George Washington's political evolution

George Washington's political evolution comprised the transformation of a young man from a moderately wealthy family in the British colony of Virginia motivated largely by self-interest into the first president of the United States and one of the Founding Fathers. Washington was ambitious for the status and influence with which he had been surrounded in a youth spent around his half-brother Lawrence and the influential Fairfax family Lawrence married into. After working as a surveyor, a position he gained with the patronage of the Fairfaxes, Washington sought to emulate his brother's military career with a commission in the Virginia militia, despite his lack of military experience. With the patronage of more influential people, he was appointed major in 1752. The following year, he was appointed special envoy charged with delivering to the French a demand to vacate territory claimed by the British. His successful completion of this task gained him his first measure of renown. Washington was promoted in 1754 and made second-in-command of the Virginia Regiment. He enhanced his reputation with his first military victory in the Battle of Jumonville Glen, a skirmish that ignited the French and Indian War. He was promoted again in 1755 and given command of the regiment, serving until his resignation in 1758. During his military service, Washington grew disillusioned with the British because of his treatment as a second-class citizen and the defensive strategy they adopted during the war. He gained no further opportunity for military honor and failed to achieve his ambition of a royal commission in the British Army.

George Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| Major, Virginia Militia | |

| In office November 1752 – February 1754 | |

| Colonel, Virginia Regiment | |

| In office February 1754 – December 1758 | |

| Member, Virginia House of Burgesses | |

| In office July 1758 – June 1775 | |

| Delegate, First Continental Congress | |

| In office September 1774 – October 1774 | |

| Delegate, Second Continental Congress | |

| In office May 1775 – June 1775 | |

| Commander-in-Chief, Continental Army | |

| In office June 1775 – December 1783 | |

| President, Constitutional Convention | |

| In office May 1787 – September 1787 | |

| President of the United States | |

| In office April 1789 – March 1797 | |

His election to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1758 and his marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis the next year gave Washington wealth, real estate and social advancement to the upper echelons of Virginia society. He focused more on his business interests at his Mount Vernon plantation than his political career as a burgess and was an aggressive speculator in real estate. Washington became increasingly disillusioned by colonial dependence on Great Britain, the obstacles British policy placed in the way of his business interests, and the overbearing authority exercised by the British in colonial affairs. By 1769, he was denouncing British policy as a threat to liberty and was one of the first to speak of a resort to arms. He became increasingly involved in politics and was elected as one of the Virginia delegates to the First and Second Continental Congresses. His election to command the Continental Army in 1775 at the start of the American Revolutionary War completed Washington's transformation from someone intent on self-advancement to someone who advanced the cause of an independent republic. Victory cemented Washington's reputation, and his relinquishing of the command of the army in 1783 won him widespread acclaim as a modern-day Cincinnatus. After the war, Washington played a key role in establishing a strong national government and served two terms as the first president of the United States.

Washington was eulogized after his death in 1799 as a patriot devoid of ambition. Modern historians conclude that ambition was a driving force in his career and frequently characterize it as a desire for fame and honor. Once Washington gained a reputation he became very protective of it. His decisions to accept public office were often informed by the effect they would have on his reputation. Cultivating an image of a disinterested patriot, he ceased soliciting important appointments as he had done in his early career. Instead, he hesitated to accept public office, frequently protesting his inadequacy and insisting that he was accepting only at the entreaty of his friends or the call of his country. Historians are divided on Washington's true motivations; some maintain that public office was a burden he was genuinely reluctant to take on, others that reluctance was a political technique he employed to increase his authority and influence.

Young Washington

George Washington was born in the British Colony of Virginia on February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731], the eldest child of Augustine and Mary Ball Washington, Augustine's second wife. His father was a moderately wealthy tobacco planter and land speculator who achieved some prominence in northern Virginia as a local official. At birth, Washington had three half-siblings, the oldest being Lawrence.[1][2] When their father died in 1743, George inherited the 260-acre (1.1 km2) Ferry Farm and Lawrence inherited the 2,500-acre (10 km2) Little Hunting Creek estate on the Potomac, which he renamed Mount Vernon.[3] Lawrence had been an officer in the British Army, leading colonial troops alongside the British in the War of Jenkins' Ear. On his return, he was appointed adjutant general of the Virginia militia and surpassed his father's civic career with his election to the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg.[lower-alpha 1] Lawrence cemented his place in the top echelon of Virginia society when he married Ann Fairfax, eldest daughter of William Fairfax, a leading Virginia figure who presided over some six million acres (twenty-four thousand square kilometers) of land.[5][6]

Lawrence became a father figure and role model for George, while George's hypercritical mother made him taciturn and sensitive to criticism, instilling in him a lifelong need for approval.[6][7] George's visits to his brother at Mount Vernon and his brother's in-laws at their Belvoir plantation introduced him to the cultivated manners and opulence of Virginia high society. What he saw inspired in him an ambition for the same status and place in the influential world of planter aristocracy.[8] As he approached adulthood, Washington learned to ingratiate himself with older, influential figures whose patronage would help him ascend the social ladder.[9] He spent a year studying surveying, and after gaining hands-on experience accompanying a Fairfax surveying team, the seventeen-year-old Washington was appointed surveyor of Culpeper County.[10] The job was Washington's introduction to politics; it carried a similar status to a doctor, attorney or clergyman, and the patronage of Fairfax facilitated Washington's appointment without requiring him to first serve the usual period as an apprentice or deputy. As well as providing Washington with an income, the job provided an opportunity to speculate in land. By May 1753, he had acquired some 2,500 acres on the Virginia frontier.[11][12]

Major Washington

When Lawrence lay dying of tuberculosis in early 1752, the Virginia militia was divided into four military districts, each commanded by an adjutant with the colonial rank of major. Despite his lack of military experience, Washington lobbied Governor Robert Dinwiddie for an adjutancy. With the political influence of his patrons, Washington was appointed to the Southern District in November 1752. Unhappy with a post so far from his residence, he then successfully lobbied the Executive Council for a transfer to his home Northern Neck district in early 1753.[13][14][15]

The same year, Washington volunteered his services as a special envoy, an appointment he secured with the support of Fairfax. He was tasked to deliver a demand to the French that they vacate territory in the Ohio Country claimed by the British. He completed his mission in 77 days, returning not only with the French response asserting their claim to the territory but also with valuable intelligence as to their strength. He gained some recognition when his report was published in the colonies and Great Britain.[16][17]

Colonel Washington

When the 300-strong Virginia Regiment was formed in February 1754, Washington again enlisted the support of influential figures to secure promotion to lieutenant colonel and the job of the regiment's second-in-command. He declared his sole motive was "sincere love for my country" and professed that command of the whole force was "a charge too great for my youth and inexperience."[18][19]

Securing a reputation

On April 2, Washington set off with an advance guard of some half of the regiment for the Forks of the Ohio.[20][21] He defied orders to remain on the defensive by ambushing a French force of fewer than 50 men in the Battle of Jumonville Glen on May 28, 1754. The skirmish was a one-sided victory for Washington and the spark that ignited the French and Indian War.[22][23] Within days, Washington succeeded to the command of the regiment and was promoted colonel following the death of the regiment's commander, Colonel Joshua Fry.[24] On July 3, the French forced Washington to surrender in the Battle of Fort Necessity. Washington's camp was poorly situated and his force was outnumbered even after having been reinforced by the rest of the Virginia Regiment and an independent company of South Carolinians led by Captain James Mackay.[25]

