Henry Clinton (British Army officer, born 1730)

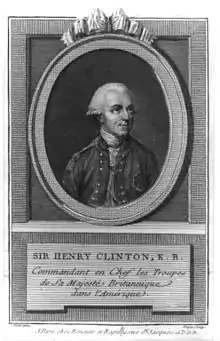

General Sir Henry Clinton, KB (16 April 1730 – 23 December 1795) was a British Army officer and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1772 and 1795. He is best known for his service as a general during the American War of Independence. He arrived in Boston in May 1775 and was the British Commander-in-Chief in America from 1778 to 1782. He was a Member of Parliament for many years due to the influence of his cousin Henry Pelham-Clinton, 2nd Duke of Newcastle. Late in life, he was named Governor of Gibraltar, but he died before assuming the post.

Sir Henry Clinton | |

|---|---|

Portrait attributed to Andrea Soldi, painted circa 1762–1765 | |

| Born | 16 April 1730 Newfoundland, British North America |

| Died | 23 December 1795 (aged 65) London, Great Britain |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1751–1793 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands held | Colonel, 12th Regiment of Foot Commander-in-Chief, North America Colonel, 7th (Queen's Own) Regiment of Light Dragoons |

| Battles/wars | War of the Austrian Succession Seven Years' War American War of Independence |

| Awards | Knight of the Bath |

| Spouse(s) |

Harriet Carter

(m. 1767; died 1772) |

| Other work | Member of Parliament Governor of Gibraltar (died before assuming office) |

| Signature |  |

Early life

Henry Clinton was born on 16 April 1730, to Admiral George Clinton and Anne Carle, the daughter of a general.[1] Early histories claimed his birth year as 1738, a date widely propagated even in modern biographic summaries; according to biographer William Willcox, Clinton claimed in a notebook found in 1958 to be born in 1730, and that evidence from English peerage records places the date of birth as 16 April.[1] Willcox also notes that none of these records give indication of the place of Clinton's birth.[2] Historian John Fredriksen claims that Clinton was born in Newfoundland;[3] his father was posted there from 1732 to 1738.[1]

Little is known of the earliest years of Clinton's life, or of his mother and the two sisters that survived to adulthood.[1] Given his father's naval career, where the family lived is uncertain. They were obviously well-connected to the seat of the Earls of Lincoln, from whom his father was descended, or the estate of the Dukes of Newcastle, to whom they were related by marriage.[2]

In 1739 his father, then stationed at Gibraltar, applied for the governorship of the Province of New York. He won the post in 1741 with the assistance of the Duke of Newcastle (who was his brother's brother-in-law).[4] He did not actually go to New York until 1743. He took young Henry with him, having failed to acquire a lieutenant's commission for the 12-year-old.[5] Henry's career would also benefit from the family connection to the Newcastles.[6]

Records of the family's life in New York are sparse. He is reported to have studied under Samuel Seabury on Long Island, suggesting the family may have lived in the country outside New York City.[6] Clinton's first military commission was to an independent company in New York in 1745. The next year his father procured for him a captain's commission, and he was assigned to garrison duty at the recently captured Fortress of Louisbourg.[6] In 1749, Clinton went to Britain to pursue his military career. It was two years before he received a commission as a captain in the Coldstream Guards.[7] His father, after he returned to London when his term as New York governor was over, procured for Clinton a position as aide to Sir John Ligonier in 1756.[8]

Seven Years' War

By 1758 Clinton had risen to be a lieutenant colonel in the 1st Foot Guards, which was later renamed the Grenadier Guards, and was a line company commander in the 2nd Battalion and was based in London. The 2nd Battalion, 1st Foot Guards, was deployed to Germany to participate in the Seven Years' War, arriving at Bremen on 30 July 1760 then joining the main Army, operating under Conway's Corps near Warberg.[9] George II died on 25 October 1760 and Clinton, along with all Officers of the Regiment, was amongst those listed in the renewal of commissions to George III, in London, on 27 October 1760.

Clinton was back with the 2nd Battalion coming out of winter quarters, at Paderborn in February 1761 and with the unit at the Battle of Villinghausen on 16 July 1761, then under Prince Ferdinand, the Hereditary Crown Prince, at the crossing of the Diemel, near Warburg, in August, before wintering near Bielefeld. His father died this year necessitating a return to England to resolve family affairs.

