Joseph Gallieni

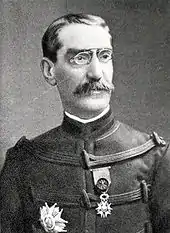

Joseph Simon Gallieni (24 April 1849 – 27 May 1916) was a French military officer, active for most of his career as a military commander and administrator in the French colonies where he wrote several books on colonial affairs.[1] Gallieni is infamous in Madagascar as the French military leader who exiled Queen Ranavalona III and abolished the 350-year-old monarchy on the island.[2]

Joseph Gallieni | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Gallieni in 1910 | |

| 112th Minister of War | |

| In office 29 October 1915 – 16 March 1916 | |

| President | Raymond Poincaré |

| Prime Minister | Aristide Briand |

| Preceded by | Alexandre Millerand |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Roques |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 April 1849 Saint-Béat, French Republic |

| Died | 27 May 1916 (aged 67) Versailles, French Republic |

| Nationality | French |

| Spouse | Marthe Savelli |

| Children | Théodore François Gaëtan Gallieni |

| Alma mater | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | French Army |

| Years of service | 1868 – 1916 |

| Rank | Division general[lower-alpha 1] |

| Commands |

|

| Battles/wars | Franco-Prussian War World War I |

He was recalled from retirement at the beginning of the First World War. As Military Governor of Paris he played an important role in the First Battle of the Marne, when Maunoury's Sixth Army, which was under his command, attacked the German west flank. A small portion of its strength was rushed to the front in commandeered Paris taxicabs.

From October 1915 he served as Minister of War, resigning from that post in March 1916 after criticizing the performance of the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre (formerly his subordinate, earlier in their careers), during the German attack on Verdun. He was made Marshal of France posthumously in 1921.

Early life and career

Gallieni was born in 1849 at Saint-Beat, in the department of Haute-Garonne, in the central Pyrenees.[3] He was of Corsican[4] and Italian descent.[5] His father, born in Pogliano Milanese, had risen from the ranks to be a captain.[6][7]

He was educated at the Prytanée Militaire in La Flèche, and then the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, becoming a second lieutenant in the 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment before serving in the Franco-Prussian War.[8]

Gallieni fought at Sedan[9] and was taken prisoner at Bazeilles, scene of the stand of the colonial marines.[10] He learned German whilst a prisoner there, and later kept a notebook in German, English and Italian called “Erinnerungen of my life di ragazzo” ("Memories of my life from boyhood [onwards]").[11]

Colonial Service

He was promoted to lieutenant in 1873. His colonial career began in 1876 in Senegal. He was promoted to captain in 1878. He led an expedition to the upper Niger. He also served in Reunion and Martinique.[12] In 1886, he had risen to the rank of lieutenant-colonel,[13] and was later appointed governor of the French Sudan, during which time he successfully quelled a rebellion by Sudanese insurgents under Mahmadu Lamine. He was outstanding at colonial penetration without open hostilities in West Africa in 1880 and 1886-8.[14]

In 1888 he was appointed to the War College. In 1892-6 he served as a colonel in French Indochina commanding the second military division of the territory in Tonkin. In 1894 he led successful French action against the nationalist leader Đề Thám, but further military action was overruled by colonial administrators after Đề Thám was accorded a local fiefdom.[15]

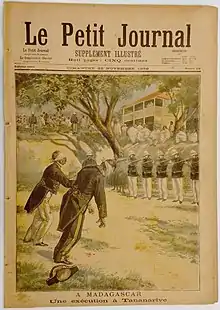

In 1896 he was promoted to General and made Governor of Madagascar, then a new French possession, where the French had just been defeated, with 4,613 soldiers dying of disease. He stayed in Madagascar with one brief interruption until 1905; his future commander Joseph Joffre served under him there.[16] In August 1896 Gallieni reorganised French forces, captured and executed several rebel leaders. Early in 1897 he abolished the Malagasy monarchy and exiled Queen Ranavalona III to Reunion.[17][18] Gallieni practised the tache d’huile (the "oil spot" method, which continues to influence counterinsurgency theory to this day[19]) and politique des races (literally, racial policy; i.e., eliminating the racial hierarchy that had prevailed and suppressing tribes that resisted French rule).[20] Initially military, his role became more administrative, building roads, a railway, markets, medical services and schools.[21]

