Geographic information system

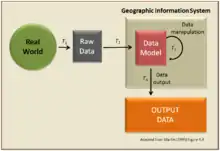

A geographic information system (GIS) consists of integrated computer hardware and software that store, manage, analyze, edit, output, and visualize geographic data.[1][2] Much of this often happens within a spatial database, however, this is not essential to meet the definition of a GIS.[1] In a broader sense, one may consider such a system also to include human users and support staff, procedures and workflows, the body of knowledge of relevant concepts and methods, and institutional organizations.

The uncounted plural, geographic information systems, also abbreviated GIS, is the most common term for the industry and profession concerned with these systems. It is roughly synonymous with geoinformatics. The academic discipline that studies these systems and their underlying geographic principles, may also be abbreviated as GIS, but the unambiguous GIScience is more common.[3] GIScience is often considered a subdiscipline of geography within the branch of technical geography.

Geographic information systems are utilized in multiple technologies, processes, techniques and methods. They are attached to various operations and numerous applications, that relate to: engineering, planning, management, transport/logistics, insurance, telecommunications, and business.[4] For this reason, GIS and location intelligence applications are at the foundation of location-enabled services, which rely on geographic analysis and visualization.

GIS provides the capability to relate previously unrelated information, through the use of location as the "key index variable". Locations and extents that are found in the Earth's spacetime are able to be recorded through the date and time of occurrence, along with x, y, and z coordinates; representing, longitude (x), latitude (y), and elevation (z). All Earth-based, spatial–temporal, location and extent references should be relatable to one another, and ultimately, to a "real" physical location or extent. This key characteristic of GIS has begun to open new avenues of scientific inquiry and studies.

History and development

While digital GIS dates to the mid-1960s, when Roger Tomlinson first coined the phrase "geographic information system",[5] many of the geographic concepts and methods that GIS automates date back decades earlier.

One of the first known instances in which spatial analysis was used came from the field of epidemiology in the "Rapport sur la marche et les effets du choléra dans Paris et le département de la Seine" (1832).[6] French geographer and cartographer, Charles Picquet created a map outlining the forty-eight Districts in Paris, using halftone color gradients, to provide a visual representation for the number of reported deaths due to cholera per every 1,000 inhabitants.

In 1854, John Snow, an epidemiologist and physician, was able to determine the source of a cholera outbreak in London through the use of spatial analysis. Snow achieved this through plotting the residence of each casualty on a map of the area, as well as the nearby water sources. Once these points were marked, he was able to identify the water source within the cluster that was responsible for the outbreak. This was one of the earliest successful uses of a geographic methodology in pinpointing the source of an outbreak in epidemiology. While the basic elements of topography and theme existed previously in cartography, Snow's map was unique due to his use of cartographic methods, not only to depict, but also to analyze clusters of geographically dependent phenomena.

The early 20th century saw the development of photozincography, which allowed maps to be split into layers, for example one layer for vegetation and another for water. This was particularly used for printing contours – drawing these was a labour-intensive task but having them on a separate layer meant they could be worked on without the other layers to confuse the draughtsman. This work was initially drawn on glass plates, but later plastic film was introduced, with the advantages of being lighter, using less storage space and being less brittle, among others. When all the layers were finished, they were combined into one image using a large process camera. Once color printing came in, the layers idea was also used for creating separate printing plates for each color. While the use of layers much later became one of the typical features of a contemporary GIS, the photographic process just described is not considered a GIS in itself -– as the maps were just images with no database to link them to.

Two additional developments are notable in the early days of GIS: Ian McHarg's publication "Design with Nature"[7] and its map overlay method and the introduction of a street network into the U.S. Census Bureau's DIME (Dual Independent Map Encoding) system.[8]

The first publication detailing the use of computers to facilitate cartography was written by Waldo Tobler in 1959.[9] Further computer hardware development spurred by nuclear weapon research led to more widespread general-purpose computer "mapping" applications by the early 1960s.[10]

In 1960 the world's first true operational GIS was developed in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, by the federal Department of Forestry and Rural Development. Developed by Roger Tomlinson, it was called the Canada Geographic Information System (CGIS) and was used to store, analyze, and manipulate data collected for the Canada Land Inventory, an effort to determine the land capability for rural Canada by mapping information about soils, agriculture, recreation, wildlife, waterfowl, forestry and land use at a scale of 1:50,000. A rating classification factor was also added to permit analysis.[11][12]

CGIS was an improvement over "computer mapping" applications as it provided capabilities for data storage, overlay, measurement, and digitizing/scanning. It supported a national coordinate system that spanned the continent, coded lines as arcs having a true embedded topology and it stored the attribute and locational information in separate files. As a result of this, Tomlinson has become known as the "father of GIS", particularly for his use of overlays in promoting the spatial analysis of convergent geographic data.[13] CGIS lasted into the 1990s and built a large digital land resource database in Canada. It was developed as a mainframe-based system in support of federal and provincial resource planning and management. Its strength was continent-wide analysis of complex datasets. The CGIS was never available commercially.

In 1964 Howard T. Fisher formed the Laboratory for Computer Graphics and Spatial Analysis at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (LCGSA 1965–1991), where a number of important theoretical concepts in spatial data handling were developed, and which by the 1970s had distributed seminal software code and systems, such as SYMAP, GRID, and ODYSSEY, to universities, research centers and corporations worldwide.[14] These programs were the first examples of general purpose GIS software that was not developed for a particular installation, and was very influential on future commercial software, such as Esri ARC/INFO, released in 1983.

By the late 1970s two public domain GIS systems (MOSS and GRASS GIS) were in development, and by the early 1980s, M&S Computing (later Intergraph) along with Bentley Systems Incorporated for the CAD platform, Environmental Systems Research Institute (ESRI), CARIS (Computer Aided Resource Information System), and ERDAS (Earth Resource Data Analysis System) emerged as commercial vendors of GIS software, successfully incorporating many of the CGIS features, combining the first generation approach to separation of spatial and attribute information with a second generation approach to organizing attribute data into database structures.[15]

In 1986, Mapping Display and Analysis System (MIDAS), the first desktop GIS product[16] was released for the DOS operating system. This was renamed in 1990 to MapInfo for Windows when it was ported to the Microsoft Windows platform. This began the process of moving GIS from the research department into the business environment.

By the end of the 20th century, the rapid growth in various systems had been consolidated and standardized on relatively few platforms and users were beginning to explore viewing GIS data over the Internet, requiring data format and transfer standards. More recently, a growing number of free, open-source GIS packages run on a range of operating systems and can be customized to perform specific tasks. The major trend of the 21st Century has been the integration of GIS capabilities with other Information technology and Internet infrastructure, such as relational databases, cloud computing, software as a service (SAAS), and mobile computing.[17]

GIS software

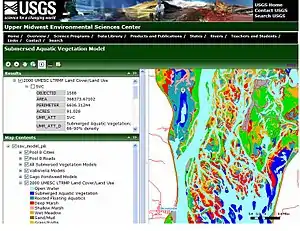

The distinction must be made between a singular geographic information system, which is a single installation of software and data for a particular use, along with associated hardware, staff, and institutions (e.g., the GIS for a particular city government); and GIS software, a general-purpose application program that is intended to be used in many individual geographic information systems in a variety of application domains.[18]: 16 Starting in the late 1970s, many software packages have been created specifically for GIS applications. Esri's ArcGIS, which includes ArcGIS Pro and the legacy software ArcMap, currently dominate the GIS Market. Other examples of GIS include Autodesk and MapInfo Professional and open source programs such as QGIS, GRASS GIS, MapGuide, and Hadoop-GIS.[19] These and other desktop GIS applications include a full suite of capabilities for entering, managing, analyzing, and visualizing geographic data, and are designed to be used on their own.