In 1762 the unit, part of the force led by Prince Ferdinand, was in action at the Battle of Wilhelmsthal on 24 June 1762. After this action they participated in cutting the French supply lines at the heights of Homberg on 24 July 1762 and secured artillery into position. It was after this engagement that the unit lost its commanding officer, Major General Julius Caesar who died at Elfershausen and is buried there. Clinton, now a colonel (seniority dated to 24 June 1762), was appointed as aide-de-camp to Prince Ferdinand by the start of 1762 and was with him when he attacked Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé at the Battle of Nauheim on 30 August 1762. Prince Ferdinand was wounded during this engagement and Clinton severely wounded forcing him to quit the field. This and the consequent siege of Cassel, were the last actions of the 1st Foot Guards in the Seven Years' War and Clinton returned to England.[10] Clinton had distinguished himself as an aide-de-camp to Brunswick, with whom he established an enduring friendship.[11]

During these early years, he formed a number of friendships and acquaintances, mostly with other officers serving in Brunswick's camp. These included Charles Lee and William Alexander, who styled himself "Lord Stirling"; both of these men would face Clinton as enemies in North America. He formed long-lasting and deep friendships with John Jervis, and William Phillips; Phillips later served under Clinton in North America, and Jervis rose to prominence in the Royal Navy. He also made the acquaintance of Charles Cornwallis, who would famously serve under him as well.[12]

Family and marriage

While Clinton was campaigning with the army in 1761, his father died. As the new head of the family, he had to unwind his father's affairs, which included sizable debts as well as arrears in pay. Battles he had with the Board of Trade over his father's unpaid salary lasted for years, and attempts to sell the land in the colonies went nowhere; these lands were confiscated during the American Revolution, and even his heirs were unable to recover any kind of compensation for them. His mother, who had a history of mental instability and played only a small part in his life, died in August 1767.[13]

On 12 February 1767, Clinton married Harriet Carter, the daughter of landed gentry,[14] and the couple settled into a house in Surrey. There is some evidence that the marriage was performed in haste; six months later, the household accounts contain evidence of a son, Frederick. Frederick died of an illness in 1774, two years after his mother. Although Clinton did not write of his marriage, it was apparently happy. The couple produced five children: Frederick, Augusta (1768), William Henry (1769), Henry Jr. (1771), and Harriet (1772). Clinton's wife died on 29 August 1772, eight days after giving birth to Harriet.[15] It took him over a year to recover from the grief. He took his in-laws into his house, and his wife's sisters took over the care of his children.[16] His second and third sons later continued the family tradition of high command.

Patronage

Upon the death of the Duke of Newcastle, his patronage was taken up by the latter's nephew and successor Henry Pelham-Clinton. Although he was sometimes instrumental in advancing Clinton's career, the new duke's lack of attention and interest in politics would at times work against Clinton. Clinton also complicated their relationship by treating the young duke more as an equal than as a noble who should be respected.[17] A second patron was King George III's brother the Duke of Gloucester. Clinton was appointed Gloucester's Groom of the Bedchamber in 1764, a position he continued to hold for many years. However, some of Gloucester's indiscretions left him out of favour at court, and he was thus not an effective supporter of Clinton.[18]

Peacetime service

In 1769, Clinton's regiment was assigned to Gibraltar, and Clinton served as second in command to Edward Cornwallis. During this time, Newcastle asked him to see after one of his (Newcastle's) sons who was serving in the garrison. The young man, described by his father as having "sloth and laziness" and "despicable behavior", was virtually unmanageable, and Clinton convinced the duke to put him into a French academy.[19]

Clinton was promoted to major-general in 1772,[20] and in the same year he obtained a seat in Parliament through Newcastle's influence.[21] He remained a Member of Parliament until 1784, first for Boroughbridge and subsequently for Newark-on-Trent.[22] In April 1774 he went on a military inspection tour of the Russian army in the Balkans. He inspected some of the battlefields of the Russo-Turkish War with his friend Henry Lloyd, a general in the Russian army, and had an audience with Joseph II in Vienna.[23] He very nearly had the chance to watch an artillery bombardment, but it was called off by the onset of peace negotiations. Clinton was at one point introduced to the Turkish negotiators, of whom he wrote that "they stared a little, but were very civil."[24] He returned to England in October 1774, and in February 1775 was ordered by King George to prepare for service in North America.[25]