In 1905 Gallieni defended the code de l’indigenat (the right of French officials to mete out summary punishment, including corporal punishment and confiscation of property, to individuals and to entire villages), as it administered punishment more arbitrarily and swiftly than would be possible under due legal process.[22]

Return to France

In 1905 Gallieni was appointed Military Governor of Lyon and commandant of the Army of the Alps (XIV Corps). Also in 1906 he became a member of the Conseil Superieur de la Guerre (the Superior War Council, a body of senior generals chaired by the President).[23][24]

General Victor-Constant Michel (Generalissimo, i.e. Commander-in-Chief designate of the northeast front, and Vice-President of the Superior War Council), was critical of the tactical doctrine of offensive à outrance (taking the offense to the limit). He also wanted to thrust into Belgium in the event of war, and to increase the size of the army by attaching a regiment of reservists to each regular regiment to form demi-brigades. Along with Yvon Dubail and Pol Durand, Gallieni was one of those who told War Minister Messimy that Michel must be removed.[25]

Following Michel's removal Gallieni, who was the preferred choice of Prime Minister Caillaux, declined the job of Army Chief of Staff.[26] This was partly because of scruples after having forced Michel out, partly because of age—he was two and a half years away from retirement—and partly because the Metropolitan Army might resent a colonial soldier getting the job ("une question de bouton"). His former subordinate Joffre was appointed instead.[27][28]

Pre-World War I

Gallieni commanded Fifth Army until his retirement, and protested that it was not strong enough to advance into Belgium, and that Maubeuge should be fortified more strongly. His successor Lanrezac shared his concerns.[29] After tours of the area Gallieni had failed to persuade the authorities to modernise Maubeuge.[30]

Like a number of officers with colonial experience, Gallieni wanted the French army to give up the pantalon rouge (red trousers worn by French soldiers, allegedly as a boost to morale) and adopt a less conspicuous uniform. This was vetoed on the grounds that dull uniforms might be confused with those of the enemy and might turn the army into a citizen militia like the Boers.[31]

At the 1911 manoeuvres Gallieni used air reconnaissance to capture a colonel of the Supreme War Council and his staff.[32] He expressed reservations about the limited offensive strategy. His views on fortifications, artillery, and use of information obtained from aviation and intelligence were seen as unusual views for a colonial soldier.[33]

In the same year, Gallieni was considered the logical choice for supreme commander of the French Army, but because of advanced age and poor health, he declined in favour of Joffre.[34]

His date of retirement is given as February[35] or April 1914.[36] His wife died in early summer 1914.[37]

Before the war he wrote of Joffre, “When I was riding I passed him in the bois [woods] today—on foot as usual—how fat and heavy he is; he will hardly last out his three years.” [38] He warned Joffre, correctly as it would turn out, that the Germans would come west of the Meuse in strength (i.e. make an enveloping move deep into Belgium, rather than a shallow incursion through the south-east corner of Belgium and down through the Ardennes).[39]

First World War

The Marne

Gallieni was designated as Joffre's successor “in case of emergency” on 31 July.[40] Joffre refused to have him at his headquarters, saying "He is difficult to place. I have always been under his orders. Il m’a toujours fait mousser [He always riled me]."[41] On 14 August (the day the Lorraine offensive began) Gallieni (at the insistence of War Minister Adolphe Messimy, who felt intimidated by Joffre and that the latter would be more likely to listen to his former superior) visited Joffre but was quickly palmed off onto the staff officer General Belin and his deputy Berthelot.[42][43]

Military Governor of Paris

As a condition of becoming Military governor of Paris, Gallieni demanded three active corps to defend the city. War Minister Messimy ordered Joffre to provide them on 25 August but Joffre, regarding this as interference with strategy, ignored the order. Gallieni learned from Messimy that 61st and 62nd Infantry Divisions, formerly the Paris Garrison, were being ordered north for Maunoury’s planned offensive against the German west flank near Amiens, leaving Gallieni with only territorial troops. Already in poor health, Gallieni was appointed on 26 August, not yet knowing that he did not have the resources he had demanded. However, on that day Viviani formed a new government (Union sacrée), and on 27 August the new War Minister Millerand (who had replaced Messimy largely because of the poor state of the Paris defences) visited Joffre, who promised to provide the three corps if Maunoury's attack should fail.[44][45][46]