Accounts of Washington's victory at Jumonville Glen were published in the colonies and Great Britain. He gained public honor and widespread acknowledgment for the victory, but the defeat at Fort Necessity damaged his reputation.[26][27][lower-alpha 2] In Great Britain, Lord Albemarle saw the defeat as proof of the inadequacy of colonial troops and the necessity for them to be led by regular officers of the British Army.[33] Washington's ambition to emulate his late brother's military status ended in disappointment when the Virginia Regiment was broken up into independent companies, each commanded by a captain. Citing the "call of Honour [sic]", he resigned his commission rather than accept demotion. Military service still remained the best path to advancement for a young man who had not inherited vast wealth, and Washington affirmed after his resignation that his "inclinations are strongly bent to arms."[34][35]

In pursuit of a royal commission

Governor Horatio Sharpe of Maryland accused Washington of acting recklessly at Fort Necessity out of pique arising from a dispute with Mackay over seniority.[33] Despite his nominally inferior rank, Mackay held a royal commission in the regular army which meant that, under British law, he outranked provincial officers. Neither Mackay nor Washington would accept subordination to the other.[36][37] Washington complained repeatedly to Dinwiddie about the inequalities of rank and pay between provincials and regulars. More than once he threatened to resign his commission. He was mollified by Dinwiddie's assurance that his continued good conduct would be rewarded with a royal commission.[38]

When Major General Edward Braddock arrived with two regiments of the British Army in February 1755 to eject the French from Fort Duquesne, Washington "rushed off a politic greeting to the general"[39] and, thanks to friends who solicited favor on his behalf, was offered a place on Braddock's staff. Still unwilling to accept demotion, Washington refused the rank of brevet captain and served voluntarily as an aide. He professed a desire to serve king and country "with my poor abilitys" and to seek the "regard & esteem" of his friends and province, and hoped the opportunity would provide him with military experience and connections that would further his military ambitions.[40][41] Although Braddock's promise to support Washington's promotion died with the general in the British defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela in July, Washington's exceptional courage during the battle boosted his reputation considerably. He received the esteem he sought from Dinwiddie, Fairfax and the Virginia ruling class and was widely acclaimed throughout the colonies and in Great Britain.[42][43]

When the Virginia Regiment was reconstituted in August 1755, Washington's friends pressed Dinwiddie to appoint him commander and urged him to present his case in person. He declined to do so, saying that he preferred the appointment to be "press'd upon me by the general voice of the country and offered upon such terms as can’t be objected against."[44][45] His hesitation allowed him to insist on those terms, and on August 31, two weeks after being offered the position, he accepted the rank of colonel and command of all provincial forces in Virginia.[46] Almost immediately, Washington clashed again over rank, this time with John Dagworthy. Although only a captain in the colonial militia, Dagworthy claimed seniority based on a royal commission he had received in 1746.[47]

Disillusionment

Amid rumors the Virginia Regiment would be incorporated into the regular establishment, Washington oversaw the training and discipline that would bring the regiment up to professional standards. He became frustrated with the defensive strategy adopted by the British and agitated for an offensive against Fort Duquesne. When William Shirley, Braddock's successor as commander of British forces in North America, did not reply to Dinwiddie's letter supporting Washington's promotion to the regular army, Washington traveled to Boston in February 1756 to make his case. Shirley ruled in Washington's favor in the matter of Dagworthy, but little else. There would be no royal commission for Washington, no place in the regular establishment for his regiment, and no opportunity for further honor leading an assault on Fort Duquesne.[48][49][50]

In January 1757, Washington raised these issues with Shirley's successor, Lord Loudoun. When the two met in Philadelphia later that year, Loudoun – who had a low opinion of colonial troops – treated Washington with disdain and gave him no opportunity to make his case.[51][52] Washington's relationships with British officials were further strained when his strident advocacy for a more aggressive strategy in the war, to the point of going behind Dinwiddie's back and complaining to the House of Burgesses, alienated Dinwiddie.[53][54] By March 1758, Washington regarded his chances of securing a royal commission to be slim and was considering resignation from the Virginia Regiment.[55]

The news that month that Brigadier General John Forbes would lead another expedition to take Fort Duquesne convinced Washington to remain with the regiment. He sought to curry favor with Forbes, presenting himself as "a person who would gladly be distinguished in some measure from the common run of provincial officers", but made it clear that he no longer expected a royal commission.[56] Although the two had clashed over the choice of route,[lower-alpha 3] in November Forbes gave Washington the rank of brevet brigadier general and command of one of the three temporary brigades tasked with assaulting the fort, but the French withdrew before the assault could be launched. With the immediate threat to Virginia eliminated, Washington's quest for further military laurels and a royal commission came to nothing; he barely figured in British and colonial accounts of the expedition. Suffering from poor health, Washington resigned his commission in December.[58][59]

Among the laudatory farewells of his officers, Washington was hailed as "the darling of a grateful country" (that is, Virginia), a regard in which he gloried. In his response, he hinted at the "uncommon difficulties" he had faced, a reference to the problems he encountered with British officials such as Dinwiddie, Loudoun and Forbes.[60][61] Washington regarded the unequal treatment of himself and colonial forces as evidence of anti-colonial discrimination. He began to connect that grievance with a wider grievance against British authority.[62][63] The man who began his military career as a patriotic, loyal British subject eager to defend king and country was beginning to question colonial subordination within the British Empire.[64] The failure of other colonies to assist Virginia and intercolonial rivalry during the war fostered in Washington a belief in the need for continental unity and a predisposition for strong central government.[65]

Mr. Washington Esq.

Washington returned home to devote time to his imminent marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis, his plantation at Mount Vernon[lower-alpha 4] and his political career in the House of Burgesses.[67][68] Martha's dowry provided Washington with wealth, real estate and the social advancement to the upper echelons of Virginia society he had been seeking in his military service.[69] In 1766, after tobacco cultivation had proved unprofitable, he turned to wheat as his main cash crop.[70] Around the same time, he sought greater economic independence for himself with the manufacture of cloth and ironware rather than purchasing them from Great Britain.[71]

In 1757, Washington had added 500 acres (2 km2) to Mount Vernon by the purchase of neighboring properties, the beginning of an expansion that would ultimately result in an 8,000-acre (32 km2) estate. The following year he had started the work of expanding the residence that would eventually transform his brother's farmhouse into a mansion.[72] Washington spent lavishly on his residence, furnishing it with luxuries imported from Great Britain.[73] By 1764, his profligate spending had put him £1,800 in debt to his London agent, but his taste for luxury goods remained undiminished.[74] He grew increasingly resentful in his correspondence with his agent, accusing him of providing substandard goods at inflated prices and being too quick to demand payment. But Washington was dependent on Great Britain for manufactured goods. It was a dependency that undermined economic self-determination in the colonies and led to significant levels of debt among rich Virginia planters, both causes for further disillusionment with Great Britain.[71][75]

Land speculation

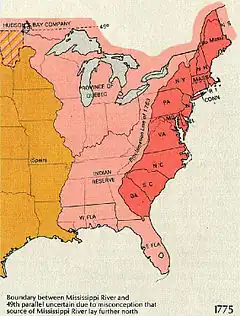

Washington was an aggressive speculator in real estate.[76] He was part of a syndicate, formed in 1763 to drain the Great Dismal Swamp and convert it to farmland, which circumvented restrictions on the amount of land that could be granted by submitting petitions for land under bogus names. The same year, he joined 19 other investors in the Mississippi Land Company, formed to claim 2.5 million acres (10,000 km2) of land in the Ohio valley.[77][78] The Royal Proclamation of 1763 banning settlement west of the Allegheny Mountains threatened Washington's land speculation activities, but the land was re-opened to settlers after the British concluded treaties with the Cherokee tribe and the Iroquois Confederacy in 1768.[79]