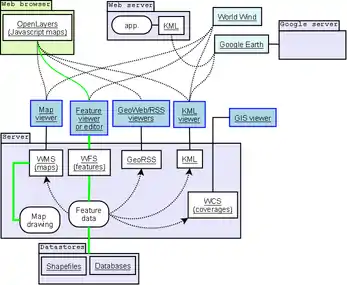

Starting in the late 1990s with the emergence of the Internet, as computer network technology progressed, GIS infrastructure and data began to move to servers, providing another mechanism for providing GIS capabilities.[20]: 216 This was facilitated by standalone software installed on a server, similar to other server software such as HTTP servers and relational database management systems, enabling clients to have access to GIS data and processing tools without having to install specialized desktop software. These networks are known as distributed GIS.[21][22] This strategy has been extended through the Internet and development of cloud-based GIS platforms such as ArcGIS Online and GIS-specialized software as a service (SAAS). The use of the Internet to facilitate distributed GIS is known as Internet GIS.[21][22]

An alternative approach is the integration of some or all of these capabilities into other software or information technology architectures. One example is a spatial extension to Object-relational database software, which defines a geometry datatype so that spatial data can be stored in relational tables, and extensions to SQL for spatial analysis operations such as overlay. Another example is the proliferation of geospatial libraries and application programming interfaces (e.g., GDAL, Leaflet, D3.js) that extend programming languages to enable the incorporation of GIS data and processing into custom software, including web mapping sites and location-based services in smartphones.

Geospatial data management

The core of any GIS is a database that contains representations of geographic phenomena, modeling their geometry (location and shape) and their properties or attributes. A GIS database may be stored in a variety of forms, such as a collection of separate data files or a single spatially-enabled relational database. Collecting and managing these data usually constitutes the bulk of the time and financial resources of a project, far more than other aspects such as analysis and mapping.[20]: 175

Aspects of geographic data

GIS uses spatio-temporal (space-time) location as the key index variable for all other information. Just as a relational database containing text or numbers can relate many different tables using common key index variables, GIS can relate otherwise unrelated information by using location as the key index variable. The key is the location and/or extent in space-time.

Any variable that can be located spatially, and increasingly also temporally, can be referenced using a GIS. Locations or extents in Earth space–time may be recorded as dates/times of occurrence, and x, y, and z coordinates representing, longitude, latitude, and elevation, respectively. These GIS coordinates may represent other quantified systems of temporo-spatial reference (for example, film frame number, stream gage station, highway mile-marker, surveyor benchmark, building address, street intersection, entrance gate, water depth sounding, POS or CAD drawing origin/units). Units applied to recorded temporal-spatial data can vary widely (even when using exactly the same data, see map projections), but all Earth-based spatial–temporal location and extent references should, ideally, be relatable to one another and ultimately to a "real" physical location or extent in space–time.

Related by accurate spatial information, an incredible variety of real-world and projected past or future data can be analyzed, interpreted and represented.[23] This key characteristic of GIS has begun to open new avenues of scientific inquiry into behaviors and patterns of real-world information that previously had not been systematically correlated.

Data modeling

GIS data represents phenomena that exist in the real world, such as roads, land use, elevation, trees, waterways, and states. The most common types of phenomena that are represented in data can be divided into two conceptualizations: discrete objects (e.g., a house, a road) and continuous fields (e.g., rainfall amount or population density).[20] : 62–65 Other types of geographic phenomena, such as events (e.g., location of World War II battles), processes (e.g., extent of suburbanization), and masses (e.g., types of soil in an area) are represented less commonly or indirectly, or are modeled in analysis procedures rather than data.

Traditionally, there are two broad methods used to store data in a GIS for both kinds of abstractions mapping references: raster images and vector. Points, lines, and polygons represent vector data of mapped location attribute references.

A new hybrid method of storing data is that of identifying point clouds, which combine three-dimensional points with RGB information at each point, returning a "3D color image". GIS thematic maps then are becoming more and more realistically visually descriptive of what they set out to show or determine.

Data acquisition

GIS data acquisition includes several methods for gathering spatial data into a GIS database, which can be grouped into three categories: primary data capture, the direct measurement phenomena in the field (e.g., remote sensing, the global positioning system); secondary data capture, the extraction of information from existing sources that are not in a GIS form, such as paper maps, through digitization; and data transfer, the copying of existing GIS data from external sources such as government agencies and private companies. All of these methods can consume significant time, finances, and other resources.[20]: 173

Primary data capture

Survey data can be directly entered into a GIS from digital data collection systems on survey instruments using a technique called coordinate geometry (COGO). Positions from a global navigation satellite system (GNSS) like Global Positioning System can also be collected and then imported into a GIS. A current trend in data collection gives users the ability to utilize field computers with the ability to edit live data using wireless connections or disconnected editing sessions.[24] Current trend is to utilize applications available on smartphones and PDAs - Mobile GIS.[25] This has been enhanced by the availability of low-cost mapping-grade GPS units with decimeter accuracy in real time. This eliminates the need to post process, import, and update the data in the office after fieldwork has been collected. This includes the ability to incorporate positions collected using a laser rangefinder. New technologies also allow users to create maps as well as analysis directly in the field, making projects more efficient and mapping more accurate.

Remotely sensed data also plays an important role in data collection and consist of sensors attached to a platform. Sensors include cameras, digital scanners and lidar, while platforms usually consist of aircraft and satellites. In England in the mid 1990s, hybrid kite/balloons called helikites first pioneered the use of compact airborne digital cameras as airborne geo-information systems. Aircraft measurement software, accurate to 0.4 mm was used to link the photographs and measure the ground. Helikites are inexpensive and gather more accurate data than aircraft. Helikites can be used over roads, railways and towns where unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are banned.

Recently aerial data collection has become more accessible with miniature UAVs and drones. For example, the Aeryon Scout was used to map a 50-acre area with a ground sample distance of 1 inch (2.54 cm) in only 12 minutes.[26]

The majority of digital data currently comes from photo interpretation of aerial photographs. Soft-copy workstations are used to digitize features directly from stereo pairs of digital photographs. These systems allow data to be captured in two and three dimensions, with elevations measured directly from a stereo pair using principles of photogrammetry. Analog aerial photos must be scanned before being entered into a soft-copy system, for high-quality digital cameras this step is skipped.

Satellite remote sensing provides another important source of spatial data. Here satellites use different sensor packages to passively measure the reflectance from parts of the electromagnetic spectrum or radio waves that were sent out from an active sensor such as radar. Remote sensing collects raster data that can be further processed using different bands to identify objects and classes of interest, such as land cover.

Secondary data capture

The most common method of data creation is digitization, where a hard copy map or survey plan is transferred into a digital medium through the use of a CAD program, and geo-referencing capabilities. With the wide availability of ortho-rectified imagery (from satellites, aircraft, Helikites and UAVs), heads-up digitizing is becoming the main avenue through which geographic data is extracted. Heads-up digitizing involves the tracing of geographic data directly on top of the aerial imagery instead of by the traditional method of tracing the geographic form on a separate digitizing tablet (heads-down digitizing). Heads-down digitizing, or manual digitizing, uses a special magnetic pen, or stylus, that feeds information into a computer to create an identical, digital map. Some tablets use a mouse-like tool, called a puck, instead of a stylus.[27][28] The puck has a small window with cross-hairs which allows for greater precision and pinpointing map features. Though heads-up digitizing is more commonly used, heads-down digitizing is still useful for digitizing maps of poor quality.[28]

Existing data printed on paper or PET film maps can be digitized or scanned to produce digital data. A digitizer produces vector data as an operator traces points, lines, and polygon boundaries from a map. Scanning a map results in raster data that could be further processed to produce vector data.

When data is captured, the user should consider if the data should be captured with either a relative accuracy or absolute accuracy, since this could not only influence how information will be interpreted but also the cost of data capture.