On 28 August the “Zone of Armies” was extended to cover the Paris suburbs. From 10 am to 10:15 am Gallieni held his one and only Council of Defence, at which his military and civil cabinets, standing up and without discussion, were made to sign the order placing Paris in a state of defence. He sacked two generals in his first two days.[47]

On 2 September, the anniversary of the Battle of Sedan, the government left Paris for Bordeaux, with the evacuation continuing through the night of 2/3 September.[48] Paris was made a “camp militaire retranché”.[49] Before departing, Millerand ordered Gallieni to defend Paris “à outrance,” repeating the order when Gallieni explained that it meant destroying buildings and bridges. Gallieni later recorded that he had been certain that he was remaining behind to die.[50] That day Gallieni told Joffre that without the three corps it would be “absolutely impossible to resist.” Joffre placed Maunoury's Sixth Army, which was retreating down from the Amiens area, under Gallieni's direct command as the “Armies of Paris.” Gallieni at once drove out to inspect his new command—he was horrified by the sight of the refugees—and to visit Maunoury. Gallieni had four territorial divisions and the 185th Territorial Brigade. He soon received a Marine Artillery Brigade (mostly Breton reservist sailors) and the 84th Territorial Division. Sixth Army was soon augmented by IV Corps from Third Army. Maunoury had an active division of VII Corps, a 5,000 strong native Moroccan brigade, and four reserve divisions: 61st and 62nd under Ebener, and 55th and 56th which had fought in Lorraine. Joffre also added Drude's 45th Division of Zouaves from Algeria, who made a huge impression marching through Paris, and IV Corps from Third Army. The Prefect of Police had resigned “on grounds of health” on being ordered to remain at his post. Gallieni stayed up with his staff all night drawing up plans for Sixth Army to give battle between the Oise and Pontoise. Joffre had Millerand place Gallieni under his own command on 2 September.[51][52][53][54]

Army of Paris,

Residents of Paris,

The Military Governor of Paris,The members of the Government

of the Republic have left Paris to give

a new impulse to the national defense.

I have received the mandate to defend Paris

against the invader.

This mandate, I shall carry out to the end.

Paris, 3 September 1914

Commanding the Army of Paris,

GALLIENI

Gallieni believed that Joffre's strategy of retreating behind the Seine was “divorced from reality” as the Germans would not allow his forces enough time to rally. He spent the night of 2/3 September at his new HQ at Lycee Victor-Duruy, expecting a German attack the next day. On the morning of 3 September he learned that von Kluck was marching southeast across Paris, offering his flank to a French counterattack.[55][56] The first public proclamation on the morning of 3 September promised to defend Paris “to the last extremity.” That morning Gallieni set engineers and civilian labourers to work cutting down woods and trees, and preparing bridges and buildings for demolition to clear lines of sight for guns. For three days concrete was poured and barbed wire strung up. Even the Eiffel Tower was prepared for demolition. Paris had 2,924 guns, ranging from 155mm to 75mm. Hospitals and fire departments put on alert. Gas for three months of electricity was stockpiled, along with bread for 43 days, salt for 20 days and meat for 12 days. Pigeons were brought under state control for carrying messages. Lt-Col Dreyfus rejoined the artillery. Civilian paniquards were encouraged to leave and reconnaissance patrols were set up.[57][58][59]

Planning the Counterattack

On the night of 3–4 September Joffre sent a handwritten note to Gallieni, wanting Maunoury's Sixth Army to push east along the north bank of the Marne, although not specifying a date. This was in line with his modification of Instruction General No 4 (2 September), envisaging a giant pocket from Paris to Verdun, of which he enclosed copies to Gallieni.[60]