American War of Independence

Boston

Clinton, along with Major Generals William Howe and John Burgoyne, was sent with reinforcements to strengthen the position of General Thomas Gage in Boston. They arrived on 25 May, having learned en route that the American War of Independence had broken out, and that Boston was under siege.[26] Gage, along with Clinton and Generals Howe and Burgoyne discussed plans to break the siege. Clinton was an advocate for fortifying currently unoccupied high ground surrounding Boston, and plans were laid to occupy those spots on 18 June.[27] However, the colonists learned of the plan and fortified the heights of the Charlestown peninsula on the night of 16–17 June, forcing the British leadership to rethink their strategy.[28]

In a war council held early on 17 June, the generals developed a plan calling for a direct assault on the colonial fortification, and Gage gave Howe command of the operation. Despite a sense of urgency (the colonists were still working on the fortifications at the time of the council), the attack did not begin until that afternoon. Clinton was assigned the role of providing reserve forces when requested by Howe.[29][30] After two assaults failed, Clinton, operating against his orders from General Gage, crossed over to Charlestown to organize wounded and dispirited troops milling around the landing area.[30]

On the third and successful assault against the redoubt on Breed's Hill, the position was taken and these troops, having rallied, arrived and drove the rebels back to Bunker Hill.[31] The battle was a victory for the British, but only at the heavy cost of over 1,000 casualties.[32] Clinton famously wrote of the battle that it was "A dear bought victory, another such would have ruined us."[33]

For the remainder of 1775 the siege became little more than a standoff, with the sides either unwilling or unable to mount an effective attack on the other. After Howe took command of the forces following General Gage's recall in September, the two of them established a working relationship that started out well, but did not take long to begin breaking down. Howe gave Clinton the command of Charlestown, but Clinton spent most of his time in Boston. He occupied the house of John Hancock, which he scrupulously cared for.[34] He hired a housekeeper named Mary Baddeley, the wife of a man who had supposedly been demoted because she refused an officer's advances. Clinton also hired Thomas Baddeley as a carpenter; the relationship Clinton established with Mary lasted the rest of his life,[35] although it was only platonic during his time in Boston.[36]

Cracks had already begun to form in his relationship with Howe when plans were developed for an expedition to the southern colonies, command of which went to Clinton. He asked Howe for specific officers to accompany him and authority that an independent commander might normally have, but Howe rebuffed him on all such requests.[37] In January 1776, Clinton sailed south with a small fleet and 1,500 men to assess military opportunities in the Carolinas.[38] During his absence his fears about the situation in Boston were realized when the Dorchester Heights were occupied and fortified by the rebels in early March, causing the British to evacuate Boston and retreat to Halifax, Nova Scotia.[39]

Campaigns in 1776

Clinton's expedition to the Carolinas was expected to meet a fleet sent from Europe with more troops for operations in February 1776. Delayed by logistics and weather, this force, which included Major General Charles Cornwallis as Clinton's second in command and Admiral Sir Peter Parker did not arrive off the North Carolina coast until May.[40] Concluding that North Carolina was not a good base for operations, they decided to assault Charleston, South Carolina, whose defenses were reported to be unfinished. Their assault, launched in late June, was a dismal failure. Clinton's troops were landed on an island near Sullivan's Island, where the rebel colonists had their main defenses, with the expectation that the channel between the two could be waded at low tide. This turned out not to be the case, and the attack was reduced to a naval bombardment.[41] The bombardment in its turn failed because the spongy palmetto logs used to construct the fort absorbed the force of the cannonballs without splintering and breaking.[42]

Continental Army

Clinton and Parker rejoined the main fleet to participate in General Howe's August 1776 assault on New York City. Clinton pestered Howe with a constant stream of ideas for the assault, which the commander in chief came to resent.[43] Howe did however adopt Clinton's plan for attacking George Washington's position in Brooklyn. At the 27 August Battle of Long Island, British forces led by Howe and Clinton, following the latter's plan, successfully flanked the American forward positions, driving them back into their fortifications on Brooklyn Heights.[44] However, Howe refused Clinton's recommendation that they follow up the overwhelming victory with an assault on the entrenched Americans, due to a lack of intelligence as to their strength and a desire to minimize casualties. Instead, Howe besieged the position, which the Americans abandoned without loss on 29 August.[45] General Howe was rewarded with a knighthood for his success.[46]