In the late 1760s and early 1770s, Washington pursued on his own behalf and the behalf of his former comrades in the Virginia Regiment land bounty claims promised in 1754 to veterans of the Fort Necessity campaign. By his efforts, which were not entirely without self-interest,[lower-alpha 5] Washington more than doubled the land in his possession. He increased his holdings further by purchasing the allocations of other veterans at mostly give-away prices, leading to feelings among some veterans of being duped. He stood to gain more by the grant of land to officers who had been serving at the end of the French and Indian War. Having resigned before the war's end, Washington was ineligible, but he persuaded Lord Dunmore, who had become governor of Virginia in 1771, to grant him a colonel's entitlement of 5,000 acres (20 km2), which he doubled by the purchase of another officer's entitlement. He occasionally disguised his interest by having family members buy veterans' claims for him under their names. By 1774, Washington had amassed some 32,000 acres (130 km2) of land.[83][84][85]

As the west was opened up to settlement, Washington began to actively promote plans for a canal to improve the navigability of the Potomac. Improved transportation would not only boost the value of his own landholdings in the west but lead to economic self-determination for the colonies. It would allow foodstuffs produced by Ohio Country farmers to be exported abroad, making it the channel for, in Washington's words, "the extensive and valuable Trade of a rising Empire" in which Virginia would, he hoped, play a leading role.[86]

Burgess Washington

In 1758, while serving with the Virginia Regiment, Washington sought election to the House of Burgesses. Although he secured leave to campaign, he remained with his troops and relied on friends to campaign for him. Washington topped the poll.[87] He was reelected in 1765 and returned without opposition in 1769 and 1771.[88][89] Washington was a taciturn legislator uncomfortable with public speaking. Although he served on the Propositions and Grievances Committee and several special committees concerned with military issues, he remained a secondary figure in the House of Burgesses for much of the next decade, and only began to play a significant role in the business of the House in 1767.[90][91][92]

Political awakening

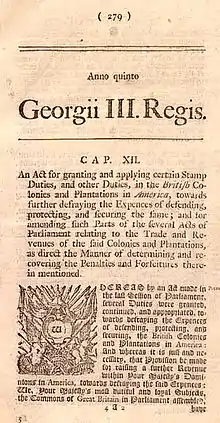

In the aftermath of the French and Indian War, the British sought to impose taxes on the colonies and restrict colonial autonomy. Initially, not all British measures troubled Washington, and some worked to his advantage; the pacification of the Ohio Country by British troops financed by colonial taxes would assist his land speculation interests there. Although he considered the Stamp Act of 1765 an unconstitutional tax that threatened colonial liberties, he believed the British would quickly realize the Act to be a blunder and distanced himself from the reactions of radicals opposed to it. He was busy at Mount Vernon with his efforts to switch from tobacco to wheat when the House of Burgesses voted to pass the Virginia Resolves.[93][94] When the British imposed import duties and asserted their right to levy taxes on the colonies with the Townshend Acts, Washington's initial reaction was muted. He was again absent when the House of Burgesses convened to discuss the Acts in early 1768, having remained at Mount Vernon to meet with William Crawford to review the first surveys of the bounty lands. He reached Williamsburg only after the House adopted a formal remonstrance against the Townshend duties. When London refused to repeal the Acts, several colonies adopted more radical action and boycotted British imports.[95]

Washington's own radicalization began at the end of 1768. By April the next year, having received news that Philadelphia and Annapolis were joining the boycott and that Parliament had proposed to ship ringleaders to Great Britain to stand trial for treason, he was denouncing British policy as a threat to liberty and was one of the first, if not the first, to speak of a resort to arms. He collaborated with George Mason to produce a plan for Virginia to join the boycott.[96][97] On May 16, 1769, the House of Burgesses passed four resolves asserting its sole right to raise taxes, its entitlement and intention to petition the king for the redress of grievances, and that trials for acts of treason committed in Virginia must take place in Virginia. The following day, the royal governor, Lord Botetourt, responded by dissolving the House.[98]

The burgesses reconvened unofficially at the Raleigh Tavern where, on May 18, they formed the Virginia Association, a nonimportation scheme based on the plan Washington had formulated with Mason. In approving it, the burgesses protested "the Grievances and Distresses, with which his Majesty's American subjects are oppressed", but professed their "inviolable and unshaken Fidelity and Loyalty to our most gracious Sovereign." At the close of business, they drank toasts to the king. They saw no contradiction between their assertion of colonial rights and loyalty to the king.[99] But while Mason was looking to coerce the British back to the previous system of harmonious colonial dependency, Washington was beginning to favor a partnership between autonomous North American provinces and Great Britain.[100]

According to Ron Chernow, author of a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Washington,[101] Washington's transformation from a man pursuing self-advancement to a leading figure in the nascent rebellion was the culmination of the frustrations he experienced in his dealings with the British: his failure to secure a royal commission; his disaffection in his dealings with London merchants; and impediments British policy had placed in the way of his business interests.[102] While not entirely dismissing an altruistic libertarian ideology, John E. Ferling argues that Washington's militancy was shaped by his proud and ambitious quest for wealth and recognition, and the obstacles placed in the way of that quest by a British ruling class that regarded the colonies as subservient, their inhabitants second class.[103][lower-alpha 6] Paul K. Longmore argues that in addition to the personal grievances that had accumulated in his career, Washington saw a pattern of oppression that betrayed a British intention to keep the colonies in a state of economic and political servitude. Washington's outspoken support for a nonimportation scheme, Longmore concludes, was based on his belief that such a scheme would promote colonial manufacturing, end American economic dependence on Great Britain and reduce the growing debt of Virginia's ruling classes, a debt that was undermining their moral integrity, social authority and political independence.[104]

Political ascendancy

The situation was defused when London backed down and, except for a tax on tea designed to assert its authority, repealed the Townshend Acts. Other than refusing to serve tea, Washington did not concern himself with the fault lines in British-colonial relations and returned his attention to his business. When he turned forty in 1772, he decided to have his portrait painted for the first time. He commissioned Charles Willson Peale and, despite having resigned his commission 13 years earlier, chose to sit in the uniform of a colonel in the Virginia Regiment.[105][106]

In late 1773 and early 1774, Washington's concerns lay closer to home than the events of the Boston Tea Party protest.[107] Although land west of the Alleghenies had been re-opened for settlement in 1768, British procrastination in establishing a provincial government there suppressed the value of Washington's land in the area; few farmers were interested in leasing land that was not yet subject to civil control and military protection. In 1773, British proponents of the policy to constrain colonies to coastal regions again restricted settlement west of the Alleghenies. While this did not affect land already granted to Washington, it limited future speculation to land granted to veterans of the French and Indian War, by which Washington still stood to gain 10,000 acres (40 km2).[108] When this avenue was closed to him by the decision that only regular army officers qualified for the grants, Washington railed at British malice towards colonists.[109]

.jpg.webp)

Washington's personal interests were further threatened by the Quebec Act of June 1774, designed to abolish Virginia land speculation west of the Alleghenies.[110][111] The Act was part of the Intolerable Acts, the British response to the Boston protests. Among them was the Boston Port Act, passed at the end of March, which closed the port until reparations were made for the lost tea and stationed 3,000 British troops in Boston. Because of his increasing interaction with the politically sophisticated Mason, Washington – who confessed himself not well versed in politics – became fully radicalized over the following months. The occupation of Boston was, he wrote, "unexampled testimoney [sic] of the most despotic system of tyranny that ever was practiced in a free gov[ernmen]t".[61][112][113]

When Governor Dunmore prorogued the House of Burgesses in May 1774 to forestall any resolution supporting Boston, the burgesses gathered unofficially in the Raleigh Tavern. They ratified a boycott of tea, recommended an annual general congress of deputies from all the colonies, and agreed to reconvene on August 1.[114][115][116] To prepare for the next meeting, the burgesses conferred at the county level. Fairfax County adopted the Fairfax Resolves, agreed in a committee chaired by Washington.[117][lower-alpha 7] One resolution proposed a fresh round of nonimportation enforced by extralegal committees, followed by an embargo on exports if nonimportation failed to convince the British to back down. Another resolution adopted a more inflammatory version of the 1765 Virginia Resolves' assertion of colonial rights.[119] The final resolution recommended petitioning the king to assert Virginia's rights and privileges and, with expressions of loyalty to the Crown, warn the king "to reflect, that from our Sovereign there can be but one Appeal." Fairfax County proved to be the most militant county, the only one adopting a resolution that plainly threatened that "one Appeal", the resort to arms.[120]

