Sam Houston

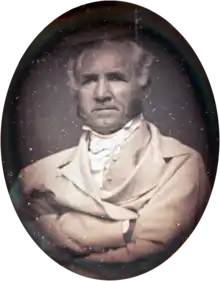

Samuel Houston (/ˈhjuːstən/ ⓘ, HEW-stən; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played an important role in the Texas Revolution. He served as the first and third president of the Republic of Texas and was one of the first two individuals to represent Texas in the United States Senate. He also served as the sixth governor of Tennessee and the seventh governor of Texas, the only individual to be elected governor of two different states in the United States.

Sam Houston | |

|---|---|

| |

| 7th Governor of Texas | |

| In office December 21, 1859 – March 15, 1861 | |

| Lieutenant | Edward Clark |

| Preceded by | Hardin Richard Runnels |

| Succeeded by | Edward Clark |

| United States Senator from Texas | |

| In office February 21, 1846 – March 3, 1859 | |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | John Hemphill |

| 1st & 3rd President of Texas | |

| In office December 21, 1841 – December 9, 1844 | |

| Vice President | Edward Burleson |

| Preceded by | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

| Succeeded by | Anson Jones |

| In office October 22, 1836 – December 10, 1838 | |

| Vice President | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

| Preceded by | David G. Burnet (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

| Member of the Texas House of Representatives from the San Augustine district | |

| In office 1839–1841 | |

| 6th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office October 1, 1827 – April 16, 1829 | |

| Lieutenant | William Hall |

| Preceded by | William Carroll |

| Succeeded by | William Hall |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Tennessee's 7th district | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1827 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | John Bell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Samuel Houston March 2, 1793 Rockbridge, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | July 26, 1863 (aged 70) Huntsville, Texas, C.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (before 1830) Democratic (1846–1854) Know Nothing (1855–1856) Independent (1856–1863) |

| Spouses | |

| Education | Maryville College |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | United States Army Texan Army |

| Years of service | 1813–1818 (U.S. Army) 1835–1836 (Texan Army) |

| Rank | First Lieutenant (U.S. Army) Major General (Texan Army) |

| Unit | 39th Infantry Regiment (U.S. Army) |

| Commands | Army of the Republic of Texas (Texan Army) |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 Creek War • Battle of Horseshoe Bend Texas Revolution • Battle of San Jacinto |

Born in Rockbridge County, Virginia, Houston and his family relocated to Maryville, Tennessee, when he was a teenager. Houston later ran away from home, spending about three years living with the Cherokee,[1] becoming known as “Raven." He served under General Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812; afterwards, and despite his earlier connections to the Cherokee people, he presided over the mass removal of Cherokee from Tennessee. With the support of Jackson, among others, Houston won election to the United States House of Representatives in 1823. He strongly supported Jackson's presidential candidacies and, in 1827, Houston was elected as the governor of Tennessee. In 1829, after divorcing his first wife, Houston resigned from office, and moved to the Arkansas Territory.

Houston settled in Texas in 1832. After the Battle of Gonzales, he helped organize Texas's provisional government and was selected as the top-ranking official in the Texian Army. He led the Texan Army to victory at the Battle of San Jacinto, the decisive battle in Texas's war for independence against Mexico. After the war, Houston won the 1836 Texan presidential election. He left office due to term limits in 1838, but won another term in the 1841 Texas presidential election. Houston played a key role in the annexation of Texas by the United States in 1845 and, in 1846, was elected to represent Texas in the United States Senate. He joined the Democratic Party and supported President James K. Polk's prosecution of the Mexican–American War.

His Senate record was marked by his unionism and opposition to extremists from both the North and South. He voted for the Compromise of 1850, which settled many of the residual territorial issues from the Mexican–American War and the annexation of Texas. Houston owned slaves throughout his life, and was a centrist on the issue of slavery. He voted against the Kansas–Nebraska Act, as he believed it would lead to increased sectional tensions over slavery, and his opposition to that act led him to leave the Democratic Party. He was an unsuccessful candidate for the presidential nomination of the American Party in the 1856 presidential election, as well as for the Constitutional Union Party in the 1860 presidential election. In 1859, Houston won election as the governor of Texas. In this role, he opposed secession, but unsuccessfully sought to keep Texas out of the Confederate States of America. He was forced out of office in 1861, and died two years later in 1863. Houston's name has been honored in numerous ways, and he is the eponym of the city of Houston, the fourth-most-populous city in the United States.