After entering data into a GIS, the data usually requires editing, to remove errors, or further processing. For vector data it must be made "topologically correct" before it can be used for some advanced analysis. For example, in a road network, lines must connect with nodes at an intersection. Errors such as undershoots and overshoots must also be removed. For scanned maps, blemishes on the source map may need to be removed from the resulting raster. For example, a fleck of dirt might connect two lines that should not be connected.

Projections, coordinate systems, and registration

The earth can be represented by various models, each of which may provide a different set of coordinates (e.g., latitude, longitude, elevation) for any given point on the Earth's surface. The simplest model is to assume the earth is a perfect sphere. As more measurements of the earth have accumulated, the models of the earth have become more sophisticated and more accurate. In fact, there are models called datums that apply to different areas of the earth to provide increased accuracy, like North American Datum of 1983 for U.S. measurements, and the World Geodetic System for worldwide measurements.

The latitude and longitude on a map made against a local datum may not be the same as one obtained from a GPS receiver. Converting coordinates from one datum to another requires a datum transformation such as a Helmert transformation, although in certain situations a simple translation may be sufficient.[29]

In popular GIS software, data projected in latitude/longitude is often represented as a Geographic coordinate system. For example, data in latitude/longitude if the datum is the 'North American Datum of 1983' is denoted by 'GCS North American 1983'.

Data quality

While no digital model can be a perfect representation of the real world, it is important that GIS data be of a high quality. In keeping with the principle of homomorphism, the data must be close enough to reality so that the results of GIS procedures correctly correspond to the results of real world processes. This means that there is no single standard for data quality, because the necessary degree of quality depends on the scale and purpose of the tasks for which it is to be used. Several elements of data quality are important to GIS data:

- Accuracy

- The degree of similarity between a represented measurement and the actual value; conversely, error is the amount of difference between them.[18]: 623 In GIS data, there is concern for accuracy in representations of location (positional accuracy), property (attribute accuracy), and time. For example, the US 2020 Census says that the population of Houston on April 1, 2020 was 2,304,580; if it was actually 2,310,674, this would be an error and thus a lack of attribute accuracy.

- Precision

- The degree of refinement in a represented value. In a quantitative property, this is the number of significant digits in the measured value.[20]: 115 An imprecise value is vague or ambiguous, including a range of possible values. For example, if one were to say that the population of Houston on April 1, 2020 was "about 2.3 million," this statement would be imprecise, but likely accurate because the correct value (and many incorrect values) are included. As with accuracy, representations of location, property, and time can all be more or less precise. Resolution is a commonly used expression of positional precision, especially in raster data sets.

- Uncertainty

- A general acknowledgement of the presence of error and imprecision in geographic data.[20]: 99 That is, it is a degree of general doubt, given that it is difficult to know exactly how much error is present in a data set, although some form of estimate may be attempted (a confidence interval being such an estimate of uncertainty). This is sometimes used as a collective term for all or most aspects of data quality.

- Vagueness or fuzziness

- The degree to which an aspect (location, property, or time) of a phenomenon is inherently imprecise, rather than the imprecision being in a measured value.[20]: 103 For example, the spatial extent of the Houston metropolitan area is vague, as there are places on the outskirts of the city that are less connected to the central city (measured by activities such as commuting) than places that are closer. Mathematical tools such as fuzzy set theory are commonly used to manage vagueness in geographic data.

- Completeness

- The degree to which a data set represents all of the actual features that it purports to include.[18]: 623 For example, if a layer of "roads in Houston" is missing some actual streets, it is incomplete.

- Currency

- The most recent point in time at which a data set claims to be an accurate representation of reality. This is a concern for the majority of GIS applications, which attempt to represent the world "at present," in which case older data is of lower quality.

- Consistency

- The degree to which the representations of the many phenomena in a data set correctly correspond with each other.[18]: 623 Consistency in topological relationships between spatial objects is an especially important aspect of consistency.[30]: 117 For example, if all of the lines in a street network were accidentally moved 10 meters to the East, they would be inaccurate but still consistent, because they would still properly connect at each intersection, and network analysis tools such as shortest path would still give correct results.

- Propagation of uncertainty

- The degree to which the quality of the results of Spatial analysis methods and other processing tools derives from the quality of input data.[30]: 118 For example, interpolation is a common operation used in many ways in GIS; because it generates estimates of values between known measurements, the results will always be more precise, but less certain (as each estimate has an unknown amount of error).

GIS accuracy depends upon source data, and how it is encoded to be data referenced. Land surveyors have been able to provide a high level of positional accuracy utilizing the GPS-derived positions.[31] High-resolution digital terrain and aerial imagery,[32] powerful computers and Web technology are changing the quality, utility, and expectations of GIS to serve society on a grand scale, but nevertheless there are other source data that affect overall GIS accuracy like paper maps, though these may be of limited use in achieving the desired accuracy.

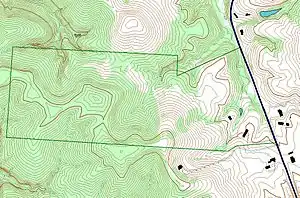

In developing a digital topographic database for a GIS, topographical maps are the main source, and aerial photography and satellite imagery are extra sources for collecting data and identifying attributes which can be mapped in layers over a location facsimile of scale. The scale of a map and geographical rendering area representation type, or map projection, are very important aspects since the information content depends mainly on the scale set and resulting locatability of the map's representations. In order to digitize a map, the map has to be checked within theoretical dimensions, then scanned into a raster format, and resulting raster data has to be given a theoretical dimension by a rubber sheeting/warping technology process known as georeferencing.

A quantitative analysis of maps brings accuracy issues into focus. The electronic and other equipment used to make measurements for GIS is far more precise than the machines of conventional map analysis. All geographical data are inherently inaccurate, and these inaccuracies will propagate through GIS operations in ways that are difficult to predict.[33]

Raster-to-vector translation

Data restructuring can be performed by a GIS to convert data into different formats. For example, a GIS may be used to convert a satellite image map to a vector structure by generating lines around all cells with the same classification, while determining the cell spatial relationships, such as adjacency or inclusion.

More advanced data processing can occur with image processing, a technique developed in the late 1960s by NASA and the private sector to provide contrast enhancement, false color rendering and a variety of other techniques including use of two dimensional Fourier transforms. Since digital data is collected and stored in various ways, the two data sources may not be entirely compatible. So a GIS must be able to convert geographic data from one structure to another. In so doing, the implicit assumptions behind different ontologies and classifications require analysis.[34] Object ontologies have gained increasing prominence as a consequence of object-oriented programming and sustained work by Barry Smith and co-workers.

Spatial ETL

Spatial ETL tools provide the data processing functionality of traditional extract, transform, load (ETL) software, but with a primary focus on the ability to manage spatial data. They provide GIS users with the ability to translate data between different standards and proprietary formats, whilst geometrically transforming the data en route. These tools can come in the form of add-ins to existing wider-purpose software such as spreadsheets.

Spatial analysis

GIS spatial analysis is a rapidly changing field, and GIS packages are increasingly including analytical tools as standard built-in facilities, as optional toolsets, as add-ins or 'analysts'. In many instances these are provided by the original software suppliers (commercial vendors or collaborative non commercial development teams), while in other cases facilities have been developed and are provided by third parties. Furthermore, many products offer software development kits (SDKs), programming languages and language support, scripting facilities and/or special interfaces for developing one's own analytical tools or variants. The increased availability has created a new dimension to business intelligence termed "spatial intelligence" which, when openly delivered via intranet, democratizes access to geographic and social network data. Geospatial intelligence, based on GIS spatial analysis, has also become a key element for security. GIS as a whole can be described as conversion to a vectorial representation or to any other digitisation process.

