Garibaldi, Oregon

Garibaldi (/ˌɡærɪˈbɔːldi/ GARR-ib-AWL-dee) is a city in Tillamook County, in the U.S. state of Oregon. The population was 830 at the 2020 census.

Garibaldi, Oregon | |

|---|---|

Garibaldi and Tillamook Bay | |

| Motto: "Oregon's Authentic Fishing Village" | |

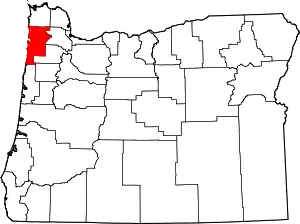

Location in Oregon | |

| Coordinates: 45°33′37″N 123°54′41″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| County | Tillamook |

| Incorporated | 1946 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor pro tem | Kathryn "Katie" Findling (2023) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.37 sq mi (3.54 km2) |

| • Land | 0.99 sq mi (2.55 km2) |

| • Water | 0.38 sq mi (0.99 km2) |

| Elevation | 22 ft (6.7 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 830 |

| • Density | 841.78/sq mi (324.87/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (Pacific) |

| ZIP code | 97118 |

| Area code | 503 |

| FIPS code | 41-28000[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1121062[4] |

| Website | www.ci.garibaldi.or.us |

History

The indigenous Tillamook people have lived along the Oregon coast –including the Tillamook Bay– for about 12,000 years;[5] from Tillamook Head in the North, to Cape Foulweather in the south, and extending inland to the summit of the Oregon Coast Range.[6] They lived in permanent cedar-plank lodges, illuminated at night with torches or by burning fish heads or whale oil. Their diet included salmon, mussels, lampreys, berries, wild mustard, camas, grouse, beaver, deer, and elk.[5]

Captain Robert Gray, born in Rhode Island and sailing from Boston, sailed the Lady Washington into Tillamook Bay in 1788, where his crew fought with the Tillamook people.[7] The Lewis and Clark expedition recorded in 1806 that 2,400 Tillamook people resided on Oregon's coast.[8] As the white settler population increased, indigenous people suffered from newly introduced diseases including smallpox. By 1930 only 22 indigenous people remained in all of Tillamook County.[8]

Daniel Bayley was the first white property owner on this part of Tillamook Bay, having first settled here after the Civil War. Bayley was one of the first white settlers who arrived in Tillamook Bay's northern end area.[9] Bayley built a hotel and general store on what is now known as Bay Lane. In 1867, Bayley subdivided the Bayley Park Addition and was officially granted title to the property on May 15, 1869, by President Ulysses S. Grant. In 1870, he was appointed by President Grant as the area's first postmaster and given the duty of naming the postmark. This same year, Giuseppe Garibaldi helped unify Italy after a military career devoted to establishing democracy around the world and Bayley felt so inclined to name the post office after his hero.[10]

Starting in the 1870s, the region's indigenous people were relocated to the nearby Hobsonville Indian Community. By the 1930s, this community was composed mostly of elderly women and children, and given the nickname "Squawtown". Tourists and antiquities dealers would visit, and the local Ku Klux Klan occasionally harassed the residents. The community was abandoned by WWII, and some residents moved to Garibaldi.[7]

Garibaldi's first school (Hobson School) was built in 1896. In 1907 the school was moved close to where it now stands between Cypress and Driftwood under the big "G". In 1926, the new high school opened so Garibaldi students no longer had to attend secondary school in Bay City. In 1954, north Tillamook County high schools were consolidated as Neah-Kah-Nie High School north of Rockaway Beach. Garibaldi High School became a grade school.

The Whitney mill was opened in 1921. The tall smokestack, today all that remains, was constructed by the Hammond Company in 1927–28.