Early life

Samuel Houston was born in Rockbridge County, Virginia on March 2, 1793 to Samuel Houston and Elizabeth Paxton. Both of Houston's parents were descended from Scottish and Irish immigrants who had settled in Colonial America in the 1730s,[2] including his great-grandfather John Houston.[3] Houston's father was descended from Ulster Scots people.[4][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] Samuel inherited the Timber Ridge plantation and mansion in Rockbridge County, Virginia, which was worked by enslaved African Americans. During the American Revolutionary War, Captain Houston served in Morgan's Rifle Brigade as a paymaster.[4] He served in the Virginia militia, which required him to pay his own expenses and to be away from his family for long periods of time. Thus, the plantation and his family's finances suffered.[3]

He had five brothers and three sisters:[2] Paxton, Robert, James (married Patience Bills), John, William (married Mary Ball), Isabella, Mary (married Matthew Wallace, followed by his nephew, Williams Wallace), and Eliza (who married Samuel Moore).[6]

His father, Samuel Sr., planned to sell Timber Ridge[lower-alpha 3] and move west to Tennessee, where land was less expensive, but he died in 1806. Elizabeth, his mother, followed through on those plans, settling the family near Maryville, Tennessee, the seat of Blount County. At that time, Tennessee was on the American frontier, and even larger towns like Nashville were vigilant against Native American raids.[8][9] He had dozens of cousins who lived in the surrounding area[2] of east-central Tennessee.[10] When they arrived, Elizabeth cleared the land, built a house, and planted crops. Her oldest children, Paxton, Isabella, and Robert died within a few years after they arrived in Tennessee. Elizabeth relied on James and John to run the store in Maryville, to operate the farm, and to watch over the younger children.[7]

Houston had a carefree disposition, however, and liked to escape to explore the frontier. He was at odds with the concepts of hell and damnation preached by his mother's religion, Presbyterianism, and he was not interested in schooling. However, he did take an interest in his father's library, reading works by classical authors like Virgil, as well as more contemporary works by authors such as Jedidiah Morse.[11]

Not interested in farming and working in the family store, at the age of 16, he left his family to live with a Cherokee tribe, led by Chief John Jolly (Cherokee name: Ahuludegi, also spelled Oolooteka)[9][8] on Hiwassee Island.[12] Houston formed a close relationship with Jolly and learned the Cherokee language, becoming known as ‘Raven.'[13] According to James L. Haley, he appreciated the "free and unsophisticated spiritual expression of the Native Americans."[14] He left the tribe to return to Maryville in 1812, and he was hired at age 19 for a term as the schoolmaster of a one-room schoolhouse.[15] He attended Porter Academy, where he was taught by Rev. Isaac L. Anderson, founder of Maryville College.[16]

According to biographer John Hoyt Williams, Houston was not close with his siblings or his parents, and he rarely spoke of them in his later life.[2] Haley states that he was interested in his younger brother's and his sisters' welfare when he lived on Hiwassee Island. He felt used by the rest of the family.[14]

War of 1812 and aftermath

In 1812, Houston enlisted in the United States Army, which then was engaged in the War of 1812 against Britain and Britain's Native American allies.[17] He quickly impressed the commander of the 39th Infantry Regiment, Thomas Hart Benton, and by the end of 1813, Houston had risen to the rank of third lieutenant. In early 1814, the 39th Infantry Regiment became a part of the force commanded by General Andrew Jackson, who was charged with putting an end to raids by a faction of the Muscogee (or "Creek") tribe in the Old Southwest.[18] Houston was wounded badly in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, the decisive battle in the Creek War. Although army doctors expected him to die of his wounds, Houston survived and convalesced in Maryville and other locations. While many other officers lost their positions after the end of the War of 1812 due to military cutbacks, Houston retained his commission with the help of Congressman John Rhea.[19] During that time he was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant.[9]

Sometime in early 1817, Sam Houston was assigned to a clerical position in Nashville, serving under the adjutant general for the army's Southern Division. Later in the year, Jackson appointed Houston as a sub-agent to handle the removal of Cherokee from East Tennessee.[20] In February 1818, he received a strong reprimand from Secretary of War John C. Calhoun after he wore Native American dress to a meeting between Calhoun and Cherokee leaders, beginning an enmity that lasted until Calhoun's death in 1850.[21] Angry over the incident with Calhoun and an investigation into his activities, Houston resigned from the army in 1818. He continued to act as a government liaison with the Cherokee, and in 1818, he helped some of the Cherokee resettle in Arkansas Territory.[22]

Early political career

After leaving government service, Houston began an apprenticeship with Judge James Trimble in Nashville. He quickly won admission to the state bar and opened a legal practice in Lebanon, Tennessee. With the aid of Governor Joseph McMinn, Houston won election as the district attorney for Nashville in 1819. He was also appointed as a major general of the Tennessee militia.[9][23] Like his mentors, Houston was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, which dominated state and national politics in the decade following the War of 1812. Tennessee gained three seats in the United States House of Representatives after the 1820 United States Census, and, with the support of Jackson and McMinn, Houston ran unopposed in the 1823 election for Tennessee's 9th congressional district.[24] In his first major speech in Congress, Houston advocated for the recognition of Greece, which was fighting a war of independence against the Ottoman Empire.[25]

Houston strongly supported Jackson's candidacy in the 1824 presidential election, which saw four major candidates, all from the Democratic-Republican Party, run for president. As no candidate won a majority of the vote, the House of Representatives held a contingent election, which was won by John Quincy Adams.[26] Supporters of Jackson eventually coalesced into the Democratic Party, and those who favored Adams became known as National Republicans. With Jackson's backing, Houston won election as governor of Tennessee in 1827.[27] Governor Houston advocated the construction of internal improvements such as canals, and sought to lower the price of land for homesteaders living on public domain. He also aided Jackson's successful campaign in the 1828 presidential election.[28]