The First Virginia Convention convened at Williamsburg on August 1, 1774. It agreed the need for a general congress of deputies from all the colonies and a plan of action that conformed closely to the Fairfax Resolves Washington had presented. From a man who dealt little in politics, Washington was emerging as a key political figure in Virginia. He was elected third in the poll for the seven deputies Virginia would send to the First Continental Congress at Philadelphia in September, winning 98 of the 104 votes.[121][122]

Militancy

Washington had despaired of petitions and remonstrances. In favoring more strident measures, he embraced the idea of rebellion and, if necessary, the use of force. He regarded the Intolerable Acts as part of a "regular, systematic plan...to fix the Shackles of Slavry [sic] on us" and believed that Great Britain, in singling out Massachusetts for punitive action, was employing a divide and conquer strategy to subdue the colonies. Washington considered the cause of Massachusetts to be America's cause.[123][124]

Washington's military reputation made him Virginia's candidate for a leading position in the army that would fight a war many believed to be inevitable, but he did not play an active role at the First Continental Congress. Much of the business of the congress was conducted over dinners and informal gatherings outside the formal sessions, during which delegates sized each other up and assessed the appetite for armed conflict. Washington was sought out for his views on the colonies' ability to wage war on Great Britain. In a country with a deep-rooted unease about the overwhelming power an army could wield, he was also being appraised for his trustworthiness as a leader of such an army.[125][126]

Among the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress was the agreement to establish the Continental Association of nonimportation, nonconsumption and nonexportation. It was modeled on the agreement adopted by Virginia, itself based on the Fairfax Resolves.[127] The congress also urged the mobilization and training of colonial militias, a measure that was the sole prerogative of the state governors.[128] During Washington's absence, Fairfax County established, without authorization, Virginia's first independent company of volunteer militia. The decision to raise the extralegal force was undoubtedly agreed upon between Washington and Mason before Washington left for Philadelphia, and it was Mason who convened and chaired the meeting that established the company. Washington played a leading role in raising and equipping various county militias on his return from the congress.[129][lower-alpha 8]

Fairfax County cemented its position as the most militant county in Virginia when Washington, Mason and others recommended the expansion of the militia with all able-bodied freemen aged between 18 and 50 and the levying of a tax to finance it.[131] News that Washington was playing a leading role in preparing for war reached as far as London, and in Virginia and Pennsylvania his name was being linked to a leading position in a continental army.[132] At the Second Virginia Convention, convened in March 1775, Washington sat on two committees responsible for the raising and supply of troops to place the whole of Virginia into a "posture of Defence." The convention also elected delegates to represent Virginia at the Second Continental Congress scheduled for May. Washington moved up a place in the poll, chosen second behind Speaker Peyton Randolph.[133]

General Washington

Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which began the American Revolutionary War in April 1775, the four militia armies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New Hampshire laid siege to the British in Boston. Although there was a tacit agreement that General Artemas Ward, commander of the Massachusetts militia, was commander-in-chief of the operation, the colonial armies took their orders from their provincial assemblies.[134][lower-alpha 9] A priority of the Second Continental Congress – which oversaw the war effort until 1781 when the Articles of Confederation established the near powerless Congress of the Confederation – was to establish a unified army under central control.[136][137][138] Washington, who advertised his military credentials by attending Congress in uniform,[139] played a leading role in the military planning. He chaired four committees organized to counsel New York on its defensive preparations, draft plans for an intercolonial system of supply, discuss the financial arrangements for a twelve-month campaign and draft rules and regulations for the forces.[140] On June 14, Congress voted to establish the Continental Army. The following day it unanimously voted to appoint Washington commander-in-chief.[141] He refused a salary, saying he would accept only the reimbursement of his expenses.[142]

Republican

In sitting through the sessions of the Second Continental Congress in a uniform he had designed, Washington was presenting himself as gentleman commander of militia volunteers. When the New York Provincial Congress expressed a widespread distrust of professional standing armies and the fear that he would abuse his position to become a dictator after the war, Washington replied, "When we assumed the Soldier, we did not lay aside the Citizen, & we shall most sincerely rejoice with you in that happy Hour, when the Establishment of American Liberty...shall enable us to return to our private Stations..."[143] Shortly after arriving outside Boston, he wrote to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress of his intention to sacrifice "all the Comforts of social and political Life, in Support of the Rights of Mankind, & the Welfare of our common Country."[144]

A month after taking command, Washington wrote to Lieutenant General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces, to protest the treatment of prisoners held by the British. Gage refused to recognize any rank not derived from the king and declared the prisoners to be traitors "destined to the Cord". To the British general's accusation that he was acting with usurped authority, Washington replied that he could not "conceive any more honourable [sic], than that which flows from the uncorrupted Choice of a brave and free People – The purest Source & original Fountain of all Power."[145] For many activists, what had begun as a protest against taxes had become a republican uprising. Washington's statements were a manifesto for his behavior throughout the war and demonstrated his commitment to the republican ideals of a military subject to civilian authority, government answering to the wishes of the governed and sacrifice for the greater good. According to Ferling, "For the first time in his life, Washington was truly committed to an ideal that transcended his self-interest...He had become General Washington, the self-denying and unstinting warrior who was focused on the national interest and on victory."[146]

Although Washington deferred to Congress throughout the war,[147] the fear of military despotism never fully receded. It regained momentum after victory at Yorktown in October 1781 when, despite the war having been apparently won, Washington retained the army in a state of readiness for the two years it took to conclude a peace treaty and for British troops to leave American territory.[148][149] In May 1782, Washington unequivocally rejected the Newburgh letter, which voiced many officers' opinion that he should become king,[150] and his defusing of the Newburgh Conspiracy in March 1783, in which officers had threatened to refuse to disband the army after peace, reaffirmed his commitment to the republican principle of a military subservient to the state.[151]

Nationalist

Washington's experiences in the French and Indian War had revealed the danger of competition among the colonies.[63] In his first year commanding the Continental Army, he revealed his former loyalty to Virginia had now become an allegiance to America. His desire to standardize the uniform of the army demonstrated his intention to abolish provincial distinctions. He avoided any appearance of partiality towards fellow Virginians and sought to transfer the right to appoint officers from the provincial governments to Congress. His growing nationalism was reflected in his shifting use of the word country to mean America rather than individual provinces.[152]

In 1776, Washington refused to accept two letters sent by the new British commander, General William Howe, because they were addressed to "George Washington Esq." In insisting that he be addressed by his rank, he was rejecting the British premise that the revolutionaries were simply rebellious subjects. A British emissary gained access to Washington by addressing him as General, but when the emissary tried to deliver the second letter again, Washington again refused it. The episode demonstrated that Washington commanded the army of a nation.[153] He believed the revolution to be a struggle not just to establish colonial independence from Great Britain but also to unite those colonies to form an American nation.[154]

Independent

.jpg.webp)

In October 1775, Washington conferred with a congressional committee on the reorganization of the army. Among the measures adopted on his recommendation was the death penalty for acts of espionage, mutiny and sedition. The imposition of capital punishment was an implicit act of sovereignty by an independent nation. Washington, having once served in the French and Indian War without pay out of a "laudable desire" to serve "my King & Country", was now leading the revolution away from what was still, at this point, a struggle to redress grievances and towards a war of independence.[155][156] Throughout the crisis, the revolutionaries had made a distinction between Parliament and King George III. It was the king's ministers who had deceived the king and sought to oppress the colonies, and it was the king on whom the revolutionaries pinned their hopes for redress.[157] Even as Congress discussed the establishment of the Continental Army, a majority supported petitioning the king to restore relations by rebuking Parliament.[139]

