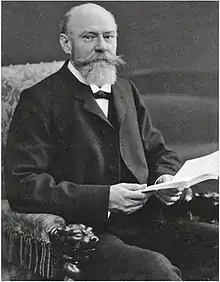

Georg Ledderhose

Georg Otto Ledderhose (15 December 1855 – 1 February 1925) was a German surgeon, professor and pioneering traumatologist.

Georg Ledderhose | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 15, 1855 |

| Died | February 1, 1925 (aged 69) |

| Education | University of Strasbourg, University of Göttingen |

| Occupation(s) | Surgeon, professor |

| Years active | 1880-1920 |

| Known for | Ledderhose's disease |

| Medical career | |

| Field | Surgery, Traumatology, Orthopedics |

| Institutions | University of Strasbourg, Hôpital Civil, University of Munich |

Biography

Early life

He was born in the Bockenheim district of Frankfurt am Main. His father was the politician and university rector Karl Ledderhose (26 March 1821 - 1 January 1899) and his mother was Wilhelmine Justine Charlotte (nee Pfeiffer; 21 October 1826 - 29 June 1892). Wilhelmine's father was Johann Georg Heinrich Pfeiffer (14 December 1781 - 27 January 1859), the third son of Johann Jakob Pfeiffer, and brother of Burkhard Wilhelm, Carl Jonas, and Franz Georg Pfeiffer.[1] Two of Ledderhose's uncles, the husbands of his mother's sisters, were the chemist Friedrich Wöhler and the jurist Otto Bähr, and another of his mother's sisters was the mother of the Prussian cavalry general Adolf von Deines.[1] At the time of Georg's birth, his father Carl was serving as a magistrate in the Hessian municipal court, and by 1865, when Georg was only ten years old, Karl had risen to the rank of Electoral Finance minister.[2] By 1871, Karl had been appointed vice president of the Prussian province of Alsace-Lorraine, as well as rector of the University of Strasbourg, and he would hold the latter position until 1887.[3]

Education

Ledderhose studied medicine at the University of Strasbourg under Georg Albert Lücke, as well as the University of Göttingen under his uncle Friedrich Wöhler. In 1876, while at Göttingen, Ledderhose was enjoying a dinner of lobster with his uncle Freidrich and his professor Felix Hoppe-Seyler, when his uncle suggested that he take the remains of the lobster back to the laboratory.[4] Intrigued, Ledderhose did so, and after exposing the chitinous shells to several compounds, he realized that a concentrated solution of hydrochloric acid caused the shells to dissolve and leave a residue of crystals.[5] Ledderhose later examined these crystals, and determining them to be a discovery new to science, christened them glycosamine.[6][7] (Although first identified by Ledderhose, the stereochemistry of the compound was not fully defined until 1939 by the work of Walter Haworth.[8][9])

Career and later life

Ledderhose received his medical degree from the University of Strasbourg in 1880, after which he practiced surgery at the Hôpital Civil. In 1886, Ledderhose was sent from Strasbourg to Paris, along with other eminent European doctors, including Karl Theodor, Duke in Bavaria, to study the novel techniques of Dr. Louis Pasteur.[10] In 1890, Ledderhose married Marie Caroline Pauline Emma Scharrer (30 June 1868 – 21 January 1950), great-granddaughter of the merchant, banker, and sometime burgermeister of Nuremberg Johannes Scharrer. Emma's brother was the celebrated dramaturg and biographer Eduard Scharrer-Santen (1869-1942).[11] They had two children:

- Elisabeth (5 July 1893 – 27 May 1985)

- Georg (3 September 1895 – 26 February 1994), who followed his father into medicine. The younger Georg and his wife Maria Freundlieb were the parents of the German art historian Lothar Ledderose.

From 1891, he was named a professor in surgery at his alma mater by his mentor Dr. Lücke.[12] Among his students in the practice of surgery was the polymath and Nobel laureate Albert Schweitzer.[13] In 1892, Ledderhose was commissioned by the city of Strasbourg to create a Rekonvaleszentenhaus or convalescent center, for those involved in traumatic accidents.[14] Due to the success of this institution, Ledderhose was later commissioned to supervise the planning and construction of a second traumatology center in Strasbourg, the Unfallkrankenhaus, which opened to the public on 27 November 1901.[14] He remained the director of the Unfallkrankenhaus through the years of the First World War until November 1918, when the victorious French government expelled the majority of Germans living in the territory of Alsace-Lorraine. According to the Alsatian journalist and memoirist Charles Spindler, Ledderhose was known in Strasbourg during the war as a man who provided care and support to the wounded on both sides of the conflict, and who made sure that charitable funds were distributed not only to the Germans, but also the French, and so the French government's summary exile of the doctor came as quite a shock to the populace.[15] Forced to flee the city that had been his home for his entire adult life, Ledderhose resettled in Munich, where the faculty at the University of Munich made him an honorary professor, and where he taught until his retirement and death.[16]

Legacy

In addition to his work in discovering glucosamine, Ledderhose is perhaps most famous today for being the first to describe the condition of plantar fibromatosis in 1894, which is now known as Ledderhose's disease in his honor.[17][18]

Publications

- Über Glykosamin. Trübner, Straßburg 1880 (Dissertation).

