Gamaliel

Gamaliel the Elder (/ɡəˈmeɪliəl, -ˈmɑː-, ˌɡæməˈliːəl/;[1] also spelled Gamliel; Hebrew: רַבַּן גַּמְלִיאֵל הַזָּקֵן Rabban Gamlīʾēl hazZāqēn; Koinē Greek: Γαμαλιὴλ ὁ Πρεσβύτερος Gamaliēl ho Presbýteros), or Rabban Gamaliel I, was a leading authority in the Sanhedrin in the early first century CE. He was the son of Simeon ben Hillel and grandson of the great Jewish teacher Hillel the Elder. He fathered Simeon ben Gamliel, who was named for Gamaliel's father,[2] and a daughter, who married a priest named Simon ben Nathanael.[3]

| Rabbinical eras |

|---|

In the Christian tradition, Gamaliel is recognized as a Pharisee doctor of Jewish Law.[4] Acts of the Apostles, 5 speaks of Gamaliel as a man held in great esteem by all Jews and as the Jewish law teacher of Paul the Apostle in Acts 22:3.[5] Gamaliel encouraged his fellow Pharisees to show leniency to the apostles of Jesus Christ in Acts 5:34.[6]

In Jewish tradition

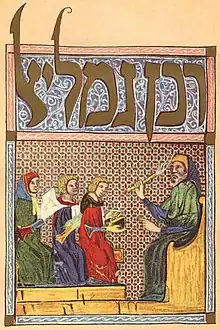

(רבן גמליﭏ)

In the Talmud, Gamaliel is described as bearing the titles Nasi (Hebrew: נָשִׂיא Nāśīʾ) "prince" and Rabban "our master", as the president of the Great Sanhedrin in Jerusalem; although some dispute this, it is not doubted that he held a senior position in the highest court in Jerusalem.[2] Gamaliel holds a reputation in the Mishnah for being one of the greatest teachers in all the annals of Judaism: "Since Rabban Gamaliel the Elder died, there has been no more reverence for the law, and purity and piety died out at the same time".[7]

Gamaliel's authority on questions of religious law is suggested by two Mishnaic anecdotes in which "the king and queen" ask for his advice about rituals.[8] The identity of the king and queen in question is not given, but is generally thought to either be Herod Agrippa and his wife Cypros the Nabataean, or Herod Agrippa II and his sister Berenice.[2][9]

As rabbinic literature always contrasts the school of Hillel the Elder to that of Shammai and only presents the collective opinions of each of these opposing schools of thought without mentioning the individual nuances and opinions of the rabbis within them, these texts do not portray Gamaliel as being knowledgeable about the Jewish scriptures, nor do they portray him as a teacher.[2] For this reason, Gamaliel is not listed as part of the chain of individuals who perpetuated the Mishnaic tradition.[10] Instead the chain is listed as passing directly from Hillel to Yohanan ben Zakkai.

Nevertheless, the Mishnah mentions Gamaliel's authorship of a few laws about community welfare and conjugal rights. He argued that the law should protect women during divorce, and that, for the purpose of remarriage, a single witness was sufficient evidence for the death of a husband.[11]

Various pieces of classical rabbinic literature additionally mention that Gamaliel sent out three epistles, designed as notifications of new religious rulings, and which portray Gamaliel as the head of the Jewish body for religious law.[12] Two of these three were sent, respectively, to the inhabitants of Galilee and "the Darom" (southern Judea), and were on the subject of the first tithe. The third epistle was sent to the Jews of the diaspora and argued for the introduction of an intercalary month.