Howe then proceeded to take control of New York City, landing at Kip's Bay on Manhattan, with Clinton again in the lead.[47] Although Clinton again suggested moves to cut Washington's army off, Howe rejected them. In October Clinton led the army ashore in Westchester County in a bid to trap Washington between the Hudson and Bronx Rivers. However, Washington reached White Plains before Clinton did.[48] After a brief battle in which Washington was pushed further north, Howe turned south to consolidate control of Manhattan. By this time the relationship between the two men had broken down almost completely, with Howe, apparently fed up with Clinton's constant stream of criticisms and suggestions, refusing to allow Clinton even minor deviations in the army's marching route.[49]

In November Howe ordered Clinton to begin preparing an expedition to occupy Newport, Rhode Island, desired as a port by the Royal Navy. When Howe sent General Cornwallis into New Jersey to chase after Washington, Clinton proposed that, rather than taking Newport, his force should be landed in New Jersey in an attempt to envelop Washington's army.[50] Howe rejected this advice, and Clinton sailed for Newport in early December, occupying it in the face of minimal opposition.[51]

Campaigns in 1777

In January 1777 Clinton was given leave to return to England.[52] Planning for the 1777 campaign season called for two campaigns, one against Philadelphia, and a second that would descend from Montreal on Lake Champlain to Albany, New York, separating the New England colonies. Since General Howe was taking leadership of the Philadelphia campaign, Clinton contested for command of the northern campaign with Burgoyne. Howe supported him in this effort, but Burgoyne convinced King George and Lord Sackville to give him the command.[53] The king refused Clinton's request to resign, and ordered him back to New York to serve again as Howe's second in command. He was placated with a knighthood, but was also forbidden to publish accounts of the disastrous Charleston affair.[54] He was formally invested with the Order of the Bath on 11 April, and sailed for New York on the 29th.[55]

When Clinton arrived in New York in July, Howe had not yet sailed for Philadelphia.[56] Clinton was surprised and upset that he would be left to hold New York with 7,000 troops, dominated by Loyalist formations and Hessians, an arrangement he saw as inadequate to the task. He also quite bluntly informed Howe of the defects he saw in Howe's plan, which would isolate Burgoyne from any reasonable chance of support by either Howe or Clinton.[57] He presciently wrote after learning that much of Washington's force had left the New York area, "I fear it bears heavy on Burgoyne ... If this campaign does not finish the war, I prophesy that there is an end of British dominion in America."[58]

Burgoyne's campaign ended in disaster; Burgoyne was defeated at Saratoga and surrendered shortly after.[59] Clinton attempted to support Burgoyne, but the delay in arrival of reinforcements put off the effort. In early October, Clinton captured two forts in the Hudson River highlands, and sent troops up the river toward Albany.[60] The effort was too little and too late, and was cut off when he received orders from Howe requesting reinforcements. Howe's campaign for Philadelphia had been a success, but he had very nearly suffered a defeat in the Battle of Germantown.

As the commander in New York, Clinton lived at No. 1 Broadway, on Bowling Green, a house occupied by later commandants General Robertson and General Pattison.[61] He was obligated to do a certain amount of entertaining. This he did, although he chafed at the costs involved. He was eventually joined by the Baddeleys. Mary Baddeley resumed her role as housekeeper, which he appreciated in part because of her excellent managerial skills.[62] She apparently rebuffed Clinton's romantic overtures until she discovered her husband had been cheating on her. Clinton procured a position in one of the Loyalist regiments for her husband, and tried without success to get him transferred out of New York.[63]

Commander-in-Chief

._(NYPL_b13512824-420891)_(cropped).tiff.jpg.webp)

General Howe submitted his resignation as Commander-in-Chief in America in the wake of the 1777 campaigns, and Clinton was on the short list of nominees to replace him—despite being mistrusted by Prime Minister North, principally over his many complaints and requests to resign. Clinton was formally appointed to the post on 4 February 1778. Word of this did not arrive until April, and Clinton assumed command in Philadelphia in May 1778.[64] France had formally entered the war on the American side by this time. Clinton was consequently ordered to withdraw from Philadelphia and send 5,000 of his troops to the economically important Caribbean. For the rest of the war, Clinton received few reinforcements as a consequence of the globalisation of the conflict with France.[65] His orders were to strengthen areas in America that were firmly under British control, and do no more than conduct raiding expeditions in the American-controlled areas.[66]

