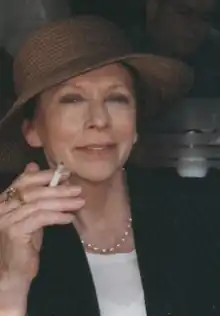

Gatja Helgart Rothe

Gatja Helgart Rothe (also known as G.H. Rothe; (née Helgart Riedel) (March 15, 1935 – August 3, 2007), was a German-American artist known for her printmaking, especially mezzotint. She was also a draftswoman and painter. After living and working in Europe, she briefly traveled through South America before moving to New York City in the 1970s and later, California. Her commercial success was primarily based on mezzotints and paintings commissioned and handled by galleries, dealers, and private collectors in the United States, Europe and Japan.

Gatja Helgart Rothe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Helgart Riedel March 15, 1935 Beuthen |

| Died | August 3, 2007 |

Early life

Helgart Riedel was born in 1935 to Elizabeth and Harry Riedel in Beuthen, in German Silesia, which was ceded to Poland at the end of World War II. During the War her father served in the German army, while her mother left Beuthen with Riedel and her four brothers trying to find a way into West Germany. After more than a year of constant movement they finally settled in Wiedenbrück in 1947. These early years as a war refugee would have a profound impact on her artwork.

Her father, who survived the war, was able to join the family in Wiedenbrück, where he reestablished his jewelry trade, building a goldsmith studio at their house and opening a jewelry store in town. Riedel became an apprentice in her father’s workshop. Assigned the task of drawing one flower every day, she began to develop her artistic skills and passion.

Southern Germany and Italy

In 1956, at age twenty-one, Riedel hitchhiked to southern Germany, where her brother was studying design at the art academy in Pforzheim. She enrolled in painting and drawing classes there and met her future husband, Curt Rothe, a painting professor and post-impressionist artist.[1][2][3]

Riedel became increasingly interested in this bohemian counterculture and in the estate’s atmosphere of freedom. In 1958 Riedel married Rothe, with an agreement that she could continue to pursue her career as an artist. Their son Peter was born in 1959. While caring for her child and the estate, she developed a body of work that explored the intimacies of bodies and what she called “anatomy landscapes.” She received her first solo show in 1967, exhibiting paintings of eccentric humanoid forms depicted inside boxes.

In 1968 she was awarded the Villa Romana Prize for emerging German artists and traveled with her son to Florence. For the next year, she was provided with all the materials she needed, allowing her to develop her technique and artistic language, as well as her professional independence.

Travels to South America

During her stay in Florence, Rothe had a series of shows in Spain facilitated by a gallery owner and curator who eventually became her lover. They traveled from Barcelona to Montevideo on a cruise ship, leaving Rothe's son with his father at the estate in southern Germany. The couple then traveled in a van around South America for nine months, but Rothe’s lover fell ill and had to go back to Europe for treatment for his alcoholism.

New York City

Rothe left Montevideo in 1971, following advice of an artist friend who suggested she move to New York City. Rothe began painting landscapes and skylines, and kept exploring her interest in bodies. In her early paintings in New York she began her explorations with layering, creating compositional narratives out of her experiences in the city. She started attending the ballet and expanded her interest in the body into studies of dancers in movement.

A gallery owner and friend suggested that, if she wanted to earn a living from her artwork, it might be more efficient to create prints than paintings. As she delved into different printmaking techniques, Rothe became intrigued by mezzotint, which, while requiring a high level of skill and patience working by hand directly on the copper, permits the nuance of every line and detail to be seen. Combining the knowledge from her studies in anatomy, art history, goldsmithing, and drawing, she arrived at an original process that allowed her to achieve detailed transparencies with mezzotint. Another innovation was a method of applying and hand-wiping all colors on the same plate. Her first mezzotints with transparencies were completed in 1972 and soon garnered a lot of attention.

A good friend in New York gave her the name Gatja, which she adopted in signing most of her work. Believing that people might taker her more seriously if they assumed she was a man, she then decided to use the initials G. H. and her last name.

In 1973 her husband died and her son Peter moved in with her. At the time she was designing jewelry for Tiffany’s and other jewelers.[4] In 1976 Rothe signed a contract with Hammer Galleries in New York.[5] She worked in a studio at 193 Second Avenue in Lower Manhattan. In 1978 she was listed in both Who’s Who in American Art and Who’s Who in America.[4]

California and the Peak of Rothe’s Artistic Career (1978–2000)

In 1978 Rothe traveled to Los Angeles to visit her lover Maurie Symonds,[6] who owned several galleries in California showing her work. Rothe became fascinated with Carmel-by-the-Sea, California and decided to move there, buying a house by in Carmel-by-the-Sea, although she kept a storage space and a studio in New York.

The open and rural California landscapes influenced her new mezzotints, in which she included mountains, horses and other scenes. In 1982 her son Peter bought her contract from Hammer Galleries, which no longer wanted to carry prints. The scandal caused by Salvador Dalí’s pre-signed papers had adversely affected the entire graphics industry, devaluing the worth of copies in editions.[7] Rothe survived this issue because not only did she limit her editions to 150, but also each print was unique, since she mixed all the colors on the plate by hand. Peter became the mediator between Rothe and the art market, giving her the space to further develop her technique.