Geoprocessing is a GIS operation used to manipulate spatial data. A typical geoprocessing operation takes an input dataset, performs an operation on that dataset, and returns the result of the operation as an output dataset. Common geoprocessing operations include geographic feature overlay, feature selection and analysis, topology processing, raster processing, and data conversion. Geoprocessing allows for definition, management, and analysis of information used to form decisions.[35]

Terrain analysis

Many geographic tasks involve the terrain, the shape of the surface of the earth, such as hydrology, earthworks, and biogeography. Thus, terrain data is often a core dataset in a GIS, usually in the form of a raster Digital elevation model (DEM) or a Triangulated irregular network (TIN). A variety of tools are available in most GIS software for analyzing terrain, often by creating derivative datasets that represent a specific aspect of the surface. Some of the most common include:

- Slope or grade is the steepness or gradient of a unit of terrain, usually measured as an angle in degrees or as a percentage.[36]

- Aspect can be defined as the direction in which a unit of terrain faces. Aspect is usually expressed in degrees from north.[37]

- Cut and fill is a computation of the difference between the surface before and after an excavation project to estimate costs.

- Hydrological modeling can provide a spatial element that other hydrological models lack, with the analysis of variables such as slope, aspect and watershed or catchment area.[38] Terrain analysis is fundamental to hydrology, since water always flows down a slope.[38] As basic terrain analysis of a digital elevation model (DEM) involves calculation of slope and aspect, DEMs are very useful for hydrological analysis. Slope and aspect can then be used to determine direction of surface runoff, and hence flow accumulation for the formation of streams, rivers and lakes. Areas of divergent flow can also give a clear indication of the boundaries of a catchment. Once a flow direction and accumulation matrix has been created, queries can be performed that show contributing or dispersal areas at a certain point.[38] More detail can be added to the model, such as terrain roughness, vegetation types and soil types, which can influence infiltration and evapotranspiration rates, and hence influencing surface flow. One of the main uses of hydrological modeling is in environmental contamination research. Other applications of hydrological modeling include groundwater and surface water mapping, as well as flood risk maps.

- Viewshed analysis predicts the impact that terrain has on the visibility between locations, which is especially important for wireless communications.

- Shaded relief is a depiction of the surface as if it were a three dimensional model lit from a given direction, which is very commonly used in maps.

Most of these are generated using algorithms that are discrete simplifications of vector calculus. Slope, aspect, and surface curvature in terrain analysis are all derived from neighborhood operations using elevation values of a cell's adjacent neighbours.[39] Each of these is strongly affected by the level of detail in the terrain data, such as the resolution of a DEM, which should be chosen carefully.[40]

Proximity analysis

Distance is a key part of solving many geographic tasks, usually due to the friction of distance. Thus, a wide variety of analysis tools have analyze distance in some form, such as buffers, Voronoi or Thiessen polygons, Cost distance analysis, and network analysis.

Data analysis

It is difficult to relate wetlands maps to rainfall amounts recorded at different points such as airports, television stations, and schools. A GIS, however, can be used to depict two- and three-dimensional characteristics of the Earth's surface, subsurface, and atmosphere from information points. For example, a GIS can quickly generate a map with isopleth or contour lines that indicate differing amounts of rainfall. Such a map can be thought of as a rainfall contour map. Many sophisticated methods can estimate the characteristics of surfaces from a limited number of point measurements. A two-dimensional contour map created from the surface modeling of rainfall point measurements may be overlaid and analyzed with any other map in a GIS covering the same area. This GIS derived map can then provide additional information - such as the viability of water power potential as a renewable energy source. Similarly, GIS can be used to compare other renewable energy resources to find the best geographic potential for a region.[41]

Additionally, from a series of three-dimensional points, or digital elevation model, isopleth lines representing elevation contours can be generated, along with slope analysis, shaded relief, and other elevation products. Watersheds can be easily defined for any given reach, by computing all of the areas contiguous and uphill from any given point of interest. Similarly, an expected thalweg of where surface water would want to travel in intermittent and permanent streams can be computed from elevation data in the GIS.

Topological modeling

A GIS can recognize and analyze the spatial relationships that exist within digitally stored spatial data. These topological relationships allow complex spatial modelling and analysis to be performed. Topological relationships between geometric entities traditionally include adjacency (what adjoins what), containment (what encloses what), and proximity (how close something is to something else).

Geometric networks

Geometric networks are linear networks of objects that can be used to represent interconnected features, and to perform special spatial analysis on them. A geometric network is composed of edges, which are connected at junction points, similar to graphs in mathematics and computer science. Just like graphs, networks can have weight and flow assigned to its edges, which can be used to represent various interconnected features more accurately. Geometric networks are often used to model road networks and public utility networks, such as electric, gas, and water networks. Network modeling is also commonly employed in transportation planning, hydrology modeling, and infrastructure modeling.

Cartographic modeling

Dana Tomlin coined the term "cartographic modeling" in his PhD dissertation (1983); he later used it in the title of his book, Geographic Information Systems and Cartographic Modeling (1990).[42] Cartographic modeling refers to a process where several thematic layers of the same area are produced, processed, and analyzed. Tomlin used raster layers, but the overlay method (see below) can be used more generally. Operations on map layers can be combined into algorithms, and eventually into simulation or optimization models.

Map overlay

The combination of several spatial datasets (points, lines, or polygons) creates a new output vector dataset, visually similar to stacking several maps of the same region. These overlays are similar to mathematical Venn diagram overlays. A union overlay combines the geographic features and attribute tables of both inputs into a single new output. An intersect overlay defines the area where both inputs overlap and retains a set of attribute fields for each. A symmetric difference overlay defines an output area that includes the total area of both inputs except for the overlapping area.

Data extraction is a GIS process similar to vector overlay, though it can be used in either vector or raster data analysis. Rather than combining the properties and features of both datasets, data extraction involves using a "clip" or "mask" to extract the features of one data set that fall within the spatial extent of another dataset.

In raster data analysis, the overlay of datasets is accomplished through a process known as "local operation on multiple rasters" or "map algebra", through a function that combines the values of each raster's matrix. This function may weigh some inputs more than others through use of an "index model" that reflects the influence of various factors upon a geographic phenomenon.

Geostatistics

Geostatistics is a branch of statistics that deals with field data, spatial data with a continuous index. It provides methods to model spatial correlation, and predict values at arbitrary locations (interpolation).

When phenomena are measured, the observation methods dictate the accuracy of any subsequent analysis. Due to the nature of the data (e.g. traffic patterns in an urban environment; weather patterns over the Pacific Ocean), a constant or dynamic degree of precision is always lost in the measurement. This loss of precision is determined from the scale and distribution of the data collection.

To determine the statistical relevance of the analysis, an average is determined so that points (gradients) outside of any immediate measurement can be included to determine their predicted behavior. This is due to the limitations of the applied statistic and data collection methods, and interpolation is required to predict the behavior of particles, points, and locations that are not directly measurable.

Interpolation is the process by which a surface is created, usually a raster dataset, through the input of data collected at a number of sample points. There are several forms of interpolation, each which treats the data differently, depending on the properties of the data set. In comparing interpolation methods, the first consideration should be whether or not the source data will change (exact or approximate). Next is whether the method is subjective, a human interpretation, or objective. Then there is the nature of transitions between points: are they abrupt or gradual. Finally, there is whether a method is global (it uses the entire data set to form the model), or local where an algorithm is repeated for a small section of terrain.

Interpolation is a justified measurement because of a spatial autocorrelation principle that recognizes that data collected at any position will have a great similarity to, or influence of those locations within its immediate vicinity.

Digital elevation models, triangulated irregular networks, edge-finding algorithms, Thiessen polygons, Fourier analysis, (weighted) moving averages, inverse distance weighting, kriging, spline, and trend surface analysis are all mathematical methods to produce interpolative data.

