpture: 1950 and later] (Report). Türk Heykel Sanatı Dosyası (6). Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Şendul, Zahide (2021). Türkiye'de Kamusal Alanda Soyut Heykel Uygulamalarının Öncüleri Olarak Cumhuriyet'in 50. Yılında İstanbul'da Yapılmış Heykeller [The 50th Anniversary Sculptures in Istanbul as Pioneers of Public Abstract sculpture in Turkey] (PDF) (MSc) (in Turkish). Edirne: Trakya University. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- Yalçın, Recep (January 2012). Heykelle Şekillenen Kamusal Alan Ve Kayseri Örneği (PDF) (MSc). Kayseri: Erciyes University.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Yaman, Zeynep Yasa (January 2011). ""Siyasi / Estetik Silah" Olarak Kamusal Alanda Anıt Ve Heykel" [Public Monuments and Sculptures as "Political/Aesthetic Statement"] (PDF). METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture (in Turkish). 28 (1): 69–98. doi:10.4305/METU.JFA.2011.1.5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

Online sources

- "Abdi İpekçi Barış Anıtı". sisligezirehberi.com. Şişli Municipality. 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Abdi İpekçi ilkeleriyle anılacak" [Abdi İpekçi will be remembered through his principles] (in Turkish). Milliyet. 31 January 2000. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "Açık Alan Heykelleri" [Outdoor Sculptures]. besiktasgorselsanatlar.com (in Turkish). Beşiktaş Municipality. 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- Arslan, Yüksel. "Burhaniye De Kuva-yi Milliye Öldü Mü?". Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- "Asmalimescit Art Gallery". asmalimescitartgallery.com (in Turkish). 2017. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

Asmalımescit Sanat Galerisi 1995 yılında kurulmuş olup ilk sergisini Heyleltraş Gürdal Duyar ve Ressam Emel Say ikilisiyle sanatseverlere kapısını açmıştır.

[The Asmalımescit Art Gallery was established in 1995 and opened its doors to art lovers with its first exhibition by the duo of Sculptor Gürdal Duyar and Painter Emel Say.] - "Atatürk Anıtları" [Ataturk Monuments]. bilgipinarim.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Can, Mustafa (8 August 2004). "Ekelöfs själ flyter i floden Paktalos" [Ekelöf's soul floats in the river Paktalos]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Dagens Nyheter. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015.

- Cangül, Caner (2014). "Şairler Sofası Parkı'nın Şairleri" [The Poets of Şairler Sofası Park]. istanbulium.net. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Demir, Bülent (13 January 2002). "Necati Cumalı heykeli Beşiktaş'ta" [The Necati Cumalı sculpture is in Beşiktaş] (in Turkish). NTV. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Demirkaya, Mehmet (15 April 2008). "'Güzel İstanbul'un 34 Yıllık Esareti" [Güzel İstanbuls' 34 Years of Captivity]. yapi.com.tr. Milliyet. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Durbaş, Refik (31 January 2002). "Asafça'nın Şairi". Sabah. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- Durbaş, Refik (21 April 2004). "Gürdal Duyar'ın Vedası..." [Gürdal Duyar's Farewell...] (in Turkish). Sabah. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- Durbaş, Refik (26 January 2017). "Pera'nın marjinal hayaleti" [Peras Marginal Ghost]. birgun.net (in Turkish). BirGün. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- Duyar, Gürdal (8 August 2022). "Türkiye Yüksek Heykeltraşlar Cemiyetinin Hazırladığı Sanatçı Güldal Duyar'a Ait Bir Belge" [A Document Belonging to Artist Güldal Duyar, Prepared by the High Sculptors Association of Turkey [sic]]. Türkiye Yüksek Heykeltraşlar Cemiyeti. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- "Dünyayı kucaklamak isteyen adam: Özdemir Asaf" [The man who wants to embrace the world: Özdemir Asaf] (in Turkish). Dünya. 4 October 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- "Ekeloifiana- en selektiv Gunnar Ekelöf bibliografi under konstruktion" [Ekeloifiana- a selective Gunnar Ekelöf bibliography under construction] (in Swedish). Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Erbarıştıran, Tufan (16 February 2021). "Gürdal Duyar (1935-2004): Türkiye ve Sanatta Cinsellik" [Gürdal Duyar (1935-2004): Sexuality in Turkey and in Art] (in Turkish). Oggito.