Gallieni decided that it was “vital to act quickly” so as not to leave Paris uncovered. At 09:10 on 4 September, based on the previous day's reports of Paris aviators, which he had passed on to Joffre, and on his own authority, he sent orders to Maunoury to be ready to move his army that afternoon (now reinforced with Drude's 45th Infantry Division) and to be ready to come to Paris for a conference. Having first informed President Poincare in Bordeaux—in Tuchman's view, to force Joffre's hand—at 9:45 am he had the first of a series of telephone calls, conducted through aides, as Joffre would not come to the phone, and Gallieni refused to speak to anyone else. Gallieni would later write that “the real Battle of the Marne was fought on the telephone.” He proposed, depending on how much further the Germans were to be allowed to advance, to attack north of the Marne on 6 September or south of the Marne on 7 September.[61][62][63]

Joffre's reply, saying he preferred the southern option (which would take a day longer as it forced Sixth Army to cross to south of the Marne, but would allow Sixth Army and the BEF to not be separated by the river), arrived too late to reach Gallieni. To ensure British cooperation Gallieni, accompanied by Maunoury, left Paris at 1 pm to drive to BEF GHQ at Melun, driving past lines of southbound cars leaving Paris. He had already received advice from the liaison officer Victor Huguet that BEF Commander-in-Chief Sir John French, influenced by BEF Chief of Staff Murray and concerned about his supply lines along the lower Seine, was unlikely to join in any offensive. They arrived at 3 pm and with some difficulty located Murray, who had no idea when Sir John, who was out visiting British I Corps, was to return and was unwilling to make any decision in his absence. In a three-hour meeting, the French generals proposed that Sixth Army was to move that afternoon, then on 5 September was to strike German IV Reserve Corps on the west flank. A provisional agreement was drawn up, with copies kept by Maunoury, Gallieni, and Lt-Col Brecard to take to GQG for Joffre's approval. The French came away with the impression that the British would not cooperate and that Murray had “une grande repugnance” for them, but he did in fact pass the plans along to Sir John. Whilst this was going on, Wilson (BEF Sub Chief of Staff) was negotiating separate plans with Franchet d’Esperey (Fifth Army, on the British right), which envisaged Sixth Army attacking north of the Marne.[64][65][66][67]

In the absence of news from Franchet d'Esperey, Joffre ordered Major Gamelin to draft orders for Maunoury to attack south of the Marne on 7 September. That evening Gallieni, who returned to Paris find Joffre's message from earlier in the day and a message from Wilson, insisted on speaking to Joffre personally on the telephone, informing him that it was too late to cancel the movement of Maunoury's Army. Joffre agreed to bring forward the Allied offensive to 6 September and to have Sixth Army attack north of the Marne instead, later writing that he had done so reluctantly as Maunoury would probably make contact with the Germans on 5 September, but that an extra day would have left the Germans in a more "disadvantageous" position. Tuchman argues that he may simply have been swayed by the dominant personality of Gallieni, his former superior. At 8:30 pm Gallieni ordered the attack by Maunoury's Army, which was in fact already under way. At 10 pm Joffre issued General Order No 6, ordering a General Allied Offensive.[68][69][70][71]

Taxicab Army and the Battle of the Ourcq

On 5 September Gallieni informed Maunoury that there was to be no retreat and issued secret orders for the destruction of important parts of Paris, including the Pont Neuf and the Pont Alexandre III.[72]

On 7 September Gallieni, concerned that with Maunoury's Sixth Army fighting out in the open, Paris was now vulnerable, telegraphed the government in Bordeaux to discuss the possible evacuation of the civilian population from the Paris suburbs, and ordered prefects and the police to find “emergency locations” for them.[73] That day Gallieni was ordered not to communicate directly with the government. This left Joffre “all-powerful” (in Gallieni's description), as he had sacked so many generals and Gallieni was his only serious rival.[74] The same day, frustrated at the slowness at which the British were advancing into the gap between the German First and Second Armies, Gallieni sent Lartigue's 8th Infantry Division to the BEF's right flank to keep contact between the BEF and Franchet d’Esperey's Fifth Army (the French and British generals of 1914 were extremely concerned at the prospect of armies being encircled and besieged, after what had happened to the French Armies at Sedan and Metz in 1870). Joffre, concerned that Gallieni might arouse Sir John's “touchiness,” sent a telegram to Lord Kitchener (British War Secretary) thanking him for Sir John's efforts.[75]