Garibaldi was incorporated as a City in 1946.[9] During the 1950s the city's population increased to over 1500 with the construction of two large mills, The Oceanside Lumber Company and Oregon-Washington Plywood Corporation. The Oregon-Washington Mill closed in the late 1970s.[11] Weyerhaeuser hardwood mill at the Port of Garibaldi was acquired in 2011 by a New York-based company and has been operating as Northwest Hardwoods, Inc. since the acquisition.[12]

In 2020, writer Helen Hill suggested removing Garibaldi's statue of Captain Robert Gray, due to claims about his treatment of indigenous people. The statue, which stands outside the Garibaldi Maritime Museum, depicts Gray standing on a sacred box with Haida designs. As of 2020, the museum's board will consider adding information next to the statue.[13]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.37 square miles (3.55 km2), of which, 0.99 square miles (2.56 km2) is land and 0.38 square miles (0.98 km2) is water.[14]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 213 | — | |

| 1950 | 1,249 | — | |

| 1960 | 1,163 | −6.9% | |

| 1970 | 1,083 | −6.9% | |

| 1980 | 999 | −7.8% | |

| 1990 | 877 | −12.2% | |

| 2000 | 899 | 2.5% | |

| 2010 | 779 | −13.3% | |

| 2020 | 830 | 6.5% | |

| 1930 population[15] U.S. Decennial Census[16][2] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[17] of 2010, there were 779 people, 384 households, and 222 families living in the city. The population density was 786.9 inhabitants per square mile (303.8/km2). There were 524 housing units at an average density of 529.3 per square mile (204.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.7% White, 0.1% African American, 0.8% Native American, 0.9% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 3.3% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.5% of the population.

There were 384 households, of which 15.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.4% were married couples living together, 8.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 2.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 42.2% were non-families. 33.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.99 and the average family size was 2.45.

The median age in the city was 55.1 years. 12.5% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.1% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 13% were from 25 to 44; 41.4% were from 45 to 64; and 28.1% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 50.6% male and 49.4% female.

2000 census

As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 899 people, 436 households, and 251 families living in the city. The population density was 928.4 inhabitants per square mile (358.5/km2). There were 584 housing units at an average density of 603.1 per square mile (232.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.77% White, 1.78% Native American, 0.67% Asian, 0.11% Pacific Islander, 0.22% from other races, and 2.45% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.33% of the population.

There were 436 households, out of which 16.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.5% were married couples living together, 6.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 42.4% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 17.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.04 and the average family size was 2.55.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 16.2% under the age of 18, 6.1% from 18 to 24, 21.4% from 25 to 44, 31.3% from 45 to 64, and 25.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 49 years. For every 100 females, there were 99.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 103.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,945, and the median income for a family was $37,266. Males had a median income of $30,938 versus $23,359 for females. The per capita income for the city was $18,075. About 6.9% of families and 11.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.5% of those under age 18 and 7.4% of those age 65 or over.

Historical population

The population was 200 in 1915.[9]

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Tillamook". www.oregonencyclopedia.org. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- "Indians 101: The Tillamook Indians". Daily Kos. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- "Hobsonville Indian Community". www.oregonencyclopedia.org. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- "Tillamook". www.oregonencyclopedia.org. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- Engeman, Richard H. (September 1, 2009). The Oregon Companion: An Historical Gazetteer of the Useful, the Curious, and the Arcane. Timber Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-60469-147-4.

- McArthur, Lewis A.; McArthur, Lewis L. (2003). Oregon Geographic Names (Seventh ed.). OHS Press. p. 392. ISBN 0875952771. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- "ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR THE PORT OF GARIBALDI WHARF REDEVELOPMENT PROJECT,TILLAMOOK COUNTY, OREGON" (PDF). Port of Garibaldi. Archaeological Investigations Northwest, Inc. September 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- Herald, LeeAnn Neal For the Headlight. "Garibaldi sawmill part of sale to New York company". Tillamook. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- "Call to remove statue of explorer who brutalized Native Americans ignites firestorm in Tillamook County". news.streetroots.org. Retrieved September 16, 2021.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "Oregon Secretary of State: Seaside to Bay City". Oregon. 1940. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- "Garibaldi city, Oregon Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 21, 2012.