_Chapelle_Saint-Nicod%C3%A8me_Retable_de_la_Descente_de_Croix_20.JPG.webp)

Since the Hillel school of thought is presented collectively, there are very few other teachings which are clearly identifiable as Gamaliel's. There is only a cryptic dictum, comparing his students to classes of fish:

- A ritually impure fish: one who has memorized everything by study, but has no understanding, and is the son of poor parents

- A ritually pure fish: one who has learnt and understood everything, and is the son of rich parents

- A fish from the Jordan River: one who has learnt everything, but doesn't know how to respond

- A fish from the Mediterranean Sea: one who has learnt everything, and knows how to respond

In some manuscripts of Dunash ibn Tamim's tenth-century Hebrew commentary on the Sefer Yetzirah, the author identifies Gamaliel with the physician Galen. He claims to have seen an Arabic medical work translated from Hebrew entitled The Book of Gamaliel the Prince (Nasi), called Galenos among the Greeks.[13] However, since Galen lived in the second century and Gamaliel died during the mid-first century, this is unlikely.

Quotes

In the Pirkei Avot, Gamaliel is credited as saying:

Make a teacher for yourself and remove yourself from doubt; and do not give excess tithes by estimating.[14][15]

In Christian tradition

The Acts of the Apostles introduces Gamaliel as a Pharisee and celebrated doctor of the Mosaic Law in Acts 5:34–40. In the larger context (vs.17–42), Peter and the other apostles are described as being prosecuted before the Sanhedrin for continuing to preach the gospel despite the Jewish authorities having previously prohibited it. The passage describes Gamaliel as presenting an argument against killing the apostles, reminding them about the previous revolts of Theudas and Judas of Galilee, which had collapsed quickly after the deaths of those individuals. Gamaliel's advice was accepted after his concluding argument:

And now I say unto you, Refrain from these men, and let them alone: for if this counsel or this work be of men, it will come to nought: But if it be of God, ye cannot overthrow it; lest haply ye be found even to fight against God.

The Book of Acts later goes on to describe Paul the Apostle recounting that although "born in Tarsus", he was brought up in Jerusalem "at the feet of Gamaliel, [and] taught according to the perfect manner of the law of the fathers" (Acts 22:3). No details are given about which teachings Paul adopted from Gamaliel, as it is assumed that as a Pharisee, Paul was already recognized in the community at that time as a devout Jew. Also, how much Gamaliel influenced aspects of Christianity is unmentioned. However, there is no other record of Gamaliel ever having taught in public,[2] but the Talmud does describe Gamaliel as teaching a student who displayed "impudence in learning", which a few scholars identify as a possible reference to Paul.[16] The relationship of Paul the Apostle and Judaism continues to be the subject of scholarly debate. Helmut Koester, Professor of Divinity and of Ecclesiastical History at Harvard University, questions if Paul studied under this famous rabbi, arguing that there is a marked contrast in the tolerance that Gamaliel is said to have expressed about Christianity with the "murderous rage" against Christians that Paul is described as having prior to his conversion (Acts 8:1–3).

Alleged Gospel of Gamaliel

The "Gospel of Gamaliel" is a hypothetical book speculated to exist by some scholars, perhaps a part of Pilate apocrypha. While no ancient sources directly refer to such a gospel, Paulin Ladeuze and Carl Anton Baumstark first proposed that such a book existed in 1906. Scholars who believe such a book once existed have reconstructed it from a homily, the "Lament of Mary" (Laha Maryam) by a bishop named Cyriacus. They believe Laha Maryam extensively quotes the Gospel of Gamaliel; the Lament includes a section that leads with "I, Gamaliel" which caused the speculation that these sections were actually quoting an existing gospel. Other scholars believe that such inference that the author was "plagiarizing" a lost gospel is unwarranted, and these sections are simply written by Cyriacus from the perspective of Gamaliel.[17]

Reasonably complete manuscripts of Laha Maryam exist in both Ethiopian (Ge'ez) and Karshuni (Arabic) language versions. Regardless of whether Laha Maryam is quoting a lost gospel or not, Gamaliel does feature in it. He is a witness to a miracle of healing in the raising of a dead man at Jesus's tomb; Jesus's abandoned grave-cloths have miraculous powers. Gamaliel also talks with Pontius Pilate, who is portrayed highly positively as a Christian himself.[18]