- "Fine Arts From Turkey". marmara.edu.tr. Marmara University. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- Gurur (30 September 2014). "Ankara'nın Tarihsel Eserleri Nelerdir?" [What are Ankaras Historical Artifacts?]. nkfu.com. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- "Gürdal Duyar, Edebiyatsanat.com sitesi, Erişim tairhi: 28.05.2012" [Gürdal Duyar, Edebiyatsanat.com website, Access date:28.05.2012]. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Gürdal Duyar'ın heykeli" [Gürdal Duyars Sculpture] (in Turkish). Hürriyet. 28 January 2000. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- "Gürdal Duyar için..." [For Gürdal Duyar...]. evrensel.net. Evrensel. 21 April 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Gürdal Duyar Kimdir" [Who is Gürdal Duyar]. kimdirkimdir.com. 13 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Gürdal Duyar Kimdir, Hayatı, Eserleri, Hakkinda Bilgi" [Who is Gürdal Duyar, His Life, Works, Information About Him]. filozof.net. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Güzel İstanbul/Gürdal Duyar, Müstehcen Diye Kaldırıldı" [Güzel İstanbul/Gürdal Duyar, 'Removed For Being Obscene'] (in Turkish). Hürriyet. 19 December 2008.

- "Güzel İstanbul Heykeli'ni kimse görmesin diye böyle çevirdiler!" [They changed the Güzel İstanbul sculpture like this so that no one would see it!]. posta.com.tr. Posta. 28 October 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- "Heykelin duyarlı kavgacısıydı". Radikal. April 2004 – via Arkitera.

- "Heykeltıraş Gürdal Duyar öldü" [Sculptor Gürdal Duyar has died]. hurriyet.com.tr. Hürriyet. 19 April 2004. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Hızlan, Doğan (18 September 2022b). "İdil Biret'i dinleyerek yazdım" [I wrote this while listening to İdil Biret] (in Turkish). Hürriyet. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- Hızlan, Doğan (9 September 2022a). "Leylâ Erbil ile heykel serüvenimiz" [My sculpture adventure with Leylâ Erbil] (in Turkish). Hürriyet.

- Karakartal, Melike (14 December 2004). "Yarım kalan ada tablosu tamamlandı" [The unfinished island painting has been completed] (in Turkish). Hurriyet. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Kızılkaya, Muhsin (13 February 2022). "Türkiye'de heykeli dikilen tek Batılı şair!" [The only Western poet whose statue was erected in Turkey!]. Habertürk. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Kuzucular, Şahamettin (2 July 2012). "Gürdal Duyar Hayatı Sanatı" [Gürdal Duyar his life his art]. edebiyatvesanatakademisi.com. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Mersinoğlu, Mustafa Serpil. "Akatlar Sanatçılar Parkı". geni.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Mersinoğlu, Mustafa Serpil. "Fevziye Mektepleri 111 Yıl Dönümü". geni.com. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Mersinoğlu, Mustafa Serpil. "Yalçın Küçük Kitap Kapağı" [Yalçın Küçük Book Cover]. geni.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- "Modern Türk heykeli" [Modern Turkish Sculpture]. Türkçe Bilgi (in Turkish). 2 January 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "'Müstehcen' diye sürülen heykele şimdi de 'fidan sansürü'" [The sculpture that was expelled as 'obscene' now faces a 'censorship of saplings']. BirGün. 28 October 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- "Neşe Aybey 5 Ocak Pazartesi Hürriyet Bugünkü Vefat İlanı" [Neşe Aybey Monday, 5 January Hürriyet Todays Obituary]. Vefatlarimiz.com (in Turkish). Hürriyet. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- Özgentürk, Nebil (23 April 2005). "Bir heykel ustasını anmak!" [Commemorating a master sculptor] (in Turkish). Istanbul. Sabah.