There was a shortage of transports for all of the Loyalists fleeing Philadelphia, so Clinton acted against his direct orders and decided to move the army to New York by land instead of by sea.[67] He marched to New York and fought a battle with Washington's army at Monmouth Court House on 28 June.[68] Clinton burnished his reputation at home by writing a report on the movement that greatly exaggerated the size of Washington's Continental Army and minimised the British casualties at Monmouth.[69]

Arriving in New York, he and Admiral Howe were faced with a French fleet outside the harbour. Fortunately, Admiral d'Estaing decided against crossing the bar into the harbour, and sailed instead for Newport.[70] Once Clinton learned of his destination, he marshalled troops to reinforce the Newport garrison while Lord Howe sailed to meet d'Estaing. Both fleets were scattered by a storm, and the Americans failed to take Newport before Clinton arrived.[71] Clinton sent the supporting force on a raid of nearby communities, while he returned to New York to organize the troops that were to be sent southward.[72]

Clinton sent a detachment to strike at Georgia that took Savannah in December, and it gained a tenuous foothold at Augusta in January 1779.[73] He also detached troops for service in the West Indies in a plan to capture St. Lucia; the expedition was a success, compelling a French surrender not long before the French fleet arrived.[74]

Clinton managed to establish a harmonious relationship with William Eden, a member of the Carlisle Peace Commission. This commission had been sent in a vain attempt at reconciliation with the American Congress. Despite its failures, Eden and Clinton got along, and Eden promised to make sure that Clinton's dispatches received favourable distribution in England.[75]

Clinton found himself dealing with the tit-for-tat murders taking place between the Patriots and Loyalists, and he was in office when Captain Huddy was murdered, which eventually led to the Asgill Affair. His dealings with the Board of Associated Loyalists and their President Governor William Franklin were his priority in the weeks before his departure. By mid-May 1782, Clinton informed the Secretary for the Colonies in Whitehall of the situation regarding Huddy's murder. He wrote to the Right Honourable Wellbore Ellis on 11 May 1782:

"I cannot, Sir, too much lament the great Imprudence shown by the Refugees on this Occasion – as these very ill timed Effects of their Resentment may probably introduce a System of War horrid beyond Description. Nor can I sufficiently pity my Successor’s having the Misfortune of coming to the Command at so disagreeable and critical a Period … Allowance ought to be made for Men whose Minds may possibly be roused to Vengeance by Acts of Cruelty committed by the Enemy on their dearest Friends … I cannot but observe that the Conduct of the Board during this whole Transaction has been extraordinary, not to say, reprehensible; … for the purpose (it is presumed) of exciting the War of indiscriminate Retaliation, which they appear to have long thirsted after."[76]

Politics

With the 1778 campaign season closed, Clinton considered options for action in 1779. Although he felt that Britain would be best served by withdrawing to the frontiers, popular opinion at home, as well as that of the king and George Germain, dictated otherwise. Germain felt that raiding expeditions should be conducted "with spirit and humanity" to destroy American commerce and privateering;[77] this strategy was one Clinton disliked.[78] Militarily, Clinton and Washington did little more than stare at each other across the lines of New York City. Clinton ordered two major raiding expeditions, one against Connecticut, the other against Chesapeake Bay, while Washington detached troops to deal with the increasing frontier war, which was primarily orchestrated from Quebec.

Early in 1779 Clinton sent his trusted aide, Lieutenant Duncan Drummond, to England in order to argue Clinton's request to be recalled. Drummond was unsuccessful in this: despite the intervention of the Duke of Newcastle, the king refused to even consider granting Clinton leave, claiming that Clinton was "the only man who might still save America".[79] William Eden also interceded in an attempt to improve Clinton's situation, but political divisions in the government and the prospect of Spanish entry into the war meant that Clinton ended up with very little support.[80] Clinton also complained about the lack of naval support being provided by Admiral James Gambier, with whom he also had a difficult relationship. He eventually sent London a list of admirals he thought he could work with. None of them were chosen, and Gambier was replaced temporarily by George Collier before his permanent replacement, Mariot Arbuthnot, arrived.[81]