Veneration

Ecclesiastical tradition claims that Gamaliel had embraced the Christian faith and his tolerant attitude toward early Christians is explained by this. According to Photios I of Constantinople, he was baptised by Saint Peter and John the Apostle, together with his son Abibon (Abibo, Abibas, Abibus) and Nicodemus.[19] The Clementine Literature suggested that he maintained secrecy about the conversion and continued to be a member of the Sanhedrin for the purpose of covertly assisting his fellow Christians.[20] Some scholars consider the traditions to be spurious,[21] and the passage in which Gamaliel is mentioned does not state that he became a Christian either implicitly or explicitly.

The Eastern Orthodox Church venerates Gamaliel as a saint, and he is commemorated on August 2,[22][23] the date when tradition holds that his relics were found, along with those of Stephen the Protomartyr, Abibon (Gamaliel's son), and Nicodemus. The traditional liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church celebrates the same feast day of the finding of the relics on August 3. It is said that in the fifth century, by a miracle, his body had been discovered and taken to Pisa Cathedral.[24]

Gamaliel is referred to in the 15th-century Catalan document, Acts of Llàtzer.[25]

See also

References

- Jones, Daniel; Gimson, A.C. (1977). Everyman's English Pronouncing Dictionary. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 207.

- Schechter, Solomon; Bacher, Wilhelm. "Gamliel I". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Avodah Zarah 3:10

- "Gamaliel". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, L. Scott; Quarles, Charles (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. B & H Publishing Group. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3.

- Raymond E. Brown, A Once-and-Coming Spirit at Pentecost, page 35 (Liturgical Press, 1994). ISBN 0-8146-2154-6

- Sotah 9:15

- Pesahim 88:2

- Adolph Buechler, Das Synhedrion in Jerusalem, p.129. Vienna, 1902.

- Pirkei Abot 1–2

- Yevamot 16:7

- Tosefta Sanhedrin 2:6; Sanhedrin 11b; Jerusalem Talmud Sanhedrin 18d; Jerusalem Talmud Ma'aser Sheni 56c

- Gero, Stephen (1990). "Galen on the Christians: A Reappraisal of the Arabic Evidence". Orientalia Christiana Periodica. 56 (2): 393.

- Six Orders of the Mishnah (Pirḳe Avot 1:16).

- The Living Talmud - The Wisdom of the Fathers, ed. Judah Goldin, New American Library of World Literature: New York 1957, p. 72

- Shabbat 30b

- Suciu, Alin (2012). "A British Library Fragment from a Homily on the Lament of Mary and the So-Called Gospel of Gamaliel". Aethiopica. 15: 53–71. doi:10.15460/aethiopica.15.1.659. ISSN 2194-4024.

- Günter Stemberger, Jews and Christians in The Holy Land: Palestine in The Fourth Century, pages 110–111 (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 2000. ISBN 0-567-08699-2); citing M.-A. van den Oudenrijn, Gamaliel: Athiopische Texte zur Pilatusliteratur (Freiburg, 1959).

- Paton James Gloag, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on The Acts of the Apostles, Volume 1, page 191, citing Photius, Cod. 171 (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1870).

- Recognitions of Clement 1:65–66

- Geoffrey W. Bromiley (editor), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Volume Two, E–J, page 394 (Wm B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1915; Fully Revised edition, 1982). ISBN 0-8028-3782-4

- Russian Orthodox Christian Menaion Calendar (referenced Aug 14, 2020)

- Saint Gamaliel (referenced August 14, 2020)

- "Gamaliel the Elder", Catholic Encyclopedia

- Diccionari de la Literatura Catalana (2008)

External links

![]() Media related to Gamaliel at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gamaliel at Wikimedia Commons

- The Jewish Encyclopedia on Gamaliel I

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 434.

- Perspectives on Transformational Leadership in the Sanhedrin of Ancient Judaism