Address geocoding

Geocoding is interpolating spatial locations (X,Y coordinates) from street addresses or any other spatially referenced data such as ZIP Codes, parcel lots and address locations. A reference theme is required to geocode individual addresses, such as a road centerline file with address ranges. The individual address locations have historically been interpolated, or estimated, by examining address ranges along a road segment. These are usually provided in the form of a table or database. The software will then place a dot approximately where that address belongs along the segment of centerline. For example, an address point of 500 will be at the midpoint of a line segment that starts with address 1 and ends with address 1,000. Geocoding can also be applied against actual parcel data, typically from municipal tax maps. In this case, the result of the geocoding will be an actually positioned space as opposed to an interpolated point. This approach is being increasingly used to provide more precise location information.

Reverse geocoding

Reverse geocoding is the process of returning an estimated street address number as it relates to a given coordinate. For example, a user can click on a road centerline theme (thus providing a coordinate) and have information returned that reflects the estimated house number. This house number is interpolated from a range assigned to that road segment. If the user clicks at the midpoint of a segment that starts with address 1 and ends with 100, the returned value will be somewhere near 50. Note that reverse geocoding does not return actual addresses, only estimates of what should be there based on the predetermined range.

Multi-criteria decision analysis

Coupled with GIS, multi-criteria decision analysis methods support decision-makers in analysing a set of alternative spatial solutions, such as the most likely ecological habitat for restoration, against multiple criteria, such as vegetation cover or roads. MCDA uses decision rules to aggregate the criteria, which allows the alternative solutions to be ranked or prioritised.[43] GIS MCDA may reduce costs and time involved in identifying potential restoration sites.

GIS data mining

GIS or spatial data mining is the application of data mining methods to spatial data. Data mining, which is the partially automated search for hidden patterns in large databases, offers great potential benefits for applied GIS-based decision making. Typical applications include environmental monitoring. A characteristic of such applications is that spatial correlation between data measurements require the use of specialized algorithms for more efficient data analysis.[44]

Data output and cartography

Cartography is the design and production of maps, or visual representations of spatial data. The vast majority of modern cartography is done with the help of computers, usually using GIS but production of quality cartography is also achieved by importing layers into a design program to refine it. Most GIS software gives the user substantial control over the appearance of the data.

Cartographic work serves two major functions:

First, it produces graphics on the screen or on paper that convey the results of analysis to the people who make decisions about resources. Wall maps and other graphics can be generated, allowing the viewer to visualize and thereby understand the results of analyses or simulations of potential events. Web Map Servers facilitate distribution of generated maps through web browsers using various implementations of web-based application programming interfaces (AJAX, Java, Flash, etc.).

Second, other database information can be generated for further analysis or use. An example would be a list of all addresses within one mile (1.6 km) of a toxic spill.

An archeochrome is a new way of displaying spatial data. It is a thematic on a 3D map that is applied to a specific building or a part of a building. It is suited to the visual display of heat-loss data.

Terrain depiction

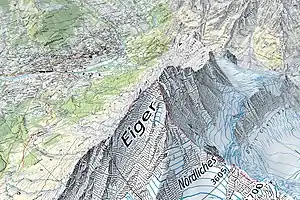

Traditional maps are abstractions of the real world, a sampling of important elements portrayed on a sheet of paper with symbols to represent physical objects. People who use maps must interpret these symbols. Topographic maps show the shape of land surface with contour lines or with shaded relief.

Today, graphic display techniques such as shading based on altitude in a GIS can make relationships among map elements visible, heightening one's ability to extract and analyze information. For example, two types of data were combined in a GIS to produce a perspective view of a portion of San Mateo County, California.

- The digital elevation model, consisting of surface elevations recorded on a 30-meter horizontal grid, shows high elevations as white and low elevation as black.

- The accompanying Landsat Thematic Mapper image shows a false-color infrared image looking down at the same area in 30-meter pixels, or picture elements, for the same coordinate points, pixel by pixel, as the elevation information.

A GIS was used to register and combine the two images to render the three-dimensional perspective view looking down the San Andreas Fault, using the Thematic Mapper image pixels, but shaded using the elevation of the landforms. The GIS display depends on the viewing point of the observer and time of day of the display, to properly render the shadows created by the sun's rays at that latitude, longitude, and time of day.

Web mapping

In recent years there has been a proliferation of free-to-use and easily accessible mapping software such as the proprietary web applications Google Maps and Bing Maps, as well as the free and open-source alternative OpenStreetMap. These services give the public access to huge amounts of geographic data, perceived by many users to be as trustworthy and usable as professional information.[45] For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, web maps hosted on dashboards were used to rapidly disseminate case data to the general public.[46]

Some of them, like Google Maps and OpenLayers, expose an application programming interface (API) that enable users to create custom applications. These toolkits commonly offer street maps, aerial/satellite imagery, geocoding, searches, and routing functionality. Web mapping has also uncovered the potential of crowdsourcing geodata in projects like OpenStreetMap, which is a collaborative project to create a free editable map of the world. These mashup projects have been proven to provide a high level of value and benefit to end users outside that possible through traditional geographic information.[47][48]

Web mapping is not without its drawbacks. Web mapping allows for the creation and distribution of maps by people without proper cartographic training.[49] This has led to maps that ignore cartographic conventions and are potentially misleading, with one study finding that more than half of United States state government COVID-19 dashboards did not follow these conventions.[50][51]

Applications

Since its origin in the 1960s, GIS has been used in an ever-increasing range of applications, corroborating the widespread importance of location and aided by the continuing reduction in the barriers to adopting geospatial technology. The perhaps hundreds of different uses of GIS can be classified in several ways:

- Goal: the purpose of an application can be broadly classified as either scientific research or resource management. The purpose of research, defined as broadly as possible, is to discover new knowledge; this may be performed by someone who considers herself a scientist, but may also be done by anyone who is trying to learn why the world appears to work the way it does. A study as practical as deciphering why a business location has failed would be research in this sense. Management (sometimes called operational applications), also defined as broadly as possible, is the application of knowledge to make practical decisions on how to employ the resources one has control over to achieve one's goals. These resources could be time, capital, labor, equipment, land, mineral deposits, wildlife, and so on.[52]: 791

- Decision level: Management applications have been further classified as strategic, tactical, operational, a common classification in business management.[53] Strategic tasks are long-term, visionary decisions about what goals one should have, such as whether a business should expand or not. Tactical tasks are medium-term decisions about how to achieve strategic goals, such as a national forest creating a grazing management plan. Operational decisions are concerned with the day-to-day tasks, such as a person finding the shortest route to a pizza restaurant.

- Topic: the domains in which GIS is applied largely fall into those concerned with the human world (e.g., economics, politics, transportation, education, landscape architecture, archaeology, urban planning, real estate, public health, crime mapping, national defense), and those concerned with the natural world (e.g., geology, biology, oceanography, climate). That said, one of the powerful capabilities of GIS and the spatial perspective of geography is their integrative ability to compare disparate topics, and many applications are concerned with multiple domains. Examples of integrated human-natural application domains include deep mapping,[54] Natural hazard mitigation, wildlife management, sustainable development,[55] natural resources, and climate change response.[56]

- Institution: GIS has been implemented in a variety of different kinds of institutions: government (at all levels from municipal to international), business (of all types and sizes), non-profit organizations (even churches), as well as personal uses. The latter has become increasingly prominent with the rise of location-enabled smartphones.

- Lifespan: GIS implementations may be focused on a project or an enterprise.[57] A Project GIS is focused on accomplishing a single task: data is gathered, analysis is performed, and results are produced separately from any other projects the person may perform, and the implementation is essentially transitory. An Enterprise GIS is intended to be a permanent institution, including a database that is carefully designed to be useful for a variety of projects over many years, and is likely used by many individuals across an enterprise, with some employed full-time just to maintain it.[58]

- Integration: Traditionally, most GIS applications were standalone, using specialized GIS software, specialized hardware, specialized data, and specialized professionals. Although these remain common to the present day, integrated applications have greatly increased, as geospatial technology was merged into broader enterprise applications, sharing IT infrastructure, databases, and software, often using enterprise integration platforms such as SAP.[59]

The implementation of a GIS is often driven by jurisdictional (such as a city), purpose, or application requirements. Generally, a GIS implementation may be custom-designed for an organization. Hence, a GIS deployment developed for an application, jurisdiction, enterprise, or purpose may not be necessarily interoperable or compatible with a GIS that has been developed for some other application, jurisdiction, enterprise, or purpose.[60]

GIS is also diverging into location-based services, which allows GPS-enabled mobile devices to display their location in relation to fixed objects (nearest restaurant, gas station, fire hydrant) or mobile objects (friends, children, police car), or to relay their position back to a central server for display or other processing.