After the Chesapeake raid Clinton drove the Americans from a key crossing of the Hudson River at Stony Point, New York. Clinton had hoped that, with an expected reinforcement of troops from Europe, he could then attack either Washington's army or its supply lines, forcing Washington out of his well-defended mountain positions.[82] However, the reinforcements, including Admiral Arbuthnot, were late in arriving, and Stony Point was retaken by the Americans after Clinton weakened its garrison to supply men for the Connecticut raids. The Americans chose not to hold Stony Point, and Clinton reoccupied it. However, Clinton's opponents used the American success to criticise him, calling him "undetermined" and "feeble".[83] A similar action against a British outpost in New Jersey gave them further ammunition, and soured British morale.[84] Further actions from New York were rendered impossible by the need for the naval squadron to address the American expedition to dislodge a newly established British outpost in Penobscot Bay.[85]

On 30 June 1779, Clinton issued what has become known as the Philipsburg Proclamation (so named because it was issued from his headquarters at the Philipsburg Manor House in Westchester County, New York). This proclamation institutionalized in the British Army an offer of freedom to enlisted runaway slaves that had first been made in a similar proclamation by Virginia Governor Lord Dunmore in 1775. He justified this offer by citing the fact that the Continental Army was also actively recruiting blacks. The proclamation led to a flood of fugitive slaves making their way to British lines to take advantage of the offer,[86] and the issue of slave repatriation would complicate Anglo-American relations as the war was ending.[87]

Southern strategy

Clinton's relationship with Arbuthnot got off to a bad start. Rumors of a French fleet headed for northern ports (Halifax, Newport, or New York) pulled the leaders in different directions, and put off plans to withdraw from Newport for the purposes of strengthening the New York garrison (which had been weakened by disease) on at least one occasion.[88] However, the French instead besieged Savannah, Georgia, with American assistance, and failed disastrously in the attempt. This convinced Clinton that an expedition against South Carolina held promise. Loyalist support was said to be strong there, and the people were said to be "sick of their opposition to government" and the British blockade of their ports.[89]

Clinton began to assemble a force an expedition to take Charleston, withdrawing the forces from Newport for the purpose. Clinton took personal command of this campaign, and the task force with 14,000 men sailed south from New York at the end of the year. By early 1780, Clinton had brought Charleston under siege. In May, working together with Admiral Arbuthnot, he forced the surrender of the city, with its garrison of 5,000, in a stunning and serious defeat for the rebel cause. Arbuthnot and Clinton did not work together well during the siege, and their feuding lasted into 1781, with disastrous results for the unity of the British high command.[90][91] Clinton's relationship with Cornwallis also deteriorated further during the siege, improving slightly after the American surrender and Clinton's departure for New York.[92]

From New York, he oversaw the campaign in the South, and his correspondence to Cornwallis throughout the war showed an active interest in the affairs of his southern army.[93] However, as the campaign progressed, he grew further and further away from his subordinate. As the campaign drew to a close, the correspondence became more and more acrimonious. Part of this may be due to George Germain, whose correspondence with Cornwallis may have convinced the junior officer to start disregarding the orders of his superior and consider himself to be an independent command.[94]

In 1782, after fighting in the North American theater ended with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, Clinton was replaced as Commander-in-Chief by Sir Guy Carleton, and he returned to England.

Later career

In 1783, Clinton published a Narrative of the Campaign of 1781 in North America in which he attempted to lay the blame for the 1781 campaign failures on General Cornwallis. This was met with a public response by Cornwallis, who leveled his own criticisms at Clinton. Clinton also resumed his seat in Parliament, serving until 1784.[95]

Not much is known about what Clinton did from 1784 until he was re-elected to Parliament in 1790 for Launceston in Cornwall, a pocket borough controlled by his cousin Newcastle. Three years later, in October 1793, Clinton was promoted to full general. The following July he was appointed Governor of Gibraltar, but he died at Portland Place before he was able to assume that post.[96]

He was buried in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.