- Beiträge zur Kenntniss des Verhaltens von Blutergüssen in serösen Höhlen unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der peritonealen Bluttransfusion. Trübner, Straßburg 1885.

- Die chirurgischen Erkrankungen der Bauchdecken und die chirurgischen Krankheiten der Milz (= Deutsche Chirurgie. Bd. 45b). Enke, Stuttgart 1890.

- Die ärztliche Untersuchung und Beurtheilung der Unfallfolgen. Bergmann, Wiesbaden 1898.

- Die Arthritis deformans als Allgemeinerkrankungen. Trübner, Straßburg 1915.

- Chirurgie des Thorax und der Brustdrüse (= Diagnostische und therapeutische Irrtümer und deren Verhütung: Chirurgie. Bd. 1). Thieme, Leipzig 1920.

- Chirurgie der Wirbelsäule, des Rückenmarks, der Bauchdecken und des Beckens (= Diagnostische und therapeutische Irrtümer und deren Verhütung: Chirurgie. Bd. 2). Thieme, Leipzig 1921.

- Spätfolgen der Unfallverletzungen: Ihre Untersuchung und Begutachtung. Enke, Stuttgart 1921.

References

- Pfeiffer, August Ludwig (1886). Die Familie Pfeiffer: Eine Sammlung von Lebensbildern und Stammbäumen. Kassel: Druck von Friedr. Scheel.

- Brandes, Gustav (1934). Die Familien "du Pré" oder "Dupré" - "von der Wiese". Dresden.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Frederic B. M. Hollyday (7 February 2017). Bismarck's Rival: A Political Biography of General and Admiral Albrecht von Stosch. Normanby Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-78720-383-9.

- Loudon, G. Marc (2009). Organic Chemistry. Greenwood Village: Roberts and Company.

- Horton, Derek (1965). "Monosaccharide Amino Sugars". In Balazs, Endre; Jeanloz, Roger (eds.). The Amino Sugars: The Chemistry and Biology of Compounds Containing Amino Sugars. Vol. 1A: The Chemistry of Amino Sugars. New York: Academic Press.

- Georg Ledderhose (1876) "Über salzsaures Glycosamin" [On glucosamine hydrochloride], Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 9(2): 1200-1201.

- Joseph S. Fruton (1990). Contrasts in Scientific Style: Research Groups in the Chemical and Biochemical Sciences. DIANE. p. 313. ISBN 0-87169-191-4.

- W. N. Haworth, W. H. G. Lake, and S. Peat (1939) "The configuration of glucosamine (chitosamine)," Journal of the Chemical Society, pages 271-274.

- Horton, Derek; Wander, J.D. (1980). The Carbohydrates Vol IB. New York: Academic Press. pp. 727–728. ISBN 0-12-556351-5.

- “Paris.” The British Medical Journal 1, no. 1319 (1886): 714–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25275599.

- Degener, Hermann, ed. (1922). Wer Ist's? (VIII ed.). Leipzig: Ludwig Degener. pp. 1334–1335.

- Anger, V (1990). Le docteur Edgar Stulz (1893-1963). Esquisse d'une biographie (MD). Strasbourg.

- Schweitzer, Albert (1931). Aus Meinem Leben und Denken. Leipzig: Felix Meiner Verlag. p. 64. translated as Schweitzer, Albert (1998). Out of My Life and Thought: An Autobiography. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6097-3.

- Muller-Pinelli, Jeannine (1974). Histoire du Centre de traumatologie de Strasbourg (MD). Strasbourg.

- Spindler, Charles (1925). "11 octobre 1914". L'Alsace pendant la guerre. 1914-1918. Strasbourg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Tagesgeschichte". Zeitschrift für ärztliche Fortbildung. Ernst von Bergmann. 16 (18): 544. 15 September 1919.

- Ledderhose G (1894). "Ueber Zerreisungen der Plantarfascie (On tears in the plantar fascia)". Archiv für Klinische Chirurgie. 48: 853–856.

- "Dupuytren's contracture - Patient UK". Retrieved 2007-12-28.