Throughout most of the 1980s and 90s, Rothe had about ten large shows each year in different US cities, and Peter regularly showed her work at the Basel Art Fair. Every month or two, she created a new edition for galleries to buy. She made all of her work with the help of one assistant. Rothe also did paintings for private commissions, but she rarely kept track of these sales. Sylvester Stallone and Clint Eastwood, who were her neighbors in Carmel, both own some of her paintings. She painted a large outdoor mural in the Hog’s Breath Inn, Clint Eastwood’s former restaurant in Carmel.

In 1987 Peter sold Rothe's art business to Paul Zueger from American Design. A year after in 1986, her brother opened Riedel Art Gallery to represent her work in Germany, and Rothe moved her New York studio from Manhattan to Brooklyn in order to have more space. She began exploring large pastel paintings and creating frescoes at her own home. Later, after a drawn-out lawsuit with Zueger, Rothe finalized her contract with them and opened her own gallery in Carmel in 1991. In 1988 and 1992 she was nominated to represent the United States as an artist at the Olympic Games in Seoul and Barcelona.

Later years and death

In 2000, after some tiresome lawsuits had finally been settled, Rothe decided to move to Geneva, Switzerland, fulfilling a desire to return to Europe. Here, she lived off the sale of her house in Carmel. In Geneva Rothe painted mountain landscapes, massive horse paintings, portraits, and other scenes inspired by her surroundings. In 2003 Rothe was diagnosed with breast cancer, but it was a heart problem that led to her death on August 3, 2007.

Work

Early drawings

During her early artistic work at the Pforzheim Academy, Rothe completed a series of small, highly detailed monotypes, etchings, and drawings. These works, which she sometimes referred to as “body landscapes,” explored her own sexuality, representing nude bodies from different angles and perspectives. Her depictions of nudes in strange positions were sometimes accompanied by surreal imagery of isolated body parts such as eyes or muscles.

Mezzotints

Rothe's highly detailed mezzotints focused on surreal landscapes, intricately rendered horses, and graceful dancers. Rothe started all her prints by sketching a simple drawing directly onto the plate with a drypoint tool. She used a rocker to develop the background, rolling and rocking it side to side and piercing the plate with tiny holes for the ink. Using a drypoint tool she further developed the fine details and figures of the drawing. Rothe spent approximately 500 hours working on each plate.[8]

Rothe expanded the technique's possibilities to achieve transparencies and an extensive variety of tonalities. By discovering a way to mix all colors in the same plate, from the darkest to the lightest, and hand-wiping them into one another, she was able to create highlights, hues, and tones impossible to get when inking each color separately.

Paintings

Rothe did not keep track of most of the paintings she sold, but the ones that are known show her interest in transparencies. Through allowing layers of paint to dry and using different types of strokes to achieve slight shifts in tones and hues, most of her city and nature landscapes, as well as portraits, display an intricate layering.[9]

"Gerotica"

Completed in 1987 but never shown during her lifetime, Rothe’s tempera works are depictions of sex and intimacy between aging couples, revealing Rothe's typical layering of paint. Rothe’s son Peter discovered these erotic scenes with geriatric bodies (“gerotica”) paintings and other artworks years after her death. In November 2015 the gerotica became the center for the exhibition Seven Drawings at the Walter and McBean Galleries of the San Francisco Art Institute.[10][11][12][13]

Graffiti doors

Rothe was interested in the graffiti on boarded-up windows and doors she saw in New York City while she lived there in the 1970s and during her visits to her studio in Manhattan and later in Brooklyn. She sometimes negotiated with the owners to take the boards and replace them with new ones. She then intervened on these boards with painting and gold leaf. Most of these pieces went unsold. She shipped the graffiti works to Carmel for an exhibition, and eventually they were sent to Germany for an exhibition at the Riedel Art Gallery, where they have remained.

References

- "Curt Rothe "Martwa Natura" Galeria Żak".

- "Curt Rothe Auction Results - Curt Rothe on artnet".

- "Curt Rothe Works on Sale at Auction & Biography - Invaluable".

- Riedel-Zapp, Petra. "About G.H.ROTHE (English) - Riedel Art Gallery (Düsseldorf, Ratingen-Hösel)".

- exhibit-e.com. "Hammer Galleries". www.hammergalleries.com. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- "Revolutionary in the name of art - Obituaries - smh.com.au". 5 January 2007.

- "DALI TRYING TO REPAIR BUSINESS AFFAIRS AND RESOLVE ART SCANDALS". The New York Times. 26 March 1981.

- ptenso (2 December 2014). "G H Rothe 1986 documentary" – via YouTube.

- "Artwork".

- "G.H. Rothe: Seven Paintings - SFAI".

- "G.H. Rothe - Reviews - Art in America".

- "Juxtapoz Magazine - G.H. Rothe: Seven Paintings @ SFAI".

- "S.F. exhibits showcase unseen work of Leslie Shows, G.H. Rothe". 8 December 2015.

Sources

- The Creative Woman. Governors State University. 1986-01-01.

- Smith, Donald E. (2004-01-01). American Printmakers of the Twentieth Century: A Bibliography. Donald E. Smith. ISBN 9781878282286.