Legacy

Sir Henry Clinton's legacy in the eyes of historians has been mixed. He held the command in America for four years, ending in disaster,[97] and as a result, he is widely seen to share in the blame for the defeat. The biographer William Willcox, in his analysis of Clinton's tenure in North America, observes that at times, "Sir Henry's ideas were not carried out for reasons that lay to some extent within himself"[98] and that he and Admiral Graves "apparently ignored the danger" of de Grasse in 1781.[99] However, Willcox notes that campaign plans Clinton formulated for 1777, 1779 and 1780 were frustrated by external events that he could not control, and Willcox generally blames Cornwallis for the failure of the Carolina campaign.[100] In contrast, Cornwallis' biographers Franklin and Mary Wickwire point out that Cornwallis's failures are at least partially attributable to directives of Clinton that left him with relatively inadequate troop strength and irregular supply lines.[101]

Major James Wemyss, who served under Clinton, wrote that he was "an honourable and respectable officer of the German school; having served under Prince Ferdinand of Prussia and the Duke of Brunswick. Vain, open to flattery; and from a great aversion to all business not military, too often misled by aides and favourites." However, also pointed out that Clinton's interests were narrow and that he was crippled by self-distrust.[97] Colonel Sir Charles Stuart described him as "fool enough to command an army when he is incapable of commanding a troop of horse." However, the historian Piers Mackesy writes that he was "a very capable general in the field."[97]

Letters from General Sir Henry Clinton during the Revolutionary War can be found in the political papers of his cousin, Henry Pelham-Clinton, in the Newcastle (Clumber) Collection held at Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham Information Services.[102]

In 1937, the William L. Clements Library at University of Michigan library acquired a number of manuscripts belonging to Clinton. They were first sorted and organized by the colonial American historian Howard Henry Peckham and are now part of the collection of this library.[103]

Notes

- Willcox, 1964, p. 5.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 6.

- Fredriksen, 2001, p. 107.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 7.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 8.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 9.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 10.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 13.

- Hamilton, 1874, Vol 2, pp. 174–191.

- Hamilton, 1874, Vol 2, p. 190.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 18.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 22–23.

- Willcox, 1694, pp. 20–21.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 25.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 26–29.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 32.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 21.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 22.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 28.

- "No. 11251". The London Gazette. 23 May 1772. p. 2.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 29.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 29, 474.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 32–34.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 35.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 35–36.

- Ketchum, 2014, p. 2.

- Ketchum, 2014, p. 46.

- Ketchum, 2014, pp. 110–111.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 48.

- Ketchum, 2014, p. 164.

- Ketchum, 2014, pp. 181–182.

- Ketchum, 2014, p. 190.

- Ketchum, 2014, p. 183.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 59.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 60.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 69.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 67.

- Billias, 1969, p. 76.

- Ketchum, 2014, pp. 214–218.

- Billias, 1969, pp. 76–77.

- Billias, 1969, p. 77.

- Russell, 2002, p. 217.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 104.

- Gruber, 1972, pp. 111–112.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 107.

- Hadden, 1884, p. 375.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 110–111.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 113.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 114.

- Gruber, 1972, p. 135.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 123–124.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 127.

- Mintz, 1990, pp. 113–115.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 137.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 141.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 153.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 154.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 157.

- Mintz, 1990, pp. 221–223.

- Mintz, 1990, pp. 203–205.

- Duncan, Francis (1879). History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery (1716-1783): Compiled from the Original Records. Vol. 1. London: John Murray.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 171–172.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 199.

- Billias, 1969, pp. 61, 82.

- Billias, 1969, p. 83.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 222–223.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 227.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 233–237.

- Leckie, 1993, p. 401.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 238–239.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 242–250.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 251.

- Wilson, 2005, pp. 70–101.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 254.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 254–255.

- "A letter from Sir Henry Clinton to Wellbore Ellis on 11 May 1782[Secretary for the Colonies] enclosing documents relating to the murder of Joshua Huddy". Records of the Colonial Office, Commonwealth and Foreign and Commonwealth Offices, Empire Marketing Board, and related bodies relating to the administration of Britain's colonies, Box: CO 5/105/020. The National Archives. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 256–257.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 277.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 263.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 264–266.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 273–274.

- Johnston, 1900, pp. 43–44.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 278.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 279.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 281.

- Lanning, 2005, p. 134.

- Lanning, 2005, p. 158.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 289–293.

- Willcox, 1964, pp. 293–294.

- Harvey, 2002.

- Wyatt, 1959, pp. 3–26. Wyatt argues that Clinton had mild neurosis and was unable to work with those whom he considered equal.

- Borick, 2003, pp. 235–236.

- Cornwallis Papers, The National Archives. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- Germain Papers, Clements Library, Ann Arbor. Germain Papers Archived 3 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- Sir Henry Clinton. Notable Names Database. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- Gruber, Ira D. (2004). "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Clinton, Sir Henry (1730–1795)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5681. Retrieved 16 September 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Mackesy, 1992, p. 213.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 498.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 497.