It was Gallieni's decision to send 103rd and 104th Infantry Regiments (5 battalions, part of Trentinian's 7th Infantry Division, itself part of IV Corps; most of 7th Infantry Division, including artillery, had been sent to the front by rail and truck the previous night) to the front on the night of 7/8 September, in taxicabs commandeered the previous evening. The division's attack failed completely so the taxicab troops had even less impact than sometimes supposed. Although “great publicity for Gallieni; militarily it was insignificant” in Herwig's view. Upon seeing the "taxicab army" ferrying troops to the front, Gallieni made one of the most oft-quoted remarks of the First World War: "Eh bien, voilà au moins qui n'est pas banal!" ("Well, here at least is something out of the ordinary!").[76][77][78]

Learning of Gallieni's contingency plans to evacuate Paris the previous day, Joffre telegraphed Millerand (8 September) demanding that he cancel Gallieni's “dangerous” message, and insisting that Gallieni was under his orders and had no business communicating directly with the government.[79] On 8 September Gallieni ordered Maunoury, under heavy pressure from von Kluck, to hold his ground. Joffre gave permission for Maunoury to pull back his left if necessary. The Germans, concerned at the gap between their First and Second Armies, began to pull back on 9 September, giving the Allies a strategic victory in the Battle of the Marne.[80]

After the Marne

When the German warships Goeben and Breslau went to Constantinople, Gallieni proposed attacking the Turkish straits.[81]

By early December 1914 some of Gallieni's supporters were suggesting that he be appointed Commander-in-Chief in Joffre's place, or be made Minister of War, or both.[82]

Gallieni was an early supporter of some kind of expeditionary force to the Balkans.[83] Early in 1915 Gallieni supported the proposal of Franchet d’Esperey and Aristide Briand (Justice Minister) for an expedition to Salonika, which he hoped would detach first Turkey then Austria-Hungary, leaving Germany “doomed.” President Poincare came out in favour of such a scheme, over Joffre's opposition, on 7 January 1915.[84]

Appointment

With Viviani’s government in trouble following the resignation of Delcasse as Foreign Minister, the unsuccessful autumn offensive and the entry of Bulgaria into the war, he asked Joffre, who had told him that nine out of ten generals would make poor ministers of war, whether Gallieni would be a good replacement for Millerand as Minister of War. Joffre replied “perhaps,” then after a pause for thought “maybe.” Although Gallieni agreed, in the event other French leaders refused to join Viviani's government so Briand formed a new government on 29 October 1915, with Viviani as Vice-President of the Council of Ministers (Deputy PM) and Gallieni as War Minister.[85]

Since July 1915 Joffre had been demanding that he be appointed commander-in-chief over all French forces, including those at the Dardanelles and Salonika. By November 1915 President Poincare was persuaded, and Briand, initially reluctant because of the difficulty of defending Gallieni's inclusion in his new ministry, agreed and on his first day in office asked Poincare to help him persuade Gallieni to accept Joffre's enhanced role. Gallieni agreed and wrote to Joffre—having first shown the letter to Briand—assuring him that “you can count on me.” Briand had the two men meet and shake hands.[86][87]

At the meeting of the Superior Council of Defence (24 November 1915) Joffre had Briand address the demarcation of his own and Gallieni's authority, and objected to the Council discussing operational matters, threatening to resign if they attempted to interfere with his “liberty.” Joffre met with Poincare and Briand both before and after the meeting to discuss the issue. Gallieni complained bitterly in his diary about the politicians’ unwillingness to stand up to Joffre. On 1 December Poincare and Briand met with Gallieni. They rejected the proposal prepared by his staff to vest authority in the Minister of War, Briand objecting that he would be obliged to answer questions in the Chamber about operational matters. Gallieni agreed that Joffre be commander-in-chief, with de Castelnau—who was soon sidelined—as his chief of staff, and under the War Minister's orders. A Presidential Decree of 2 December 1915 made Joffre “Commander-in-Chief of the French Armies” (generalissimo) over all theatres apart from North Africa. After considerable discussion this was approved by the Chamber of Deputies by 406-67 on 9 December.[88][89]

Policies

Gallieni cleared out soldiers from cushy jobs—three Paris theatres had been directed by Army officers. He authorised the renewed use of black African troops—50,000 in total—on the Western Front.[90] He introduced foyers du soldat—waiting rooms for soldiers in transit at railway stations.[91]