Aquatic science

Archaeology

Environmental governance

Environmental contamination

Geologic mapping

Geospatial intelligence

History

Hydrology

Participatory GIS

Public health

Traditional knowledge GIS

Open Geospatial Consortium standards

The Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) is an international industry consortium of 384 companies, government agencies, universities, and individuals participating in a consensus process to develop publicly available geoprocessing specifications. Open interfaces and protocols defined by OpenGIS Specifications support interoperable solutions that "geo-enable" the Web, wireless and location-based services, and mainstream IT, and empower technology developers to make complex spatial information and services accessible and useful with all kinds of applications. Open Geospatial Consortium protocols include Web Map Service, and Web Feature Service.[71]

GIS products are broken down by the OGC into two categories, based on how completely and accurately the software follows the OGC specifications.

Compliant products are software products that comply to OGC's OpenGIS Specifications. When a product has been tested and certified as compliant through the OGC Testing Program, the product is automatically registered as "compliant" on this site.

Implementing products are software products that implement OpenGIS Specifications but have not yet passed a compliance test. Compliance tests are not available for all specifications. Developers can register their products as implementing draft or approved specifications, though OGC reserves the right to review and verify each entry.

Adding the dimension of time

The condition of the Earth's surface, atmosphere, and subsurface can be examined by feeding satellite data into a GIS. GIS technology gives researchers the ability to examine the variations in Earth processes over days, months, and years through the use of cartographic visualizations.[72] As an example, the changes in vegetation vigor through a growing season can be animated to determine when drought was most extensive in a particular region. The resulting graphic represents a rough measure of plant health. Working with two variables over time would then allow researchers to detect regional differences in the lag between a decline in rainfall and its effect on vegetation.

GIS technology and the availability of digital data on regional and global scales enable such analyses. The satellite sensor output used to generate a vegetation graphic is produced for example by the advanced very-high-resolution radiometer (AVHRR). This sensor system detects the amounts of energy reflected from the Earth's surface across various bands of the spectrum for surface areas of about 1 square kilometer. The satellite sensor produces images of a particular location on the Earth twice a day. AVHRR and more recently the moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) are only two of many sensor systems used for Earth surface analysis.

In addition to the integration of time in environmental studies, GIS is also being explored for its ability to track and model the progress of humans throughout their daily routines. A concrete example of progress in this area is the recent release of time-specific population data by the U.S. Census. In this data set, the populations of cities are shown for daytime and evening hours highlighting the pattern of concentration and dispersion generated by North American commuting patterns. The manipulation and generation of data required to produce this data would not have been possible without GIS.

Using models to project the data held by a GIS forward in time have enabled planners to test policy decisions using spatial decision support systems.

Semantics

Tools and technologies emerging from the World Wide Web Consortium's Semantic Web are proving useful for data integration problems in information systems. Correspondingly, such technologies have been proposed as a means to facilitate interoperability and data reuse among GIS applications and also to enable new analysis mechanisms.[73][74][75][76]

Ontologies are a key component of this semantic approach as they allow a formal, machine-readable specification of the concepts and relationships in a given domain. This in turn allows a GIS to focus on the intended meaning of data rather than its syntax or structure. For example, reasoning that a land cover type classified as deciduous needleleaf trees in one dataset is a specialization or subset of land cover type forest in another more roughly classified dataset can help a GIS automatically merge the two datasets under the more general land cover classification. Tentative ontologies have been developed in areas related to GIS applications, for example the hydrology ontology[77] developed by the Ordnance Survey in the United Kingdom and the SWEET ontologies[78] developed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Also, simpler ontologies and semantic metadata standards are being proposed by the W3C Geo Incubator Group[79] to represent geospatial data on the web. GeoSPARQL is a standard developed by the Ordnance Survey, United States Geological Survey, Natural Resources Canada, Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and others to support ontology creation and reasoning using well-understood OGC literals (GML, WKT), topological relationships (Simple Features, RCC8, DE-9IM), RDF and the SPARQL database query protocols.

Recent research results in this area can be seen in the International Conference on Geospatial Semantics[80] and the Terra Cognita – Directions to the Geospatial Semantic Web[81] workshop at the International Semantic Web Conference.

Societal implications

With the popularization of GIS in decision making, scholars have begun to scrutinize the social and political implications of GIS.[82][83][45] GIS can also be misused to distort reality for individual and political gain.[84][85] It has been argued that the production, distribution, utilization, and representation of geographic information are largely related with the social context and has the potential to increase citizen trust in government.[86] Other related topics include discussion on copyright, privacy, and censorship. A more optimistic social approach to GIS adoption is to use it as a tool for public participation.

In education

At the end of the 20th century, GIS began to be recognized as tools that could be used in the classroom.[87][88][89] The benefits of GIS in education seem focused on developing spatial cognition, but there is not enough bibliography or statistical data to show the concrete scope of the use of GIS in education around the world, although the expansion has been faster in those countries where the curriculum mentions them.[90]: 36

GIS seem to provide many advantages in teaching geography because they allow for analyses based on real geographic data and also help raise many research questions from teachers and students in classrooms. They also contribute to improvement in learning by developing spatial and geographical thinking and, in many cases, student motivation.[90]: 38

In local government

GIS is proven as an organization-wide, enterprise and enduring technology that continues to change how local government operates.[91] Government agencies have adopted GIS technology as a method to better manage the following areas of government organization:

- Economic development departments use interactive GIS mapping tools, aggregated with other data (demographics, labor force, business, industry, talent) along with a database of available commercial sites and buildings in order to attract investment and support existing business. Businesses making location decisions can use the tools to choose communities and sites that best match their criteria for success.

- Public safety[92] operations such as emergency operations centers, fire prevention, police and sheriff mobile technology and dispatch, and mapping weather risks.

- Parks and recreation departments and their functions in asset inventory, land conservation, land management, and cemetery management

- Public works and utilities, tracking water and stormwater drainage, electrical assets, engineering projects, and public transportation assets and trends

- Fiber network management for interdepartmental network assets

- School analytical and demographic data, asset management, and improvement/expansion planning

- Public administration for election data, property records, and zoning/management

The Open Data initiative is pushing local government to take advantage of technology such as GIS technology, as it encompasses the requirements to fit the Open Data/Open Government model of transparency.[91] With Open Data, local government organizations can implement Citizen Engagement applications and online portals, allowing citizens to see land information, report potholes and signage issues, view and sort parks by assets, view real-time crime rates and utility repairs, and much more.[93][94] The push for open data within government organizations is driving the growth in local government GIS technology spending, and database management.

See also

- AM/FM/GIS

- Climate Information Service

- Comparison of GIS software

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Distributed GIS

- Geomatics

- GISCorps

- GIS Day

- Integrated Geo Systems

- List of GIS data sources

- List of GIS software

- Map database management

- Quantitative geography

- Technical geography

- Tobler's first law of geography

- Tobler's second law of geography

- Virtual globe

References

- DeMers, Michael (2009). Fundamentals of Geographic Information Systems (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, inc. ISBN 978-0-470-12906-7.

- Chang, Kang-tsung (2016). Introduction to Geographic Information Systems (9th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-259-92964-9.

- Goodchild, Michael F (2010). "Twenty years of progress: GIScience in 2010". Journal of Spatial Information Science (1). doi:10.5311/JOSIS.2010.1.2.

