Gazi Husrev Bey

Gazi Husrev-beg (Ottoman Turkish: غازى خسرو بك, Gāzī Ḫusrev Beğ; Modern Turkish: Gazi Hüsrev Bey; 1480–1541) was an Ottoman Bosnian sanjak-bey (governor) of the Sanjak of Bosnia in 1521–1525, 1526–1534, and 1536–1541. He was known for his successful conquests and campaigns to further Ottoman expansion into Croatia and Hungary. However, his most important legacy was major contribution to the improvement of the structural development of Sarajevo and its urban area. He ordered and financed construction of many important buildings there, and with his will bequeathed all his wealth into endowment for the construction and long-term support of religious and educational facilities and institutions, such as the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, and the Gazi Husrev-begova Medresa complex with a Gazi Husrev-beg Library, also known as Kuršumlija.

Gazi Husrev-beg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Ḫusrev |

| Born | 1480 Serres, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Greece) |

| Died | 1541 Mokro, Ottoman Empire (modern-day Montenegro) |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | –1541 |

| Rank | Sanjak-bey of Bosnia and Smederevo |

| Battles/wars |

|

Biography

Origin

Gazi Husrev-beg was born in Serres, Greece.[1] His father, Ferhad-beg, was a Bosnian nobleman from Hum (modern-day Herzegovina), who worked as a high court official.[2] His mother, Selçuk Sultan, was the daughter of the Sultan Bayezid II, making Gazi Husrev-beg Beyazid II's grandson.

Career

In less than three years, he conquered the fortresses of Knin, Skradin and Ostrovica. He was appointed sanjak-bey of the Sanjak of Bosnia on 15 September 1521, becoming one of Sultan Suleiman I's most trusted men.

A relentless campaign of conquest followed soon; the fortified towns of Greben, Sokol, Jezero, Vinac, Vrbaški Grad, Livač, Kamatin, Bočac, Udbina, Vrana, Modruč, and Požega fell at his hands.

He founded, among the many buildings he ordered to construct in the city, the vakuf of Sarajevo, which was active until the 20th century.[3]

Gazi Husrev-beg played a crucial role to overcome the Christian army at the Battle of Mohács. His 10,000 Akıncıs and his irregular cavalry, composed of Turks, Bosnians and Crimean Tatars, served as reserve soldiers in that battle. According to the Ottoman military strategy, the Akıncıs circled the European knights while the Turkish infantry made a counterfeit retreat after the first assault.

Death

Gazi Husrev-beg's forces struggled against a power vacuum in Montenegro after the death of Ottoman ally, islamized Montenegrin lord Skender-beg Crnojević in 1528. In 1541, during an uprising of Montenegro nobility, he set out to protect the Crnojevićs and the local populace. After fighting many battles to maintain order in the region, although finally victorious, he was killed while fighting Christian rebels in Mokro, a small village in Drobnjaci (present-day Montenegro). Legend states that he was a big man, so his warriors were unable to carry him, but instead of doing this, they took apart his intestines and buried them on a small hill called Hodžina glavica (Imam's Peak). The legend has it that this event gave Drobnjaci their name (Drob is an archaic Serbo-Croatian word for intestines), although the name Drobnjaci is recorded earlier in history. However, its real connection to Gazi Husrev-beg's place of rest is unclear. His corpse was returned to Sarajevo, where it remains in a tomb in the courtyard of his mosque.

Endowment

Gazi Husrev-beg's endowment or Gazi Husrev-begov vakuf (trust or foundation) is based on his three vakufnama's (deeds of endowment), the first being issued November 1531, second on January 1537, and the third on November 1537. The three deeds of endowment were also legal basis for the establishment of the institution, the Gazi Husrev-begov Vakuf (or Gazi Husrev-beg's Endowment), whose primary purpose is to take care of the endowment's properties and support for the endowed established institutions. With it Husrev-beg bequeathed his property and wealth for the construction of facilities and the establishment of institutions, religious, educational, and public. The first vakufnama from 1531 required the construction of a mosque, humanitarian public kitchen (imaret) and guest house (musafirhana) and ḫāniqāh. The second issued on 1537 required for the Kuršumlija madrasa to be established and built, and also library to be equipped with books and other publications books purchased. The third from 1537 endowed additional property to support the mosque and other facilities.

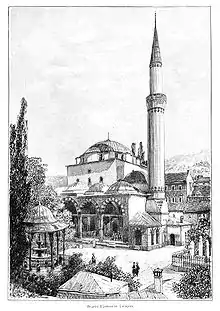

The endowment today consists of a number of buildings and institutions built and supported by the Gazi Husrev-begov Vakuf: the Gazi Husrev-beg Mosque, built in 1531 as the central object of the religious part of the endowment with a clock tower, Husrev-beg's and his turbe's and other supporting buildings, Gazi Husrev-begova Medresa with the Gazi Husrev-beg Library as the central objects of the educational part of the endowment, Gazi Husrev-begov bezistan, Morića Han as konak and Tašli Han as a caravanserai, Gazi Husrev-begov Hamam, imaret and musafirhana near clock tower, muvekkithane, šadrvan, hastahana as a hospital, mekteb, Gazi Husrev-begov Hanikah as a Dervish's monastery with a boarding school, and large number of shops around the Baščaršija.

The Museum of Gazi Husrev Beg is established in fall 2012 by the Gazi Husrev Beg Waqf (endowment).[4][5]

Most of these building are declared National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina by the Commission to preserve national monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

See also

References

- Zlatar, Behija (2010). Gazi Husrev-beg (in Bosnian). Orijentalni institut. p. 11. ISBN 9789958626135.

- Zlatar, Behija (2010). Gazi Husrev-beg (in Bosnian). Orijentalni institut. p. 17. ISBN 9789958626135.

- Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: a Short History. London: Papermac. pp. 67–68. ISBN 0-333-66215-6.

- "Historija". Gazi Husrev-begov vakuf (in Bosnian). Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- "Vakif". medresasa.edu.ba (in Bosnian). Retrieved 11 January 2022.

Sources

- Yugoslav Encyclopedia, article Husrev Beg, vol. IV, Hazim Sabanovič, Zagreb 1960

- GAMER, I, 1 (2012) s. 99-111, The other Ottoman Serhat in Europe: Ottoman territorial expansion in Bosnia and Croatia in first half of 16th century, Dino Mujadžević