In January 1829, Houston married Eliza Allen, the daughter of wealthy plantation owner John Allen of Gallatin, Tennessee. The marriage quickly fell apart, possibly because Eliza loved another man.[29] In April 1829, following the collapse of his marriage, Houston resigned as governor of Tennessee. Shortly after leaving office, he traveled to Arkansas Territory to rejoin the Cherokee.[30]

Political exile and controversy

Houston was reunited with Ahuludegi's group of Cherokee in mid-1829.[31] Because of Houston's experience in government and his connections with President Jackson, several local Native American tribes asked Houston to mediate disputes and communicate their needs to the Jackson administration.[32] In late 1829, the Cherokee accorded Houston tribal membership and dispatched him to Washington to negotiate several issues.[33] In anticipation of the removal of the remaining Cherokee east of the Mississippi River, Houston made an unsuccessful bid to supply rations to the Native Americans during their journey.[34] When Houston returned to Washington in 1832, Congressman William Stanbery alleged that Houston had placed a fraudulent bid in 1830 in collusion with the Jackson administration. On April 13, 1832, after Stanbery refused to answer Houston's letters regarding the incident, Houston beat Stanbery with a cane.[35] After the beating, the House of Representatives brought Houston to trial. By a vote of 106 to 89, the House convicted Houston, and Speaker of the House Andrew Stevenson formally reprimanded Houston.[9] A federal court also required Houston to pay $500 in damages.[36]

Texas Revolution

In mid-1832, Houston's friends William H. Wharton and John Austin Wharton wrote to convince him to travel to the Mexican possession of Texas, where unrest among the American settlers was growing.[37] The Mexican government had invited Americans to settle the sparsely populated region of Texas, but many of the settlers, including the Whartons, disliked Mexican rule. Houston crossed into Texas in December 1832, and shortly thereafter, he was granted land in Texas.[38] Houston was elected to represent Nacogdoches, Texas at the Convention of 1833, which was called to petition Mexico for statehood (at the time, Texas was part of the state of Coahuila y Tejas). Houston strongly supported statehood, and he chaired a committee that drew a proposed state constitution.[39] After the convention, Texan leader Stephen F. Austin petitioned the Mexican government for statehood, but he was unable to come to an agreement with President Valentín Gómez Farías. In 1834, Antonio López de Santa Anna assumed the presidency, took on new powers, and arrested Austin.[40] In October 1835, the Texas Revolution broke out with the Battle of Gonzales, a skirmish between Texan forces and the Mexican Army. Shortly after the battle, Houston was elected to the Consultation, a congregation of Texas leaders.[41]

Along with Austin and others, Houston helped organize the Consultation into a provisional government for Texas. In November, Houston joined with most other delegates in voting for a measure that demanded Texas statehood and the restoration of the 1824 Constitution of Mexico. The Consultation appointed Houston as a major general and the highest-ranking officer of the Texian Army,[9][17] though the appointment did not give him effective control of the militia units that constituted the Texian Army.[42] Houston helped organize the Convention of 1836, where the Republic of Texas declared independence from Mexico, and appointed him as Commander-in-Chief of the Texas Army. Shortly after the declaration, the convention received a plea for assistance from William B. Travis, who commanded Texan forces under siege by Santa Anna at the Alamo. The convention confirmed Houston's command of the Texian Army and dispatched him to lead a relief of Travis's force, but the Alamo fell before Houston could organize his forces at Gonzales, Texas. Seeking to intimidate Texan forces into surrender, the Mexican army killed every defender at the Alamo; news of the defeat outraged many Texans and caused desertions in Houston's ranks.[43] Commanding a force of about 350 men that numerically was inferior to that of Santa Anna, Houston retreated east across the Colorado River.[44]

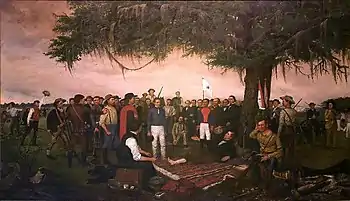

Though the provisional government, as well as many of his own subordinates, urged him to attack the Mexican army, Houston continued the retreat east, informing his soldiers that they constituted "the only army in Texas now present ... There are but a few of us, and if we are beaten, the fate of Texas is sealed."[45][lower-alpha 4] Santa Anna divided his forces and finally caught up to Houston in mid-April 1836.[47] Santa Anna's force of about 1,350 soldiers trapped Houston's force of 783 men in a marsh; rather than pressing the attack, Santa Anna ordered his soldiers to make camp. On April 21, Houston ordered an attack on the Mexican army, beginning the Battle of San Jacinto. The Texans quickly routed Santa Anna's force, though Houston's horse was shot out under him and his ankle was shattered by a stray bullet.[9][48] In the aftermath of the Battle of San Jacinto, a detachment of Texans captured Santa Anna.[49] Santa Anna was forced to sign the Treaty of Velasco, granting Texas its independence. Houston stayed briefly for negotiations, then returned to the United States for treatment of his ankle wound.[50]