Although Washington had come to doubt the king's willingness to support the colonial cause as early as February 1775, until November he remained careful to maintain the distinction between ministry and king; in his exchange with Gage, who as an officer in the British Army was acting on the commission of the king, he had pointedly referred to "those Ministers" under whom Gage acted.[158] The king's spell over the revolutionaries was finally broken in October 1775 after he had made clear his view that they were in open revolt aimed at independence and his determination to put that revolt down by force. The revolutionaries began to heap on King George III all the charges they had previously laid at the door of his ministry. As the colonies moved towards the Declaration of Independence the next year, Washington's nationalism intensified. He began to explicitly refer to his enemy not as ministerial troops but the king's troops, and he took a harder line against Loyalists, directing that they be disarmed and supporting their detention as traitors.[159]

Political infighter

Washington's failure to prevent the British from occupying New York at the end of 1776 and Philadelphia in September 1777, along with his conduct of the war,[lower-alpha 10] led to criticism within Congress and his own officer corps about his abilities as commander-in-chief.[161] By November 1777, he was hearing rumors of a "Strong Faction" within Congress that favored his replacement by General Horatio Gates, who had won major victories in September and October at the Battles of Saratoga.[162] Washington felt the appointment of General Thomas Conway, an Irish-born Frenchman known to be a critic, as inspector general of the Army to be a rebuke. Washington was troubled too by the appointment of three of his detractors to the congressional Board of War and Ordnance – among them Thomas Mifflin and Gates, who served as the board's president. Washington became convinced there was a conspiracy to take command of the army from him.[163][lower-alpha 11]

In January 1778, Washington moved to eliminate the "malignant faction".[165] Publicly, he presented an image of disinterest, a man without guile or ambition. He told Congress his position made it impossible for him to respond to his critics. He did not deny the rumor that he was contemplating resignation, stating only that he would step down if the public wished it. Washington knew that his friends in the army would be more vocal on his behalf, and on occasion they did not shy away from intimidation.[166][167][lower-alpha 12] Washington's supporters in Congress confronted congressmen suspected of having doubts about Washington, leaving John Jay feeling that openly criticizing Washington was too risky. In February 1778, four months after Mifflin resigned as quartermaster general, Congress began auditing his books. The inquiry was not concluded for nearly fourteen months, though no charges were laid.[169] A plan proposed by, among others, Gates and Mifflin to invade Canada, one in which Conway was to have a leading role, was depicted by Washington's supporters in Congress as part of the intrigue against Washington, more political than military in its conception, and was eventually dropped.[170] Washington refused to appoint Gates to a command in Rhode Island that might have allowed Gates to eclipse Washington with another victory, nor would he countenance a later proposal by Gates for an invasion of Canada which Gates was to lead.[171] He engineered Conway's resignation by using the Frenchman's own acerbic manner and contempt for American soldiery to turn Congress against him.[172][lower-alpha 13]

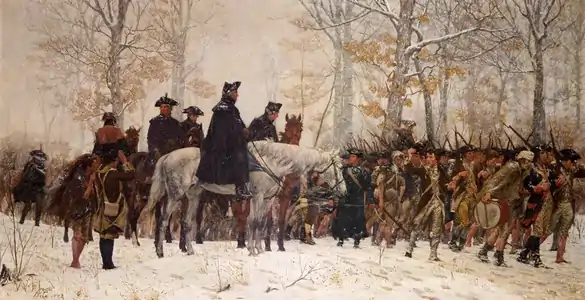

Indispensable revolutionary

Having seen his army dissolve as short-term enlistments expired towards the end of 1775, Washington convinced Congress after the loss of New York to establish a permanent standing army recruited with men who enlisted for the duration.[174] For all his military failures, Washington's reticence to risk that army in a pitched battle and his skill in keeping it from dissolution over the difficult winter of 1777–1778 at Valley Forge – a winter in which food was always in short supply and deaths from disease accounted for 15 percent of its strength – ensured there was still an army that could take the field when France entered the war as an ally early in 1778. Washington was the glue that kept the army together, the hope of victory and independence alive. With his clever campaign of political infighting having largely silenced his critics, Washington's position became unassailable. He emerged in 1778 as a truly heroic figure, the "Center of our Union", and was lauded for the first time as "Father of his Country".[175]

Federalist

The inability of Congress to compel the states to raise troops or provide for them convinced Washington of the need for a strong federal government. In 1777 Washington began sending circulars to the states to request the resources he needed to fight the war, but the Continental Army came close to dissolution and starvation several times because they failed to adequately support the war effort. By 1780, Washington believed the war would be lost unless the states ceded to Congress greater power to prosecute it.[176][177] Following the Newburgh Conspiracy in 1783, he weighed in on the debate to amend the Articles of Confederation to give Congress the power to raise taxes to pay the army, and spoke for the first time to a national audience in support of a more powerful central government.[178]

Two of the three great state papers Washington produced were written in 1783 about union.[179] The first, Sentiments on a Peace Establishment, advocated a peacetime standing army and state militias subject to standards of organization and training set by national law. In the Circular to the States he argued for a strong national government, writing that there must be "a Supreme power to regulate and govern the general concerns of the Confederated Republic" and that unless "the States...delegate a larger proportion of Power to Congress...the Union cannot be of long duration."[180] To allay fears that he was promoting his own career, Washington repeatedly pledged to retire from public life.[181][182] In his farewell address to the army he wrote again of the need for a strong national government, and at a dinner given by Congress in his honor in December his toast was "Competent powers to congress for general purposes."[183] The regional reputation Washington had won became national, international even,[184] and the lasting fame he sought was inextricably linked to the survival of the Union.[185] He also believed union under a strong central government was necessary to open the West and prevent a divided America from becoming the "sport of European politics."[186]

President Washington

Washington resigned his commission on December 23, 1783. His relinquishing of power laid to rest any fear that he would use the army to assert political power and perpetuate, as Thomas Jefferson later wrote, "a subversion of that liberty it was intended to establish."[187][188] To Joseph Ellis, the act revealed Washington's mastery of his ambition, his understanding that by surrendering power he was enhancing his reputation, and demonstrated his commitment to republicanism.[189]

Garry Wills describes Washington's resignation as "pedagogical theater".[190] It was, Wills argues, designed to give moral force to the arguments Washington made in the Circular to the States for a strong national government. Washington had seen the continental identity that had been forged in the army and how that unity had led to a successful resolution of the military situation. He saw in the new republic's post-war political situation the next crisis and hoped – vainly as it turned out – that the political capital he had built up and then magnified with his resignation would encourage the same unity of government.[191]

Washington returned to Mount Vernon, delighted to be "free of the bustle of a camp & the busy scenes of public life." From a family in which a father and three brothers had died before reaching fifty, he would soon be celebrating his fifty-second birthday.[192][193] He professed a desire to spend his remaining days peacefully and quietly, "basking" in adulation according to Ferling, "enduring" it according to Chernow. One of the first American celebrities, Washington was fêted during a visit to Fredericksburg in February 1784 and received a constant stream of visitors wishing to pay homage to him at Mount Vernon.[194][195] Public matters were never fully out of his mind, and he wished to be seen, as a Georgia public official put it in 1787, as a "politician and States-man" who was always "virtuous and useful".[196][197] But, believing he was coming to the end of his life and that his public career was over, he focused his attention on his business interests.[198]