Although Gallieni supported the Salonika expedition, he shared Joffre's low opinion of Sarrail’s military abilities. On 12 November Gallieni ordered Sarrail to retreat to Salonika with as much of the Serb Army as he could gather. After Sarrail lobbied politicians for reinforcements Gallieni wrote back to 19 November telling him that he was not going to receive the four corps he wanted, although on 20 November he sent Sarrail (whom he thought “indecisive and not up to the task”) a telegram giving him a free choice as to whether to assist the latest Serb attack and when to fall back on Salonika.[92][93][94]

With evacuation of the Gallipoli bridgeheads under discussion, Gallieni was willing to divert troops there from Salonika for one last attempt.[95] On 9–11 December Gallieni took part in the Anglo-French talks in Paris (along with Grey (British Foreign Secretary), Kitchener (British War Secretary), Joffre and Briand) at which it was decided to maintain an Allied presence in Salonika, although it was unclear for how long. He later ordered Joffre to send an extra French division, although not the two Sarrail demanded.[96]

Resignation

Gallieni made an effort to unite soldiers and politicians, and to establish a working relationship in which he concentrated on supplying resources (not dissimilar to the role to which Kitchener was restricted in the UK from the end of 1915).[97] However, Gallieni had prostate cancer, with pain making him less tolerant of criticism at a time when political disquiet was growing after the failure of the Second Battle of Champagne, especially the failed attack on Hartmannswillerkopf and its subsequent total loss.[98][99]

In Clayton's view, Gallieni may well have been sceptical of Joffre's plans for a massive Anglo-French offensive on the Somme, to be accompanied by Italian and Russian offensives, as floated at the Chantilly meeting in 6–8 December 1915.[100] There was also friction over Gallieni's assertion of his right to appoint generals, Joffre's practice of communicating directly with the British generals rather than going through the War Ministry, and Gallieni's maintaining contacts with generals whom Joffre had replaced.[101]

In autumn 1915 Lt-Colonel Driant, a member of the Chamber of Deputies and commander of a chasseurs brigade, complained to Gallieni of how Joffre had been removing guns and garrisons from Verdun and even preparing some forts for demolition. Joffre was furious and disputed Gallieni's right to comment.[102][103] Driant, who had served at Verdun, was a member of the Army Commission of the Chamber of Deputies. The Council of Ministers discussed his reports and President Poincare asked Gallieni to investigate. Gallieni wrote to Joffre (16 or 18 December 1915) expressing concern at the state of trenches at Verdun and elsewhere on the front—in fact matters were already being taken in hand at Verdun.[104]

The political atmosphere was poisonous after the opening of the German attack at Verdun (21 February). Rumours circulated in Paris that Joffre had ordered the abandonment of Verdun at the end of February 1916 when the Germans first attacked. Gallieni demanded to see all paperwork from the period, but Joffre had made no such order in writing, merely despatching de Castelnau to assess the situation. Gallieni launched an angry report at the Council of Ministers on 7 March—read in his usual precise way—criticising Joffre's conduct of operations over the last eighteen months and demanding ministerial control, then resigned. Gallieni was falsely suspected of wanting to launch a military takeover of the government. Poincare wrote that Gallieni was trying to force Joffre's resignation, although it is unclear whether he was specifically trying to do so. Briand knew that publication of the report would damage morale and might bring down the government. Gallieni was persuaded to remain in office until a replacement had been designated and approved.[105][106]

Rocques was appointed as his successor after it had been ensured that Joffre had no objections.[107] This would be the last attempt to assert ministerial control over the army until Clemenceau became Prime Minister late in 1917.[108]

Later life

The strain of high office having broken his already fragile health, Joseph Gallieni died in May 1916.