President of Texas

Victory in the Battle of San Jacinto made Houston a hero to many Texans, and he won the 1836 Texas presidential election, defeating Stephen F. Austin, another former governor who would also receive the honor of having the city of Austin named after him, and Henry Smith. Houston took office on October 22, 1836, after interim president David G. Burnet resigned.[51] During the presidential election, the voters of Texas overwhelmingly indicated their desire for Texas to be annexed by the United States. Houston, meanwhile, faced the challenge of assembling a new government, putting the country's finances in order, and handling relations with Mexico. He selected Thomas Jefferson Rusk as secretary of war, Smith as secretary of the treasury, Samuel Rhoads Fisher as secretary of the navy, James Collinsworth as attorney general, and Austin as secretary of state.[52][lower-alpha 5] Houston sought normalized relations with Mexico, and despite some resistance from the legislature, arranged the release of Santa Anna.[54] Concerned about upsetting the balance between slave states and free states, U.S. President Andrew Jackson refused to push for the annexation of Texas, but in his last official act in office he granted Texas diplomatic recognition.[55] With the United States unwilling to annex Texas, Houston began courting British support; as part of this effort, he urged the end of the importation of slaves into Texas.[56]

In early 1837, the government moved to a new capital, the city of Houston, named after him as the country's first president.[57] In 1838, Houston frequently clashed with Congress over issues such as a treaty with the Cherokee and a land-office act[58] and was forced to put down the Córdova Rebellion, a plot to allow Mexico to reclaim Texas with aid from the Kickapoo Indians.[9] The Texas constitution barred presidents from seeking a second term, so Houston did not stand for re-election in the 1838 election and left office in late 1838. He was succeeded by Mirabeau B. Lamar, who, along with Burnet, led a faction of Texas politicians opposed to Houston.[59] The Lamar administration removed many of Houston's appointees, launched a war against the Cherokee, and established a new capital at Austin, Texas.[60] Meanwhile, Houston opened a legal practice and co-founded a land company with the intent of developing the town of Sabine City.[61] In 1839, he was elected to represent San Augustine County in the Texas House of Representatives.[62]</ref>

Houston defeated Burnet in the 1841 Texas presidential election, winning a large majority of the vote.[63] Houston appointed Anson Jones as secretary of state, Asa Brigham as secretary of the treasury, George Washington Hockley as secretary of war, and George Whitfield Terrell as attorney general.[64] The republic faced a difficult financial situation; at one point, Houston commandeered an American brig used to transport Texas soldiers because the government could not afford to pay the brig's captain.[65] The Santa Fe Expedition and other initiatives pursued by Lamar had stirred tensions with Mexico, and rumors frequently raised fears that Santa Anna would launch an invasion of Texas.[66] Houston continued to curry favor with Britain and France, partly in the hope that British and French influence in Texas would encourage the United States to annex Texas.[67] The Tyler administration made the annexation of Texas its chief foreign policy priority, and in April 1844, Texas and the United States signed an annexation treaty. Annexation did not have sufficient support in Congress, and the United States Senate rejected the treaty in June.[68]

Henry Clay and Martin Van Buren, the respective front-runners for the Whig and Democratic nominations in the 1844 presidential election, both opposed the annexation of Texas. However, Van Buren's opposition to annexation damaged his candidacy, and he was defeated by James K. Polk, an acolyte of Jackson and an old friend of Houston, at the 1844 Democratic National Convention. Polk defeated Clay in the general election, giving backers of annexation an electoral mandate. Meanwhile, Houston's term ended in December 1844, and he was succeeded by Anson Jones, his secretary of state. In the waning days of his own presidency, Tyler used Polk's victory to convince Congress to approve of the annexation of Texas. Seeking Texas's immediate acceptance of annexation, Tyler made Texas a generous offer that allowed the state to retain control of its public lands, though it would be required to keep its public debt.[69] A Texas convention approved of the offer of annexation in July 1845, and Texas officially became the 28th U.S. state on December 29, 1845.[70]

U.S. Senator

Mexican–American War and aftermath (1846–1853)

In February 1846, the Texas legislature elected Houston and Thomas Jefferson Rusk as Texas's two inaugural U.S. senators. Houston chose to align with the Democratic Party, which contained many of his old political allies, including President Polk.[71] As a former president of Texas, Houston is the only former foreign head of state to have served in the U.S. Congress. He was the first person to serve as the governor of a state and then be elected to the U.S. Senate by another state. In 2018, Mitt Romney became the second.[72] William W. Bibb accomplished the same feat in reverse order.

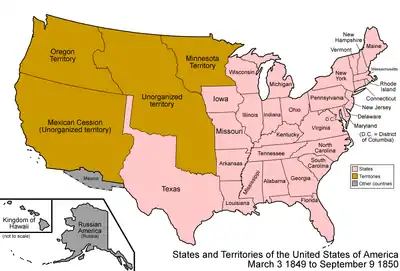

Breaking with the Senate tradition that held that freshman senators were not to address the Senate, Houston strongly advocated in early 1846 for the annexation of Oregon Country. In the Oregon Treaty, reached later in 1846, Britain and the United States agreed to split Oregon Country.[73] Meanwhile, Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to lead a U.S. army to the Rio Grande, which had been set as the Texas-Mexico border under the Treaty of Velasco; Mexico claimed the Nueces River constituted the true border. After a skirmish between Taylor's unit and the Mexican army, the Mexican–American War broke out in April 1846. Houston initially supported Polk's prosecution of the war, but differences between the two men emerged in 1847.[74] After two years of fighting, the United States defeated Mexico and, through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, acquired the Mexican Cession. Mexico also agreed to recognize the Rio Grande as the border between Mexico and Texas.[75]