Within a year of returning to Mount Vernon Washington had reached the conclusion that the Articles of Confederation had to be overhauled,[199] but felt that public opinion was not yet ready to accept a strong central government until some crisis made it clear such a government was necessary.[200][201] He did not attend the Annapolis Convention, convened in September 1786 to agree to the regulation of commerce throughout the thirteen states. Only five states sent delegates, and the only agreement reached was to schedule another convention in Philadelphia for the following May. The Constitutional Convention was to go beyond commerce and produce a plan designed to strengthen the federal government by amending the Articles of Confederation. Nationalists regarded Washington's support to be vital; his presence would encourage delegates from all states to attend and give weight to whatever proposals the convention came up with.[202]

Constitutional Convention

Late in 1786, the Virginia legislature nominated Washington to head its seven-man delegation to the convention. This presented him with a number of problems. He had previously declined to attend a meeting of the Society of the Cincinnati, also scheduled for May in Philadelphia, with polite excuses that masked his discomfort at being associated with an organization increasingly seen as incompatible with republican principles. To attend the Constitutional Convention would have caught him in an embarrassing lie.[203][lower-alpha 14] He was anxious not to be associated with anything that might damage his reputation and feared the convention would be a fiasco if, as at Annapolis, several states did not send delegates.[205][206] He was concerned about the strength of opposition to a convention that might erode state autonomy, and that, because amendments to the Articles of Confederation could only originate in Congress, the convention was not legal.[205][207] Washington was also concerned his attendance would be perceived as inconsistent with the declaration he had made in 1783 to retire from public life.[208]

When Washington formally declined the nomination on December 21, James Madison requested he keep his options open, and Washington's name remained on the list of delegates "contrary to my desire and...request."[209] As nationalists appealed to him to attend, Washington canvassed his friends for advice.[210][211] The question of legality was settled on February 21, 1787, when Congress sanctioned the convention "for the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation."[212] Washington was swayed by the events of Shays' Rebellion, which he saw as the crisis that would galvanize public opinion in favor of change. He was also convinced by Madison and Henry Knox that the convention would carry enough weight and have enough chance of success to be worth risking his reputation for.[210][213] On March 28, Washington formally accepted the nomination. He resolved his dilemma with the Cincinnati by agreeing to address the society immediately before the convention convened.[214]

For four months, Washington presided over a convention that went beyond its remit to amend the Articles of Confederation and thrashed out a new constitution, but contributed little himself.[215] He was happy with the proposal eventually agreed, a constitution designed to create a new national government nearly as powerful as the one only recently overthrown. Supporters of the new constitution leaned on his name heavily in their nine-month campaign to convince the states to ratify it, while he himself played an occasional, covert role in support, going so far as to self-confessedly meddle in Maryland's ratification process.[216][217]

Presidency

After the adoption of the new constitution was assured in June 1788, appeals mounted for Washington to accept the presidency, but it was not until January 1789 that he did so. He was formally elected in April, becoming the first president of the United States and the only president to be elected unanimously.[218][219] His inaugural address gave little insight into his political agenda which, from private correspondence, appears to have comprised two priorities: restoring fiscal responsibility and establishing credibility for the new national government.[220]

Washington hoped to serve only two years, enough time to steer the new government towards stability then retire, but he served the full four-year term. He presided over an administration that became increasingly partisan as Alexander Hamilton battled Madison and Jefferson to set the direction of the new republic.[221][222] In the last year of his first term, he spoke often of retiring. He had reached sixty and his health was declining. He told friends that he did not enjoy being president, and spoke of his concern that to serve another term might invite accusations of a lust for power.[223] It was the fear that the union would unravel in sectional tensions without him and the threat the French Revolutionary Wars posed to American unity, security and prosperity that convinced Washington to assent to a second term.[224][225]

Washington's second term saw the entrenchment of politics into the Federalist Party and Democratic-Republican Party.[226] His attempts to ensure American neutrality in the French Revolutionary Wars generated unprecedented levels of criticism. After signing the Jay Treaty with Great Britain, a treaty which conferred few advantages on America, Washington was castigated in the Democratic-Republican press as a "tyrannical monster" who favored "the greatest good of the least number possessing the greatest wealth." Thomas Paine, in his 1796 Letter to George Washington, attacked the president's monarchical style in office, accused him of betraying the ideals of the revolution and siding with the Federalists to emulate British-style authority, and denigrated his record in the Revolutionary War.[227]

Farewell to politics

Advancing years, declining health and the attacks of the press ensured Washington's second term would be his last. His final days as president were a whirlwind of social engagements at which he basked in the acclaim of his achievements, though some Democratic-Republicans toasted "George Washington – down to the year 1787, and no further."[228] His final address to Congress called for an expanded federal mandate and betrayed a Federalist bent that contradicted his efforts during his presidency to portray himself as non-partisan.[229] The major point in his farewell address was his belief that a capable federal government was the proper fulfillment of the American Revolution and the means by which American independence would endure.[230] In March 1797, Washington retired once again to Mount Vernon and busied himself with his businesses. He served one last time in public office, as commander of the Provisional Army formed alongside the existing army in 1798 amid fears of a French invasion.[231] He died at Mount Vernon on December 14, 1799.[232]

Legacy

Washington was eulogized after his death as a man who "took on authority only when his countrymen asked him to do so", "wielded 'power without ambition'" and was "a patriot devoid of personal ambition".[233] Gordon S. Wood concludes that Washington's resignation as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army was "the greatest act of his life, the one that gave him his greatest fame." It was an act that earned Washington widespread acclaim and a place in history as the Cincinnatus of the west, a reference to Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the Roman military leader who, according to legend, relinquished power and returned to his farm after defeating Rome's enemies in the 5th century BC.[182] Washington knew the legend of Cincinnatus,[234] and Wills suggests that he consciously promoted the analogy.[235] Washington's relinquishing of power, Wood writes, played to an image of a man disinterested in politics.[236] Ferling argues that, far from being disinterested, Washington was such a consummate politician that "he alone of all of America's public officials in the past two centuries succeeded in convincing others that he was not a politician."[237]

Ambition

According to Longmore, Washington's ambition for distinction spun inside him like a dynamo throughout his life.[238] Ferling characterizes Washington's ambition not only as an obsession with his own advancement in renown, power, wealth and success, but also ambition for his country.[239][240] Peter R. Henriques, professor of history emeritus at George Mason University and member of the Mount Vernon committee of George Washington Scholars,[241] writes of Washington's profound ambition for honor and glory.[242] John Rhodehamel, former archivist at Mount Vernon and curator of American historical manuscripts at the Huntington Library,[243] echoes the theme of honor and places Washington's ambition in the context of contemporary mores, writing, "...George Washington's ambition became that noble aspiration that was so distinctive of his age. Like his great contemporaries, Washington came to desire above all else the kind of fame that meant a lasting reputation as a man of honor."[244]

Ferling describes Washington as "mad for glory" in the French and Indian War, and concludes that the attack on Jumonville was motivated by Washington's desire to prove his courage and acquire the fame he hungered for.[245] According to some accounts, Washington continued his advance on the Forks after the battle.[lower-alpha 15] This was a recklessness which, according to Longmore, was driven in part by a concern that Washington would be unable to win further acclaim once Colonel James Innes, who had been appointed commander-in-chief of all forces, arrived and took over command.[33][lower-alpha 16]

Washington's ambition for honor and reputation weighed heavily in his decision to accept the appointment as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. The position gave him further opportunity for military glory and public recognition, and his "yearning for esteem", Longmore writes, "became a quest for historical immortality."[251] Ferling ascribes Washington's personal motives to a keen sense of history. Washington had shown the legacy he wanted to leave when he posed for Peale's portrait in the uniform he had last worn 13 years previously; command of the Continental Army allowed him to win further acclaim for a greater cause on a grander stage.[252]

