Thalweg

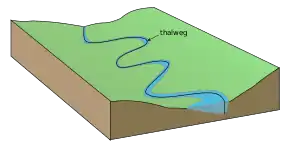

In geography, hydrography, and fluvial geomorphology, a thalweg or talweg (/ˈtɑːlvɛɡ/) is the line or curve of lowest elevation within a valley or watercourse.[1]

Under international law, a thalweg is taken to be the middle of the primary navigable channel of a waterway that defines the boundary line between entities such as states.[2][3] Thalwegs can acquire special significance because disputed river borders are often deemed to run along the river's thalweg.

Etymology

The word thalweg is of 19th-century German origin. The German word Thalweg (modern spelling Talweg) is a compound noun that is built from the German elements Thal (since Duden's orthography reform of 1901 written Tal) meaning valley (cognate with dale in English), and Weg, meaning way. It literally means "valley way" and is used, with its modern spelling Talweg, in daily German to describe a path or road that follows the bottom of a valley, or in geography with the more technical meaning also adopted by English.

Hydrology

In hydrological and fluvial landforms, the thalweg is a line drawn to join the lowest points along the entire length of a stream bed or valley in its downward slope, defining its deepest channel. The thalweg thus marks the natural direction (the profile) of a watercourse.

The term is also sometimes used to refer to a subterranean stream that percolates under the surface and in the same general direction as the surface stream.

Real world application

Slowing stream-bed erosion by taking advantage of a thalweg helps stabilize running water sources. Placing boulders along the thalweg in a running water source helps to protect the channel's sedimentary erosion and deposit balance. In concurrence with the placement of boulders along a thalweg, the placement of boulders along an instream to form artificial sills also helps to slow the sedimentary erosion and deposit of running water sources, while keeping the esteem (fishing, local wildlife, and recreation) and natural resources[4] of the running water source intact. The placement of boulders along a thalweg and the creation of instream sills help to aid the flow of water during late summer months when the flow rate drops, and help to slow sedimentary erosion and deposit in the spring and fall months when the flow rates are high. This process of utilizing a thalweg to slow stream-bed erosion was used in Meacham Creek in Umatilla, Oregon.[5]

Thalweg principle

.PNG.webp)

The thalweg principle (also known as the thalweg doctrine or the rule of thalweg) is the legal principle that if the boundary between two political entities is stated to be a waterway, without further description (e.g., a median line, right bank, eastern shore, low tide line, etc.), the boundary follows the thalweg of that watercourse. In particular, the boundary follows the center of the principal navigable channel of the waterway (which is presumably the deepest part). If there are multiple navigable channels in a river, the one principally used for downstream travel (likely having the strongest current) is used.[6] This definition has been used in specific descriptions as well. The Treaty of Versailles, for example, specifies that "In the case of boundaries which are defined by a [navigable] waterway" the boundary is to follow "the median line of the principal channel of navigation."[7]

The precise drawing of river boundaries has been important on countless occasions. Notable examples include the Shatt al-Arab between Iraq and Iran, the Danube in central Europe (Croatia–Serbia border dispute), the Kasikili/Sedudu Island dispute between Namibia and Botswana (settled by the International Court of Justice in 1999),[8] and the 2004 dispute settlement under the UN Law of the Sea concerning the offshore boundary between Guyana and Suriname, in which the thalweg of the Courantyne River played a role in the ruling.[9][10] In the 20th century dispute between the USSR and China (PRC) over Zhenbao Island, China held that the Thalweg principle supported their position.[11] The doctrine is also applied to sub-national boundaries, such as those between American states.[12]

In rivers with occasional flooding and especially ice cover which breaks in the spring, the thalweg can change. This can mean that the border might move if it is defined as the thalweg. The Finland–Sweden border has been moved several times due to this.

Mathematics

In the field of topology, the thalweg can be described as a parametrised curve. If the elevation of the valley floor at some position with coordinates (x, y) is represented by a surface z(x, y), then the negative gradient vector field -∇z(x, y) equips each position (x, y) with a vector pointing downhill in the direction of steepest slope (or by analogy, the direction a ball would roll if released from this position in the valley). Any parametrised curve that is everywhere directed along the gradient vector field eventually joins the thalweg (or using the same analogy, you can release a ball from any position in the valley, and it will eventually meet and then roll along the thalweg, assuming a smooth rolling surface so the ball doesn't get stuck, and also assuming sufficient rolling resistance or wind resistance that the ball doesn't roll down one side of the valley, up the other side and then oscillate back and forth). So, in this sense, the thalweg can be defined as the parametrised curve to which the gradient field converges.

See also

- Stream gradient – Surface slope along a watercourse

References

- "Webster Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2018-06-24. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- "dictionary.com". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- "Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- "Instream Flows". Washington State Department of Ecology. 18 January 2013. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Umatilla River Basin Anadromous Fish Habitat Enhancement Project 1990 Annual Report Carl A. Sheeler, Fish Habitat Biologist Slatick, January 1991

- A. Oye Cukwurah, The Settlement of Boundary Disputes in International Law, Manchester University Press, 1967, pp. 51 ff.

- Treaty of Versailles, Article 30.

- "Kasikili/Sedudu Island (Botswana/Namibia)". International Court of Justice. 13 December 1999. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- Permanent Court of Arbitration - Guyana/Suriname Archived 2013-02-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Award of the Tribunal Archived 2011-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Gurton, Melvin; Byong-Moo Hwang (1980). China under Threat: The Politics of Strategy and Diplomacy. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-8018-2397-8. LCCN 80-7990. OCLC 470966163.

- E.g., New Jersey v. Delaware, 291 U.S. 361, 78 L.Ed. 847, 54 S.Ct. 407 (1934).