After the war, disputes over the extension of slavery into the territories raised sectional tensions. Unlike most of his Southern colleagues, Houston voted for the Oregon Bill of 1848, which organized Oregon Territory as a free territory. Defending his vote to create a territory that excluded slavery, Houston stated "I would be the last man to wish to do anything injurious to the South, but I do not think that on all occasions we are justified in agitating [slavery]."[76] He criticized both Northern abolitionists and Democratic followers of Calhoun as extremists who sought to undermine the union.[77] He supported the Compromise of 1850, a sectional compromise on slavery on the territories. Under the compromise, California was admitted as a free state, the slave trade was prohibited in the District of Columbia, a more stringent fugitive slave law was passed, and Utah Territory and New Mexico Territory were established. Texas gave up some of its claims on New Mexico, but it retained El Paso, Texas, and the United States assumed Texas's large public debt.[78] Houston sought the Democratic nomination in the 1852 presidential election, but he was unable to consolidate support outside of his home state. The 1852 Democratic National Convention ultimately nominated Franklin Pierce, a compromise nominee, who went on to win the election.[79]

Pierce and Buchanan administrations (1853–1859)

In 1854, Senator Stephen A. Douglas led the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which organized Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory. The act also repealed the Missouri Compromise, an act that had banned slavery in territories north of parallel 36°30′ north. Houston voted against the act, in part because he believed that Native Americans would lose much of their land as a result of the act. He also perceived that it would lead to increased sectional tensions over slavery.[80] Houston's opposition to the Kansas–Nebraska Act led to his departure from the Democratic Party.[81] In 1855, Houston began to be associated publicly with the American Party, the political wing of the nativist and unionist Know Nothing movement.[82] The Whig Party had collapsed after the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and the Know Nothings and the anti-slavery Republican Party had both emerged as major political movements.[83] Houston's affiliation with the party stemmed in part from his fear of the growing influence of Catholic voters; though he opposed barring Catholics from holding office, he wanted to extend the naturalization period for immigrants to 21 years.[84] He was attracted to the Know Nothing's support for a Native American state as well the party's unionist stance.[85]

Houston sought the presidential nomination at the Know Nothing party's 1856 national convention, but the party nominated former President Millard Fillmore. Houston was disappointed by Fillmore's selection as well as the party platform, which did not rebuke the Kansas–Nebraska Act, but he eventually decided to support Fillmore's candidacy. Despite Houston's renewed support, the American Party split over slavery, and Democrat James Buchanan won the 1856 presidential election. The American Party collapsed after the election, and Houston did not affiliate with a national political party for the remainder of his tenure in the senate.[86] In the 1857 Texas gubernatorial election, Texas Democrats nominated Hardin Richard Runnels, who supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act and attacked Houston's record. In response, Houston announced his own candidacy for governor, but Runnels defeated him by a decisive margin.[87] It was the only electoral defeat of his career.[88] After the gubernatorial election, the Texas legislature denied Houston re-election in the senate; Houston rejected calls to resign immediately and served until the end of his term in early 1859.[89]

Governor of Texas

Houston ran against Runnels in the 1859 gubernatorial election. Capitalizing on Runnels's unpopularity over state issues such as Native American raids, Houston won the election and took office in December 1859.[90] In the 1860 presidential election, Houston and John Bell were the two major contenders for the presidential nomination of the newly formed Constitutional Union Party, which consisted largely of Southern unionists. Houston narrowly trailed Bell on the first ballot of the 1860 Constitutional Union Convention, but Bell clinched the nomination on the second ballot.[91] Nonetheless, some of Houston's Texan supporters nominated him for president in April 1860. Other backers attempted to launch a nationwide campaign, but in August 1860, Houston announced that he would not be a candidate for president. He refused to endorse any of the remaining presidential candidates.[92] In late 1860, Houston campaigned across his home state, calling on Texans to resist those who advocated for secession if Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election.[93]

After Lincoln won the November 1860 presidential election, several Southern states seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America.[94] A Texas political convention voted to secede from the United States on February 1, 1861, and Houston proclaimed that Texas was once again an independent republic, but he refused to recognize that same convention's authority to join Texas to the Confederacy. After Houston refused to swear an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy, the legislature declared the governorship vacant. Houston did not recognize the validity of his removal, but he did not attempt to use force to remain in office, and he refused aid from the federal government to prevent his removal. His successor, Edward Clark, was sworn in on March 18.[95] In an undelivered speech, Houston wrote:

Fellow-Citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by the Convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the Constitution of Texas, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies, I refuse to take this oath. I deny the power of this Convention to speak for Texas. ... I protest. ... against all the acts and doings of this convention and I declare them null and void.[96]

On April 19, 1861, he told a crowd:

Let me tell you what is coming. After the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, you may win Southern independence if God be not against you, but I doubt it. I tell you that, while I believe with you in the doctrine of states rights, the North is determined to preserve this Union. They are not a fiery, impulsive people as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche; and what I fear is, they will overwhelm the South.[97]