Wood argues Washington took care throughout his life to mask his ambition with an image of disinterestedness and was obsessively concerned not to appear "base, mean, avaricious, or unduly ambitious."[253] Such a stance was, according to Ellis, common in an era when openly seeking office indicated a failure to control ambition and therefore betrayed someone as unworthy of holding office.[254] Chernow draws attention to the "canny political style" revealed in Washington's instructions to his brother John when he was first considering election to the House of Burgesses in 1755. They showed Washington's belief that "ambitious men should hide their true selves, retreat into silence, and not tip people off to their ambition."[255] Ferling speculates Washington's concern not to be seen as someone who lusted after power played a part in his hesitation to attend the Constitutional Convention in 1787, a convention that would create the position of president he knew he would be asked to occupy.[205] Ellis believes that, from the time of his appointment to command the Continental Army, Washington had difficulty acknowledging his ambition and needed to convince himself that he had been summoned to public duty "from outside rather than inside his own soul."[256]

Reputation

Having secured a reputation in the French and Indian War, it was important for Washington to protect "what at present constitutes the chief part of my happiness, i.e. the esteem and notice the Country has been pleased to honour [sic] me with."[257] On the night of his appointment to commander-in-chief, he told Patrick Henry, "From the day I enter upon the command of the American armies, I date my fall, and the ruin of my reputation."[258] According to Wood, "Many of his actions after 1783 can be understood only in terms of this deep concern for his reputation as a virtuous leader."[253]

Washington took a keen interest in how he would be remembered by posterity. Having already arranged to have his Revolutionary War papers transcribed, he had them delivered to Mount Vernon in 1783.[259] In 1787, Washington invited his former aide David Humphreys to take up residence at Mount Vernon and write an official biography. Choosing and hosting Humphreys allowed Washington to manage the work of a loyal follower; Washington read and corrected the first draft to produce a revisionist history of his actions during the French and Indian War in which his failures were whitewashed.[260][261] Washington distorted history in his favor when he wrote a letter he knew would be published about his decisions leading to the victory at Yorktown. He disingenuously blamed Congress for the disastrous decision to defend Fort Washington in a letter to the author of a history of the Revolutionary War.[262]

The desire to protect his reputation played a part in Washington's eventual decision to attend the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Nine days before accepting, he had conceded to Knox his concern that his absence would be perceived as dereliction to republicanism and consequently damage his reputation. In response, Knox said that Washington was certain to be elected president of the convention and that, while an imperfect result might damage his reputation to a degree, a successful outcome would "doubly entitle you to the glorious republican epithet 'The Father of Your Country'."[263] The same concern to protect his reputation was a factor in Washington's decision to serve a second presidential term despite his ardent desire to retire.[264]

Political disinterest

After his reelection to the House of Burgesses in 1761, Washington told a visitor, "I deal little in politics."[265] It was, according to Longmore, a reflection of the contemporary moral code that demanded a show of political disinterest, and the genesis of the myth that Washington was a reluctant politician.[266] Washington had begun his career by actively soliciting the positions of militia district adjutant, special envoy and lieutenant colonel in the Virginia Regiment. He adopted a slightly different style in securing a position on Braddock's staff, making an initial approach then allowing his friends to promote his cause. His subsequent appointments were characterized by protestations of inadequacy and reluctance before finally assenting at the entreaty of others. This approach was apparent in 1755, when Washington declined to actively seek appointment to the command of the Virginia Regiment.[44] He wrote to one friend, "...I am unequal to the Task...it requires more experience than I am master of...".[267][268] To another, he confessed that he was interested in the appointment, but would not solicit it, preferring instead that it should be offered to him.[45][269] To his mother, he wrote that it would be dishonorable to refuse "if the command is pressed upon me, by the general voice of the country."[45][270]

According to Longmore, this was a technique that allowed Washington to increase his influence and authority, one he would employ in "more sophisticated and subtle performances" leading to his selection for high office in the Continental Army, at the Constitutional Convention and two terms as president.[267] Chernow writes that Washington's appointment to command the regiment "banished any appearance of an unseemly rush to power", and that Washington's decision not to campaign in person for election to the House of Burgesses in 1758 was in part because he had "begun to intuit the subtle art of seeking power by refraining from too obvious a show of ambition."[271]

Washington did not directly solicit the job of commander-in-chief in 1775 and repeatedly claimed it was a position he neither sought nor desired, one that he accepted only after "much entreaty."[272][273][274][lower-alpha 17] His appointment, according to Chernow, demonstrated the "hallmark of Washington’s career...he didn’t seek power but let it come to him...By 1775 he had a fine sense of power — how to gain it, how to keep it, how to wield it."[273] Ferling writes that Washington "crafted a persona" as a noble and disinterested patriot.[281] According to Longmore, Washington's protestations and his refusal of a salary were rooted in a Country Party ideology which emphasised self-sacrifice and public virtue as the best defenses against abuse of power; only men of independent wealth who lacked ambition could be trusted not to be corrupted by power. By cultivating such an image, Washington presented himself as the ideal candidate for a position he wanted.[282]

The same pattern is evident with Washington's selection as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. When he was inaugurated two years later, Washington wrote that his nomination to the convention was "in opposition to my express desire...Never was my embarrassment or hesitation more extreme or distressing."[283][284] When Washington finally accepted the nomination, he stated he was doing so involuntarily and at the entreaties of his friends. His hesitation, according to Chernow, allowed Washington to make it "seem that he was being reluctantly borne along by fate, friends, or historical necessity" and thus "cast himself into the modest role of someone answering the summons of history."[285] But Chernow also lists Washington's concern that the convention would initiate a chain of events that would pull him away from Mount Vernon as a possible reason for his hesitation to attend.[209] Ellis argues that Washington's decision to attend the convention was the grudging and tortured process of an old soldier who relished his retirement as the American Cincinnatus.[286]

In finally accepting the presidency in 1789, Washington again "preferred to be drawn reluctantly from private life by the irresistible summons of public service" according to Chernow,[287] while publicly stating that public life had "no enticing charms" for him and repeatedly expressing a preference to live out his days at Mount Vernon. Although Ferling does not regard Washington's protestation of reluctance to be entirely without truth, it was, he writes, "largely theater", designed to increase his political authority by presenting an image of someone who harbored no personal interest and was only answering his country's call.[288] Henriques reaches a different conclusion and writes that the ageing Washington was genuinely reluctant to take up the presidency. The position could only weaken the fame and reputation Washington had won, but he could not ignore the public esteem he would garner by accepting the call of duty, nor risk damaging his reputation by refusing it.[289][290][lower-alpha 18] Ellis points to Washington's words on the eve of his inauguration, when Washington wrote that he felt like "a culprit who is going to the place of his execution", and writes that Washington "had done everything humanly possible to avoid [the presidency], but that he was, once again, the chosen instrument of history."[291]

Footnotes

- Colonial Virginia was a royal colony. It was governed by a bicameral legislature comprising a royally appointed governor and council, in whom most of the authority was vested, and a popularly elected House of Burgesses.[4]

- In the articles of surrender signed after the Battle of Fort Necessity, Washington had admitted to the assassination of Joseph Coulon de Jumonville at the Battle of Jumonville Glen who, the French claimed, was on a diplomatic mission. The articles of surrender were, according to John Huske, a former Boston merchant and future British Member of Parliament[28][29] "the most infamous a British subject ever put his hand to."[30][31] Washington claimed he would never have knowingly consented to an admission of assassination. He alleged his translator, Jacob Van Braam, had a poor grasp of English and implied that Van Braam acted treacherously to mistranslate the word "assassination" to "death" or "loss".[30][31][32]