- Willcox, 1964, p. 493.

- Wickwire, 1970, pp. 135–137.

- "Sir Henry Clinton". University of Nottingham. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- Quatro Journal: The Clements Library Associates, 1995, p. 2.

Bibliography

- Bicheno, Hugh (April 2003). Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolutionary War. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-715625-1.

- Billias, George Athan (1969). George Washington's Opponents. New York: William Morrow. OCLC 11709.

- Borick, Carl P. (February 2003). A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-487-7.

- Fredriksen, John C. (2001). America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-603-3. OCLC 248864750.

- Gruber, Ira (1972). The Howe Brothers and the American Revolution. New York: Atheneum Press. OCLC 1464455.

- Hadden, James M.; Rogers, Horatio (1884). A Journal Kept in Canada and Upon Burgoyne's Campaign in 1776 and 1777 by Lieut. James M. Hadden. J. Munsell's Sons. p. 375. OCLC 2130358.

- Hamilton, Sir Frederick William (1874). The Origin and History of the First Or Grenadier Guards. John Murray, London.

- Harvey, Robert (May 2002). A Few Bloody Noses: The Realities and Mythologies of the American Revolution. Overlook Hardcover. ISBN 1-58567-273-4.

- Hibbert, Christopher (April 2002). Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through British Eyes. W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-32293-9.

- Johnston, Henry Phelps (1900). The Storming of Stony Point on the Hudson. New York City: James T. White & Co. p. 43.

- Ketchum, Richard (1999). Decisive Day: The Battle of Bunker Hill. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-6099-5. — eBook

- Lanning, Michael (2005). African Americans in the Revolutionary War. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 978-0-8065-2716-1. OCLC 62311668.

- Leckie, Robert (1993). George Washington's War: The Saga of the American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-092215-3. OCLC 29748139.

- Lengel, Edward (2005). General George Washington. New York: Random House Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8129-6950-4. OCLC 255642134.

- Mackesy, Piers (1992). War for America: 1775–1783. University of Nebraska Press. online edition

- McEvedy, C. (1988). The Penguin Atlas of North American History to 1870. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051128-8.

- Mintz, Max M. (1990). The Generals of Saratoga: John Burgoyne and Horatio Gates. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04778-3. OCLC 644565187.

- Russell, David Lee (2002). Victory on Sullivan's Island: the British Cape Fear/Charles Town Expedition of 1776. Haverford, PA: Infinity. ISBN 978-0-7414-1243-0. OCLC 54439188.

- Wickwire, Franklin and Mary (1970). Cornwallis: The American Adventure. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 62690.

- Willcox, William (1964). Portrait of a General: Sir Henry Clinton in the War of Independence. New York: Alfred A Knopf. OCLC 245684727.

- Wilson, David K. (2005). The Southern Strategy: Britain's Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-573-3. OCLC 56951286.

- Wyatt, F. (January 1959). "Sir Henry Clinton: a Psychological Exploration in History". William and Mary Quarterly. 16 (1): 4–26. doi:10.2307/1918848. JSTOR 1918848.

- In Memory of Howard Henry Peckham (PDF). The Quatro. 1995. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

Further reading

- Buchanan, John (February 1997). The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution and the Carolinas. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-16402-X.

- Clement, R. (January–March 1979). "The World Turned Upside down At the Surrender of Yorktown". Journal of American Folklore. 92 (363): 66–67. doi:10.2307/538844. JSTOR 538844.

- Ferling, John (October 1988). The World Turned Upside Down: The American Victory in the War of Independence. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-25527-X.

- Hyma, Albert (1957). Sir Henry Clinton and the American Revolution. Hyma.

- Newcomb, Benjamin H., ‘Clinton, Sir Henry (1730–1795)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68518. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson. The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire (2014). (subscription or UK public library membership required)

External links

- Biography of Henry Clinton, with links to online catalogues, from Manuscripts and Special Collections at The University of Nottingham

- "Archival material relating to Henry Clinton". UK National Archives.

- 'Conflict': e-learning resource from Manuscripts and Special Collections at The University of Nottingham, including digitised images of some of Henry Clinton's letters

- Henry Clinton papers William Clements Library.