According to historian Randolph Campbell:

- Houston did everything possible to prevent secession and war, but his first loyalty was to Texas—and the South. Houston refused offers of troops from the United States to keep Texas in the Union and announced on May 10, 1861 that he would stand with the Confederacy in its war effort.[88]

Retirement and death

After leaving office, Houston returned to his home in Galveston.[98] He later settled in Huntsville, Texas, where he lived in a structure known as the Steamboat House. In the midst of the Civil War, Houston was shunned by many Texas leaders, though he continued to correspond with Confederate officer Ashbel Smith and Texas governor Francis Lubbock. His son, Sam Houston, Jr., served in the Confederate army during the Civil War, but returned home after being wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.[99] Houston's health suffered a precipitous decline in April 1863, and he died on July 26, 1863, at 70 years of age.[100]

The inscription on Houston's tomb reads:

A Brave Soldier. A Fearless Statesman.

A Great Orator—A Pure Patriot.

A Faithful Friend, A Loyal Citizen.

A Devoted Husband and Father.

A Consistent Christian—An Honest Man.

Personal life

In January 1829 Houston, then Governor of Tennessee, married 19-year-old Eliza Allen. The marriage lasted 11 weeks. Neither Houston nor Eliza ever gave a reason for their separation, but Eliza refused to sanction divorce. Subsequently, he resigned his governorship and went to live with his Cherokee family for three years.[9][17] In the summer of 1830, Houston married Tiana Rogers (sometimes called Diana), daughter of Chief John "Hellfire" Rogers (1740–1833), a Scots-Irish trader, and Jennie Due (1764–1806), a sister of Chief John Jolly, in a Cherokee ceremony. The ceremony was modest since it was Tiana's second marriage; she was widowed with two children from her previous marriage: Gabriel, born 1819, and Joanna, born 1822. She and Houston first met when she was ten years old, and he was stunned to see how beautiful she was when he returned to her village years later. The two lived together for several years. Tennessee society disapproved of the marriage because under civil law, he was still legally married to Eliza Allen Houston. After declining to accompany Houston to Texas in 1832, Tiana later remarried. She died in 1838 of pneumonia.[101] Will Rogers was her nephew, three generations removed.[102]

In 1837, after becoming President of the Republic of Texas, he was able to acquire, from a district court judge, a divorce from Eliza Allen.[103]

In 1839, he purchased a horse which became one of the foundation sires of the American Quarter Horse breed named Copperbottom. He owned the horse until its death in 1860.[104][105][106]

On May 9, 1840, Houston, aged 47, married for a third time. His bride was 21-year-old Margaret Moffette Lea of Marion, Alabama, the daughter of planters. They had eight children. Margaret acted as a tempering influence on her much older husband and convinced him to stop drinking. Although the Houstons had numerous houses, they kept only one continuously: Cedar Point (1840–1863) on Trinity Bay.

In 1833, Houston was baptized into the Catholic faith in order to qualify under the existing Mexican law for property ownership in Coahuila y Tejas. The sacrament was held in the living room of the Adolphus Sterne House in Nacogdoches, Texas.[107] By 1854, Margaret had spent 14 years trying to convert Houston to the Baptist church. With the assistance of George Washington Baines, she convinced Houston to convert, and he agreed to adult baptism. Spectators from neighboring communities came to Independence, Texas, to witness the event. On November 19, 1854, Houston was baptized by Rev. Rufus C. Burleson, president of Baylor University, by immersion in Little Rocky Creek, two miles southeast of Independence.[108][109]

Relationship to slavery

Houston was born on and inherited a slave plantation and mansion, and had many slaves throughout his life.[110] While he didn't enforce some anti-slavery measures, strong slavery laws were still in place under his leadership. He did not support the westward expansion of slavery.[111] His attitude towards slavery was of pragmatism. He was a centrist who thought that both sides of the slavery debate were too extreme on the issue, and his greatest focus was not splitting up the Union. He thought states should decide for themselves on the issue of slavery.

Legacy

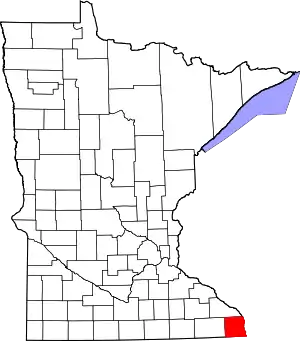

Houston, the largest city in Texas and the American South, is named in his honor. Several other things and places are named for Houston, including Sam Houston State University; Houston County, Minnesota; Houston County, Tennessee; Houston County, Texas. Other monuments and memorials include Sam Houston National Forest, Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center, U.S. Army post Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, the USS Sam Houston (SSBN-609), and a sculpture of Houston in the city of Houston's Hermann Park. In addition, a 67-foot-tall statue of Houston, created by sculptor David Adickes, named A Tribute to Courage (and colloquially called "Big Sam") stands next to I-45, between Dallas and Houston, in Huntsville, Texas. Along with Stephen F. Austin, Houston is one of two Texans with a statue in the National Statuary Hall. Houston has been portrayed in works such as Man of Conquest, Gone to Texas, Texas Rising, and The Alamo. In 1960, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[112]