- The route to be taken by Forbes to Fort Duquesne would generate economic advantages for landowners along that route. Virginians advocated for the existing route cleared by Washington and used by Braddock, while Pennsylvanians advocated for a new, more northerly route through their territory. Washington argued in support of the Virginian cause on the basis that the new route could not be completed before winter, but Forbes suspected him of acting in his own financial and political interests and chose, for military considerations, to take the Pennsylvanian route.[57]

- Washington had leased Mount Vernon from his brother's widow in December 1754 and inherited it on her death in 1761.[66]

- In his petition to the Executive Council and Virginia's new governor, Lord Botetourt in 1769, to make good the promise of land bounty, Washington suggested two hundred thousand acres (eight hundred and ten square kilometres) along the Monongahela and Kanawha rivers. Given that the surveyor for Augusta County, in which the land was located, would be too busy, he suggested someone else should be appointed to complete the surveys. When his suggestions were agreed, he successfully urged the appointment of William Crawford as the surveyor, whom two years previously Washington had commissioned to conduct a surreptitious survey of the land now allocated. Washington then accompanied Crawford on the initial exploratory trip in 1770 and took notes on the best land. As Crawford completed his surveys, he consulted with Washington, without the knowledge of any other officers, before the results were presented to the Executive Council. Washington then met with the officers, who were assured that there was no difference in quality between the various tracts, to agree how the land would be distributed. The Executive Council then allocated specific grants of land based on their recommendations. In this way, eighteen officers secured for themselves seven-eighths of the bounty lands that Dinwiddie had originally intended solely for enlisted men, men who had not been consulted throughout the process, and Washington secured for himself the best land. Some enlisted men complained when they discovered their land was worthless; some of the officers were a "good deal chagrined" when they first saw theirs.[80] Washington defended his actions by saying there would have been no grants of land without his initiative and effort.[81][82]

- Ferling, like Chernow, cites Washington's frustration at the British military system that subordinated him to men of inferior rank. He also discusses the indignities Washington must have felt in the treatment he received from British officials such as Loudoun; the fact that Virginia's security during the French and Indian War had been dictated by British strategy, not Virginian; that London, not the colonies, controlled Indian diplomacy; that the Ohio Country was opened for settlement on British terms to a British timescale for the benefit of British interests; and that Parliament made all the imperial trade rules for the colonies, while the colonists had no representation and no say in British policy.[103]

- Historians differ as to the role Washington played in formulating the resolves; some credit Mason as the sole author while others suggest Washington had collaborated with Mason.[118]

- In addition to leading the Fairfax militia, Washington accepted command of the Prince William, Fauquier, Richmond and Spotsylvania county militias. He drilled Alexandria's militia, helped the Caroline and possibly Loudoun county militias to get gunpowder, and ordered training manuals, weapons and items of uniform from Philadelphia.[130][128]

- The problems of operating separate provincial armies were manifold and well recognized. The New England provinces did not have the resources to conduct a long-term siege. They considered it unfair that New England should shoulder the main burden of the war effort and believed the conflict should be fought by an army financed, raised and supplied by all provinces. There was some mistrust of a New England army outside of New England. Congressmen attending the Second Continental Congress in May regarded as intolerable the unauthorized march of Massachusetts and Connecticut militias into New York to seize Fort Ticonderoga.[135][136]

- After his defeat in the Battle of Long Island, Washington adopted a Fabian strategy that relied on evasion and hit-and-run attacks to wear down the enemy rather than a decisive pitched battle to defeat it.[160]

- In fact, Congress never contemplated Washington's removal, and the appointments were aimed at reforming the army, not at Washington. Only a tiny minority of congressmen sought his replacement, and he inspired loyalty in an overwhelming majority of his field officers.[164]

- According to Ferling, Washington played the Marquis de Lafayette, who served on his staff and was well connected with the French monarch, "like a virtuoso". Washington hinted to the young Frenchman that, if successful, the cabal's intrigues might destroy the revolution and all that France hoped to achieve from American independence. Lafayette, who only three months previously had praised his good friend and compatriot Conway as an officer who would "justify more and more the esteem of the army", duly condemned Conway to Congress as someone who possessed neither honor nor principles and who would resort to anything to satisfy his ambition. He also belittled Gates's success at Saratoga. Washington's young aides-de-camp, Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens – whose father Henry was President of the Continental Congress – also spoke out against Conway. General Nathanael Greene repeated Washington's accusation that both Mifflin and Gates were intriguing to ruin him. Other officers equated criticism of Washington with treason against the revolution. Suspected critics received visits from officers; Richard Peters was left terrified after a visit from Colonel Daniel Morgan. Conway escaped with a wound to the mouth after a duel with General John Cadwalader; Mifflin lost face when he declined Cadwalader's challenge.[168]

- When Conway arrived to take up his duties at Valley Forge, Washington greeted him icily and informed him he had no authority until written orders arrived. In a written reply, Conway mockingly equated Washington to Frederick the Great, the most esteemed general of the age. Washington simply forwarded the letter to Congress and let outraged indignation at the Frenchman's taunting effrontery to their commander-in-chief run its course.[173]

- The Society of the Cincinnati was a fraternal order of Revolutionary War officers which had attracted suspicion as an aristocratic and politically intrusive organization. Washington's association with the society threatened to sully his reputation. When it refused his attempts to abolish hereditary membership and his request not to elect him president, he sought to distance himself from it by not attending its meetings. Rather than offend his former comrades in arms, he masked his real concerns by stating that he was unable to attend the meeting in May because of business commitments and poor health.[204]

- Rhodehamel writes that after Mackay's arrival, "...Washington began an ill-considered advance from Fort Necessity toward the Forks of the Ohio. He scurried back to Fort Necessity when scouts reported that the French were marching against Great Meadows with a thousand men."[246] According to Longmore, Washington had made the decision to advance before the arrival of the South Carolinians. He moved out of Fort Necessity towards Redstone Creek on June 16 (and may have even entertained hopes of defeating the French at Fort Duquesne alone). By June 28, Washington was still short of the creek but within two days' march of the Forks when he received news that a large French force was approaching. He initially intended to defend the position, but when the South Carolinian contingent caught up with him the next day, Washington and Mackay agreed to fall back, bypassing even Fort Necessity. The whole journey, according to Longmore, took such a toll on the men and their transport that, on reaching Fort Necessity on July 1, they could go no further.[247] According to Ferling, Washington remained at Fort Necessity the entire period between the Battle of Jumonville Glen and the Battle of Fort Necessity.[248] Chernow mentions only that Washington's men were recalled to Fort Necessity on June 28, having been dispersed to build roads.[249]

- In a letter to Dinwiddie after the Battle of Jumonville Glen and following the appointment of Innes, Washington expressed his regret at losing the opportunity to gain more laurels now that "...a Head will soon arrive to whom all Honour [sic] and Glory must be given".[250] The provincial frontier officer William Johnson criticized Washington's aggression and accused him of "being too ambitious of acquiring all the honour [sic], or as much as he could, before the Rest joined him...".[33]

- In a letter to his wife written shortly after his appointment to the command of the Continental Army, Washington wrote, "so far from seeking this appointment, I have used every endeavor in my power to avoid it..."[275][276] In a letter to his brother John Augustine two days later, he wrote that the appointment was "an honor I neither sought after, nor desired..."[277][278] In another letter, written to William Gordon in 1778, he wrote, "I did not solicit the command, but accepted it after much entreaty."[273] His protestations were not limited to private correspondence; the same sentiments are reflected in a public letter he sent to officers of the independent companies of Virginia militia he commanded and published in newspapers.[279] Chernow and Longmore both recognise Washington's protestations of inadequacy were not baseless – where he had previously led a provincial regiment he was now tasked with leading a continental army.[276][280]

- In September 1788, Hamilton advised Washington that a refusal would risk the fame which "must be ...dear to you."[290]

References

- Chernow 2010 pp. 21–22

- Ferling 2009 p. 9

- Chernow 2010 pp. 24–27