- Maliene V, Grigonis V, Palevičius V, Griffiths S (2011). "Geographic information system: Old principles with new capabilities". Urban Design International. 16 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1057/udi.2010.25. S2CID 110827951.

- "The 50th Anniversary of GIS". ESRI. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- "Rapport sur la marche et les effets du choléra dans Paris et le département de la Seine. Année 1832". Gallica. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- MacHarg, Ian L. (1971). Design with nature. Natural History Press. OCLC 902596436.

- Broome, Frederick R.; Meixler, David B. (January 1990). "The TIGER Data Base Structure". Cartography and Geographic Information Systems. 17 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1559/152304090784005859. ISSN 1050-9844.

- Tobler, Waldo (1959). "Automation and Cartography". Geographical Review. 49 (4): 526–534. doi:10.2307/212211. JSTOR 212211. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- Fitzgerald, Joseph H. "Map Printing Methods". Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "History of GIS | Early History and the Future of GIS – Esri". www.esri.com. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- "Roger Tomlinson". UCGIS. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "GIS Hall of Fame – Roger Tomlinson". URISA. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- Lovison-Golob, Lucia. "Howard T. Fisher". Harvard University. Archived from the original on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2007.

- "Open Source GIS History – OSGeo Wiki Editors". Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- Xuan, Zhu (2016). GIS for Environmental Applications A practical approach. Routledge. ISBN 9780415829069. OCLC 1020670155.

- Fu, P., and J. Sun. 2010. Web GIS: Principles and Applications. ESRI Press. Redlands, CA. ISBN 1-58948-245-X.

- Bolstad, Paul (2019). GIS Fundamentals: A First Text on Geographic Information Systems (6th ed.). XanEdu. ISBN 978-1-59399-552-2.

- Ablimit Aji; Hoang Vo; Qiaoling Liu; Fusheng Wang; Joel Saltz; Rubao Lee; Xiaodong Zhang (2013). "Hadoop GIS: a high performance spatial data warehousing system over mapreduce". The 39th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment International Conference on Very Large Data Bases. Vol. 6, no. 11. pp. 1009–1020. PMC 3814183. PMID 24187650.

- Longley, Paul A.; Goodchilde, Michael F.; Maguire, David J.; Rhind, David W. (2015). Geographic Information Systems & Science (4th ed.). Wiley.

- Peng, Zhong-Ren; Tsou, Ming-Hsiang (2003). Internet GIS: Distributed Information Services for the Internet and Wireless Networks. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-35923-8. OCLC 50447645.

- Moretz, David (2008). "Internet GIS". In Shekhar, Shashi; Xiong, Hui (eds.). Encyclopedia of GIS. New York: Springer. pp. 591–596. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-35973-1_648. ISBN 978-0-387-35973-1. OCLC 233971247.

- Cowen, David (1988). "GIS versus CAD versus DBMS: What Are the Differences?" (PDF). Photogrammetric Engineering and Remote Sensing. 54 (11): 1551–1555. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- Marwick, Ben; Hiscock, Peter; Sullivan, Marjorie; Hughes, Philip (July 2017). "Landform boundary effects on Holocene forager landscape use in arid South Australia". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 19: 864–874. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.07.004. S2CID 134572456.

- Buławka, Nazarij; Chyla, Julia Maria (2020), "Mobile GIS in Archaeology – Current Possibilities, Future Needs Mobile GIS in Archaeology : Current Possibilities, Future Needs. Position Paper", CAA: Digital Archaeologies, Material Worlds (Past and Present), Tübingen: Tübingen University Press, ISBN 978-3-947-25115-5, S2CID 246410784

- "Aeryon Announces Version 5 of the Aeryon Scout System | Aeryon Labs Inc". Aeryon.com. 6 July 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Puotinen, Marji (June 2009). "A Primer of GIS: Fundamental Geographic and Cartographic Concepts - By Francis Harvey". Geographical Research. 47 (2): 219–221. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2009.00577.x. ISSN 1745-5863.

- "Digitizing - GIS Wiki | The GIS Encyclopedia". wiki.gis.com. Retrieved 2021-01-29.

- "Making maps compatible with GPS". Government of Ireland 1999. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- Jensen, John R.; Jensen, Ryan R. (2013). Introductory Geographic Information Systems. Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-614776-3.

- "Geospatial Positioning Accuracy Standards Part 3: National Standard for Spatial Data Accuracy". Archived from the original on 6 November 2018.

- "NJGIN's Information Warehouse". Njgin.state.nj.us. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Couclelis, Helen (March 2003). "The Certainty of Uncertainty: GIS and the Limits of Geographic Knowledge". Transactions in GIS. 7 (2): 165–175. doi:10.1111/1467-9671.00138. ISSN 1361-1682. S2CID 10269768.

- Winther, Rasmus G. (2014). C. Kendig (ed.). "Mapping Kinds in GIS and Cartography" (PDF). Natural Kinds and Classification in Scientific Practice. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-08.

- Wade, T. and Sommer, S. eds. A to Z GIS

- Jones, K.H. (1998). "A comparison of algorithms used to compute hill slope as a property of the DEM". Computers and Geosciences. 24 (4): 315–323. Bibcode:1998CG.....24..315J. doi:10.1016/S0098-3004(98)00032-6.

- Chang, K. T. (1989). "A comparison of techniques for calculating gradient and aspect from a gridded digital elevation model". International Journal of Geographical Information Science. 3 (4): 323–334. doi:10.1080/02693798908941519.

- Heywood I, Cornelius S, Carver S (2006). An Introduction to Geographical Information Systems (3rd ed.). Essex, England: Prentice Hall.

- Chang, K. T. (2008). Introduction to Geographical Information Systems. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 184.

- Longley, P. A.; Goodchild, M. F.; McGuire, D. J.; Rhind, D. W. (2005). "Analysis of errors of derived slope and aspect related to DEM data properties". Geographic Information Systems and Science. West Sussex, England: John Wiley and Sons: 328.

- K. Calvert, J. M. Pearce, W.E. Mabee, "Toward renewable energy geo-information infrastructures: Applications of GIScience and remote sensing that can build institutional capacity" Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 18, pp. 416–429 (2013). open access

- Tomlin, C. Dana (1990). Geographic information systems and cartographic modeling. Prentice Hall series in geographic information science. Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780133509274. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Greene, R.; Devillers, R.; Luther, J.E.; Eddy, B.G. (2011). "GIS-based multi-criteria analysis". Geography Compass. 5/6 (6): 412–432. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00431.x.

- Ma, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tian, X.; Ghanem, M. (2011). "Distributed Clustering-Based Aggregation Algorithm for Spatial Correlated Sensor Networks" (PDF). IEEE Sensors Journal. 11 (3): 641. Bibcode:2011ISenJ..11..641M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.724.1158. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2010.2056916. S2CID 1639100.

- Parker, Christopher J.; May, Andrew J.; Mitchell, Val (2013). "The role of VGI and PGI in supporting outdoor activities". Applied Ergonomics. 44 (6): 886–94. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2012.04.013. PMID 22795180. S2CID 12918341.

- Everts, Jonathan (2020). "The dashboard pandemic". Dialogues in Human Geography. 10 (2): 260–264. doi:10.1177/2043820620935355. S2CID 220418162.

- Parker, Christopher J.; May, Andrew J.; Mitchel, Val (2014). "User Centred Design of Neogeography: The Impact of Volunteered Geographic Information on Trust of Online Map 'Mashups" (PDF). Ergonomics. 57 (7): 987–997. doi:10.1080/00140139.2014.909950. PMID 24827070. S2CID 13458260. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-30.

- May, Andrew; Parker, Christopher J.; Taylor, Neil; Ross, Tracy (2014). "Evaluating a concept design of a crowd-sourced 'mashup' providing ease-of-access information for people with limited mobility". Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies. 49: 103–113. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2014.10.007.