Gallieni's Memoirs were published posthumously in 1920.[109]

He was posthumously made Marshal of France, in 1921. He was buried in Saint-Raphaël. Camp Gallieni in Kati was named after him.[110] There is also a Camp Galieni in Abidjan that serves as the Ivorian Arms forces Headquarters [111]

Assessments

Clayton describes him as a dry precise man, a secular republican (views which influenced his colonial policy) but one who kept aloof from politics.[112] Herwig describes him as “formidable” and “France’s most distinguished soldier” whose “physical appearance alone commanded respect”: he was of straight bearing and always wore full dress uniform.[113]

By the time Gallieni complained about Joffre's handling of Verdun, there was already public debate, much of it politically motivated, about which of them had “won” the First Battle of the Marne in 1914.[114] Churchill commends him for seeing the opportunity to outflank the German Army, using Manoury's Sixth Army, and for persuading the defeatist Joffre. "He is not thinking only of the local situation around Paris. He thinks for France and he behaves with the spontaneous confidence of genius in action.".[115] In his memoirs Gallieni claimed credit for that victory, and historians such as Georges Blond, Basil Liddell Hart, and Henri Isselin credited him with being the guiding intelligence, a claim disputed by Captain Lyet in his book “Joffre et Gallieni a la Marne” in 1938. Ian Senior describes "Gallieni's claims" as “absolute nonsense” and Lyet's book as “an excellent analysis which convincingly refutes" them.[116] Joffre himself once remarked: "Je ne sais pas qui l'a gagnée, mais je sais bien qui l'aurait perdue." (I do not know who won it [the battle], but I know well who would have lost it.").[117] Doughty writes of the Marne: “Gallieni’s role was important, but the key concept and decisions lay with Joffre”.[118]

Ethnology

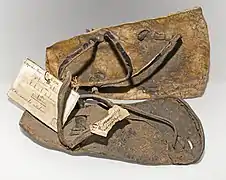

From the beginning of his colonial career he became interested in ethnology. He amassed a large collection of objects from French Sudan and Madagascar, which he donated to the Museum de Toulouse.

Shepherd Hat French Sudan MHNT

Shepherd Hat French Sudan MHNT Saber and its sheath French Sudan MHNT

Saber and its sheath French Sudan MHNT

Ankle bracelets. Culture Dan MHNT

Ankle bracelets. Culture Dan MHNT Pair of sandals (Sakalava people). It was exhibited at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 MHNT

Pair of sandals (Sakalava people). It was exhibited at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1900 MHNT

References

- "Gallieni, Joseph Simon | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- Basset, Charles (1903). Madagascar et l'oeuvre du Général Galliéni (in French). Paris: A. Rousseau.

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Herwig 2009, pp. 136–137

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Bernhard, Jacques (1991). Gallieni: le destin inachevé. Vagney: G. Louis. p. 16. ISBN 9782907016131.

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Herwig 2009, p. 226

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 339–340

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Finch, Michael P. M. (15 August 2013). A Progressive Occupation?: The Gallieni-Lyautey Method and Colonial Pacification in Tonkin and Madagascar, 1885-1900. OUP Oxford. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-166209-6.

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Herwig 2009, pp. 136–137

- Roland, Oliver; Fage, John; Sanderson, G.N. (1985). The Cambridge History of Africa 6. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22803-9.

- Aldrich 1996, p. 63

- Thomas Rid (2010). "The Nineteenth Century Origins of Counterinsurgency Doctrine". Journal of Strategic Studies. Journal of Strategic Studies, 33(5): 727–758. 33 (5): 727–758. doi:10.1080/01402390.2010.498259. S2CID 154508657.

- Aldrich 1996, p. 106

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Aldrich 1996, p. 214

- Herwig 2009, pp. 136–137

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Doughty 2005, pp. 10, 14

- Herwig 2009, pp. 136–137

- Tuchman 1962, p. 48

- Doughty 2005, pp. 14–15

- Doughty 2005, p. 41

- Tuchman 1962, p. 181

- Clayton 2003, 38

- Tuchman 1962, p. 261

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- "Joseph-Simon Gallieni | Colonial administrator, Governor of Madagascar | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 23 May 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- Tuchman 1962, p. 181

- Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 339–340

- Tuchman 1962, p. 340

- Herwig 2009, pp. 136-137

- Doughty 2005, p. 82

- Tuchman 1962, p. 184 literally: "he has always made me froth"

- Tuchman 1962, p. 233

- Clayton 2003, p. 47

- Doughty 2005, pp. 82–84

- Clayton 2003, pp. 53–57

- Tuchman 1962, p. 399

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 364-365

- Greenhalgh 2014, pp. 44–46

- Greenhalgh 2014, pp. 44–46

- Paris had been besieged and eventually taken by the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 392–394, 397