- Özgentürk, Nebil (22 May 2004). "Heykeltıraşın ölümü" [Death of a sculptor] (in Turkish). Istanbul. Sabah. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- Pektaş, Nazlı (13 July 2015). "Meydanını düşleyen teras heykelleri..." [Terrace sculptures dreaming of their square...] (in Turkish). Cumhuriyet. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- Rood, Suzana; İklim, Aylin, eds. (2016). "Türk Sanatı'nda Kökler ve Temeller Galeri Eksen'de!". LİFE ART SANAT. Yaşam Kaya. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Sezer, Sennur (22 April 2004). "Gürdal Duyar için" [For Gürdal Duyar]. Evrensel.net (in Turkish). Evrensel. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Sönmez, Gökçe (August 2013). "Sürgündeki Heykel: Güzel İstanbul [Saray]" [Sculpture in Exile: Güzel İstanbul]. yildiz-teknik.blogspot.nl (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Şiirin Lüzumu Yok !". IDEFIX (in Turkish). Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- "Tarihte bugün: 18 Nisan" [Today in History: 18 April] (in Turkish). CNN Türk. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

2004: Heykeltıraş Gürdal Duyar 69 yaşında vefat etti.

[2004: The Sculptor Gürdal Duyar passed away at the age of 69.] - Toygar, Baha (2022). "Gürdal Duyar, Sait Faik Abasıyanık". Galaksi Rehber. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "Türkiye'nin en güzel 10 heykeli" [Turkey's 10 most beautiful sculptures]. hurriyet.com.tr. Hürriyet Seyahat. 19 December 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Türk Sanatı'nda Kökler ve Temeller". sozcu.com.tr. Sözcü. 19 January 2016.

- Üstünipek, Mehmet (2019). "Sculpture in Istanbul". History of Istanbul: From Antiquity to the 21st Century. Vol. 7. ISAM: Türkiye Diyanet Foundation Center for Islamic Studies. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- Yiğit, Hidayet. "Âşik Seyrânî Derneği ve Kutlama Programları" [Âşık Seyrânî Association and Celebration Events] (in Turkish). Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- Yılmaz, Tuncay (24 February 2011). "Yaşam ve devamı..." [Life and its continuation...] (in Turkish). Haber Turk. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Yılmaz, İhsan (7 September 2022). "İdil Biret büstü nasıl bulundu" [How was the bust of İdil Biret found?]. Hürriyet. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- Taktak, Yusuf. "Gürdal Duyar, Edpa Sanat Galerisi, İstanbul" (21 February 1985) [Invitation card]. Yusuf Taktak Collection, File: https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/39805. Istanbul: Salt Research. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

Further reading

- Alkan, Mehmet Ö. (2017). "Altmışlı Yıllarda Günlük Hayatın Siyaseti". In Bora, Tanıl (ed.). Türkiye'nin 1960'lı Yılları [Türkiye's 1960s] (in Turkish) (1st ed.). İletişim Yayınları. pp. 933–986. ISBN 978-975-05-2204-8.

- Gürdaş, Bora (2017). "Altmışlı Yıllarda Sanat Ortamı". In Bora, Tanıl (ed.). Türkiye'nin 1960'lı Yılları [Türkiye's 1960s] (in Turkish) (1st ed.). İletişim Yayınları. pp. 1055–1090. ISBN 978-975-05-2204-8.

- Kutlar, Onat (February 2016). "Çamurla Düşünen Adam". In Güllüoğlu, Fahri (ed.). Gündemdeki Sanatçı [Artist on the Agenda] (in Turkish) (2nd ed.). Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları. pp. 361–366. ISBN 9789753632409.

- Örer, Bige; Hoffmann, Jens; Pedrosa, Adriano; Madra, Beral (2011). Untitled (12th Istanbul Biennial), 2011 Remembering Istanbul [Isimsiz (12. Istanbul Bienali), 2011 : Istanbul 'u Hatirlamak.]. Istanbul: Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts. ISBN 9789757363965.

- Gezer, Hüseyin (1984). Cumhuriyet Dönemi Türk Heykeli [Republic Era Turkish Sculpture] (in Turkish). Istanbul: İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları. OCLC 220473477.