- Plewe, Brandon (2007). "Web Cartography in the United States". Cartography and Geographic Information Science. 34 (2): 133–136. doi:10.1559/152304007781002235. S2CID 140717290.

- Adams, Aaron; Xiang, Chen; Weidong, Li; Zhang, Chuanrong (May 2020). "The disguised pandemic: The importance of data normalization in COVID-19 web mapping". Public Health. 183 (3): 36–37. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.034. PMC 7203028. PMID 32416476.

- Adams, Aaron M.; Chen, Xiang; Li, Weidong; Chuanrong, Zhang (27 July 2023). "Normalizing the pandemic: exploring the cartographic issues in state government COVID-19 dashboards". Journal of Maps. 19 (5): 1–9. doi:10.1080/17445647.2023.2235385.

- Longley, Paul; Goodchild, Michael F.; Maguire, David J.; Rhind, David W., eds. (1999). Geographical Information Systems, V.2: Management Issues and Applications (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0471-32182-6.

- Grimshaw, D.J. (1994). Bringing geographical information systems into business. Cambridge, UK: GeoInformation International.

- Butts, Shannon; Jones, Madison (2021-05-20). "Deep mapping for environmental communication design". Communication Design Quarterly. 9 (1): 4–19. doi:10.1145/3437000.3437001.

- "Off the Map | From Architectural Record and Greensource | Originally published in the March 2012 issues of Architectural Record and Greensource | McGraw-Hill Construction - Continuing Education Center". Continuingeducation.construction.com. 11 March 2011. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- "Arctic Sea Ice Extent is Third Lowest on Record".

- Huisman, Otto; de By, Rolf A. (2009). Principles of Geographic Information Systems: An introductory textbook (PDF). Enschede, The Netherlands: ITC. p. 44. ISBN 978-90-6164-269-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-05-14.

- Longley, Paul A.; Goodchild, Michael F.; Maguire, David J.; Rhind, David W. (2011). Geographic Information Systems & Science (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 434.

- Benner, Steve (Spring 2009). "Integrating GIS with SAP—The Imperative". Esri. Archived from the original on 22 October 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Kumar, Deepak; Das, Bhumika (23 May 2015). "Recent Trends in GIS Applications". SSRN 2609707.

- Conolly J and Lake M (2006) Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodchild, Michael F. (July 2009). "GIScience and Systems". pp. 526–538. doi:10.1016/B978-008044910-4.00029-8. ISBN 9780080449104.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - Demers, M. N. (2003). Fundamentals of Geographic Information Systems. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Longley, P. A., Goodchild, M. F., Maguire, D. J., & Rhind, D. W. (2005). Geographic Information Systems and Science. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Kocman, D., & Horvat, M. (2011). Non-point source mercury emission from the Idrija Hg-mine region: GIS mercury emission model. Journal of Environmental Management, 1–9.

- Jasminka, A., & Robert, S. (2011). Distribution of chemical elements in an old metallurgical area, Zenica. Geoderma, 71–85.

- Kramer, John (2000). "Digital Mapping Systems for Field Data Collection". Digital Mapping Techniques '00 -- Workshop Proceedings. U.S. Geological Survey. Open-File Report 00-325.

- Jo Abbot; Robert Chambers; Christine Dunn; Trevor Harris; Emmanuel de Merode; Gina Porter; Janet Townsend; Daniel Weiner (October 1998). "Participatory GIS: opportunity or oxymoron?" (PDF). PLA notes 33. pp. 27–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2010. Abbot, J. et al. 1998. [Participatory GIS: opportunity or oxymoron?] Participatory Learning & Action PLA Notes (IIED, Sustainable Agriculture & Rural Livelihoods), PLA 33, 27-34.

- Giacomo Rambaldi and Daniel Weiner (Track Leaders) (2004). "USA 3rd International Conference on Public Participation GIS (2004) - Track on International Perspectives: Summary Proceedings, University of Wisconsin–Madison, 18–20 July 2004, Madison, Wisconsin" (PDF). iapad.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- Peat, F. David. "I Have a Map in my Head." ReVision 18.3 (1996) : 11-17.

- "OGC Members | OGC(R)". Opengeospatial.org. Retrieved 13 May 2012.

- Monmonier, Mark (1990). "Strategies For The Visualization Of Geographic Time-Series Data". Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization. 27 (1): 30–45. doi:10.3138/U558-H737-6577-8U31.

- Zhang, Chuanrong; Zhao, Tian; Li, Weidong (2015). Geospatial Semantic Web. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-17801-1.

- Fonseca, Frederico; Sheth, Amit (2002). "The Geospatial Semantic Web" (PDF). UCGIS White Paper.

- Fonseca, Frederico; Egenhofer, Max (1999). "Ontology-Driven Geographic Information Systems". Proc. ACM International Symposium on Geographic Information Systems: 14–19. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.99.5206.

- Perry, Matthew; Hakimpour, Farshad; Sheth, Amit (2006). "Analyzing Theme, Space and Time: an Ontology-based Approach" (PDF). Proc. ACM International Symposium on Geographic Information Systems: 147–154.

- "Ordnance Survey Ontologies". Archived from the original on 21 May 2007.

- "Semantic Web for Earth and Environmental Terminology". Archived from the original on 29 May 2007.

- "W3C Geospatial Incubator Group".

- "International Conferences on Geospatial Semantics".

- "Terra Cognita 2006 – Directions to the Geospatial Semantic Web". Archived from the original on 18 May 2007.

- Haque, Akhlaque (1 May 2001). "GIS, Public Service, and the Issue of Democratic Governance". Public Administration Review. 61 (3): 259–265. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00028. ISSN 1540-6210.

- Haque, Akhlaque (2003). "Information technology, GIS and democraticvalues: Ethical implications for IT professionals in public service". Ethics and Information Technology. 5: 39–48. doi:10.1023/A:1024986003350. S2CID 44035634.

- Monmonier, Mark (2005). "Lying with Maps". Statistical Science. 20 (3): 215–222. doi:10.1214/088342305000000241. JSTOR 20061176.

- Monmonier, Mark (1991). How to Lie with Maps. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226534213.

- Haque, Akhlaque (2015). Surveillance, Transparency and Democracy: Public Administration in the Information Age. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0817318772.

- Sinton, Diana Stuart; Lund, Jennifer J., eds. (2007). Understanding place: GIS and mapping across the curriculum. Redlands, CA: ESRI Press. ISBN 9781589481497. OCLC 70866933.

- Milson, Andrew J.; Demirci, Ali; Kerski, Joseph J., eds. (2012). International perspectives on teaching and learning with GIS in secondary schools (Submitted manuscript). Dordrecht; New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2120-3. ISBN 9789400721197. OCLC 733249695.

- Solari, Osvaldo Muñiz; Demirci, Ali; Schee, Joop van der, eds. (2015). Geospatial technologies and geography education in a changing world: geospatial practices and lessons learned. Advances in Geographical and Environmental Sciences. Tōkyō; New York: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-55519-3. ISBN 9784431555186. OCLC 900306594. S2CID 130174652.

- Nieto Barbero, Gustavo (2016). Análisis de la práctica educativa con SIG en la enseñanza de la Geografía de la educación secundaria: un estudio de caso en Baden-Württemberg, Alemania (Ph.D. thesis). Barcelona: University of Barcelona. hdl:10803/400097.

- "Strategic GIS Planning and Management in Local Government". CRC Press. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- "Home - SafeCity". SafeCity. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- "GIS for Local Government| Open Government". www.esri.com. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Parker, C.J.; May, A.; Mitchell, V.; Burrows, A. (2013). "Capturing Volunteered Information for Inclusive Service Design: Potential Benefits and Challenges". The Design Journal (Submitted manuscript). 16 (2): 197–218. doi:10.2752/175630613x13584367984947. S2CID 110716823.

Further reading

- Berry, J. K. (1993). Beyond Mapping: Concepts, Algorithms and Issues in GIS. Fort Collins, CO: GIS World Books.