There is a question about whether Houston made a pejorative comment about Mexicans in an 1835 speech to the Texas volunteer army at Refugio. One second hand source makes this claim;[113] however, subsequent research casts doubt on the source and concludes that the disparaging comment is unlikely to have occurred.[114][115]

Notes

- Houston descended from Sir John Houston, who in the late 1600s built the Houston baronial estate near Johnstone, Scotland. From him came John Houston and Margaret Mary (nee Cunningham) Houston, who lived for some time in Ireland and in 1735 they immigrated to America, ending up in on their Timber Ridge plantation.[4]

- Houston's uncle, the Presbyterian Rev. Samuel Houston, was an elected member of the "lost" State of Franklin then in the western frontier of North Carolina, who advocated for the passage of his proposed "A Declaration of Rights or Form of Government on the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Frankland" at the convention that was assembled in Greeneville, Tennessee on November 14, 1785. Rev. Houston returned to Rockbridge County, Virginia after the assembled State of Franklin convention rejected his constitutional proposal.[5]

- After the Houstons migrated west to Tennessee, Timber Ridge was razed and Church Hill was built on the site.[7]

- Another Texan force had been defeated at the Battle of Coleto; the Texans captured in that battle were subsequently massacred by order of Santa Anna.[46]

- After Austin died of an illness in December 1836, Houston ordered a month of mourning.[53]

References

- "Sam Houston | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Williams 1994, pp. 13–18.

- Haley 2002, p. 5.

- Haley 2002, pp. 4–5.

- Dr. J. G. M. Ramsey Autobiography and Letters, p. 317. Edited by William B. Hesseltine. The University of Tennessee Press.

- Houston, Sam (1996). The Personal Correspondence of Sam Houston: 1839-1845. University of North Texas Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-57441-000-6.

- Haley 2002, p. 7.

- Williams 1994, pp. 21–24.

- Samuel Houston from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Haley 2002, p. 6.

- Haley 2002, pp. 7–11.

- "History of Hiwassee Island" (PDF). The Center for Historic Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- Williams 1994, pp. 25–26.

- Haley 2002, p. 8.

- Haley 2002, p. 10.

- Haley 2002, pp. 7–8.

- Sam Houston Papers #37, The Texas Collection, Baylor University.

- Haley 2002, pp. 11–14.

- Haley 2002, pp. 15–17.

- Haley 2002, pp. 19–20.

- Haley 2002, pp. 24–25.

- Haley 2002, pp. 26–29.

- Haley 2002, pp. 31–33.

- Haley 2002, pp. 34–35.

- Haley 2002, pp. 38–39.

- Haley 2002, pp. 40–41.

- Haley 2002, pp. 45–46.

- Haley 2002, pp. 47–49.

- Haley 2002, pp. 49–57.

- Haley 2002, pp. 60–61.

- Haley 2002, pp. 64–65.

- Haley 2002, pp. 68–69.

- Haley 2002, pp. 71–72.

- Haley 2002, pp. 73–74.

- Haley 2002, pp. 80–82.

- Alfred Mason Williams (1893). Sam Houston and the War of Independence in Texas. Houghton, Mifflin. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-7222-9291-4.

- Haley 2002, pp. 87–88.

- Haley 2002, pp. 91–92.

- Haley 2002, pp. 96–97.

- Haley 2002, pp. 99–100.

- Haley 2002, pp. 109–113.

- Haley 2002, pp. 113–118.

- Haley 2002, pp. 121–124.

- Haley 2002, pp. 125–128.

- Haley 2002, pp. 128–129.

- Haley 2002, p. 129.

- Haley 2002, pp. 144–147, 158.

- Haley 2002, pp. 147–151.

- Haley 2002, pp. 153–154.

- "Sam Houston | TSLAC". www.tsl.texas.gov. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Haley 2002, pp. 163–165.

- Haley 2002, pp. 166–169.

- Haley 2002, pp. 175–176.

- Haley 2002, pp. 171–172.

- Haley 2002, pp. 175, 190.

- Haley 2002, pp. 189–190.

- Haley 2002, p. 186.

- Haley 2002, pp. 201–202.

- Haley 2002, pp. 205–206.

- Haley 2002, pp. 213–215.

- Haley 2002, pp. 210–211.

- Roberts 1993, pp. 23–25, 38.

- Haley 2002, pp. 226–227.

- Haley 2002, pp. 233–236.

- Haley 2002, pp. 245–246.

- Haley 2002, pp. 238–242.

- Haley 2002, pp. 262–263.

- Haley 2002, pp. 279–281, 286.

- Haley 2002, pp. 285–287.

- "Annexation Process: 1836-1845 a Summary Timeline | TSLAC".

- Haley 2002, pp. 294–295.

- "Mitt Romney Prepares for Unusual US Senate Bid | Smart Politics". editions.lib.umn.edu. September 14, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- Haley 2002, p. 297.

- Haley 2002, pp. 297–298.

- "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo". HISTORY. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- Haley 2002, p. 301.

- Haley 2002, pp. 302–304.

- Haley 2002, pp. 304–308.

- Haley 2002, pp. 311–313.

- Haley 2002, pp. 321–326.

- Cantrell 1993, p. 333.

- Cantrell 1993, pp. 328–330.

- Haley 2002, pp. 340–341.

- Cantrell 1993, pp. 330–333.

- Haley 2002, pp. 341–342.

- Cantrell 1993, pp. 340–342.

- Haley 2002, pp. 344, 352.

- Campbell 2000.

- Haley 2002, pp. 353, 360.

- Haley 2002, pp. 362–365.

- Haley 2002, pp. 371–372.

- Haley 2002, pp. 372–374.

- Haley 2002, pp. 380–382.

- Haley 2002, pp. 383–384.

- Westwood 1984, pp. 128–129, 133–134.

- Haley 2002, pp. 390–391.

- Haley 2002, p. 397.

- Westwood 1984, p. 129.

- Haley 2002, pp. 399–405.

- Haley 2002, pp. 412–415.

- Haley 2002, p. 70.

- James 1988, pp. 150–152.

- "Sam Houston and Eliza Allen: "Ten Thousand Imputed Slanders"". The Tennessee Historical Society. September 12, 2018. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- "History of the Quarter Horse - AQHA". www.aqha.com.

- "Copperbottom: A Lost Bloodline". Archived from the original on October 28, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- "Copperbottom" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- Haley 2002, pp. 104–105.

- Augustin, Byron; Pitts, William L. "Independence, Texas". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- Seale 1992, pp. 167–171.

- Krystyniak, Frank. "Houston, the Emancipator – Today@Sam – Sam Houston State University". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- Kreneck, Thomas H. "Houston, Sam". Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- De León, Arnoldo (January 1, 1983). They Called Them Greasers: Anglo Attitudes toward Mexicans in Texas, 1821–1900 (1 ed.). University of Texas Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0292780545. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- Crisp, James E. (February 24, 2005). Sleuthing the Alamo: Davy Crockett's Last Stand and Other Mysteries of the Texas Revolution (New Narratives in American History) (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195163506.

- "Analysis of Sleuthing the Alamo - 980 Words | Bartleby".

Bibliography

| External video | |

|---|---|

Works cited

- Campbell, Randolph B (2000), "Houston, Sam", American National Biography, doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.0400528

- Cantrell, Gregg (1993). "Sam Houston and the Know-Nothings: A Reappraisal". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 96 (3): 327–343. JSTOR 30237138.

- Haley, James L. (2002). Sam Houston. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3644-8.

- Roberts, Madge Thornall (1993). Star of Destiny: The Private Life of Sam and Margaret Houston. Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press. ISBN 0-929398-51-3. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- Seale, William (April 1992). Sam Houston's Wife: A Biography of Margaret Lea Houston. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2436-0.

- Westwood, Howard C. (1984). "President Lincoln's Overture to Sam Houston". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 88 (2): 125–144. JSTOR 30239858.

- Williams, John H. (1994) [1993]. Sam Houston: Life and Times of Liberator of Texas an Authentic American Hero. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780671880712.

Further reading

- Brinkley, William. The Texas Revolution Texas A&M Press: ISBN 0-87611-041-3.

- Crook, Elizabeth (1990). "Sam Houston and Eliza Allen: The Marriage and the Mystery". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 94 (1): 1–36. JSTOR 30237054.

- Sword of San Jacinto, DeBruhl, Marshall; Random House: ISBN 0-394-57623-3.

- Flanagan, Sue (June 28, 2010). Sam Houston's Texas. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78921-0.

- Hunt, Lenoir (1992). My Master, The Inside Story of Sam Houston and His Times, By His Former Slave Jeff Hamilton. State House Press. ISBN 978-1-933337-23-4.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay. "The Texas War Of 1835-1836." History Today (Feb 1960) 10#2 pp 116–123.

- James, Marquis (1988) [1929]. The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292770409..

- MacKinnon, William P. (2013). "Into the Fray: Sam Houston's Utah War". Journal of Mormon History. 39 (3): 198–243. doi:10.2307/24243857. JSTOR 24243857. S2CID 254486356.

- The Eagle and the Raven; Michener, James A.; State House Press: ISBN 0-938349-57-0.

- Haley, James L. (2015). Sam Houston. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ASIN B00VY161EI.

- O'Neal, Bill (2016). Sam Houston: A Study in Leadership. Eakin Press. ISBN 9781681790374.

- Rozelle, Ron (2017). Exiled: The Last Days of Sam Houston. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781623495879.

External links

- United States Congress. "Sam Houston (id: H000827)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

| Library resources about Sam Houston |

| By Sam Houston |

|---|

- Sam Houston papers (Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, Houston, Texas)

- Life of General Houston, 1793–1863 published 1891, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Samuel Houston from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Sam Houston Memorial Museum in Huntsville, Texas

- Sam Houston Historic Schoolhouse in Maryville, Tennessee

- Documentary film Sam Houston: American Statesman, Soldier, and Pioneer. Archived March 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine 2009, The Sam Houston Project.

- Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture entry

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Papers of Governor Sam Houston, 1827–1829

- Sam Houston Rode a Gray Horse

- Houston Family Papers, 1836–1869 and undated, in the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library at Texas Tech University

- Life and select literary remains of Sam Houston of Texas published 1884

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)