- Clayton 2003, pp. 537

- Doughty 2005, p. 85

- Herwig 2009, pp. 226–227

- Tuchman 1962, p. 399

- Clayton 2003, pp. 53–57

- Clayton 2003, pp. 53–57

- Tuchman 1962, p. 397

- Herwig 2009, pp. 226–227

- Doughty 2005, p. 87

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 408–409

- Doughty 2005, pp. 86–89

- Herwig 2009, p. 227

- Herwig 2009, p. 228

- Doughty 2005, pp. 87–89

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 411–412

- Senior 2012, p. 188

- Tuchman 1962, pp. 416–417

- Herwig 2009, p. 229

- Doughty 2005, pp. 87–90

- Senior 2012, pp. 190–191

- Tuchman 1962, p. 419

- Herwig 2009, p. 254

- Doughty 2005, p. 111

- Herwig 2009, p. 253

- Clayton 2003, pp. 53–57

- Senior 2012, pp. 253–254, 375

- Herwig 2009, pp. 248, 262

- Herwig 2009, p. 254

- Herwig 2009, p. 263

- Tuchman 1962, p. 161

- Doughty 2005, p. 151

- Doughty 2005, p. 204

- Palmer 1998, p. 29

- Doughty 2005, pp. 226–229

- Doughty’s account is sourced to Gallieni’s carnets — the wording implies, without explicitly saying so, that he had already sent the letter to Joffre by the time he showed it to Poincare.

- Doughty 2005, pp. 229–231

- Doughty 2005, pp. 231–232

- Clayton 2003, pp. 82–83

- Clayton 2003, pp. 82–83

- Clayton 2003, p. 88

- Doughty 2005, pp. 226–227, 232

- Doughty 2005, p. 232

- Clayton 2003, pp. 82–83

- Palmer 1998, p. 47

- Doughty 2005, pp. 236–237

- Clayton 2003, p. 88

- Clayton 2003, pp. 97–98

- Doughty 2005, pp. 284–285

- Clayton 2003, pp. 82–83

- Clayton 2003, pp. 97–98

- Sumner 2014, p. 97

- Clayton 2003, pp. 97–99

- Doughty 2005, pp. 264, 266

- Clayton 2003, pp. 97–98

- Doughty 2005, pp. 272, 284–285

- Doughty 2005, p. 285

- Clayton 2003, pp. 97–98

- Senior 2012, p. 381

- Mann, Gregory (April 2005). "Locating Colonial Histories: Between France and West Africa". The American Historical Review. 110 (5): 409–434. doi:10.1086/531320. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013.

- https://www.defense.gouv.ci/presse/details_agenda/crmonie-dhommage-lancien-ministre-detat-ministre-de-la-dfense-konan-koffi-leon-letat-major-gnral-des-armes-au-camp-gallieni-au-plateau.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Clayton 2003, pp. 215–216

- Herwig 2009, pp. 136–137

- Greenhalgh 2014, pp. 131–132

- Churchill, Winston. 1923. The World Crisis

- Senior 2012, p. 379

- André Adamlien (1966). Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée 1(1): 254–258.

- Doughty 2005, p. 97

Notes

- Marshal of France is a dignity and not a rank.

Further reading

- Cassar, George H. (2011). Lloyd George at War, 1916-18. Anthem Press, London. ISBN 978-0-857-28392-4.

- Clayton, Anthony (2003). Paths of Glory. Cassell, London. ISBN 0-304-35949-1.

- Doughty, Robert A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02726-8.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2005). Victory Through Coalition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09629-4.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1994). The World War One Sourcebook. Arms and Armour Press, London. ISBN 1-85409-102-6

- Herwig, Holger (2009). The Marne. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-7829-2.

- Palmer, Alan (1998). Victory 1918. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84124-6.

- Prete, Roy (2009). Strategy And Command, 1914. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-3522-0.

- Sumner, Ian (2012). They Shall Not Pass: The French Army on the Western Front 1914-1918. Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-848-84209-0.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1962). August 1914. Constable & Co. ISBN 978-0-333-30516-4.

External links

- Newsreel of the British Pathé: Gallieni visits a hospital (c. 1914)

- Newspaper clippings about Joseph Gallieni in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW